Abstract

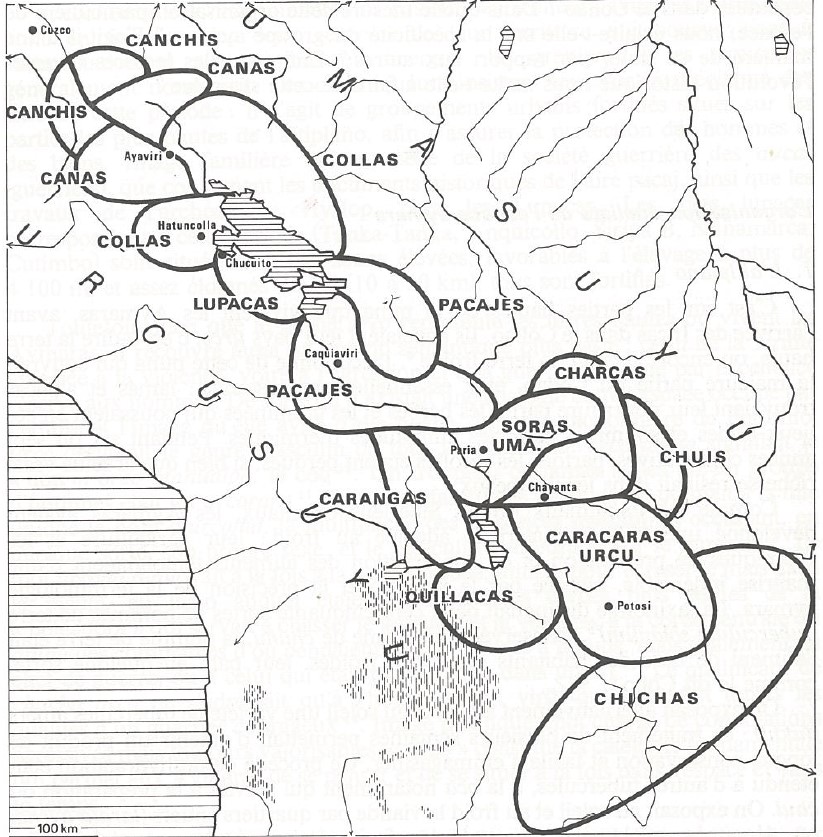

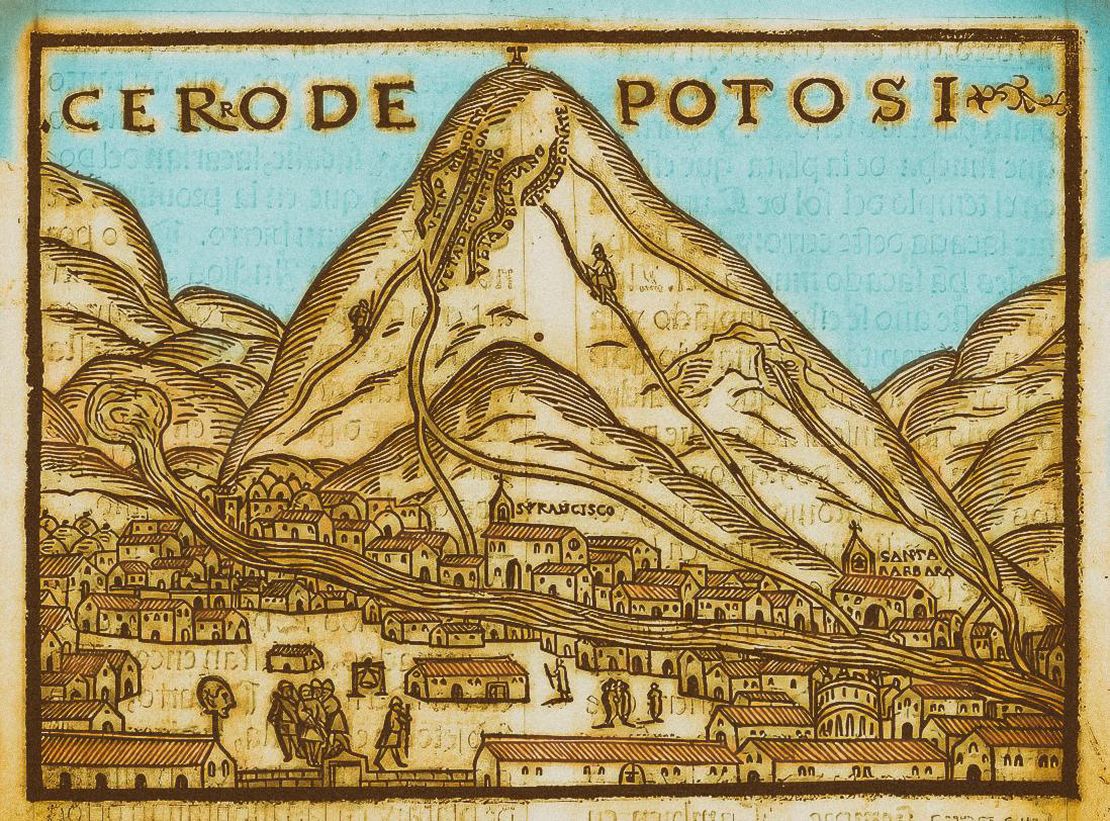

Reducciones (Reductions) is the term used, in the 16th century, to refer to the “Pueblos Reales de Indios” (Spanish crown´s Indian Villages) created by the Spanish colonial state through the forced resettlement of the Indigenous population and their concentration or “reduction” in certain targeted towns. In the Viceroyalty of Peru, particularly in the territory of the former Inca state of Tawantinsuyu, this massive resettlement program began in the 1570s as part of the reforms implemented by Viceroy Toledo with the aim of institutionalizing the presence of the colonial state, consolidating its capacity to directly capture the resources of Andean societies and thus increase the production of the silver mines of Potosí. In the Qullasuyu region, the “reducciones de indios” would allow not only to control and evangelize more systematically, but also to collect the indigenous tribute, and recruit labor more efficiently for the Potosí mines operating under the mita system. Although the results were not as expected, the “Indian reduction” caused a dramatic rearrangement of the territory and the fragmentation and political disruption of the great Aymara lordships in the high plateau.

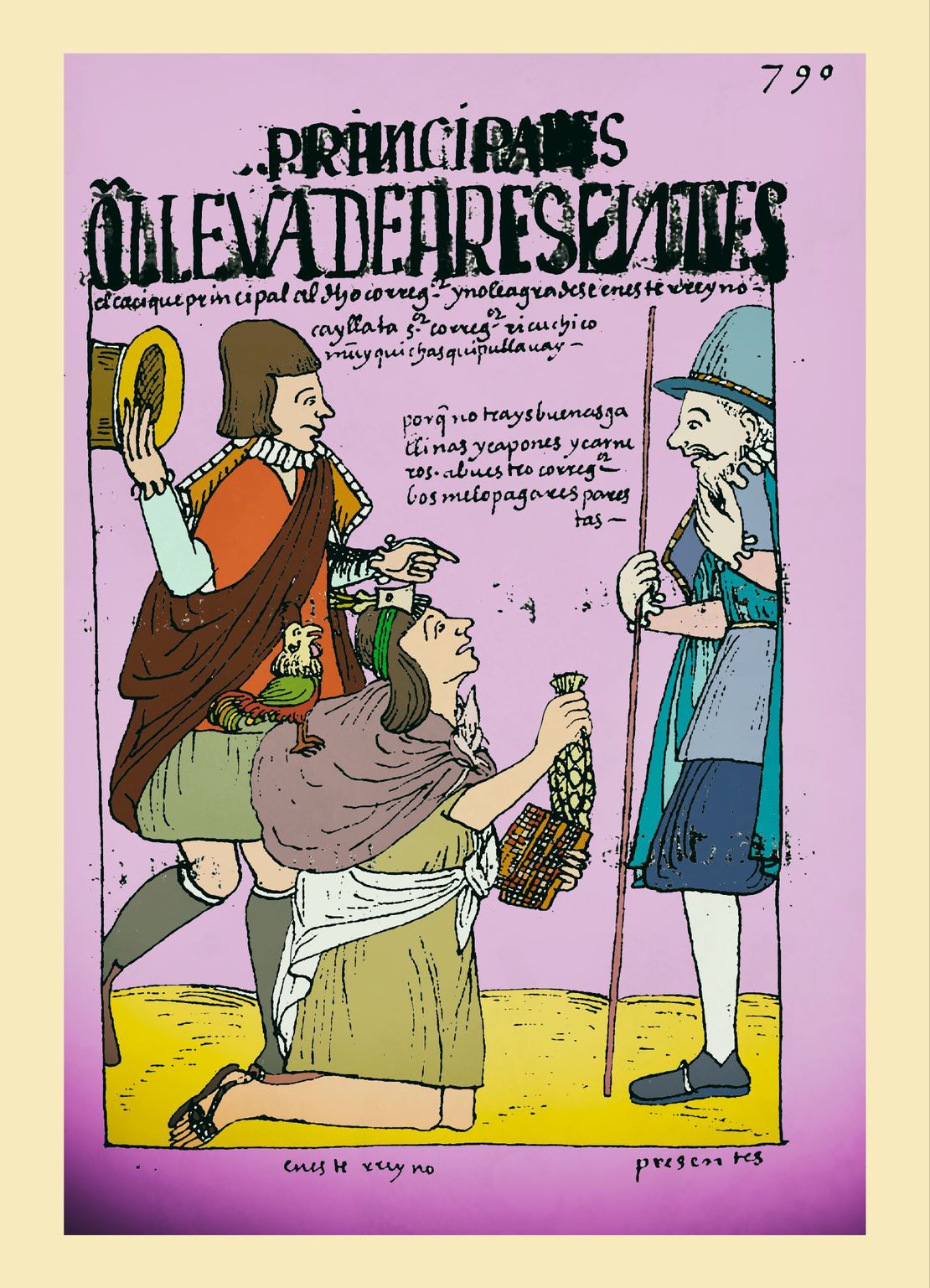

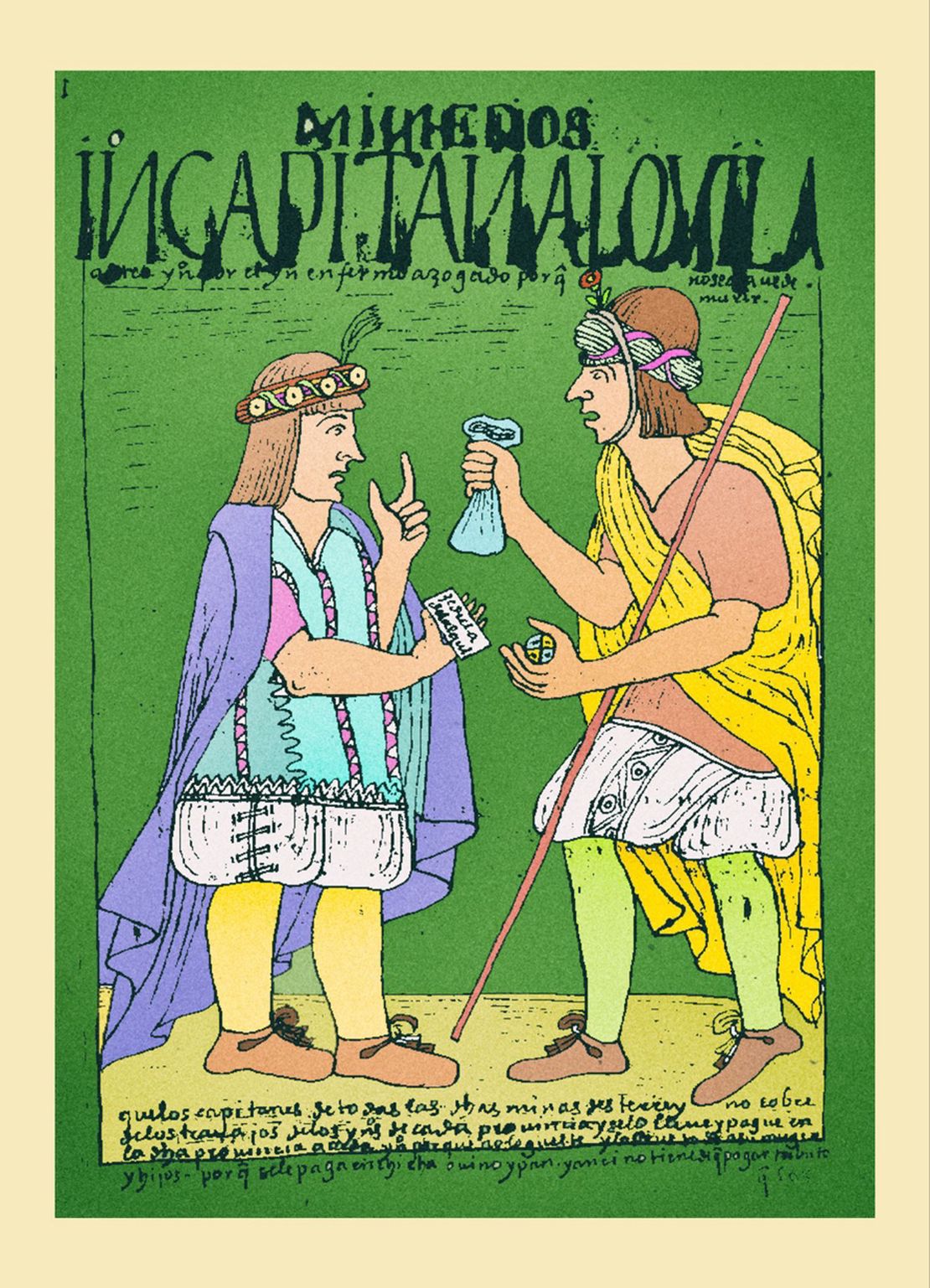

The Toledo reforms constituted the largest set of transformations that the Spanish crown was able to implement in this region. Their design was based on the information gathered through an exhaustive census called Visita General, which consisted of a population count and a thorough investigation of the characteristics of the Indigenous territories, the quality of their natural resources, their surplus production capacity, the features of the Inca state tax system, etc.1 On this basis, the political-administrative organization of the territory was institutionalized, the tax system and labor benefits were rationalized and the location of the royal Indian towns where the Indigenous population would be concentrated was identified. The new tax regime identified two main ways of collecting the tribute the Indians now relocated in the reducciones were subject to: the cash tax to be paid by each “originario” or “native” —physically fit men between 18 and 50 years old registered in a reduction— and the mandatory labor service to be performed in the mines of Potosí from time to time. Thus, this system of forced recruitment of rotating labor known as mita became a policy of the colonial state to subsidize the mining industry in Potosí.2

The monetization of the Indigenous tribute, the institutionalization of the Potosí mita, and the Indigenous reducciones were the three measures that most profoundly affected the territorial and political organization of the Aymara lordships of the Qullasuyu territory. Conceived as a rationalization of the colonial administration of territories and populations and as a systematization of the mechanisms of surplus and labor extraction, these three measures were closely articulated, being the reductions the key piece of the articulation.

Indeed, in the reducciones it was possible to govern the “Indians” and evangelize them in a more orderly manner, collect tribute more systematically and recruit the workers on duty for mita more efficiently. The intrusion of the colonial state into the daily life of the Indians and the surveillance and discipline-imposing mechanisms were expressed in many ways, starting with the layout of streets and regulations on the use of time and space. Following a checkerboard design, each town had a central plaza around which were located the church, the town hall, the jail or incarceration facilities, the market, and a house for Spanish visitors. The Indians who had been relocated had to build their houses along the rectilinear streets that merged at the plaza.3 New institutions were established with Spanish and Indigenous authorities to administer the town and enforce state exactions. The Indigenous authorities became officials paid by the state to collect taxes and recruit mitayos (mita workers).

Despite significant regional variations, the “reducciones de indios” constituted an “attack on Andean kinship networks of unprecedented magnitude.”4 By defining a person’s belonging and identity on the basis of the principle of primary residence in a fixed place, this “attack” undermined the principle of descent that had so far defined the structure of ethnic belonging and the organization of discontinuous territories (vertical archipelagos) of the Aymara lordships.5

Indeed, this ambitious project of forced resettlement implied the disruption of the discontinuous territories of the large Aymara socio-political units, the uprooting of thousands of villages scattered along these vertical archipelagos and the disarticulation of the structure of ethnic belonging —based on the principle of descent— that had ensured their political and economic integration. Families belonging to different Aymara lordships or to different segments of the same lordship were brought together arbitrarily in the same town. Although the “reduced”6 population was organized in groups maintaining elements of the ayllu structure, they were new groups of Indigenous people with different ethnic affiliation.

Therefore, the reduction process implied a profound reconfiguration of ethnic belonging: the new groups, or re-formed ayllus, became the main reference point for the development of new identities and the memory of belonging as Aymara macro political entities began to fade.7 Over time, these reconstituted ayllus would be commonly referred to as “Indian communities.”8

In Toledo’s vision, the reductions should form a republic of Indians separate from the republic of Spaniards and become self-sufficient communities capable of producing a significant surplus to support the tax increase and the number of mitayos. Toledo understood that the sustainability of this project (and of the colonial economy in the region) depended on preserving the agrarian base through the “Indian communities” and the necessary conditions for “their social reproduction following the matrix of the ayllu economy.”9 Thus, the territory of an “Indian reduction” would include an extension of land around the town to be distributed among the ayllus that made up that reduction. Combining elements of Spanish agrarian communities and Andean norms, the Toledo state guaranteed corporate land rights and legitimized usufruct rights for the families of the Indians registered as “originarios” (natives).

Overall, although the result differed greatly from the original design, Toledo’s reforms laid the groundwork for a more institutionalized presence of the colonial state and involved new ways of turning Andeans into “Indians” and “Indians” into subjects of the Spanish empire. Perhaps the greatest success of these reforms was to achieve a significant increase in mining production. Indeed, by the 1590s, Potosí´s silver had reached an unparalleled boom. This boom was due to a combination of important technological innovations, investments in infrastructure and the institutionalization of the mita system. Despite this achievement, Toledo failed in the creation of segregated, sustainable “Indian communities.” The fragile balance between expropriating Indigenous surpluses and guaranteeing the conditions for their production quickly shattered in the face of market forces unleashed by the reforms themselves.

In fact, Toledo’s reforms produced contradictory and unforeseen effects and were resisted in multiple ways. Faced with forced uprooting and resettlement, Andeans responded by waging long legal battles to regain access to ethnic islands or to report abuses perpetrated by colonial authorities. Faced with the pressure of tribute and mita systems, the Andeans responded by fleeing the reductions and/or integrating themselves into the market of the economic space articulated around Potosí where they could sell products, services, or labor.

Fleeing the Spanish crown´s Indian towns where they were registered as “originarios” was undoubtedly the most radical way to avoid tribute and labor obligations. By the end of the 16th century, an increasing number of taxpaying Indians fled in search of other arrangements as “outsiders” in cities, mining camps, haciendas, or other Indian towns. This resistance tactic, however, increased the pressure on ethnic authorities and kinship groups who had to find the money to still pay the tribute and replace them in the mita services shifts or, alternatively, persecute them. This new phenomenon, Indians fleeing to places they were not “native” of, would not have expanded as it did if hacienda owners, mine owners, urban merchants or even authorities from other reductions had not been so willing to hide their new workers.

This unforeseen effect in Toledo’s plan was related to the principle of residence applied to the definition of colonial taxpaying categories: taxpaying Indians were “native” residents of the “Pueblo Real de Indios” where they had rights (access to land) and obligations (tribute and mita systems). Leaving that town and becoming non-residents elsewhere implied escaping the category of taxpaying Indian, but also relinquishing access to land. Thus, the phenomenon of outsiders led to the emergence of an increasing number of landless peasants and implied a recategorization of “Indians” into “originarios” (“native” taxpaying residents with access to land); “outsiders” (non-taxpayers without access to land); and “yanaconas” (dependents of a Spanish lord).10 It was only in the 1740s that the colonial state succeeded in reforming the Indigenous tribute legislation to include “outsiders” (forasteros) as taxpayers. By then, little remained of the reductions originally planned in Toledo´s time.

In summary, although results were not what Toledo had expected, his reforms laid the foundations for a more institutionalized presence of the colonial state, the expansion of an internal market and the consolidation of an economic space that articulated the Indigenous peasant economies with a market economy. This created a hybrid system where the Indigenous peasant economies were forced —through political mechanisms— to subsidize the multiplication of the labor force for the Spanish companies. There is no doubt that Toledo succeeded in significantly increasing silver production volumes in Potosí, but he failed in his project to create sustainable “Pueblos Reales de Indios.” The order Toledo had envisioned of a colonial society based on the division between Spanish and Indian peoples resulted in a “complex fusion of classes, castes and groups in both the Indigenous rural world and the Spanish-dominated urban centers.”11 However, the role of Indigenous communities was firmly established, becoming source for grabbing and collecting surplus and Indigenous labor subsidizing colonial enterprises.

Bibliography:

Abercrombie, Thomas. Pathways of Memory and Power. Ethnography and History Among Andean People. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1988

Cook, Noble David. Tasa de la Visita General de Francisco Toledo. Lima: Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, 1975.

Klein, Herbert. Bolivia: The Evolution of a Multi-ethnic Society. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Larson, Brooke. Colonialismo y Transformación agraria en Bolivia: Cochabamba 1550-1990. La Paz: Vicepresidencia del Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia, 2017.

Murra, John. Formaciones Económicas y Políticas del Mundo Andino. Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, 1975.

Saignes, Thierry. “De la Filiation à la Résidence: les Ethnies dans les Vallées de Larecaja.” Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales, 33, no. 5/6 (1978): 1160-1181.

Sánchez-Albornoz, Nicolás. Indios y Tributos en el Alto Perú. Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, 1978.

Zagalsky, Paula. “El Concepto de ‘Comunidad’ en su Dimensión Espacial. Una Historización de su Semántica en el Contexto Colonial Andino (Siglos XVI-XVII).” *Revista Andina no. *48, (2009): 57-90.

Noble David Cook, Tasa de la Visita General de Francisco Toledo (Lima: Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, 1975). ↩︎

Brooke Larson, