Abstract

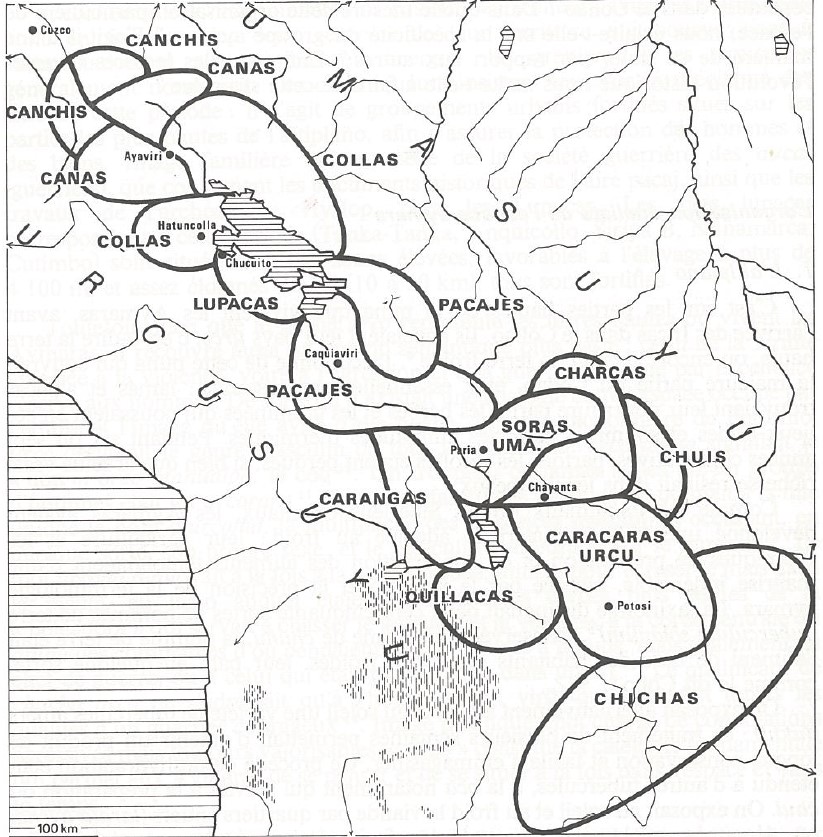

In the context of the Spanish colonization of the Tawantinsuyu Inca state, and more specifically as of the 1530s onwards, mita was the term used to refer to the expropriation of Indigenous labor in the form of mandatory, shift-based labor services. Though in the first decades following the conquest the Spanish colonizers arbitrarily used and abused this system, as of Viceroy Toledo´s reforms in the 1570s, the mita became an institution of the colonial state aimed primarily at lowering production costs in the silver mines of Potosí. The Potosí mita mainly affected the Aymara lordships of the Qullasuyu, and imposed on the Indigenous economies the role of subsidizing the Indigenous labor force used by the Spaniards.

The term “mita” stems from Qhishwa mit’a, which means “turn” —work that is done or distributed in shifts. Under the Inca state, this term was also used to refer to the system of mandatory works that men of legal age had to perform every so often in the construction or maintenance of public works or in agriculture on Inca state lands. The Spaniards took up this system (under a similar term, “mita”), but adjusted and repurposed its original goals.

