Abstract

Beginning in the 16th century with the Spanish conquest of Tawantinsuyu, the Inca state, the Indigenous tribute´s history is long, complex, and extends beyond the colonial period until the end of the 19th century. In the early decades (1530s - 1560s), the initial Indigenous tribute was featured by arbitrary payments in kind and labor services to be paid collectively. After the significant reforms implemented by Viceroy Toledo in the 1570s, the tax regime imposed on the Indigenous peoples of Tawantinsuyu, and particularly on the Aymara lordships of Qullasuyu took a radical turn and was defined as an individual tax to be paid in currency. The whole concept of tribute “represented a great change for the members of the Andean society, used to the allocation of levies or tasks that were then allotted by the kurakas, and they fought accordingly"1 . The tribute monetization and individualization took on an unprecedented weight for the Andean populations.

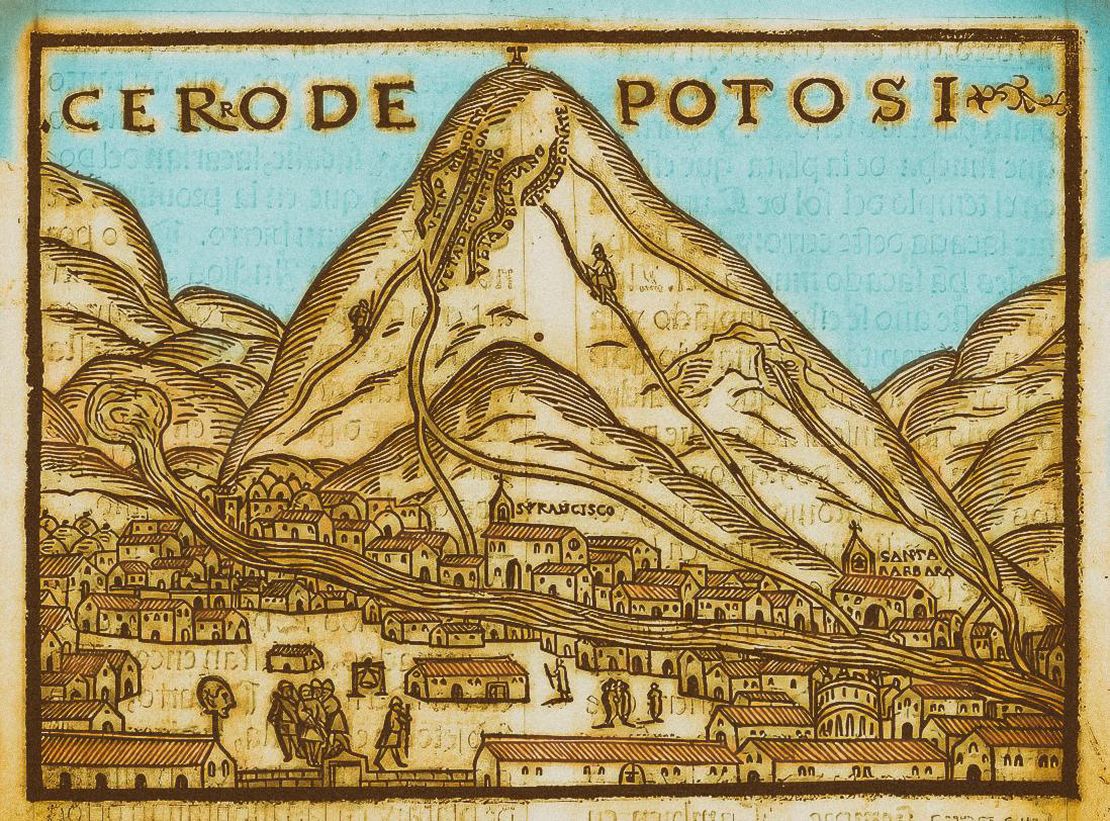

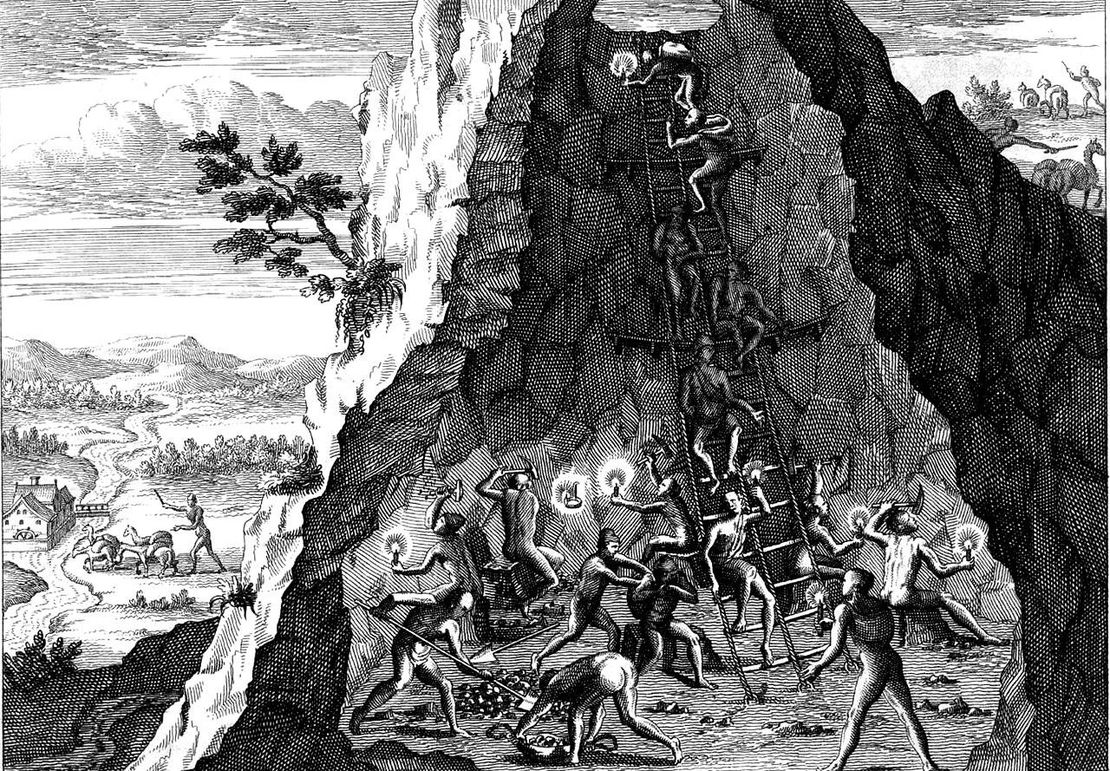

Toledo’s reforms responded to the Spanish crown´s financial needs and the king’s concern about the decrease in silver extracted from Potosí, the clear signs of the native population´s decline, the threat of millenarian movements in the highlands of Perú and the danger posed by the encomenderos whose power was consolidating in parallel and independent of the crown. In this context, Toledo´s reforms had the following main objectives: 1) to strengthen and institutionalize the presence of the colonial state, 2) to consolidate its role as an agent of metropolitan interests and as a the direct claimant of the natives´ resources, and 3) to relaunch and increase the production of the Potosí silver mines. To this end, the political-administrative division of the viceroyalty was institutionalized, and the power and privileges of encomenderos were limited by restricting the encomienda concessions, and imposing state officials as intermediaries between the encomenderos and their taxpayers. The Indigenous tax system was systematized and rearranged, the mita system of Potosí was organized —forced labor by shifts of Indigenous taxpayers—, the scattered Indigenous populations were assembled in concentrated settlements —Reducciones—, local Indigenous mining technology was replaced by quicksilver technology (with mercury from the Huancavelica mines), and important investments were made in mining industry infrastructure. These reforms succeeded, at least during the first 30 years, in ensuring a stable labor force in the Potosí mines, bringing silver production to its peak in the 1590s and securing a significant increase in the amount of Indigenous tribute collected for the colonial state.

