Abstract

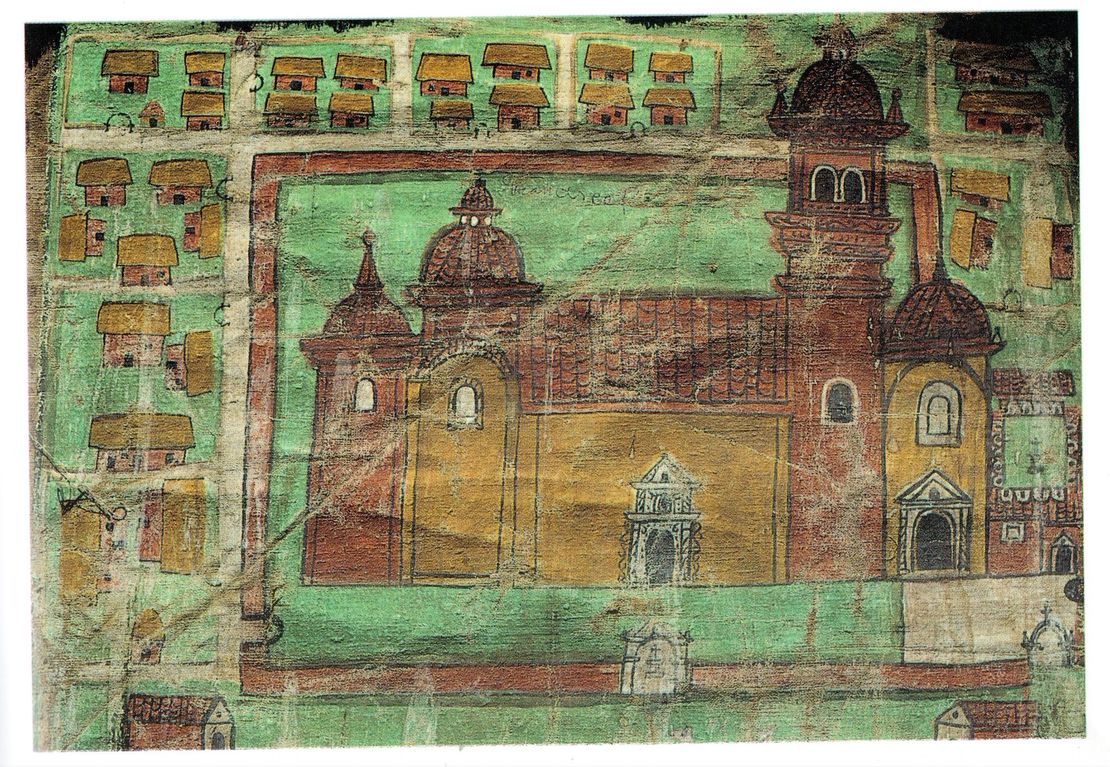

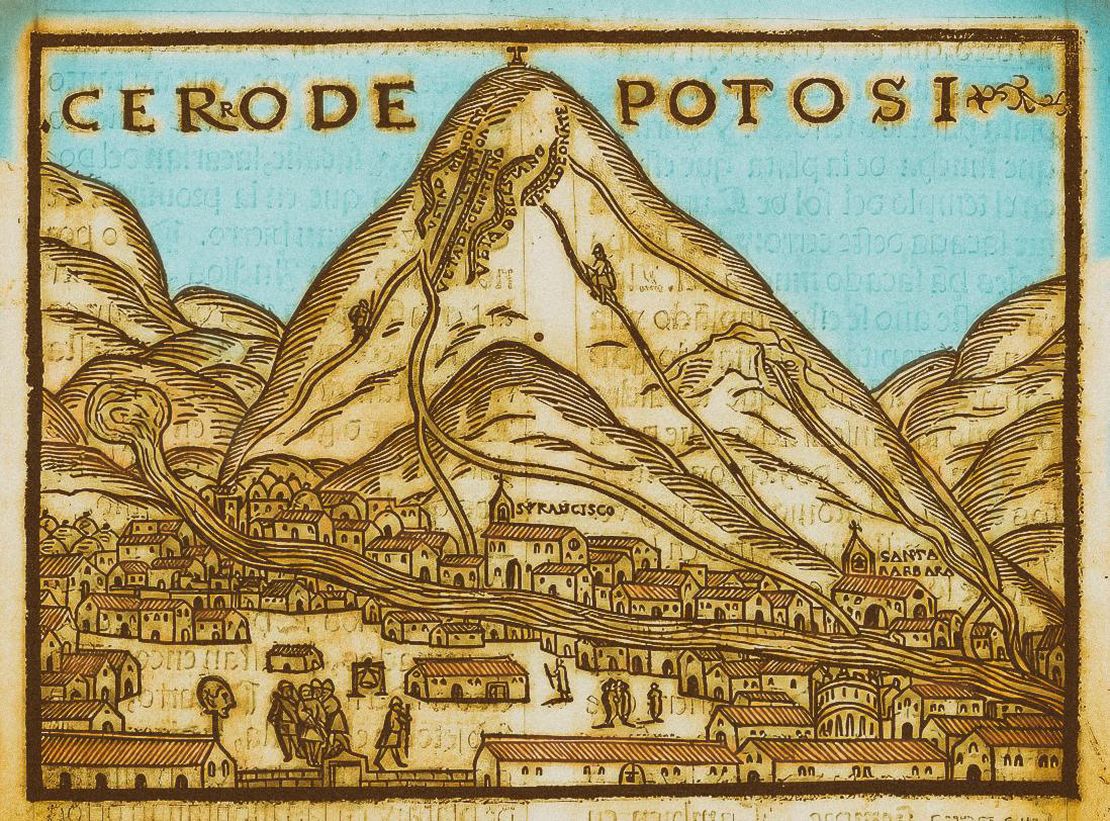

Land composition was a legal classification and structure in Castilian law that enabled to legalize the undue encroachment of land, or the illegal status of foreigners, through a payment to the Royal Treasury. At the end of the 16th century, through the application of this legal figure to its colonies´ territories, the Spanish Crown found a substantial source of income to finance its wars in Europe.1 Thus, starting in the 1590s, land composition classifications were initiated in the territories of what used to be the Qullasuyu, southern district of the Inca state, or Tawantinsuyu, and across the Viceroyalty of Peru. With the application of this legal figure, the mercantilization of land began, facilitating and legalizing the expansion of haciendas and large estates, along with the territorial dispossession of Indigenous communities.

Through land composition, a de facto condition, whether non-compliant with or against the law, would become ─as a desired effect─, a de jure situation. The negotiation or agreement mechanism between the sovereign and his subjects enabled both parties to end up benefiting: the vassal would amend the irregularity, and the Crown would profit from the corresponding monetary contribution.2 In the case of royal lands, the composition was not an original ownership title, as was the royal grant or gracia real, “but a legal act by which the illegal situation could become legal, generating another type of title that protected the right of the bearer, and that ultimately granted him absolute possession.”3 Thus, shortly after the consolidation of the colonial state in the Viceroyalty of Peru, the Spanish Crown prepared the legal instruments to justify the occupation of lands and impose its sovereignty, validating a doctrine composed of three key elements:4

Recognition of Indian power over their lands,

ius gentium, i.e., the appropriation of land by the sovereign through the right of war, in this case a war won against the Inca state,

the sovereign´s ius eminens, fundamentally over the territory that granted him ownership over all lands considered “wastelands.”

The ius gentium granted the European monarch the right to inherit the income, along with the state and inherited lands of the native monarch. Consequently, in the Andean case, the European appropriation took place on the lands that, under the Inca state, were assigned for exclusive use by the Inca or by those in charge of the temples of the Sun. These properties, now considered “royal or crown lands,” began to be granted through “land grants.”

