Abstract

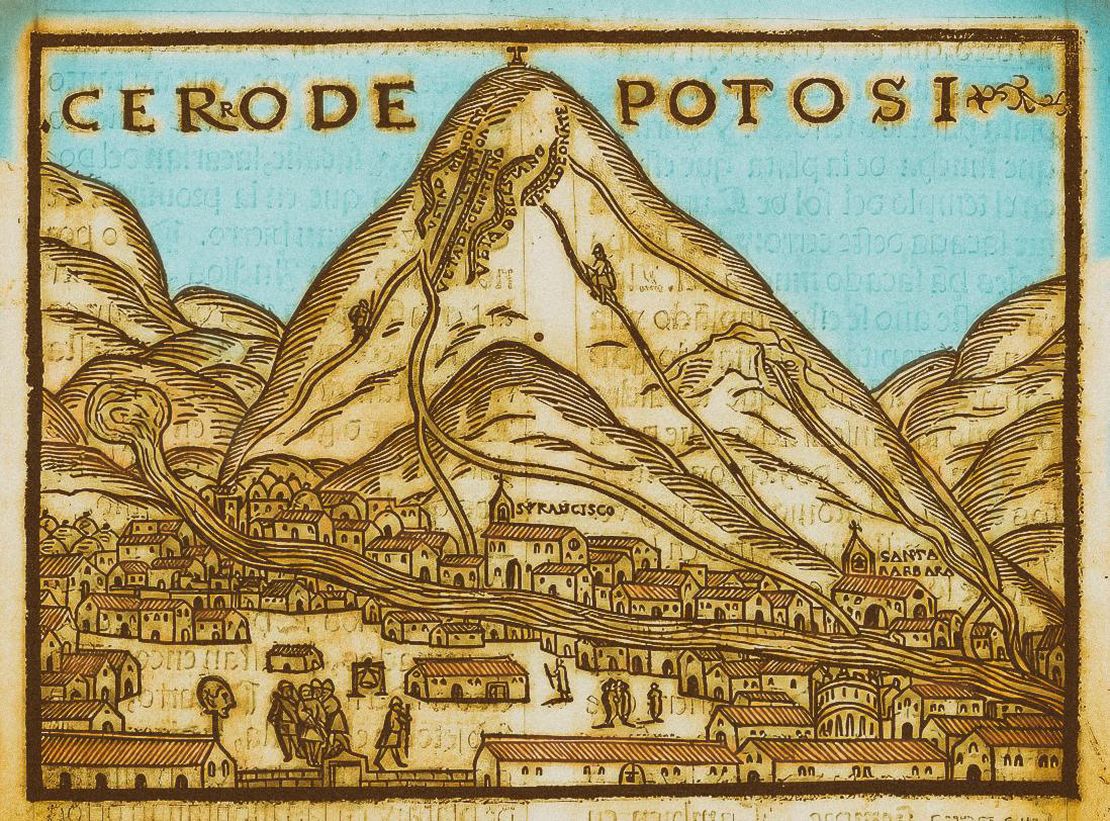

In the context of the mining crisis and the sharp demographic decline that characterized the 17th and early 18th centuries, and once the conflicts over the succession of the Spanish crown had been overcome —in the 1720s—, the Bourbons drafted a series of reforms aimed at centralizing royal power, modernizing the colonial administration, and increasing economic efficiency in the management of territories under Spanish rule. However, the crown did not manage to enforce most of these reforms either because they encountered much opposition in the colonies or because these were not able to produce more revenue. This was the case of the Viceroyalty of Peru, faced with a strong demographic crisis, as silver mining —its main source of wealth—, was in decline. In 1633, this circumstance made the crown decide to put high-ranking fiscal posts up for sale. A few years later, in 1678, the post of “Corregidor”, the authority in charge of collecting the Indigenous tribute, was also put up for sale, thus generating the conditions for greater corruption, exploitation and plundering.