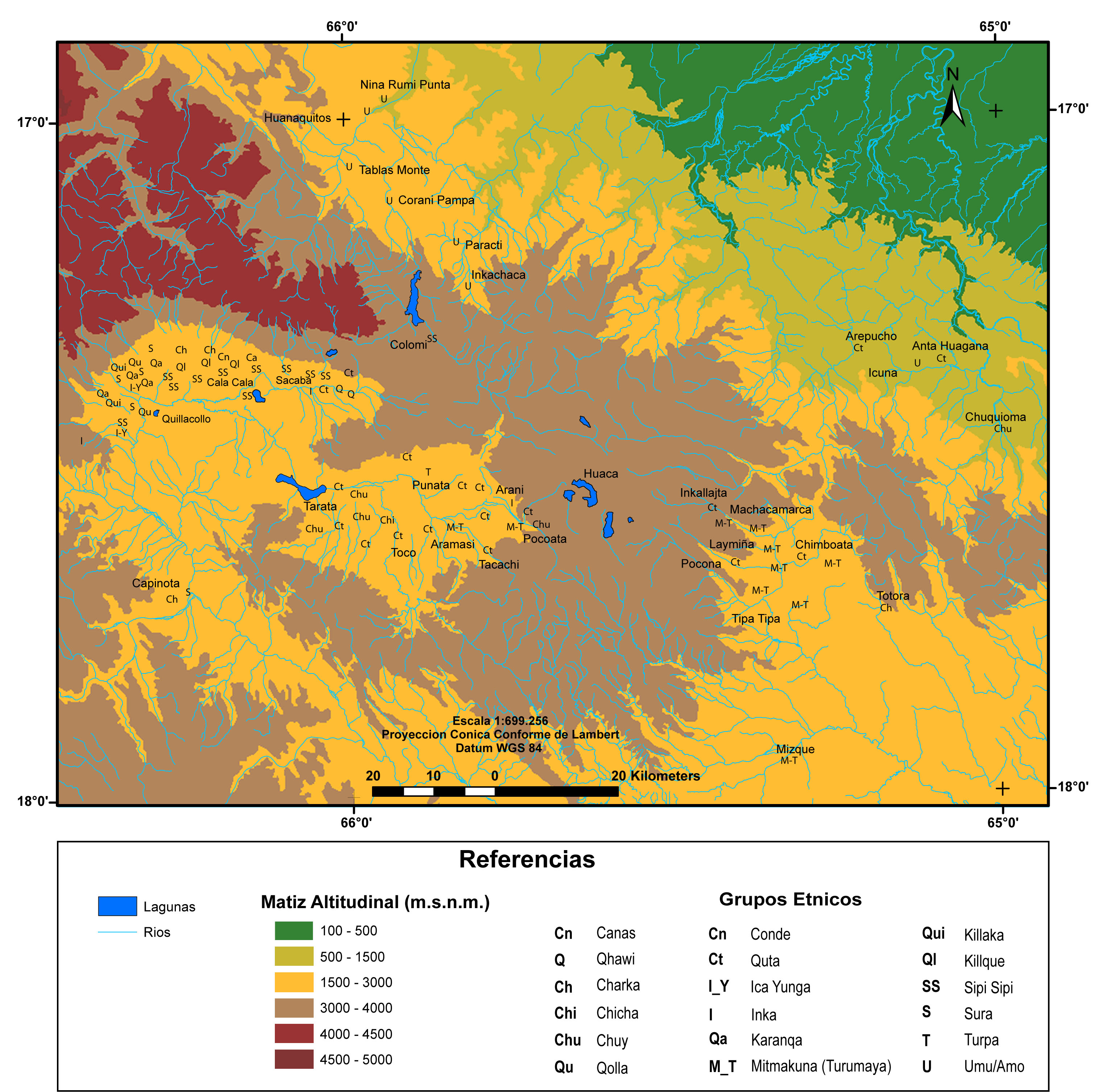

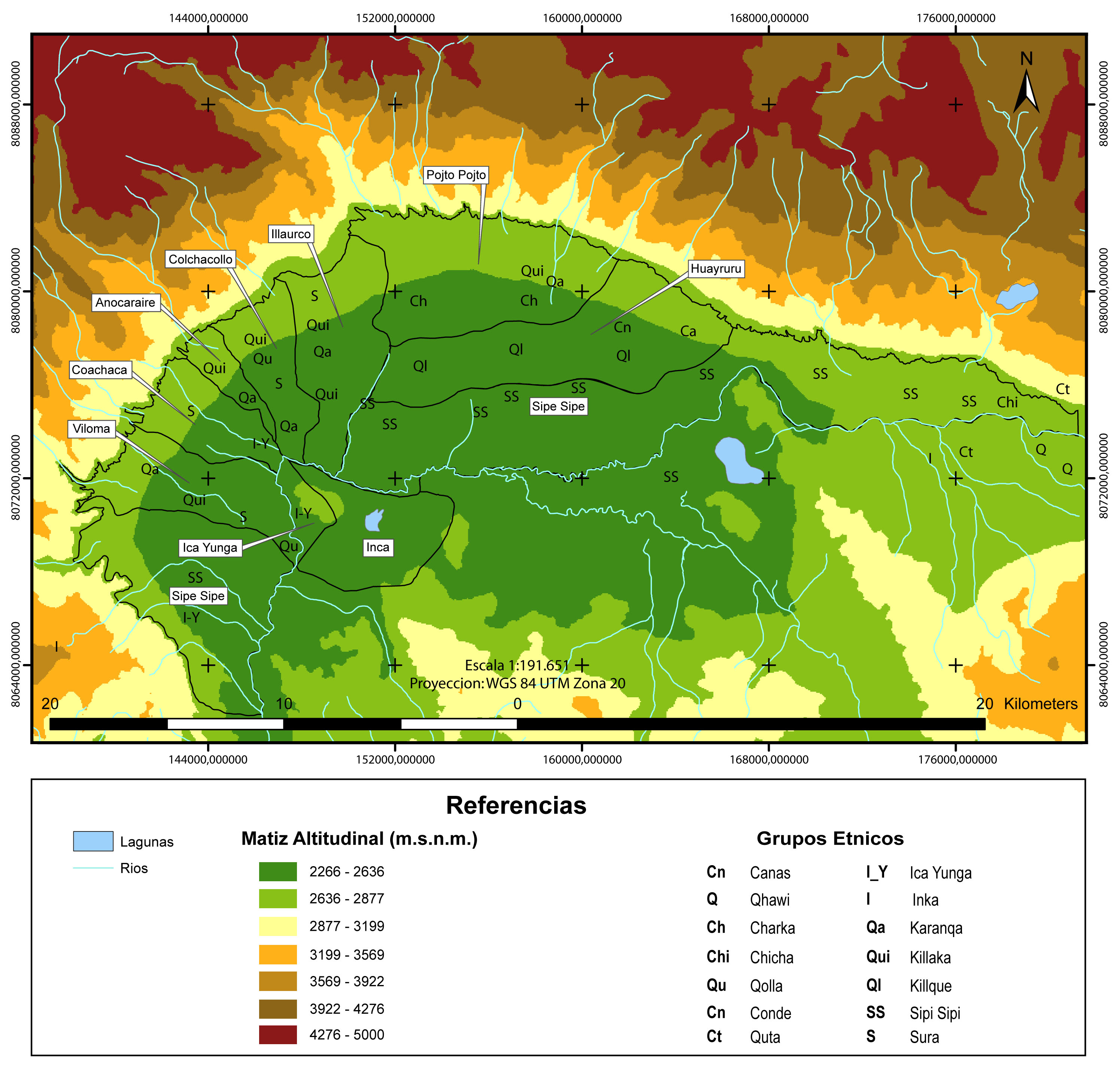

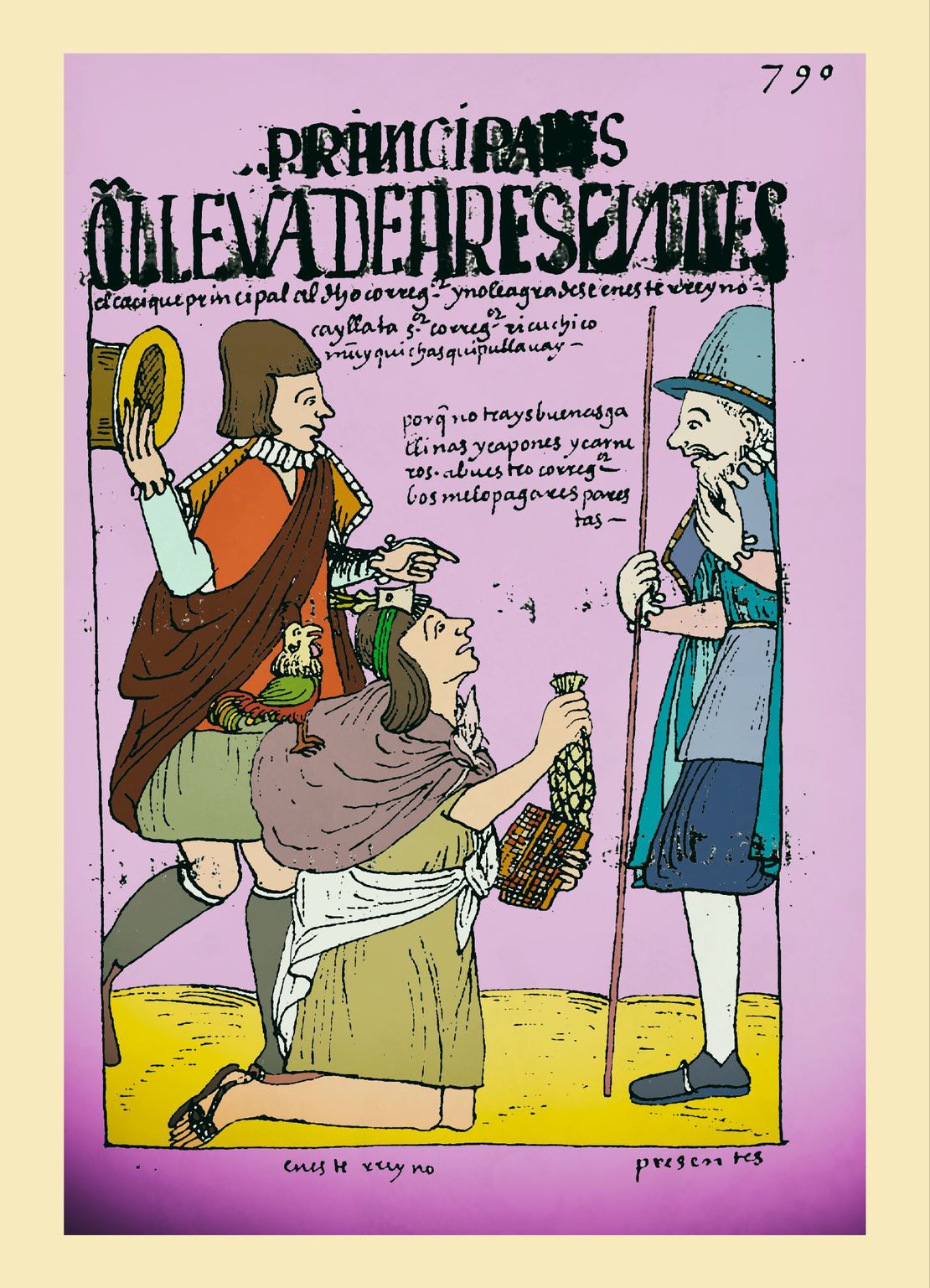

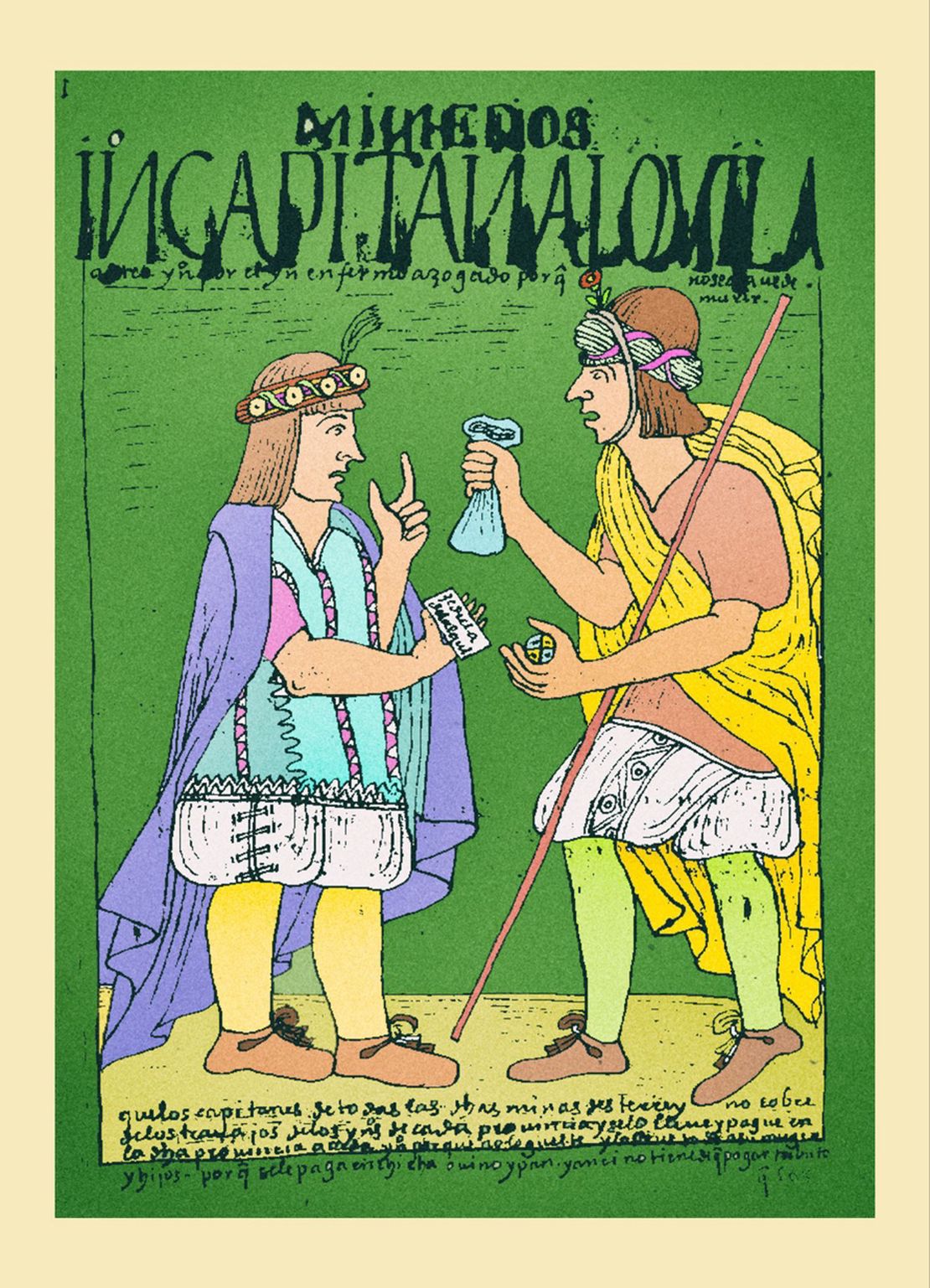

At first, in the context of the encomienda, the Spaniards benefitted from this practice to exploit Indigenous labor for personal services and for the advantage of their family enterprises.1 But, starting in the 1570s and within the Toledo Reforms framework, this shift-based and mandatory labor structure became an institution imposed by the colonial state and aimed chiefly at subsidizing the production costs of the silver mines of Potosí. It is likely that the Toledo mita model may have been based on labor recruitment carried