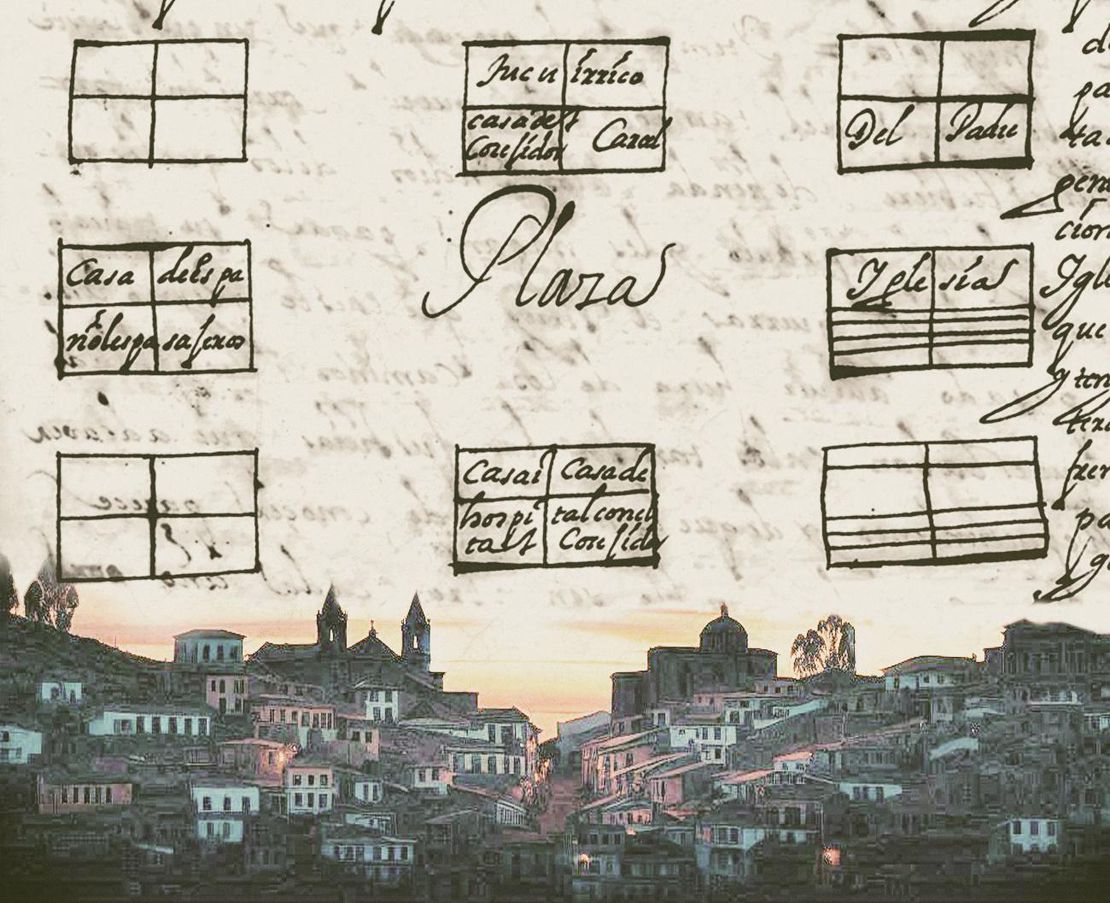

In order to increase the revenues of the Royal Treasury, at the end of the 16th century, the Spanish Crown imposed a tax on the public compositions and auctions of the royal lands.5 It was at this stage that the Spaniards began a second cycle of occupation of the lands that were being depopulated by the native demographic collapse caused by various epidemics and by the mandatory concentration of Indians in the Toledo Reducciones. The Crown ordered to demarcate the farming and breeding area needed by the “Indian” villages so that “all the rest of the land would be free and clear to grant and dispose of it at our will.” 6 In the same way, the Crown issued a decree regarding European colonizers, to proceed to land composition by means of a monetary payment on the lands that they had awarded through grants, and those that had been occupied illegally.

