Abstract

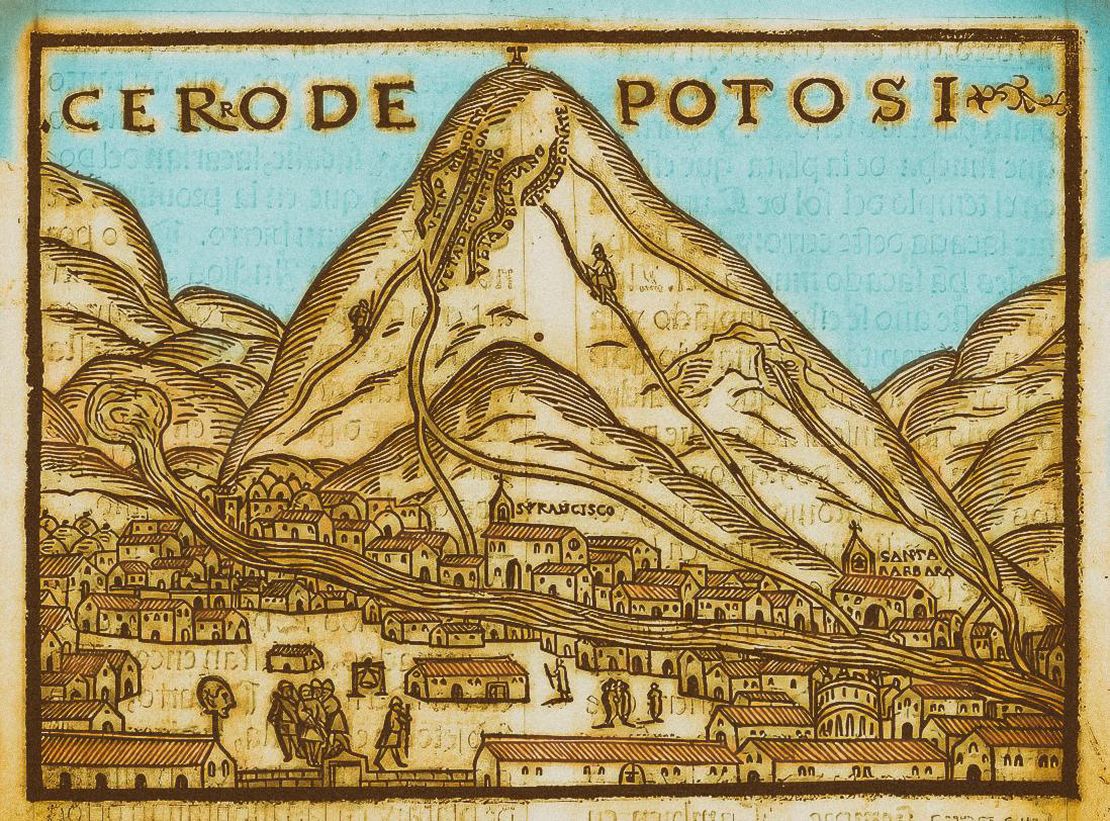

Once the Spanish conquered Tawantinsuyu-name of the Inca state─, they imposed an initial Indigenous Tribute over the first decades (1530s - 1560s), which consisted of in-kind payments, arbitrary labor benefits and the collective responsibility to shoulder payment. By the 1570s, Toledo`s Reforms imposed the individualization and monetization of the Indigenous tribute. Often described as a period of silver mining crisis and decline of the Spanish Empire, the 17th century was also a time of changes triggered by various local powers and social (economic) actors in reaction to the unsuccessful attempts of the Spanish crown to impose new reforms. The demographic crisis produced by the sharp decline of the Indigenous population throughout the 17th century meant that the Indigenous people could no longer withstand the pressure of the high tax burden, which generated new phenomena, such as the growth of forasteros or outsiders.1