out by the Inca state in the Cochabamba valleys MULTI-ETHNIC TERRITORY under INCA DIRECT RULE: THE CENTRAL AND UPPER VALLEYS OF COCHABAMBA in the 1530s since an identical number of mitayos —around 13,500—, was established for the Potosí mines through the organization of 16 “mita captaincies”, involving authorities of the Aymara lordships to recruit mitayos from their respective jurisdictions.2

With the aims of strengthening and institutionalizing the presence of the colonial state, and reactivating silver production in the mines of Potosí, the Toledo Reforms sought to restrain the power of the encomenderos, renew the technology and infrastructure of the mining industry in Potosí, assemble the Indigenous populations in concentrated settlements —Reducciones— for a more direct and effective control; and rationalize the tax regime to which the Indians were subjected to include the monetization of tributeand the mandatory labor services in the mines of Potosí, i.e. the mita. These reforms made it possible —at least for the first 30 years—, to secure a stable stock of labor supply in the Potosí mines and to bring silver production to its peak in the 1590s.

The concentration of scattered villages into settlements called “Pueblos Reales de Indios” orReducciones, the monetization of tribute and the institutionalization of the mita were the reforms that most profoundly affected the political structures and the territorial, social and economic organization of Andean societies, causing the displacement and fragmentation of the great Aymara lordships of the Qullasuyu. Conceived as a rationalization of the colonial administration of territories and populations, and as a systematization of the mechanisms for the extraction of surplus and labor, these three measures were closely intertwined, with the reducciones being the key piece in this structure. Indeed, the reducciones made it possible to control the “Indians” and evangelize them in a more orderly manner, collect tribute more systematically, and recruit the workers on duty for the mita more efficiently.

