Abstract

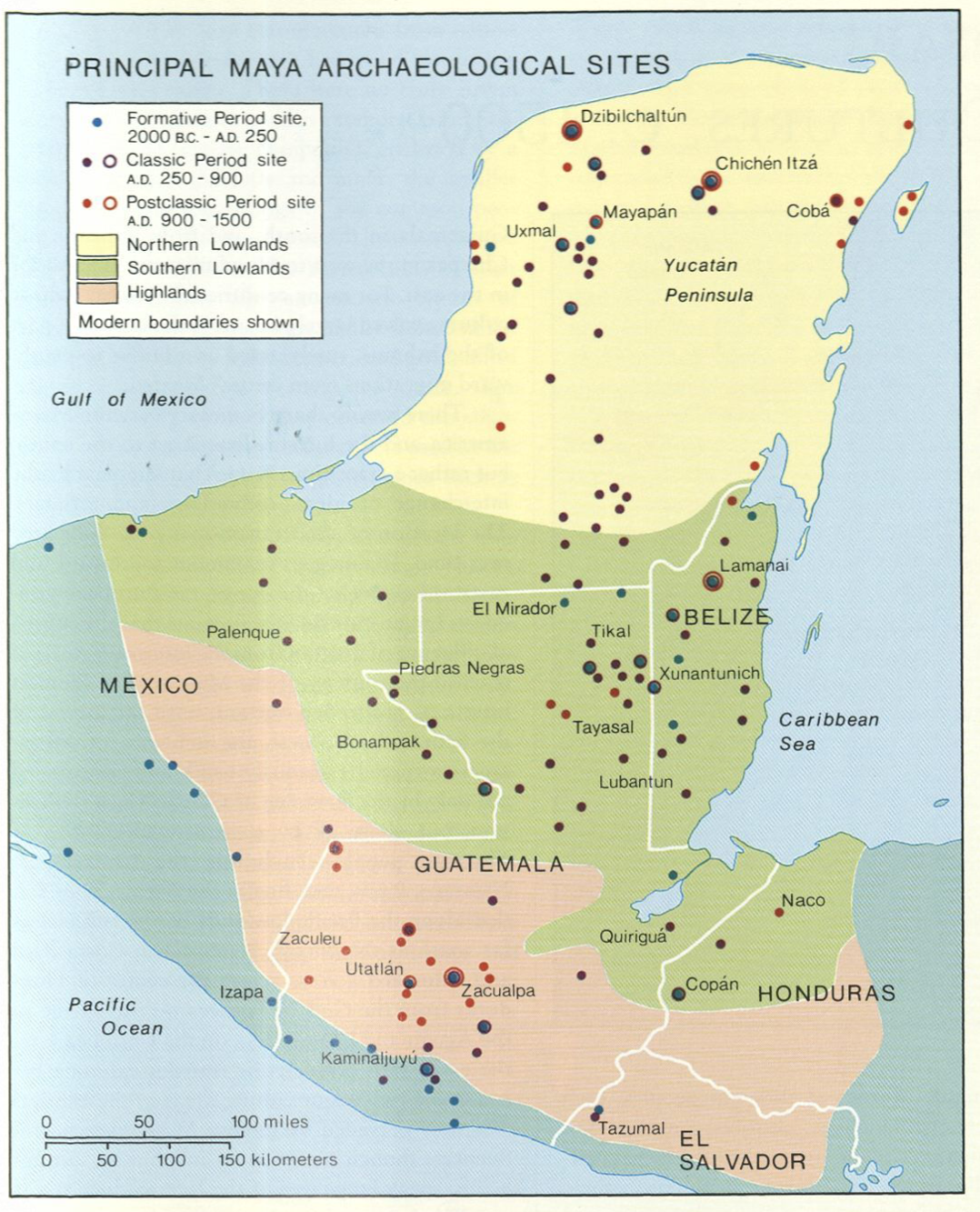

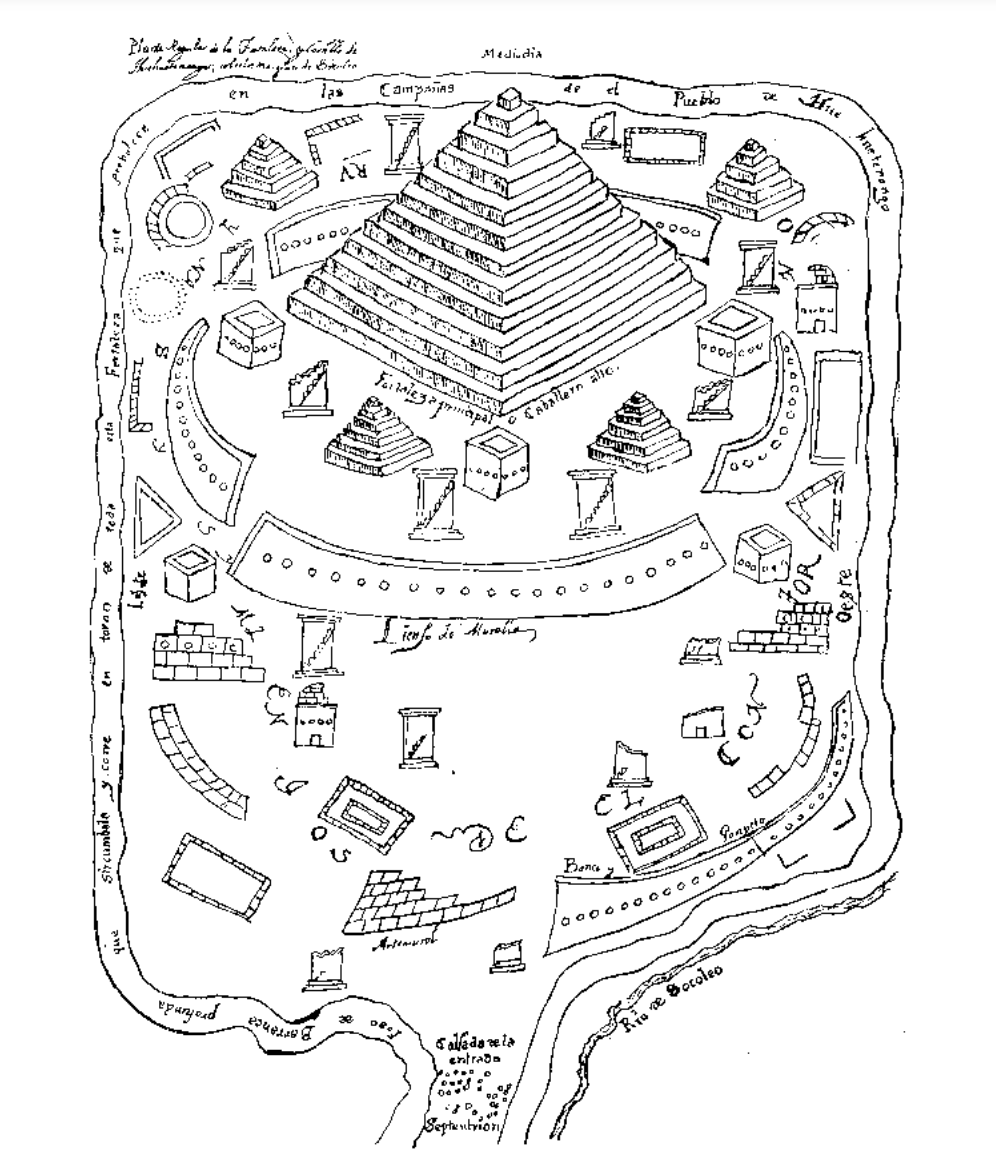

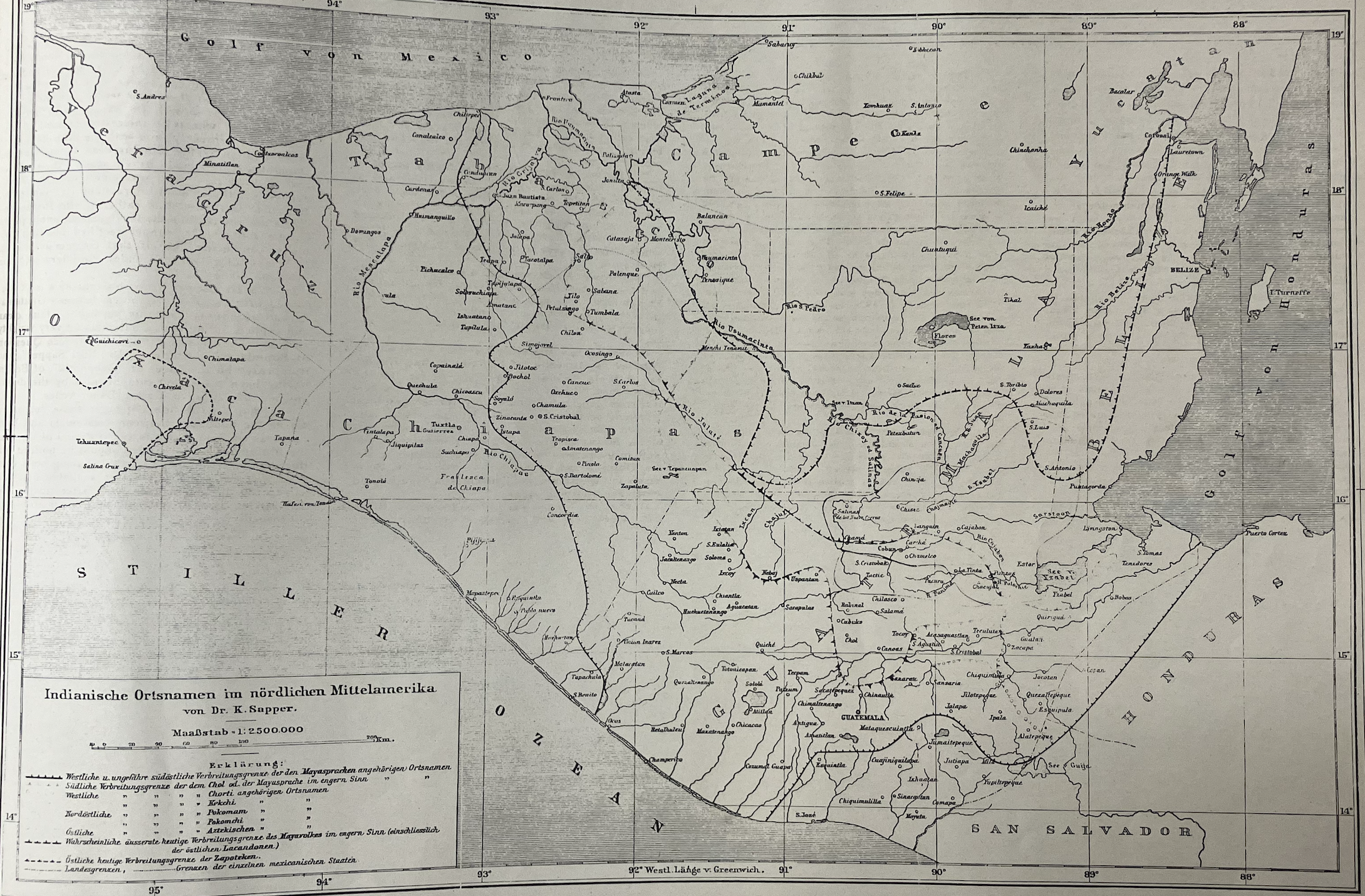

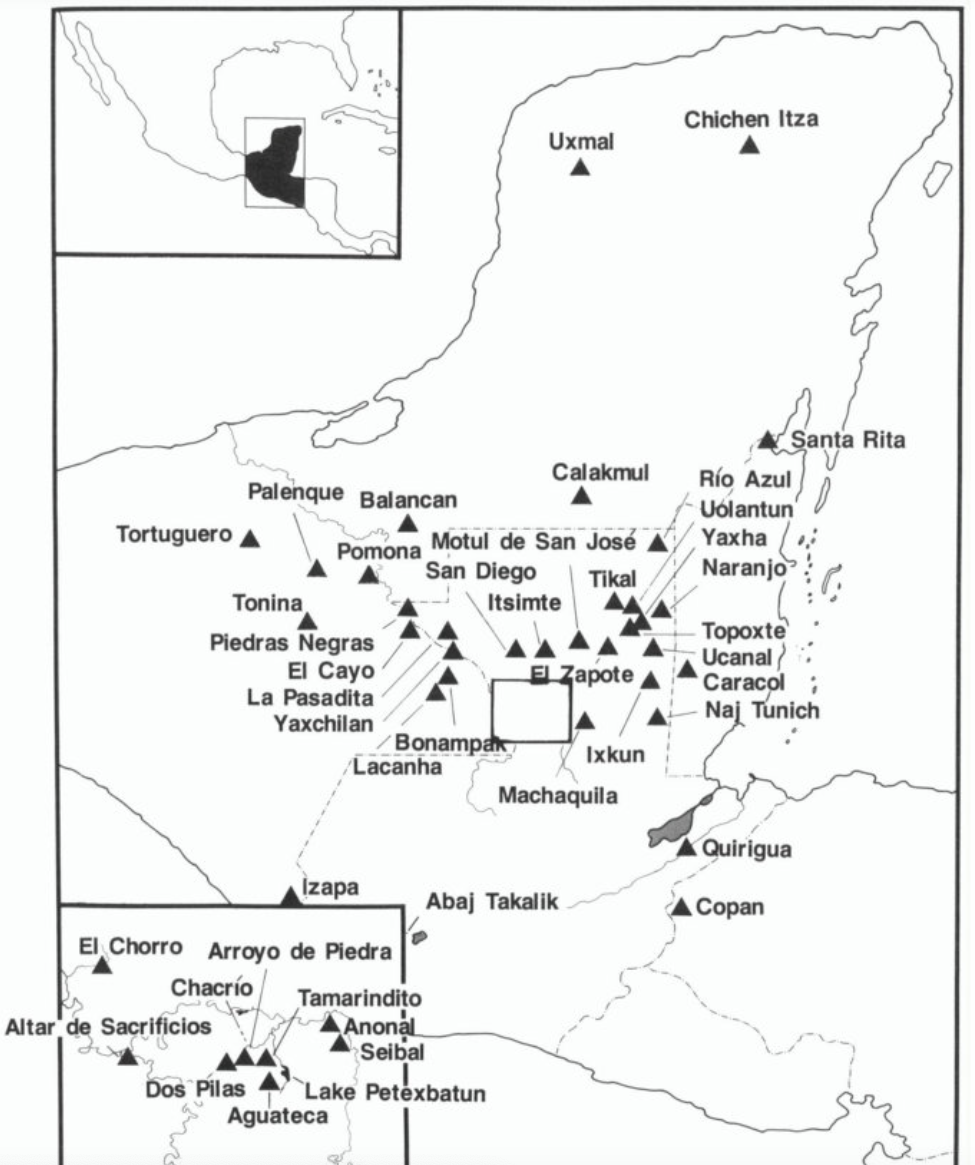

In the 20th century, the United Fruit Company (UFCO) was the largest private landholder in Central America. Notorious for its involvement in uprooting Central American governments to protect its assets, UFCO also upended past ones. By