Abstract

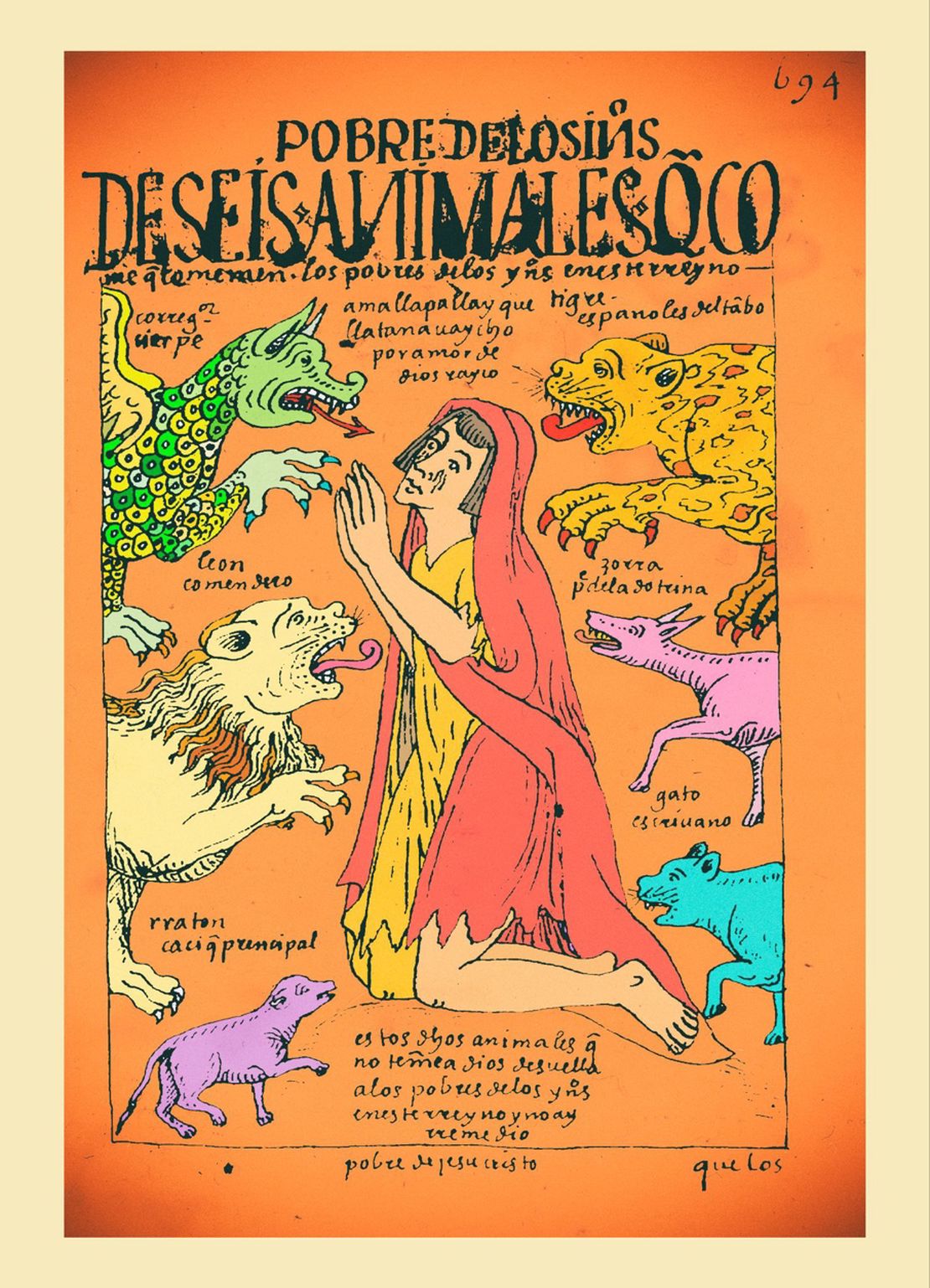

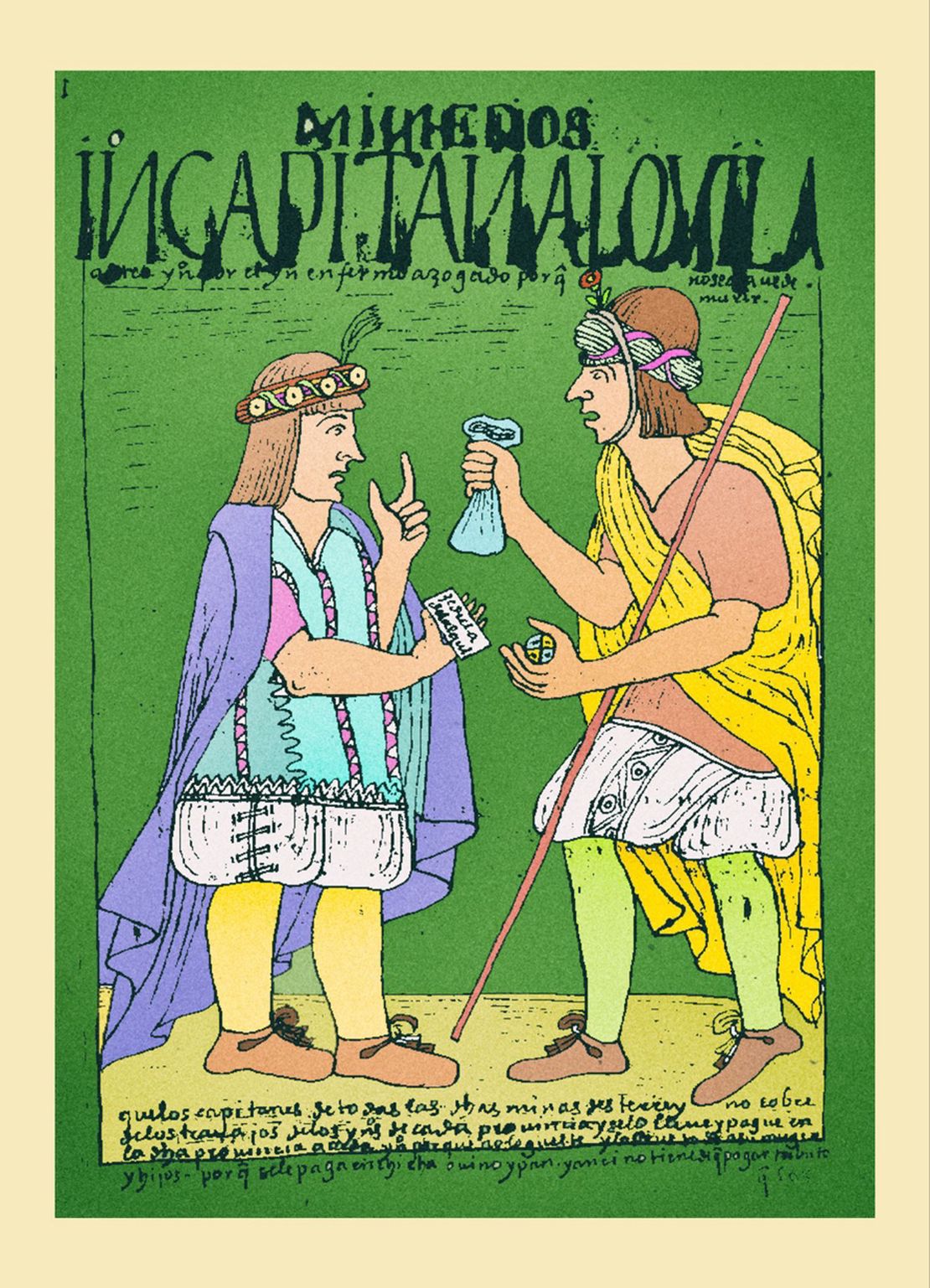

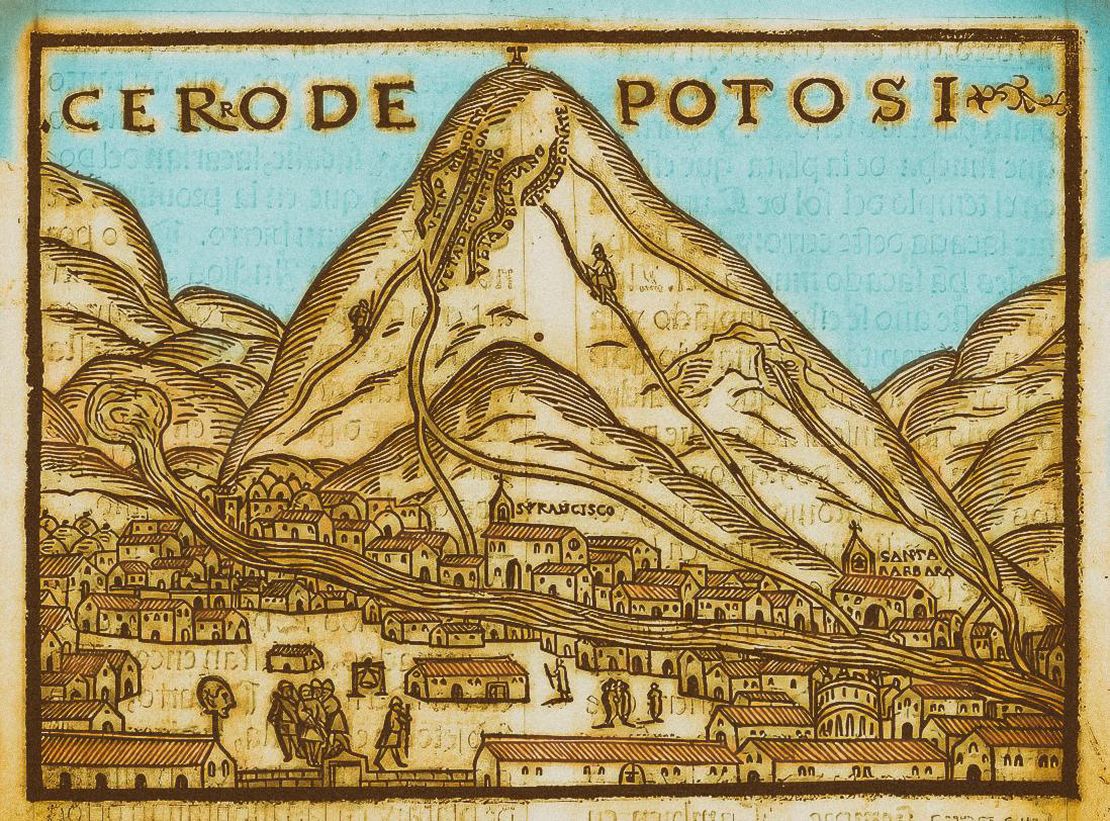

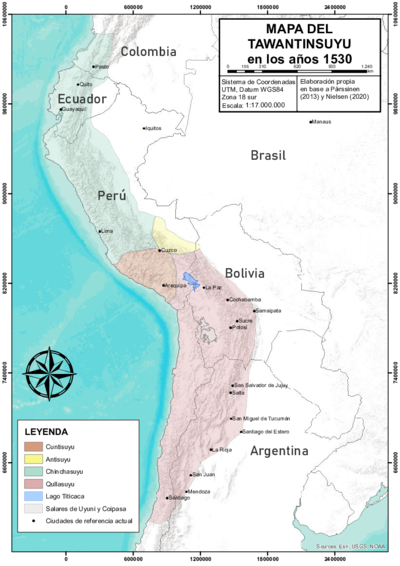

In the midst of the mining crisis and the sharp demographic decline that characterized the 17th and early 18th centuries, and once the conflicts over the succession to the Spanish crown had been overcome —around 1720s—, the Bourbons began to design a series of reforms aimed at centralizing royal power, modernizing colonial administration, and increasing economic efficiency in the management of territories under Spanish rule. The “Reparto forzado de mercancías” —forced distribution of goods— or “repartos” is a term that was used to refer to a new regulation implemented as part of these reforms. In addition to the tributo and the mita that were the most salient institutions implemented during the colonization of the territories outside the Inca state known as Tawantisuyu, the Indigenous people in the Spanish colonies were now forced to acquire products such as clothing, mules and wine at prices fixed by the corregidores and other colonial authorities who managed the trade in a form of monopoly.1 This practice imposed additional economic burdens on the Indians regardless of their actual need or ability to acquire them.