Indians relocated to a “Pueblo Real de Indios” were registered as residents of the village and, as such, had corporate rights to the lands around that village. In Toledo´s model, access to those lands would secure not only their subsistence but also surplus production. In exchange for the right to the land, they incurred tax obligations: a cash tax to be paid by each “native” or “originario” —fit men between 18 and 50 years old registered in a reducción or settlement—, and the mandatory labor service to be performed in the mines of Potosí from time to time.

The Toledo mita structure was organized in three groups per year and the mitayos —mita workers— would work one week and rest for two weeks. The mitayos traveled with their families carrying most of the basic foodstuff they would need for those months. Most of the little money they earned for their work in the mine was used to pay the tribute they owed to the colonial state.3 To cover the expenses of their stay in the city, the mitayos would sell their labor as mingas —“voluntary” wage earners— during their weeks off or sell at the market a small portion of the ore they had extracted and were “allowed” to keep.4 Such unofficial practices, ignored by colonial officials, were consolidated over time, generating a significant gap between the actual functioning of the mita and the legal mita structures. In any case, a mitayo would cost mine owners about a third of the cost of a “voluntary” minga wage-earner.

The mita represented an enormous subsidy to the mining companies that received it. Although mitayos amounted only to 30% of the labor force in Potosí in the late sixteenth century, their work for wages lower than what they obtained through mingas significantly reduced the cost of silver production. For the “originarios” or “natives,” their families and the Indigenous communities in the reducciones as a whole, the Potosí mita stood as a heavy burden. The money that the mitayos earned in Potosí did not go to their communities, but was directly or indirectly transferred to Spanish hands. In addition, by covering the reproduction of the mita labor force, the Indigenous communities fulfilled the function of subsidizing the Spanish mining economy.5

In summary, the Toledo reforms did not imply massive land dispossessions, but rather profound reconfigurations of Indigenous territories with the objective of greater control and more efficient expropriation of the Indigenous surplus and labor force by the colonial state. However, the creation of “Pueblos Reales de Indios” as segregated and self-sufficient Indigenous communities was not a sustainable project in the face of the market forces that these same reforms unleashed, the generalized crisis that characterized the 17th century and the different forms of Indigenous resistance. One of these forms was the flight of “native” taxpayers/mitayos from the reducciones.

The 17th century is generally characterized as the period of greatest crisis and decline of the Spanish empire.6 Between the 1630s and 1730s, the economic space articulated around Potosí witnessed a strong demographic crisis, a steady decline in the volume of silver production, and the weakening of colonial state power. Given the inertia of a debilitated state, the actual forms of extraction of surplus and Indigenous labor were defined by local actors and power dynamics.

The fall in mining production was due not only to the decreasing quality of the minerals extracted, but also to the demographic crisis, which was —in turn— not only due to epidemics and diseases, but also to the massive flight of taxpayers/mitayos from the reducciones where they were “native” residents. When they fled, they ceased to be “natives” and were freed from their taxpaying/mitaya obligations. They then became “outsiders” who did not belong to any taxpaying category. Data from the late 17th century suggest that —in the region subject to the Potosí mita—, almost half of the Indigenous population did not comply with their tribute and mita obligations.7 It was not until the mid-18th century that outsiders were included in an expanded Indigenous tribute COLONIAL LEGISLATION AS FRAMEWORK FOR DISPOSSESSIONS IN THE CENTRAL ANDES: THE INDIGENOUS TRIBUTE, 1730s - 1820s .

Faced with the demographic crisis, the colonial state was forced to significantly reduce the required mita quota, but the actual number of mitayos in the mines was always less than required. As the number of mitayos decreased, the mechanisms of expropriation and labor exploitation increased. Disobeying official regulations, mine owners modified the organization of labor by imposing new forms of exploitation. One of these innovations was the assignment of fixed tasks that mitayos had to perform without leaving the mine or receiving payment until completed. Another unofficial practice was the commutation of the mita service for a cash payment to the mine owner. Although it was assumed that the money would be used to pay another worker, some owners would prefer to keep the money, turning commutation payments into a convenient rent.8

Thus, over the years, the actual ways in which the mita functioned increasingly differed from the legal regulations of the colonial state. In this context, by the end of the 18th century, mitayos remained in Potosí for a full year and were forced to go into debt by buying in the market and resorting to informal mining (kajcheo) or other activities to pay their debts.9 The higher levels of expropriation/labor exploitation of the mita system implied greater market participation and greater pressure on Indigenous communities to subsidize mining production.

