Abstract

Like many anthropology museums, the Penn Museum houses the remains of Indigenous ancestors. The Penn Museum’s physical anthropology collection represents an important case study, as its collections are large (encompassing some 10,000 individuals in total), historically significant, and reasonably well documented. These collections also demonstrate many of the complexities of the processes of “objectification” and “museumification” that have long dispossessed Indigenous peoples of their ancestors. The Samuel George Morton cranial collection of approximately 1,600 human skulls amassed in the mid-19th century, is perhaps the most widely known of the Penn Museum’s human remains collections. However, there are others, including hundreds of skulls and other bodily remains from the Penn Museum’s many sponsored archaeological expeditions from the late 19th and through the mid-20th century. These include remains from around the world, with a large percentage from Indigenous peoples of the Americas.

Samuel George Morton began collecting skulls in 1830, leveraging his position as a high-ranking member of the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, America’s first major institutionalized scientific society dedicated to natural history. He relied on a global network of naturalists, physicians, colonial officials, missionaries, military officers, and others to send him skulls. Believing that the size of the skull was indicative of intelligence, he collected skulls to categorize, measure, and rank human races in one of the earliest instances of systematic “scientific racism” in the United States. Morton’s work was used to justify and explain white supremacy, the enslavement of Black people, and the settler-colonial “manifest destiny” of Europeans in the Americas.

Morton published “catalogues” of his collection as it grew, in 1840, 1843, and 1849. Each skull was assigned a number, and Morton usually recorded basic details of each skull’s provenience, along with the name of the supplier—often a grave robber, battlefield scavenger, dissection hall pilferer, or middleman—who sent it to him. Morton also ascribed race, sex, and age at death to the individuals whose remains he catalogued—sometimes relying on details provided by his suppliers, but often based entirely on his own conjectures. Occasionally, the details of an individual’s life history were included or documented in letters that accompanied some of the crania. Morton died in 1851, but his successor, James Aitken Meigs, continued to expand the collection, publishing another “catalogue” in 1857. The Academy of Natural Sciences continued to add to the collection through the 1920s, when the last accession was noted in an unpublished book of accessions.

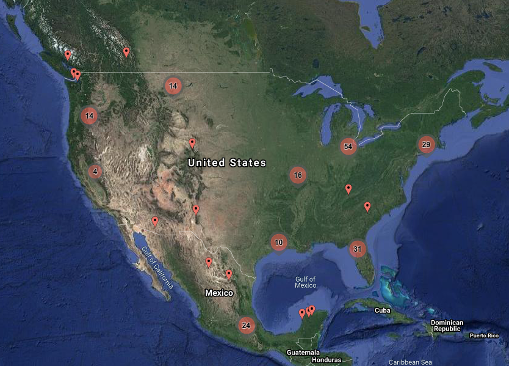

Figure 2. Sites in present-day United States and Mexico from which Indigenous ancestors were collected.

The present mapping of the Morton collection reflects only those remains of Indigenous ancestors from North America that appear in published catalogue records. The mapping plots the approximate provenance—or sites of collection—for these ancestors. Among the 1,035 crania recorded in “the Morton collection” in 1857, 263 belong to Indigenous ancestors in North America. The skulls of white and Black U.S.-Americans, as well as those of enslaved people who died in the Caribbean, are also among the remains that Morton amassed and documented in these catalogues, but they are not included on the map here. (There are also at least seven ancestors from Hawaii that were part of the Morton collection circa 1857 that have likewise been excluded from this mapping.)

The majority of Indigenous ancestors from North America are from what is today the United States, but collectors also took remains from as far north as Baffin Bay and Greenland, and as far south as the Yucatan. Around 80% of ancestors from North America are from the current United States, with most originating from east of the Mississippi River or west of the Rocky Mountains.

The dispossessions of land and bodies in the wake of Andrew Jackson’s “Indian Removal Act” of 1830, and the exploration and colonization of the Oregon Territory—added to the United States in 1846—were among the major, but by no means the only, contexts for these thefts of Indigenous dead. The Mexican-American War of 1846–48 was another significant historical episode that yielded dozens of skulls for Morton.

While these maps offer a broad overview of the sites where these remains were collected, they are not meant to represent the true “origins” of the ancestors in Morton’s collection. This is partly because skull collectors often robbed the graves of ancestors buried far from their homelands as a result of the serial displacements endured by Indigenous people in the Americas throughout the 19th century. Consequently, many ancestors in the collection may have lived and died far from the ancestral and spiritual homelands their communities had inhabited prior to settler intrusion. However, the inaccuracy of the GPS coordinates provided here not only reflects the inherent imprecision of the historical records but also intentionally obscures and protects the exact locations of Indigenous burial sites. The mapping software used here clusters sites together depending on their density and the scale of the map. In order to show all sites between southern Mexico and Greenland, we have provided two separate images of these maps.

We have used general place-markers within defined regions or territories on the map to broadly depict the geographic origins of the Indigenous remains held in the Morton collection and provide historical information about the process of their collection. However, about 10% of the remains catalogued before 1857 lack sufficient documentation to even assign them general place-markers, so they have been omitted from the map entirely. These “unknowns”—which account for 36 of the 263 Indigenous ancestors from North America included in the Morton collection—include remains catalogued under broad, vague labels like “Indian” or “Aboriginal American” without any further information or records associated with them. Although their specific origins are unclear, further research may eventually shed light on their histories.

Given that the datasets used to construct this mapping rely on Morton’s records, we must exercise caution with language used in the further development of this project for two key reasons. First, Morton’s tribal, racial, or ethnic labels were often, at best, second-hand information, and further research may be necessary to verify some of these categories. This is especially important in cases where ancestors were disinterred many years after burial, or where multiple intermediaries were involved before the remains were added to Morton’s collection. Second, Morton often employed settler terms that may not reflect Indigenous names and understandings. Many of these terms and categories represent a distortion of Indigenous history and social life through the imposition of rigid and imprecise taxonomies of settler “science.” In discussing these histories and legacies of dispossession, the question of how to present this information most ethically remains largely a largely open question.