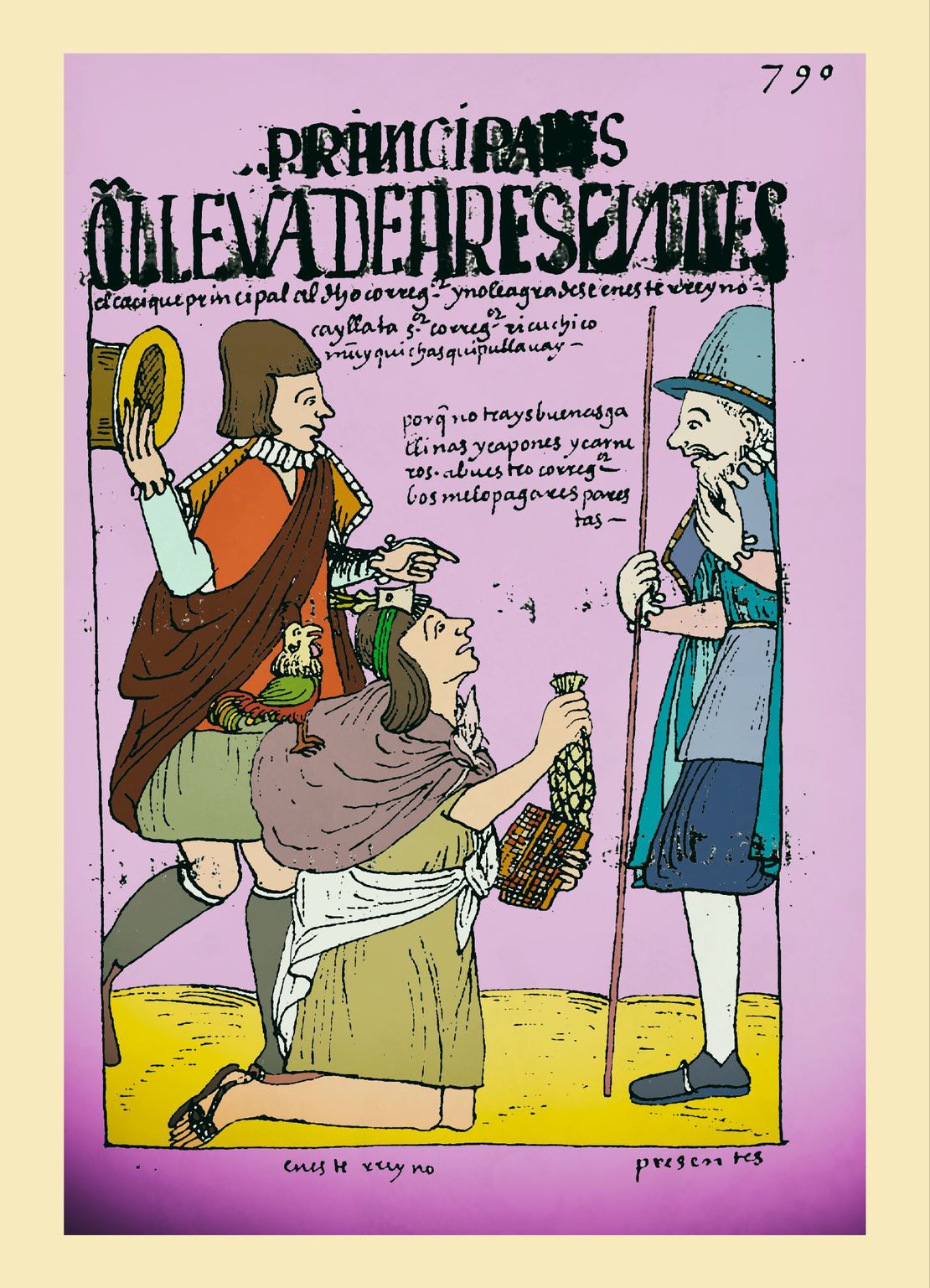

In the Viceroyalty of Peru, this expansion was legitimized by the Royal Decree of 1591, thus initiating the compositions period.7 This regulation was carried out between 1593 and 1594, at the same time that the so-called “wastelands” were auctioned off, through a swift operation that derived in a substantial income for the royal treasury.8 However, the compositions of 1598, 1620 and 1630 were part of the regularization program that gave rise to noticeable speculation. Since Andean agricultural technology was based on a crop-rotation system that left much land fallow, this situation offered speculators an opportunity to claim land that was uncultivated at a given point in time.9 Still this would have a more profound macroeconomic impact with an already irreversible effect: successive land compositions generated a process of privatization by which many Indian elites began to differentiate themselves from their poorer relatives. Legally, the judge of a composition could sell all the lands of a community considered “surplus” to those who requested a private property title. In turn, compositions also allowed wealthy Indians to buy the auctioned lands, and Indian authorities (kurakas) to “privatize” their traditional land use rights, thus promoting the beginning of the commodification and private ownership of land.10