These “informal” practices and “illegal” mechanisms of labor expropriation/exploitation established throughout the 18th century, allowed Potosí mining to double its production between 1740 and 1790 with a reduced labor force. By the 1790s, mita labor accounted for about 50% of the labor force in the Potosí mines and constituted the prevalent production relationship.10 In short, in the 2 centuries of colonial domination, the percentage of compulsory mitayo labor - relative to “voluntary” wage labor - had increased —from 10% in the 1550s to 30% in the 1570s, and 50% in the 1790s—, and the mechanisms of expropriation/labor exploitation had been consolidated and hardened. The mita was legally abolished in the 19th century in the context of the wars of independence.

Bibliography consulted

Abercrombie, Thomas. “Q’ajchas and la Plebe in Rebellion: Carnival vs Lent in Eighteenth Century Potosi.” Journal of Latina American Anthropology 2, no.1 (1996): 62-111.

Andrien, Kenneth. Crisis and Decadence: The Viceroyalty of Peru in the Seventeenth Century. Lima: Banco Central de Reserva del Perú, 2011.

Assadourian, Carlos Sempat, “La Producción de la Mercancía Dinero en la Formación del Mercado Interno Colonial”. Economics, 1(2), 9-56. (1979).

Bakewell, P. Miners of the Red Mountain: Indian Labor at Potosi 1545-1650. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1984.

Larson, Brooke. Colonialism and Agrarian Transformation in Bolivia: Cochabamba 1550-1990. La Paz, Bolivia: Vicepresidencia del Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia, 2017.Presta, Ana María. Encomienda, Family and Business in Colonial Charcas. Los Encomenderos de La Plata 1550 - 1600. Sucre: Archivo y Biblioteca Nacionales de Bolivia, 2014.

Sánchez-Albornoz, Nicolás. Indians and Tributes in Upper Peru. Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, 1978.

Tandeter, Enrique. Coacción y Mercado: La Minería de la Plata en el Potosí Colonial, 1629 - 1826. Cusco: Centro de Estudios Regionales Andinos Bartolomé de las Casas, 1992.

Wachtel, Nathan. “The Mitimas of the Cochabamba Valley: The Colonization Policy of Huayna Capac.” In The Inca and Aztec States: 1400 - 1800. Anthropology and History, edited by Geroge Collier, 199-235. New York: Academic Press, 1982.

Ana María Presta, *Encomienda, Family and Business in Colonial Charcas. Los Encomenderos de La Plata 1550 - 1600, (*Sucre: Archivo y Biblioteca Nacionales de Bolivia, 2014). ↩︎

Nathan Wachtel, “The Mitimas of the Cochabamba Valley: The Colonization Policy of Huayna Capac,” in The Inca and Aztec States: 1400 - 1800. Anthropology and History, ed. George Collier (New York: Academic Press), 199-235. ↩︎

Carlos S. Assadourian, “The Production of the Commodity Money in the Formation of the Colonial Internal Market,” Economics, 1(2), 9-56. (1979): 36. ↩︎

Enrique Tandeter, Coacción y Mercado: La Minería de la Plata en el Potosí Colonial, 1629 - 1826 (Cusco: Centro de Estudios Regionales Andinos Bartolomé de las Casas, 1992). ↩︎

Assadourian, “The Production of the Commodity Money in the Formation of the Colonial Internal Market.” Tandeter, Coercion and Market: Silver Mining in Colonial Potosí, 1629 - 1826. ↩︎

Kenneth Andrien, Crisis and Decadence: The Viceroyalty of Peru in the Seventeenth Century (Lima: Banco Central de Reserva del Perú, 2011). ↩︎

Nicolás Sánchez-Albornoz, *Indios y Tributos en el Alto Perú (*Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, 1978). ↩︎