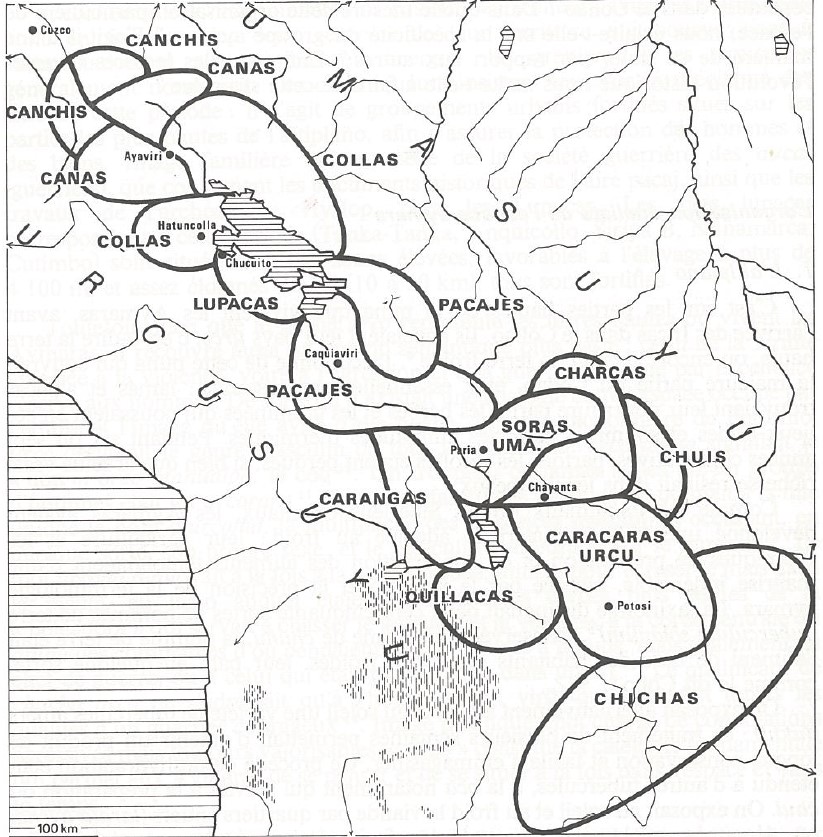

In the viceroyalty of Peru and particularly in the Audiencia de Charcas ─economic area around Potosí─, this period was marked by a strong demographic crisis, a persistent decrease in the silver production volume, and a serious fiscal crisis linked to the inability of colonial authorities to control the situation or impose new reforms. These three crises were interrelated and affected in various ways the different regions and each of the different social and economic actors in the 16 provinces subject to the mita mechanism of Potosí, most of which were in the districts of La Paz and Charcas, today in Bolivian territory.

The Indigenous population declined steadily ─although unevenly depending on the region─ throughout the 17th and early 18th centuries. It was not until the 1730s that the demographic curve began to rise again. In spite of many claims and attempts, the few censuses that were made were partial and unreliable. It was not until the 1680s that the viceroy in office, Duke of La Palata, managed to conduct a census of a magnitude comparable to the one taken during Viceroy Toledo´s “visita general” in the 1570s. On comparing both censuses, it is estimated that the Indigenous population in the provinces near Potosí decreased by 42% in those 110 years.2

This demographic decline was not only due to epidemics and diseases, but also to the massive emigration of taxpayers who escaped from the reducciones to avoid the pressure of the tribute and the mita in Potosí. This unexpected effect of Toledo´s Reducciones program is linked to the residency principle imposed by the Spanish and used in the definition of tax categories. According to this principle, the tax category of “native” corresponds to skilled and fit men residing in the reduction village where they had access to land. Upon fleeing the town, abandoning their fixed residence or place of abode, they would become “outsiders” and would cease to have tax obligations, but also lost the right of access to land. This is how taxpayers escaped to other Indigenous villages, to the cities, to the mines to work for wages, or to the agricultural haciendas to work as tenant farmers or day laborers. The flight of these “natives” affected tax collection and the availability of Mitaya labor in the mines of Potosí.