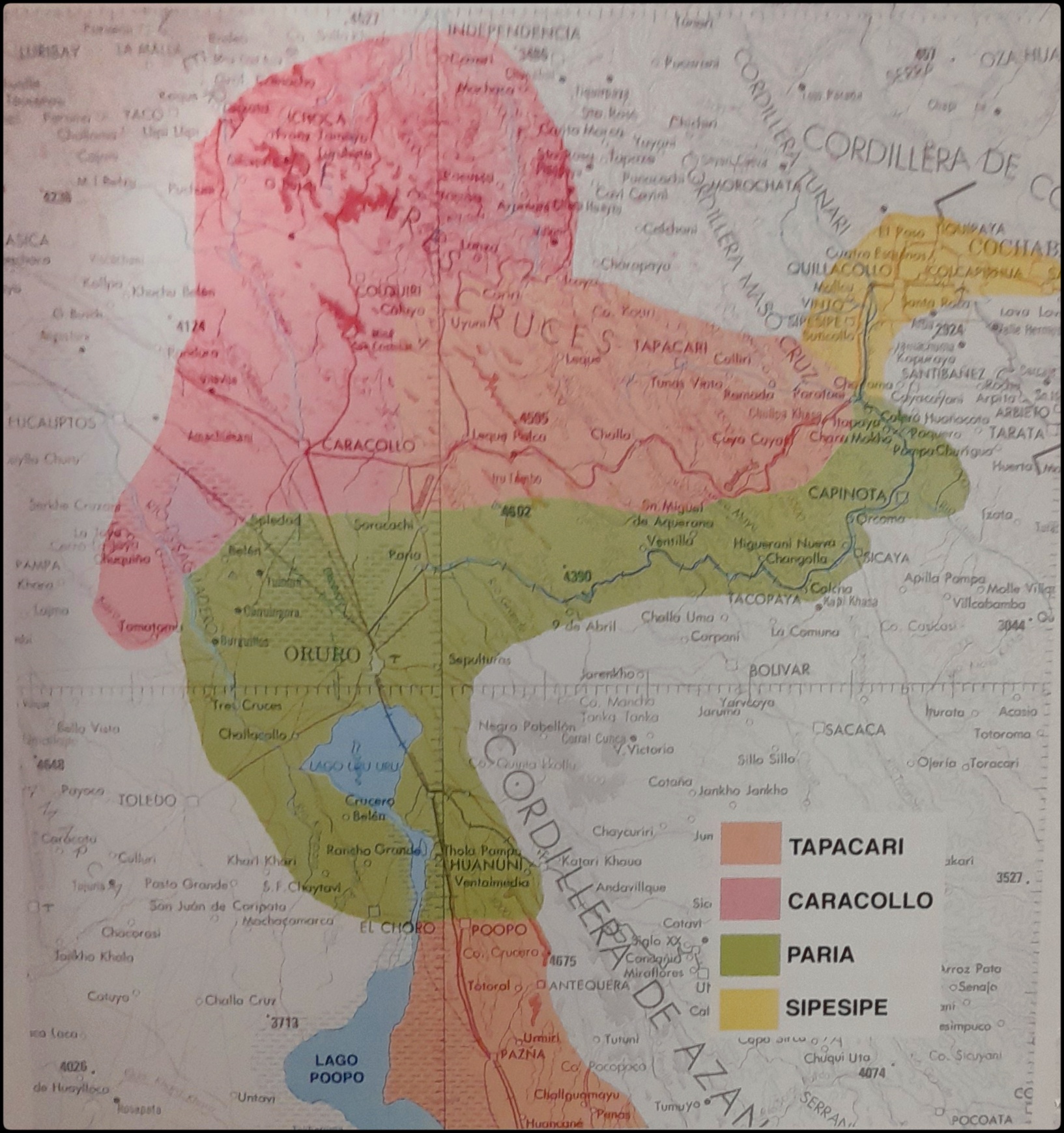

If the Toledo reforms of the 1570s affected the main towns or political centers of the Aymara lordships, the land compositions of the late 16th century aimed at reformulating the number of “islands” they had at the different ecological levels as well as the labor modalities of territorial exploitation: “The first visit and composition of lands (1593) had a foundational value, since it was through the oral testimonies provided by the ethnic authorities on the location, extension and boundaries of the territorial “islands” that the titles and rights of access to the colonial ethnic territories were defined for the first time.”11 The other destructuring effect of land composition ─besides the pressure exerted through the tribute and the mita mechanisms on the Indigenous people─, is that it produced a hard blow on economic balance and on the Indigenous communities´ self-sufficiency. Fiscal obligations had become unsustainable for the Indigenous population. The lands no longer met self-supporting purposes, but were strictly necessary for the productive surplus that the colonial system demanded to put it back on the market and, thus, participate in a monetary economy.12 The