During the 17th century, while Spain gradually lost the leadership it had exerted at the beginning of the European colonial expansion, England gained greater hegemony. A series of factors, including the wars in Europe and the inadequate administration of its colonies, spawned a serious fiscal crisis that the Spanish crown tried to remedy through fiscal reforms aimed at increasing the tax burden. One of these rentier measures enforced was to put the office of corregidor up for sale. In this way, the crown would willingly grant power and incentives to these authorities in exchange for a secure and uninterrupted income.1 According to Andrien, through this measure, the crown enabled a group of officials —in most cases inexperienced, dishonest and with strong local connections—, to gain control of the central agencies of the treasury .2

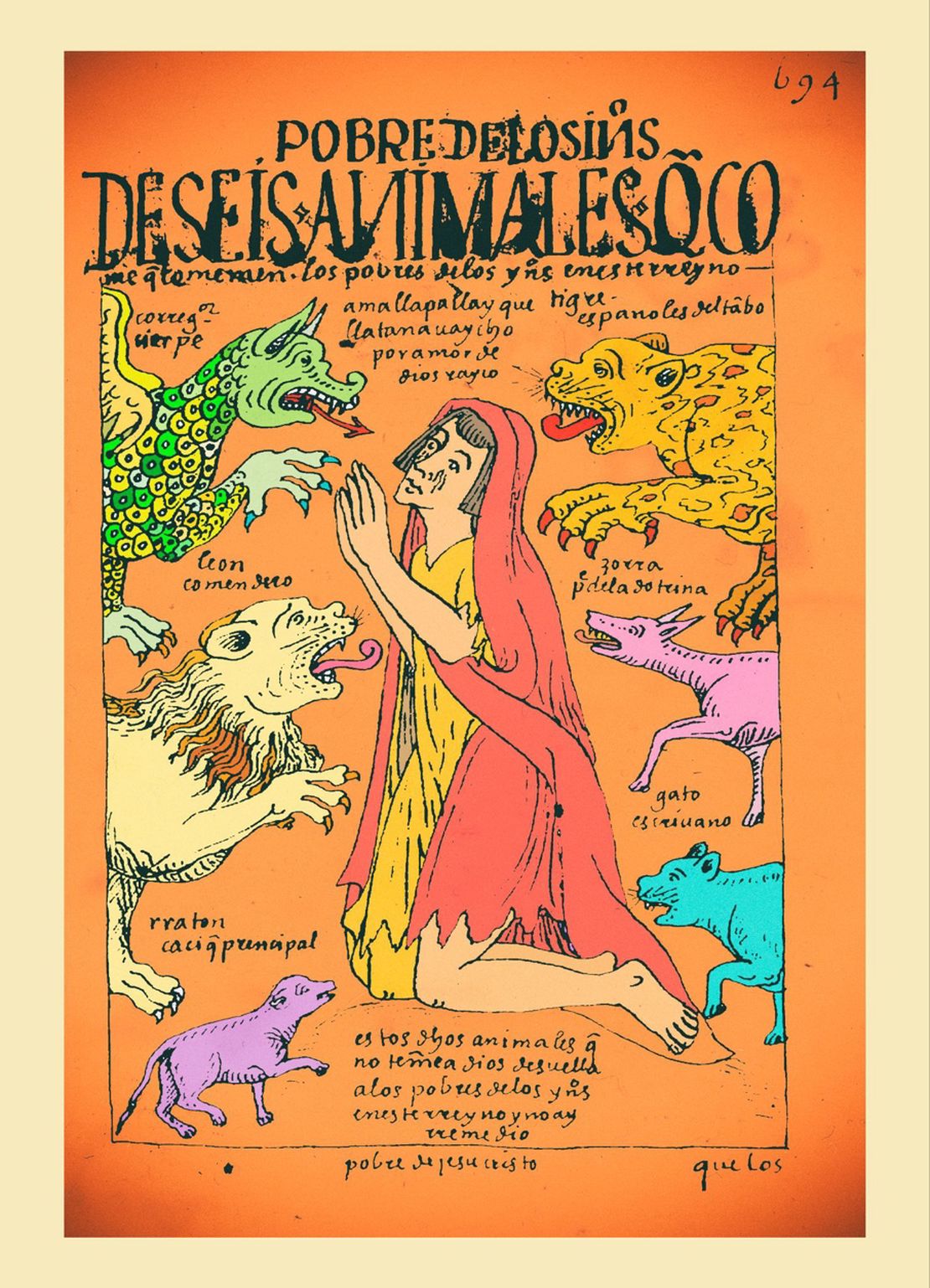

Subordinated to the viceroyalty power and to the judicial audiencia´s authority, the post of corregidor was the highest rank at the provincial level. With the Toledo reforms organizing the territory of each audiencia by dividing it into provinces or corregimientos, the corregidor oversaw the collection of the Indigenous tribute, administering justice and “protecting the natives”, among other competencies. As Larson observes, “the commodification of this position led to the emergence of provincial bureaucrats whose authority and conduct went virtually unchecked. The spread and accrual of power among provincial authorities reduced the viceroy’s ability to intervene in local affairs or among conflicting interest groups.” 3 In other words, this measure opened the door to all kinds of fraudulent and corrupt practices and abuses of power by local colonial authorities.

For the Indigenous communities located in the provinces of the Audiencia de Charcas, the impact of this measure was devastating. These areas were far from the concentration of vice royal power, so the corregidores “had twisted all the measures decreed by the crown […] and shamelessly exploited the work and resources of the Indigenous people under their control,” thus becoming “a second cog in the wheel of plunder.”4

The corregidores enriched themselves by committing abuses in four primary areas. The first and most common was the repartimientos de mercancías —or goods distribution—, which delivered goods three times a year in a forced manner: mules, clothes, wine, coca, corn, flour along with other useless merchandise. Secondly, the trajines: they functioned as intermediaries or go-betweens between sellers of these products in other regions. They would send herds of