Abstract

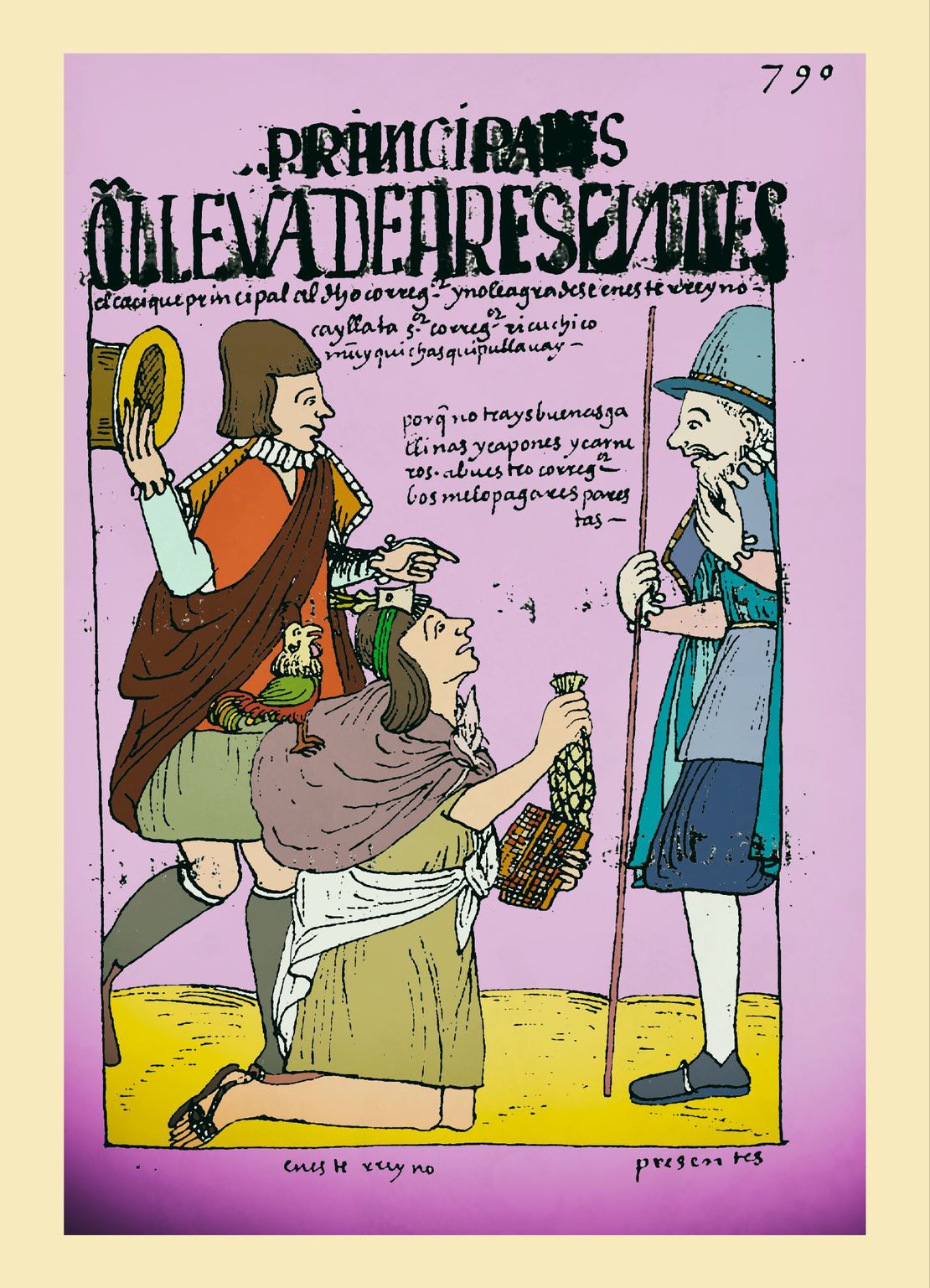

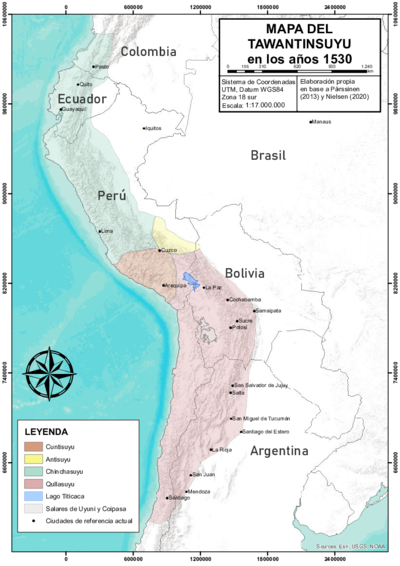

In the 16th century, as of the conquest of the Tawantinsuyu Inca state, the Indigenous people as vassals of the king of Spain were subject to a tribute policy. In the first decades (1530s - 1560s), the initial Indigenous tribute consisted of payments in kind, arbitrary labor services and a commitment to assume payment collectively, but in the 1570s, the Toledo reforms marked a final turn by imposing individualization and monetization of Indigenous tribute. In the context of the mining crisis and strong demographic decline that characterized the 17th and early 18th centuries, there were several failed attempts to readjust the Indigenous tribute to include the large number of Indians who, by fleeing the Pueblos Reales de Indios, or Reducciones, and becoming dispossessed “outsiders”, had managed to escape the taxpayer category. It was only in the 1740s, within the framework of the Bourbon Reforms, that the colonial state managed to impose a new tax regime that included the “outsiders”.

Although the Bourbons took the throne in Spain in 1700, it was not until the 1720s that they began to impose their reforms —due to the wars of succession and other disruptions. The reforms implemented in the 1720s and 1750s were significant as they laid the groundwork for the major and more famous reforms that ensued from the 1760s onwards. These were aimed to establish a more efficient and rational colonial administration, increase the revenues of the Spanish crown, develop more direct and stronger forms of control of the colonial administration, and ensure that a greater part of the surplus produced in the colonies reached Spain.1