consequences of this social and economic disarticulation were dire. Many Indigenous people were forced to leave the “Pueblos Reales de Indios,” to free themselves from forced servitude, only to move on to another, leaving those who stayed in an unfavorable situation, as they had to take care of their own and other people’s debts and obligations.

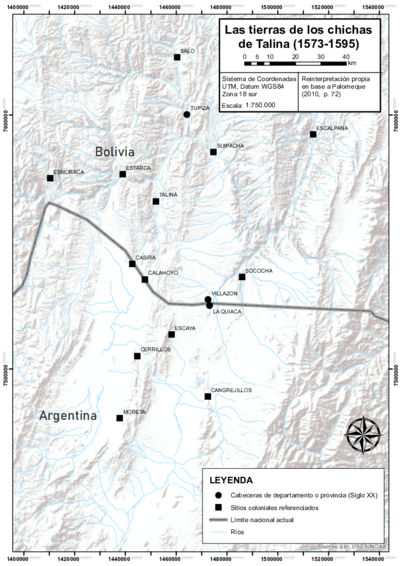

Finally, as was the case with the royal visits for censuses, the compositions attest to the new social transformations. For example, in the Aymara lordships of the Suras and the Chichas, as was the case with the censuses, the compositions ─which originated through the research carried out in the framework of a visit─ generated from two different perspectives (that of the group and that of the researcher/visitor) complex processes of pattern shifts in ethnic identification.13

Bibliography

Assadourian, Carlos Sempat, “Agricultura y Tenencia de la Tierra Antes y Después de la Conquista”. Población & Sociedad 12-13, no. 1 (2005): 3-56.

Carrera Quezada, Sergio. “Las Composiciones de Tierras en los Pueblos de Indios en dos Jurisdicciones Coloniales de la Huasteca, 1692-1720”. Estudios de Historia Novohispana no. 52 (2015): 29-50.