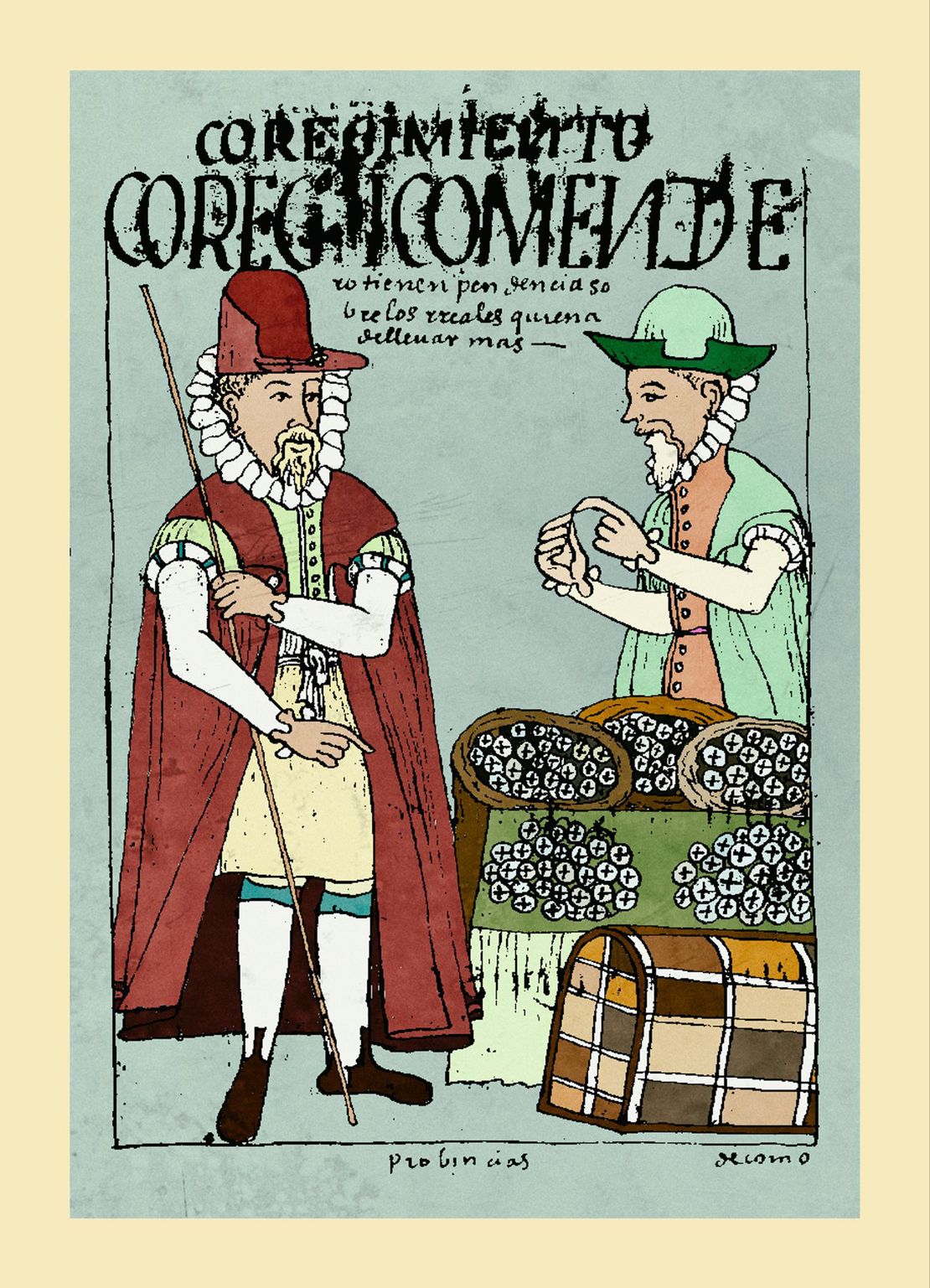

In general, the Bourbon reforms that sought to increase the income of the Spanish crown by ensuring that a greater part of the surplus produced in the colonies reached Spain, were enforced around the 1770s-80s, thus generating a change in the system of colonial administration. Apart from Viceroy Castelfuerte, who in 1734 succeeded in imposing a strong tax reform COLONIAL LEGISLATION AS FRAMEWORK FOR DISPOSSESSIONS IN THE CENTRAL ANDES: THE INDIGENOUS TRIBUTE, 1730s - 1820s , the viceroys who succeeded him limited themselves to institutionalizing partial changes at the local level. In the early 1750s, the crown granted the corregidores the right to distribute a volume of consumer goods to the Indians in their jurisdiction. Thus, from 1754 onwards, the corregidores were able to continue, this time legitimately, with an old practice that had already been widespread since the office of corregidor was put up for sale , almost a century earlier. The crown benefited also because it levied a sales tax on the value of legalized distribution of goods. This tax was the famous alcabala.

Reassured and empowered by the legalization of this practice, the corregidores further strengthened the authority they exercised over the Indigenous people in their jurisdiction, had no qualms about forcing the Indigenous people even more strongly into debt by forcing them to buy goods they had no need of, and took the market to the most remote areas. They also reinforced the other abuses they had been committing, forcing the Indians to work permanently on their haciendas as indebted laborers, in a way that not only stirred greater migration, but also affected the flow of mitayos to Potosí. The corregidores became one more economic actor competing with the mine owners over the Indigenous labor force. The crown remained ambivalent about the conflict between mine owners and corregidores because the revenues from the alcabala were considerable for its own coffers.2