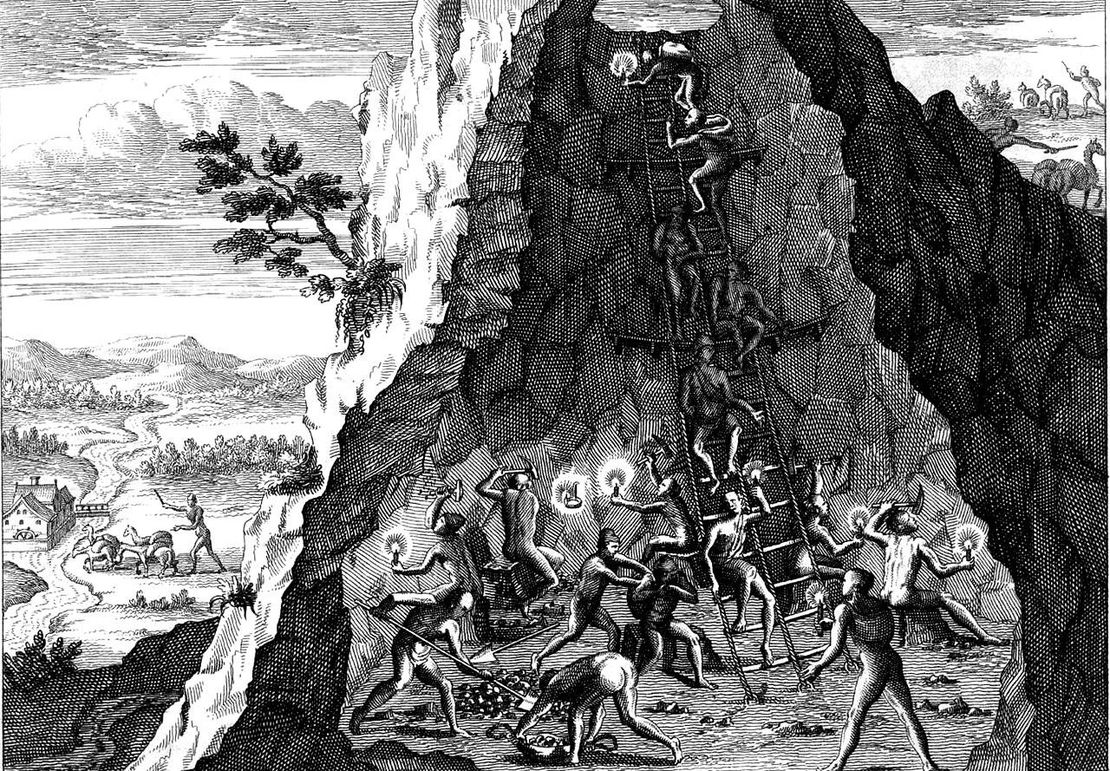

Indeed, the decline of mining was due not only to the reduction in the grade of the minerals extracted, but also to the shortage of Mitaya labor. At its peak, in the 1590s, Potosí produced 800,000 silver marks, then began to decline, producing only 600,000 in the 1630s, 400,000 in the 1660s and less than 200,000 at its lowest point in the 1740s.3 Although there was a recovery towards the end of the 18th century, silver production in Potosí never went back again to the volume reached in the 1590s.