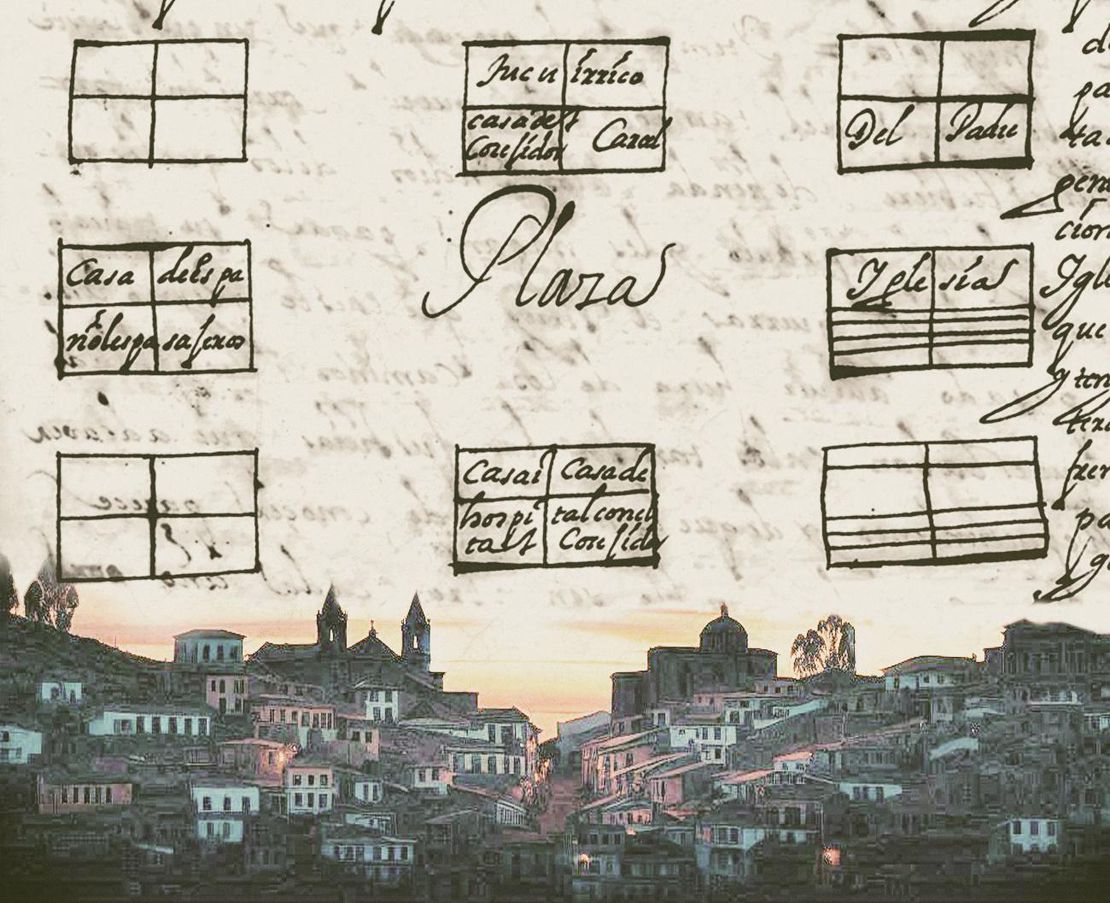

Conceived as a rationalization of the colonial administration of territories and populations, and as a systematization of the mechanisms for the extraction of surplus and indigenous labor, the Toledo reforms molded a set of interrelated measures. Among these stand the articulation and concentration of scattered villages in core or key towns, “Pueblos Reales de Indios” or Reducciones, the institutionalization of the forced labor system called mita, and the monetization of the Indigenous tribute, with the Reducciones taking on a central role in such articulation.