animals to carry and transport the cargo, forcing the Indians to travel with their animals for a small commission that did not cover the many risks involved in the journey. All of this meant that the profit margin for the corregidor grew by five times his initial investment. The third area where abuses were committed was land confiscation: they confiscated the lands of the Indigenous debtors and thus contributed to the expansion of the hacienda. Finally, there was the renting out of laborers: postponing the service of the crown for the benefit of private individuals, they rented Indigenous workers out to the Spanish hacienda owners, especially in the region that today belongs to Peru. 5

The former abuses committed by the corregidores, which further aggravated the pressure of tribute and mita mechanisms, amplified even more when in the 18th century the Spanish crown legalized the forced distribution of goods, one of the factors that would trigger the 1780-82 Indigenous rebellions in the Andes region. The corregidor position was abolished in 1782 when the crown conducted a complete restructuring of the administrative political division, creating Intendencias along with the “Intendente” position, replacing that of “Corregidor”.

Bibliography

Andrien, Keneth. Crisis and Decadence: The Viceroyalty of Peru in the XVII Century. Central Reserve Bank of Peru - Institute of Peruvian Studies, 2011.

Larson, Brooke. Colonialism and Agrarian Transformation in Bolivia: Cochabamba 1550-1990. La Paz, Bolivia: Vicepresidencia del Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia, 2017.

Sánchez Albornoz, Nicolás. Indians and Tributes in Upper Peru. Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, 1978.

Vicepresidencia del Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia, 2017), 180.

Vicepresidencia del Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia, 2017), 167.

Brooke Larson, Colonialismo y Transformación Agraria en Bolivia: Cochabamba 1550-1990 (La Paz: ↩︎

Kenneth Andrien, Crisis y Decadencia: El Virreinato del Perú en el Siglo XVII. (Lima: Banco Central de Reserva del Perú – Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, 2011), 135. ↩︎

Larson, Colonialismo y Transformación Agraria en Bolivia: Cochabamba 1550-1990 (La Paz: ↩︎

Nicolás Sánchez-Albornoz, Indios y Tributos en el Alto Perú. (Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, 1978), 96. ↩︎

Sánchez-Albornoz, Indios y Tributos en el Alto Perú, 97-99. ↩︎

. Intervened digitally by Mauricio Sánchez Patzy.](/images/content/TL008Venta/image1_hu08927b64e8331532022bf0dd5cd194c0_529521_1110x0_resize_q80_lanczos.jpg)