Tandeter, Coercion and Market: Silver Mining in Colonial Potosí, 1629 - 1826. ↩︎

Tandeter, Coercion and Market: Silver Mining in Colonial Potosi, 1629 - 1826; Thomas Abercrombie, “Q´ajchas and la Plebe in Rebellion: Carnival vs Lent in Eighteenth Century Potosí.” Journal of Latina American Anthropology 2, no.1 (1996): 62-111. ↩︎

Tandeter, Coercion and Market: Silver Mining in Colonial Potosí, 1629 - 1826. ↩︎

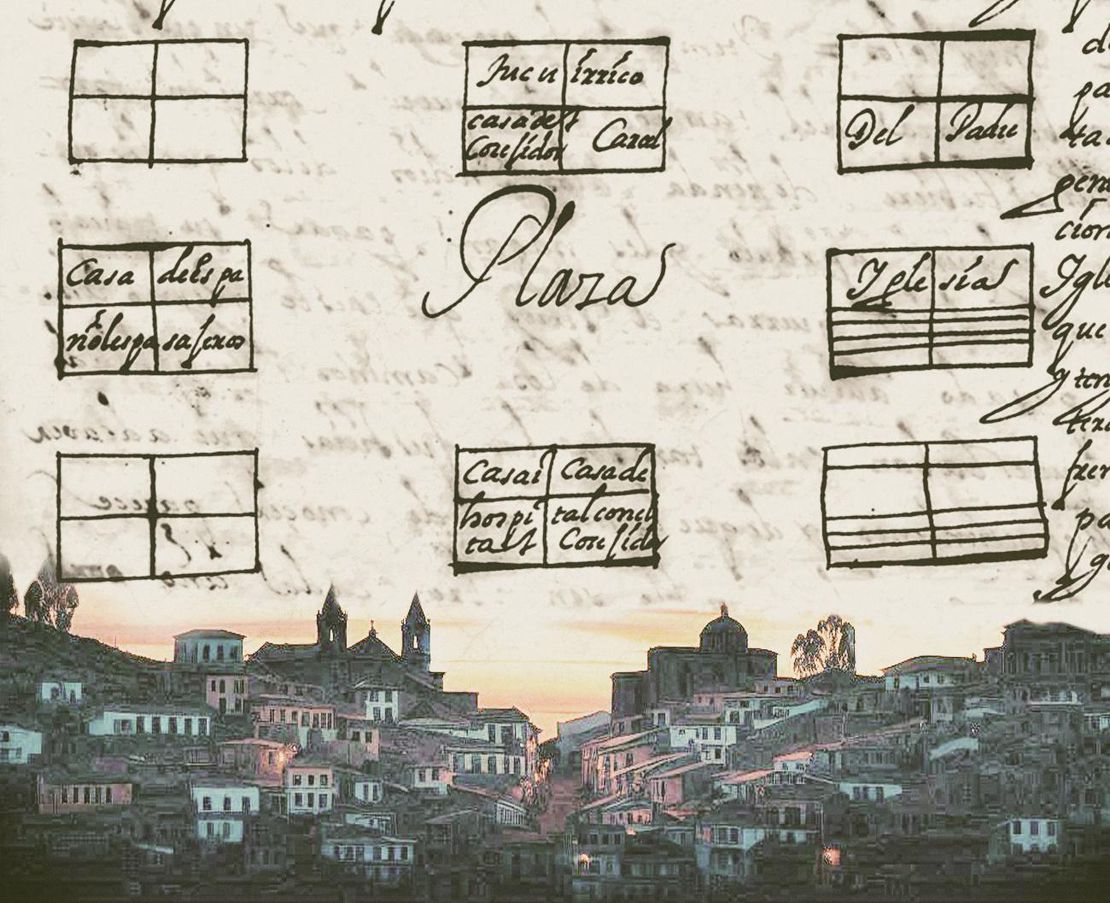

![Cieza de León, Pedro \[1553\]. *Potosí.* Source: Paula Zagalsky. *Obedecer, negociar y resistir. Tributo y mita indígena en Potosí, siglos XVI y XVII.* (Lima: Banco Central de Reserva del Perú-Instituto de Estudios Peruano, 2023). Digitally intervened by Mauricio Sánchez Patzy.](/images/content/TL005Mita/image1_hu9f012819d87d9b36a676270245f62bea_284958_1110x0_resize_q80_lanczos.jpg)