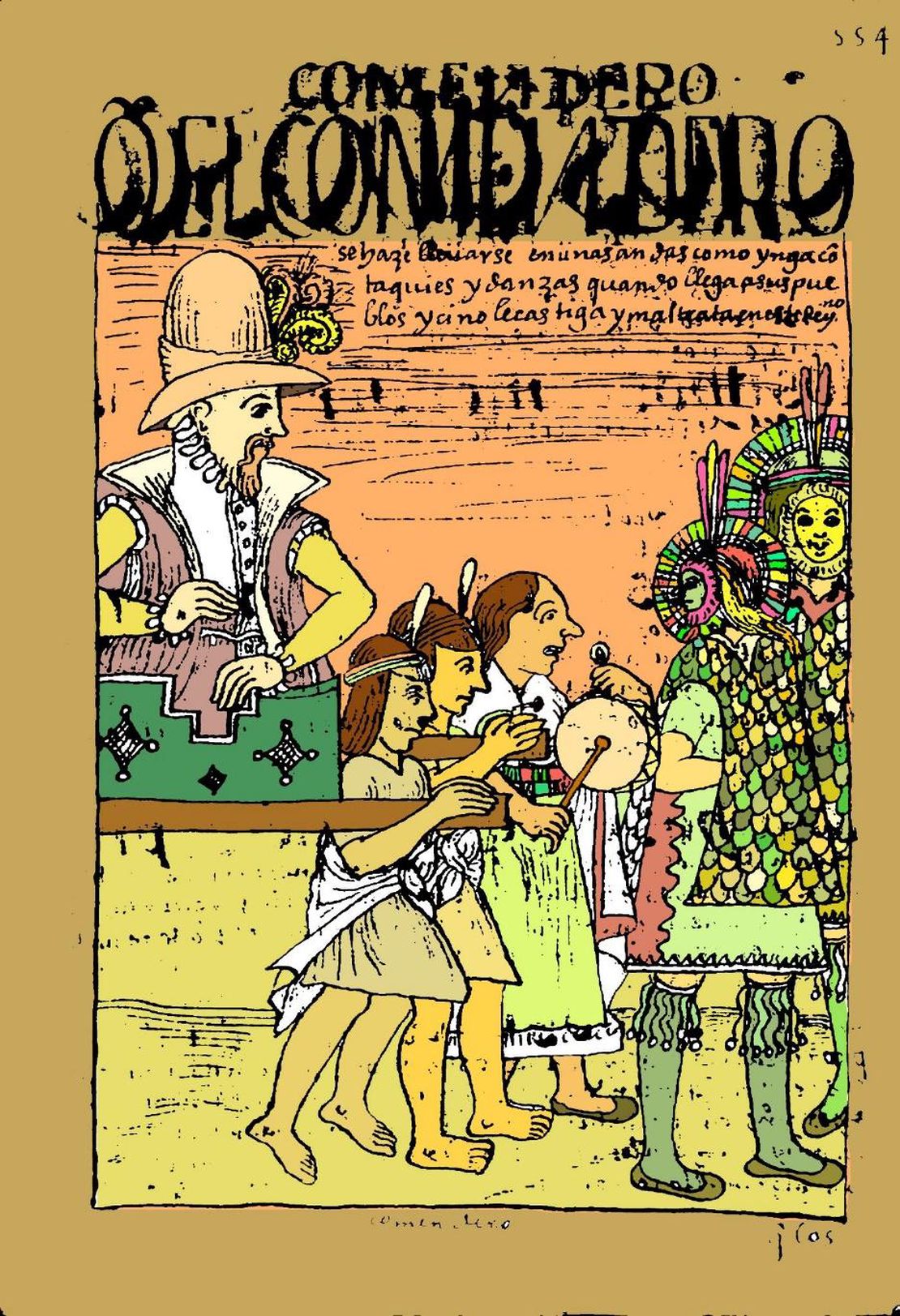

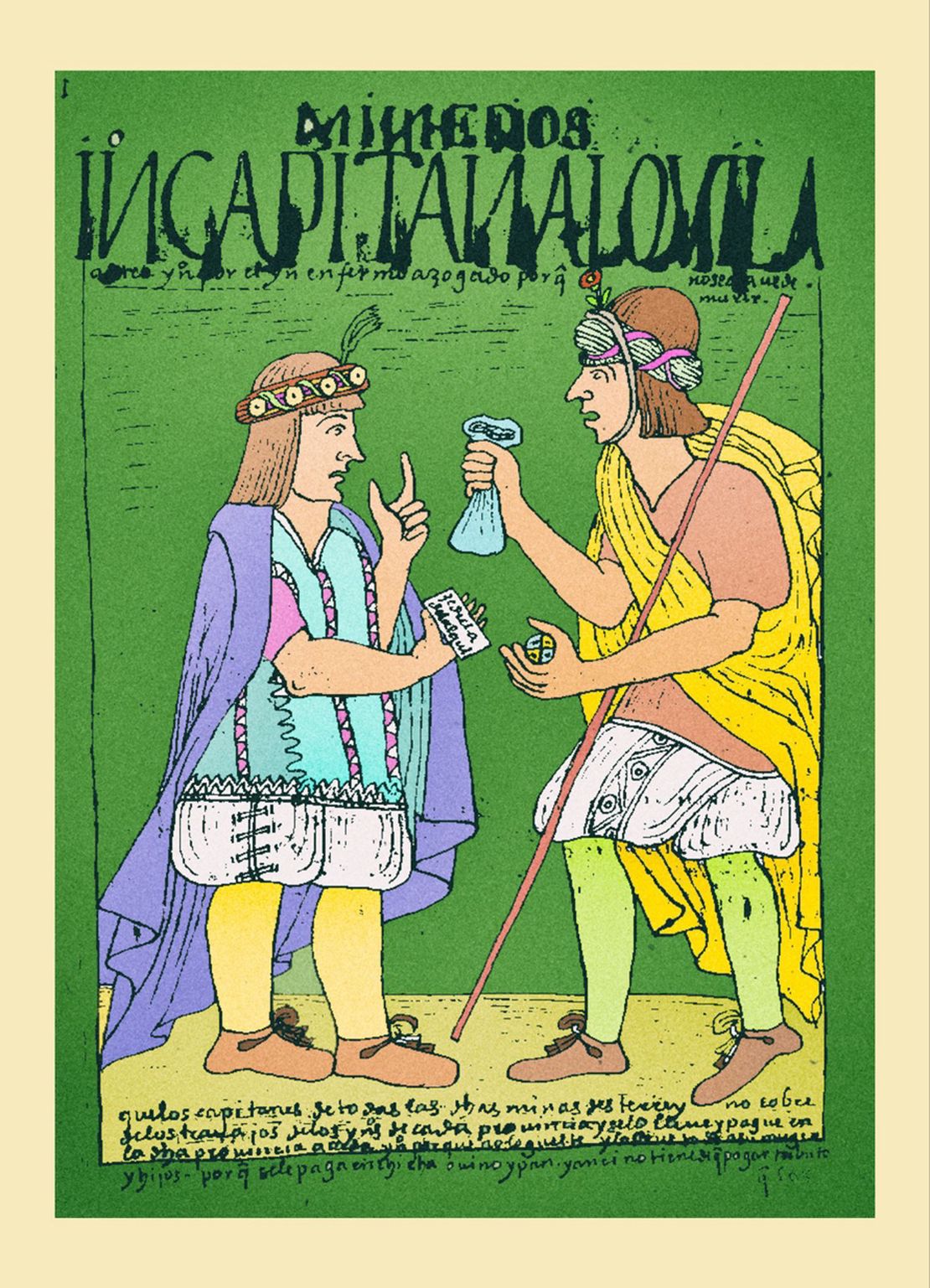

Indeed, the concentration of the Indigenous population in a fixed and rationally designed settlement allowed for more orderly governance, more systematic evangelization and, above all, more efficient tax collection and labor recruitment. These “Pueblos Reales de Indios” were governed by a set of both Spanish and Indigenous authorities. The kurakas —Indigenous authorities also called caciques by the Spanish— were appointed officials, released from tribute obligations, and paid by the colonial state to collect Indigenous tribute and recruit labor force for the mita under the close supervision of Spanish parish priests and corregidores.