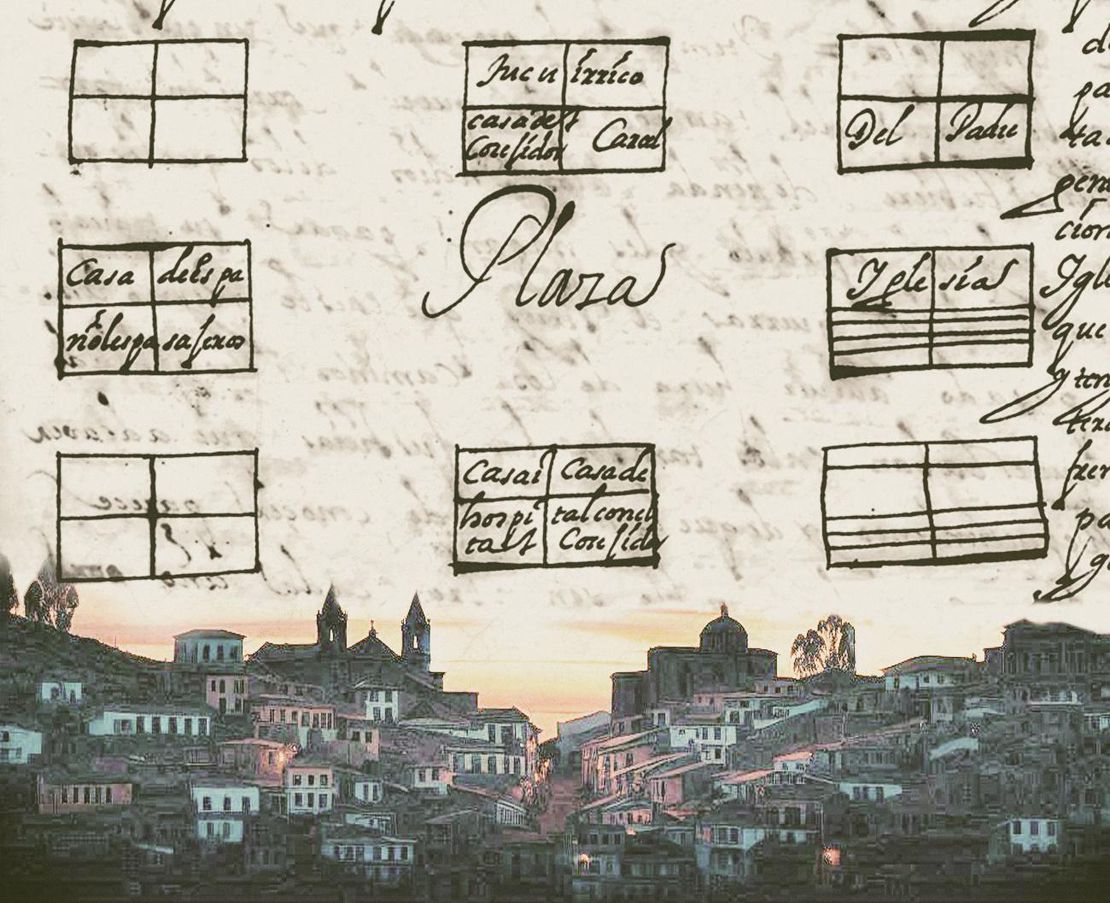

In the Viceroyalty of Peru, the first set of reforms focused, on the one hand, on alleviating the fiscal and mining crisis; and on the other hand, on curbing the access that criollos —sons of Spaniards born in the Americas— had had until then to colonial administration posts, which should be occupied by properly trained peninsulares —Spaniards born in Spain. The second set of major reforms started in the 1770s with the creation of the Viceroyalty of La Plata (1777). However, they were implemented mainly from 1782 onwards in response to the great Indigenous rebellions of Tupac Amaru and Tupac Katari. The territory of the Audiencia de Charcas (Audiencia de La Plata or Alto Perú) —that is, a significant part of what used to be the Qullasuyu— became part of the Viceroyalty of La Plata and in 1782, and was organized into four Intendencias —units larger than the Corregimiento, which would bring together several of the latter —each governed by an Intendente coming directly from Spain—. The Intendente would oversee matters of justice, finance, war, and general administration, which included a more systematic monitoring of the tax and tribute collection. “The concentration of power in the hands of Intendentes was a mechanism of closer royal control over the colonial hinterlands.” 2 The office of corregidor was abolished and the hereditary character of ethnic authorities (caciques or kurakas) was ignored. The forced distribution of goods was also abolished COLONIAL LEGISLATION AS FRAMEWORK FOR DISPOSSESSIONS IN THE CENTRAL ANDES: THE FORCED DISTRIBUTION OF GOODS . However, in many places, the abuses of local colonial authorities —renamed assistant superintendent—, which these reforms sought to curb, continued unabated.