investing in and sometimes outright purchasing archaeological sites, UFCO created quasi-monopolies over ancient and contemporary Maya land and heritage. While many people have researched UFCO’s control of agriculture, few have studied the product of its archaeology. This project shows how UFCO used archaeology to accrue power and territory in Central America in the 20th century.

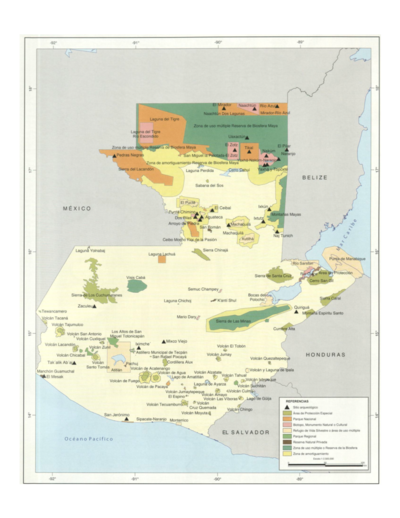

My multi-sited archive research synthesizes archaeological archives with business records, photographs, maps, and video footage to reveal how archaeological sites became quasi-American sovereign zones that funneled antiquities and American researchers through an academic-industrial complex. By UFCO’s logic, land—and its commercialization—was simultaneously valued for potential antiquities and yet threatened by agricultural over-extraction, creating a mechanism for companies to “salvage” sites by nestling and zoning them as protected within their own plantations and infrastructures. While dispossessing Indigenous people of sacred sites and arable land, UFCO positioned itself as an ideal entity to salvage sites from the very threat of its own agriculture, creating ambiguous territorial zones that persist today.