In short, it was only under the government of Viceroy Toledo (1569 - 1581) that the legal and institutional foundations were laid for the consolidation of the colonial order in the Andes in general, and in the Qullasuyu provinces in particular, given the importance of the silver mines of Potosi. Toledo’s reforms were preceded by a thorough census, called visita general, which consisted of a meticulous field inspection to develop a new tax regulation, a specific count of the Indigenous and taxpaying population, and a detailed record of the mechanisms and institutions that the Inca state had established to capture surpluses and mobilize labor.

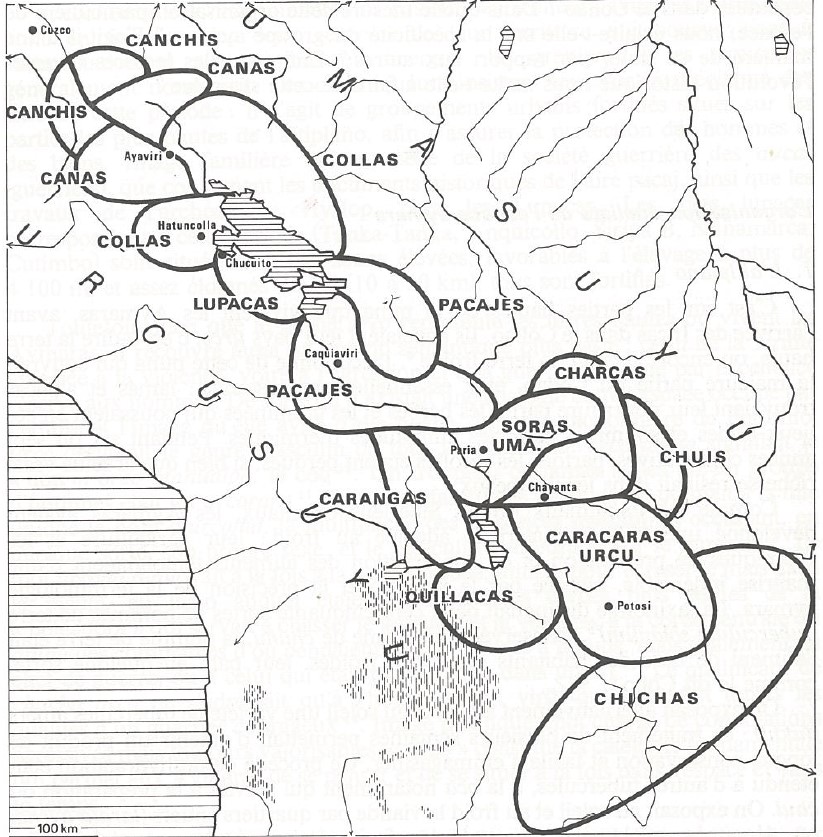

In this “General Visit,” which took five years to complete (1570-1575), “the Indigenous residents of the territory between Quito (Ecuador), Tarija and Lípez (Bolivia) were registered, documenting each community and each family in detail. Adult male taxpayers between 18 and 50 years of age and original members of an ayllu —a group of nested kinship groups— AYMARA POLITIES of THE QULLASUYU in the 16th CENTURY were registered in the tax log. Exceptions were made for the disabled, native chiefs —along with their eldest sons in their capacity as nobles—, and village mayors (throughout the term of their functions). The annual individual tribute was set between 2.5 and 10 pesos, according to the productive capacity of the area and the ethnic group, payable in two installments: one at San Juan and the other one at Christmas.” Once the registration was done, “the amount was fixed until the next visit, disregarding the dead and those who had become of age to pay taxes.”2

Adjustments were made to the tax regime based on the information gathered during this “General Visit.” In the context of the “Indian Reducciones”, the category of “Indian taxpayers” corresponded to fit Indigenous men between 18 and 50 years old **originating from the ayllu ***—that is, who resided in the Reducciones territory where they had rebuilt the ayllu organization— and, as such, had the right to cultivate the land and use the resources of that territory.