Without restraint or limits, the corregidores pushed plunder beyond bearable levels, often in combination with the kurakas —ethnic authorities that the corregidores themselves elected or imposed. Some studies tend to suggest a direct correlation between the excessive abuses of forced distribution of goods and the massive Indigenous rebellions of Tupac Amaru and Tupac Katari in the 1780-82s.3 Other studies, however, argue that these were due to a broader and more complex set of factors, with the forced distribution of goods being the most visible indicator of a profound transformation in the forms of economic dispossession and the legitimization of a new political structure.4

Bibliography

Andrien, Kenneth. Crisis y decadencia: El virreinato del Perú en el siglo XVII. Lima: Banco Central de Reserva del Perú – Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, 2011.

Choque, Roberto. Jesús de Machaca: La Marka Rebelde. 2nd ed., vol 1. La Paz:

CIPCA, 2003.

Golte, Jurgen. Repartos y Rebeliones: Tupac Amaru y las Contradicciones de la Economía Colonial. Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, 1980.

Larson, Brooke. Colonialismo y Transformación Agraria en Bolivia: Cochabamba 1550-1990.2nd ed. La Paz: Vicepresidencia del Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia, 2017.

Thomson, Sinclair. We Alone Will Rule. Native Andean Politics in the Age of Insurgency. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2002.

Roberto Choque, Jesús de Machaca: la Marka Rebelde (La Paz: CIPCA, 2003), 174. ↩︎

Brooke Larson, Colonialismo y Transformación Agraria en Bolivia, (La Paz: Vicepresidencia del Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia, 2017). ↩︎

Juergen Golte, Repartos y Rebeliones: Tupac Amaru y las Contradicciones de la Economía Colonial (Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, 1980). ↩︎

Sinclair Thomson, We Alone Will Rule. Native Andean Politics in the Age of Insurgency (Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2002). ↩︎