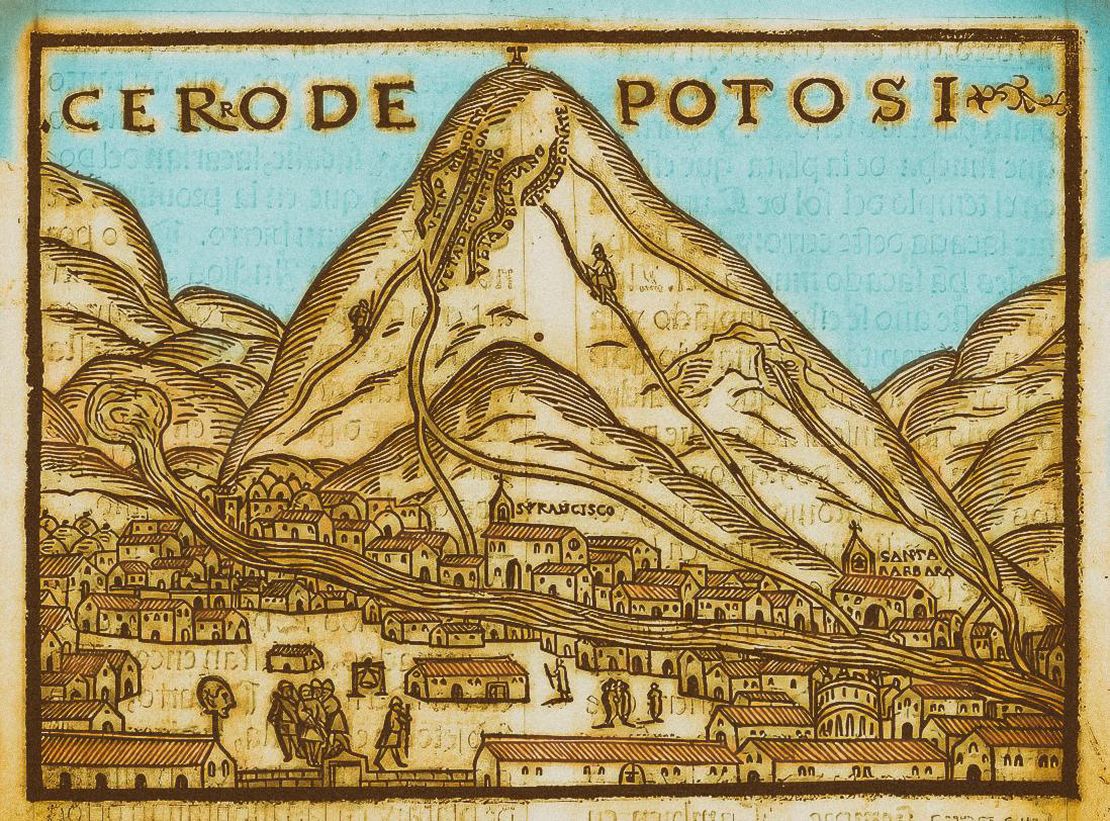

Regarding the Indigenous tribute, the first important reform was introduced in 1734: a general census of the Indigenous population was conducted and all Indigenous people —skilled and fit men— were included in the taxpayer category regardless of their type of access to land. 3 In other words, all outsiders COLONIAL LEGISLATION AS THE FRAMEWORK FOR DISPOSSESSIONS IN THE CENTRAL ANDES: THE INDIGENOUS TRIBUTE 1570s -1620s with some type of access to land and even those mestizos who did not show proof of having a European parent were registered as taxpayers.4 In some provinces, this reform amounted to a 60% increase in Indigenous tribute.5 It should be noted that the differentiation between “originarios” (or “natives”) and “forasteros” (or “outsiders”) was maintained in the fact that the amount of the tribute assigned to the natives was somewhat higher. 6 This reform was implemented more rigorously after 1782 and, above all, after the introduction, in 1786, of more precise procedures to conduct censuses that would yield more accurate data, collect the tribute more effectively and keep a more efficient record of the mitayos in Potosí. By the end of the century, “the Indigenous tribute became the second largest source of royal income [for the Crown] in the Audiencia de Charcas" (own translation). 7

In summary, the tax system reform, which, to include diverse types of “Indians” —natives, other Indians, forasteros COLONIAL LEGISLATION AS THE FRAMEWORK FOR DISPOSSESSIONS IN THE CENTRAL ANDES: THE INDIGENOUS TRIBUTE, 1630s -1720s ****—, defined distinct categories of taxpaying “Indians”, set differentiated amounts for each according to the regions´ productive possibilities, and established an efficient and ruthless collection system. This reorganization was implemented with great force and succeeded in collecting income from Indigenous taxpayers, thus launching “a new taxation cycle that would leave the Indigenous peoples poorer than ever.”**8