As authorities of the ayllus reconstituted in the Reducción, the kurakas were responsible for collecting and delivering the corresponding amounts to the taxpayers of their respective ayllus. Those Indians who were not registered as Reducción residents COLONIAL LEGISLATIONS AS FRAMEWORK FOR DISPOSSESSIONS IN THE CENTRAL ANDES: THE “REDUCCIONES” OR “PUEBLOS REALES DE INDIOS” and as originating from one of their ayllus, did not have those rights, were not under the authority of any kuraka and, therefore, did not belong to the category of taxpaying Indians, and did not pay tribute nor were they recruited for the mita. In the case of the “yanaconas Indians” —Indians who were under the service of Spanish landowners—, they depended on the latter´s authority and were not linked to any ayllu or Reducción, the amount of tribute was lower, they were not subject to the mita and, in general, the tribute was paid by their employer.

It is important to point out that, as a surplus collection mechanism, the Indigenous tribute depended on the resources and the possibilities and capacities of the taxpayers to produce that surplus in a constant and sustainable manner, that is, maintaining the conditions that secured self-sufficiency and reproduction. Being part of a state society, the Tawantinsuyu “Indians”, and in particular the Aymara lordships of the Qullasuyu, not only produced considerable surpluses, but also had their own institutions that regulated their transfer and the provision of services for the benefit of a central state. The challenge for the colonial state was to maintain that surplus-producing capacity, and at the same time to make the necessary changes to guarantee the colonial state’s control over the Indigenous people that the conquest had turned into subjects of the Spanish crown.3

It was thus a delicate balance that colonial institutions and practices failed to maintain, giving rise to different forms of resistance —either to evade tribute or to defend the resources and conditions that made possible their self-sufficiency, or at least their subsistence. The modifications in the terms of Indigenous tribute in the 17th COLONIAL LEGISLATION AS THE FRAMEWORK FOR DISPOSSESSIONS IN THE CENTRAL ANDES: THE INDIGENOUS TRIBUTE, 1630s -1720s and 18th COLONIAL LEGISLATION AS FRAMEWORK FOR DISPOSSESSIONS IN THE CENTRAL ANDES: THE INDIGENOUS TRIBUTE, 1730s - 1820s centuries can be understood as responses to the different forms of resistance. However, what remained unchanged was the general trend towards an increasing monetization and individualization of tribute that progressively integrated the Indigenous into the market, fragmented the ethnic lordships and eroded their material conditions of reproduction. Despite all this, the Indigenous tribute constituted an important source of income for the functioning of the colonial state over the course of three centuries, and even of the republican state in its first 50 years.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Barragán, Rossana and Paula Zagalsky, eds. Potosi in the Global Silver Age (1600 -19thth Centuries). Leiden: Brill, 2023

Larson, Brooke. Colonialism and Agrarian Transformation in Bolivia: Cochabamba 1550-1990. La Paz: Vicepresidencia del Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia, 2017.

López, Clara. Economic Structure of a Colonial Society. Charcas en el Siglo XVII. La Paz: Centro de Estudios de la Realidad Económica y Social, 1988.

Sánchez Albornoz, Nicolás. Indians and Tributes in Upper Peru. Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, 1978.

Platt, Tristan. “On the Pre-Toledan Tax System in Upper Peru.” Advances 1, (1978): 33-46.

Spalding, Karen. Huarochirí. An Andean Society Under Inca and Spanish Rule. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1984.

Karen Spalding, Huarochiri. An Andean Society under Inca and Spanish Rule (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1984), 159 (own translation). ↩︎

Clara López Beltrán, Estructura Económica de una Sociedad Colonial (La Paz: CERES, 1988), 143-144. ↩︎

Brooke Larson, Colonialism and Agrarian Transformation in Bolivia: Cochabamba 1550-1990 (La Paz: Vicepresidencia del Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia, 2017). ↩︎

](/images/content/TL004Tributo/image1_hu08927b64e8331532022bf0dd5cd194c0_461158_1110x0_resize_q80_lanczos.jpg)