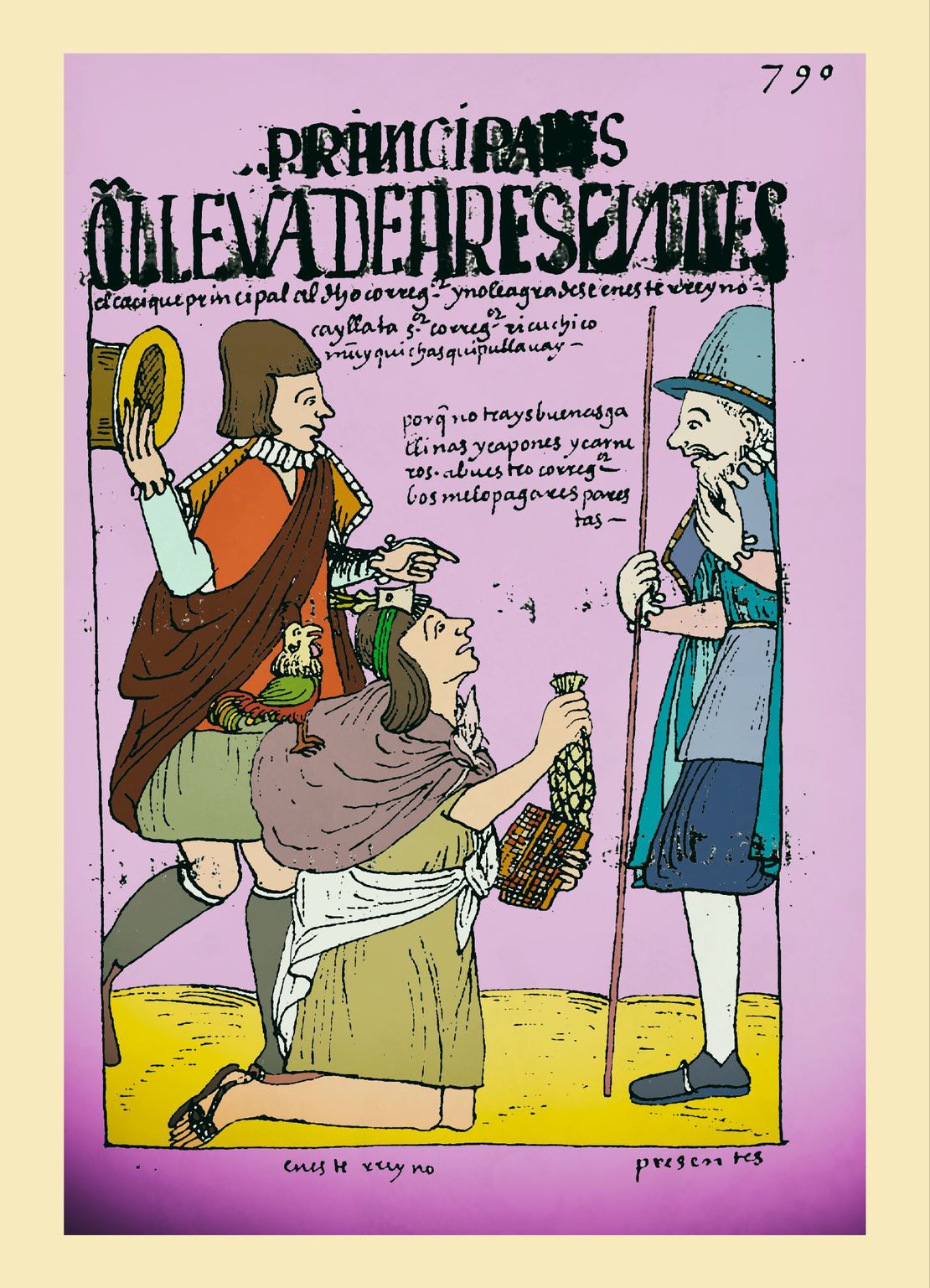

Throughout the 17th century, the Spanish mine owners made several demands asking for the intervention of the colonial state to force the Indigenous communities to comply with their mitayos quota ─or pay in money what it would cost to replace them with wage-earning workers─, to carry out new censuses to adjust tribute and mita mechanisms, and/or to make the “outsiders” a taxpaying/mitayos category. When finally in the 1680s a general census was conducted and the “outsiders” were registered, it was found that in the 16 provinces subject to the mita, this category amounted to 48.5% of the Indians of taxpaying age.4 The viceroy of La Palata then ordered to include the outsiders as taxpayers. However, neither he nor his immediate successors succeeded in imposing these measures. The La Palata census was plagued with criticism, the debates surrounding the mita and tribute were very controversial, and the vice royal authorities were unable to resolve the conflicting interests of the different economic actors. The Spanish mine owners supported the inclusion of outsiders in the tribute and mita, but estate owners opposed it because outsiders were the captive labor force from which they benefited: miners and hacienda owners competed over the Indigenous labor force. Even if the Spanish authorities had wanted to take a stand in this conflict, the underlying problem was structural: the colonial state had lost its capacity to either rebuild the Toledo model of expropriation or impose a new one.5

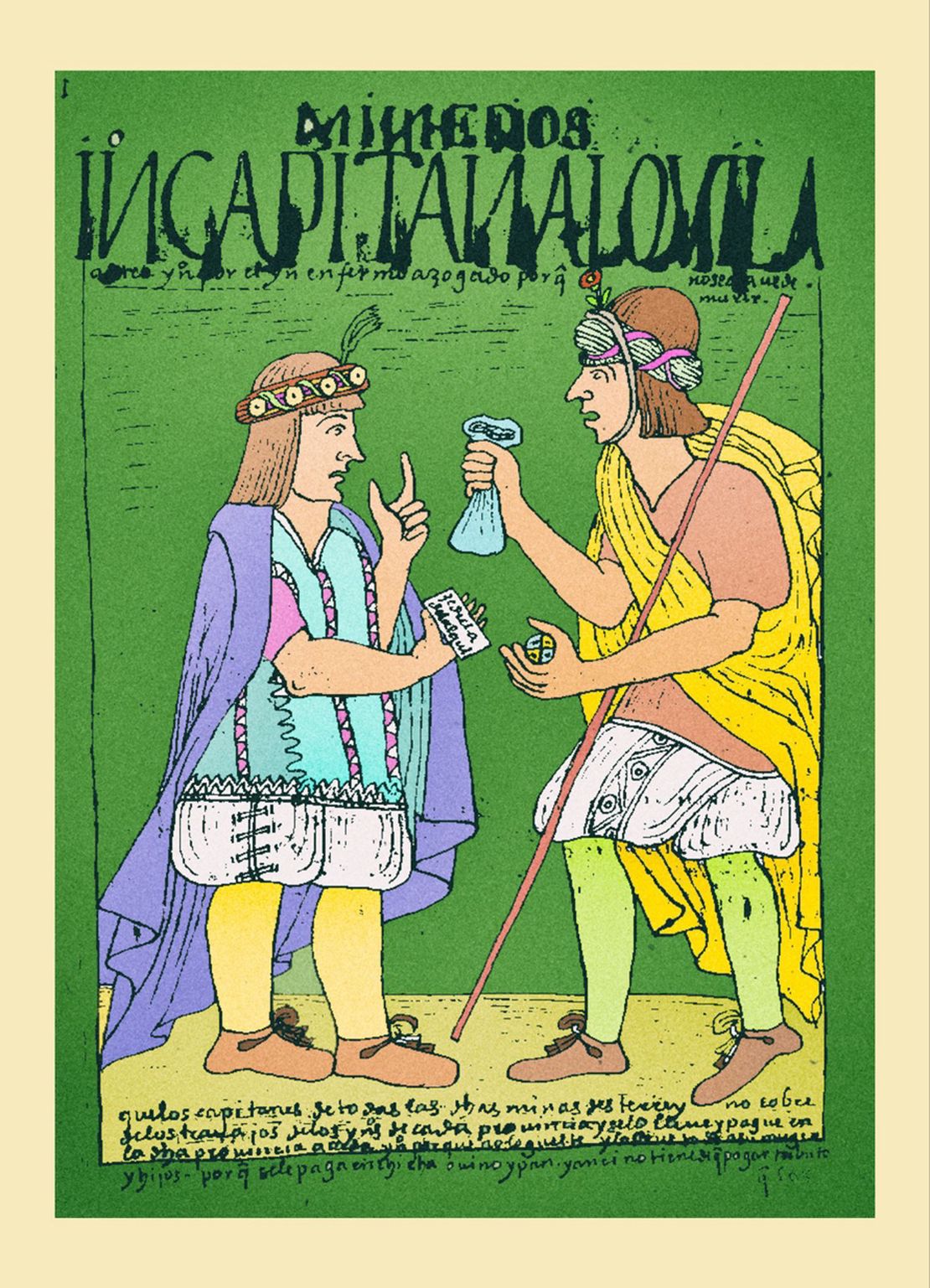

In this period´s complex scenario, there were no new tax laws: the Toledo laws remained in force on paper, but the colonial authorities did not know how to maintain the fragile balance that Toledo´s Reforms required to capture surplus and Indigenous labor force in a sustainable manner, or else to control the market forces that these same reforms had unleashed. Nor did they know how to respond to the diverse ways in which the Indigenous people resisted the impact of the tax pressure, or to stop the abuses that, in many places, were committed by the local authorities in charge of collecting the tribute.