For three centuries, the Indigenous tribute stood as an important source of income for the functioning of the colonial state and even of the republican state in its first 50 years. Bolivia was a key source of income for the republican state that was formed with empty coffers after the wars of independence. In what used to be the Tawantinsuyu territory, the Indigenous tribute was significant, and was not abolished until several decades after independence. Namely, in 1854 in the case of Peru, in 1857 in Ecuador, and only in 1874 in the case of Bolivia.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Andrien, Kenneth. Crisis y Decadencia: El Virreinato del Perú en el Siglo XVII. Lima: Banco Central de Reserva del Perú, 2011.

Klein, Herbert. Bolivia. The Evolution of a Multi-ethnic Society. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Larson, Brooke. Colonialismo y Transformación Agraria en Bolivia: Cochabamba 1550-1990. La Paz: Vicepresidencia del Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia, 2017.

Sánchez Albornoz, Nicolás. Indios y Tributos en el Alto Perú. Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, 1978.

Pearce, Adrian. The Origins of the Bourbon Reform in Spanish South America, 1700-1763. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

Reform in Spanish South America, 1700-1763.

Adrian Pearce, The Origins of the Bourbon Reform in Spanish South America, 1700-1763 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014). ↩︎

Brooke Larson, Colonialismo y Transformación Agraria en Bolivia: Cochabamba 1550-1990 (La Paz: Vicepresidencia del Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia, 2017), 342. ↩︎

Herbert Klein, Bolivia. The Evolution of a Multi-ethnic Society (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, 1992), 73. ↩︎

Larson, Colonialismo y Transformación Agraria en Bolivia; Pearce, The Origins of the Bourbon ↩︎

Pearce. The Origins of the Bourbon Reform in Spanish South America, 106. ↩︎

Sánchez-Albornoz, Indios y Tributos en el Alto Perú (Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, 1978). ↩︎

Klein, Bolivia. The Evolution of a Multi-ethnic Society, 72. ↩︎

Larson, Colonialism and Agrarian Transformation in Bolivia, 356*.* ↩︎

](/images/content/TL009Tributo/image1_hu25f2bd8054929c1fdce937ac7cc1e543_575580_1110x0_resize_q80_lanczos.jpeg)