Del Río, Mercedes. Etnicidad, Territorialidad y Colonialismo en los Andes: Tradición y Cambio entre los Soras de los Siglos XVI y XVII. La Paz: Instituto de Estudios Bolivianos, 2005.

Glave, Luis. “Propiedad de la Tierra, Agricultura y Comercio, 1570-1700: el Gran Despojo.” In Compendio de Historia Económica del Perú. Tomo 2 Economía del Periodo Colonial Temprano, editado por Carlos Contreras, 313-446. Lima: Banco Central del Perú, 2020.

López-Beltrán, Clara. Estructura Económica de una Sociedad Colonial. Charcas en el Siglo XVII. La Paz, Bolivia: CERES, 1988.

Palomeque, Silvia. “Los Chichas y las Visitas Toledanas. Las Tierras de los Chichas de Talina (1573-1595).” Surandino Monográfico 1, no.2 (2010): 1-76.

Stern, Steve. Los Pueblos Indígenas del Perú y el Desafío de la Conquista Española. Huamanga hasta 1640. Madrid: Alianza, 1986.

Karen Spalding, Huarochiri. An Andean Society Under Inca and Spanish Rule (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1984). ↩︎

Carrera Quezada, Sergio, “Las Composiciones de Tierras en los Pueblos de Indios en dos Jurisdicciones Coloniales de la Huasteca, 1692-1720,” Estudios de Historia Novohispana no. 52 (2015): 29-50. ↩︎

Carrera Quezada, “Las Composiciones de Tierras en los Pueblos de Indios en dos Jurisdicciones Coloniales de la Huasteca, 1692-1720,” 31. ↩︎

Carlos S. Assadourian, “Agriculture and Land Tenure Before and After the Conquest,” Population & Society 12-13, no. 1 (2005): 3-56. ↩︎

Carrera Quezada, “Las Composiciones de Tierras en los Pueblos de Indios en dos Jurisdicciones Coloniales de la Huasteca, 1692-1720,” 31-32. ↩︎

Assadourian, “Agricultura y Tenencia de la Tierra Antes y Después de la Conquista,” 49. ↩︎

Luis Glave, “Propiedad de la Tierra, Agricultura y Comercio, 1570-1700: el Gran Despojo,” in Compendio de Historia Económica del Perú. Economía del Periódico Colonial Temprano, ed. Carlos Contreras (Lima: Banco Central del Perú, 2020), 313-446. ↩︎

Steve Stern, Los Pueblos Indígenas del Perú y el Desafío de la Conquista Española. Huamanga hasta 1640 (Madrid: Alianza, 1986). ↩︎

Stern, Los Pueblos Indígenas del Perú y el Desafío de la Conquista Española. Huamanga hasta 1640, 188. ↩︎

Stern, Los Pueblos Indígenas del Perú y el Desafío de la Conquista Española. Huamanga hasta 1640, 214; Glave, “Propiedad de la Tierra, Agricultura y Comercio, 1570-1700: el Gran Despojo”. ↩︎

Mercedes Del Río, Etnicidad, Territorialidad y Colonialismo en los Andes: Tradición y Cambio entre los Soras de los Siglos XVI y XVII (La Paz: Instituto de Estudios Bolivianos, 2005), 287. ↩︎

Clara López-Beltrán, Estructura Económica de una Sociedad Colonial. Charcas en el Siglo XVII (La Paz: CERES, 1988), 172-173. ↩︎

Del Río, Etnicidad, Territorialidad y Colonialismo en los Andes: Tradición y Cambio entre los Soras de los Siglos XVI y XVII; Silvia Palomeque, “Los Chichas y las Visitas Toledanas. Las Tierras de los Chichas de Talina (1573-1595),” Surandino Monográfico 1, no.2 (2010): 1-76. ↩︎