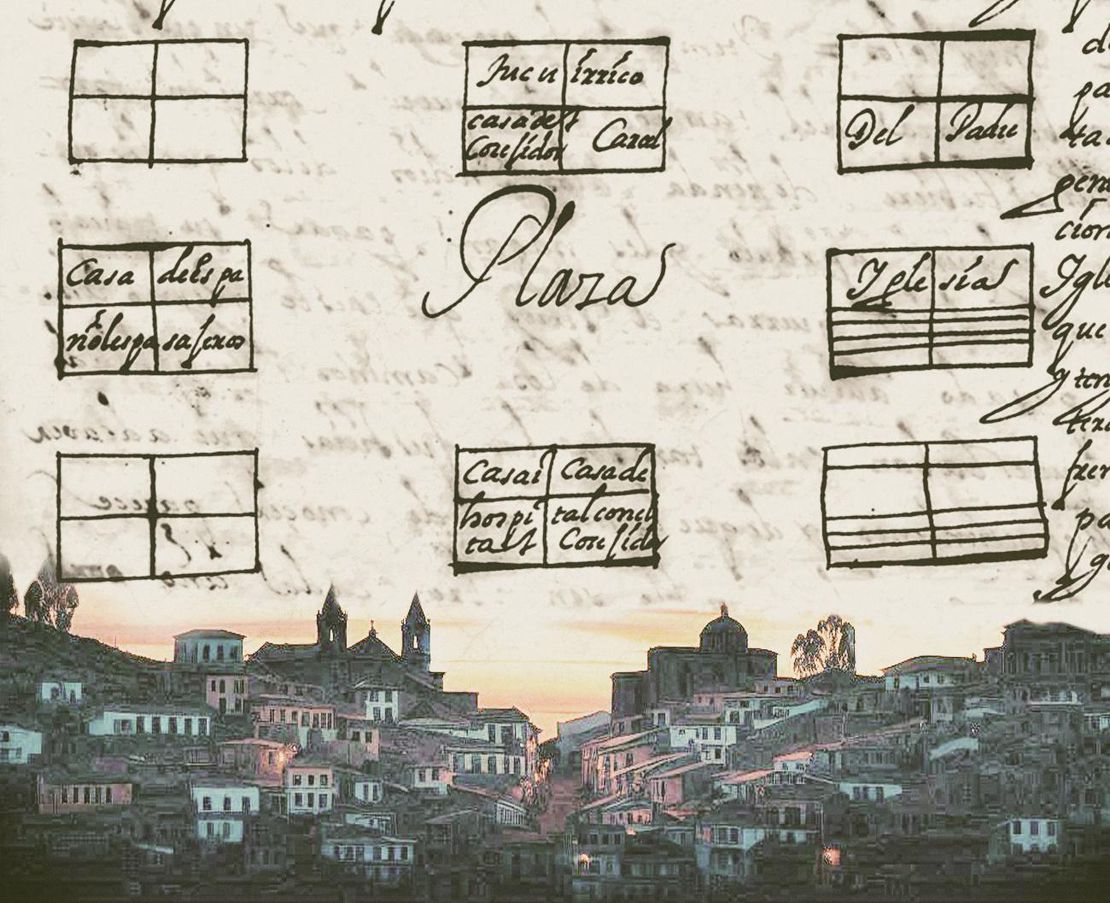

Under Toledo’s reforms, each “pueblo Real de Indios” (reducción) owned land collectively for sustenance and surplus production. The land, in theory, was not to be sold. The original residents of that town, as members of that “common” of Indians (“common” and “community” are the terms used in colonial documents of the time) had access to the lands and ─therefore─ had to comply with the tribute and mita. Although the tribute amount and the number of mitayos were calculated based on the number of individuals ─skilled and fit men─, the payment of the tribute and fulfillment of the mita were the responsibility of the community. Since the amount was fixed during the censuses, it could only be modified with a new census ─“visita general” or “revisita” as they were called at the time. This did not happen until the 1680s, as mentioned above, and it did not do much good either because the La Palata modifications were not implemented. Therefore, the official amount throughout this period was the one fixed in the 1570s during the “general visit” of Viceroy Toledo. That is, throughout this period, each Indigenous community was responsible, through its authority, the kuraka, for paying the amount of tribute and mita fee corresponding to the number of taxpayers registered in that community in the 1570s censuses.

It is not difficult to imagine the impact that the demographic crisis had on these communities: the tax and mitaya pressure became increasingly unsustainable and the difficulties to cover amounts and quotas were greater and greater. Faced with the inertia of the colonial state, both the Indigenous communities and the local authorities directly in charge of collecting the tribute generated their own strategies to deal with the situation. Not all the original taxpayers who fled ─therefore becoming forasteros or outsiders broke ties with their communities or disengaged from their tax obligations. Persecuted and pressured by their kurakas or even of their own accord, they would send the amount corresponding to their share of the tribute and to what they would earn for serving in the mita in Potosí; this amount would be obtained by selling their labor force in the market. In other cases, it was the hacienda owners who, under pressure from the corregidores, agreed to pay the corresponding amount to the outsiders who worked on their haciendas, thus generating debt peonage.

Many kurakas also developed other strategies to raise the money to fulfill their tax and mitaya obligations: sale and lease of common lands, sale, and lease of animals, increase of the fees for those taxpayers still in the community, sale of agricultural products (produced by the community members) in the markets, etc. These strategies not only implied a greater integration into the market, but also opened the door to all kinds of abuses and corruption. In general, in this period and despite the efforts, the amounts of tribute collected and the number of mitayos in Potosí were always lower than those fixed in Toledo’s time.

In summary, the diverse ways in which Indigenous communities faced the pressure of tribute and mita triggered a great diversity of situations depending on the region and context, but also implied a greater integration and dependence on the market. In many areas of the Altiplano, Indigenous communities ─reassembled in ayllus as of the Toledo Reducciones─ managed to maintain internal cohesion and consolidate themselves by articulating an ethnic (domestic) economy and a (external) participation in the market economy. In general, however, the growing integration of Indigenous peoples into the market and the consolidation of the internal market in the southern Andean economic area stirred processes of socioeconomic differentiation within the communities, between Indigenous peoples with land and Indigenous peoples without any land, and the subsequent fragmentation or disintegration of Indigenous communities. The Bourbon Reforms of the 1740s tried to rectify the situation through new tax readjustments, which included the expanded Indigenous tribute for outsiders.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Andrien, Kenneth. Crisis y Decadencia: El Virreinato del Perú en el Siglo XVII. Lima, Perú: Banco Central de Reserva del Perú, 2011.

Klein, Herbert. “Fiscalidad Real y Gastos de Gobierno.” Documento de Trabajo del IEP no. 66 (1994): 39.

Larson, Brooke. Colonialismo y Transformación Agraria en Bolivia: Cochabamba 1550-1990. La Paz, Bolivia: Vicepresidencia del Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia, 2017.

Sánchez Albornoz, Nicolás. Indios y Tributos en el Alto Perú. Lima, Perú: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, 1978.

Vicepresidencia del Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia, 2017).

Kenneth Andrien, Crisis y Decadencia: El Virreinato del Perú en el Siglo XVII. (Lima, Perú: Banco Central de Reserva del Perú, 2011). ↩︎

Nicolás Sánchez-Albornoz, Indios y Tributos en el Alto Perú (Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, 1978), 27. ↩︎

Herbert Klein, “Fiscalidad Real y Gastos de Gobierno.” Documento de Trabajo del IEP no. 66 (1994): 39. ↩︎

Sánchez-Albornoz, Indios y Tributos en el Alto Perú, 49 y 77. ↩︎

Brooke Larson, Colonialismo y Transformación Agraria en Bolivia: Cochabamba 1550-1990. (La Paz: ↩︎

](/images/content/TL007Tributo/image1_hua55292986bca188f08b5b40420ce3c38_81843_1110x0_resize_q80_lanczos.jpg)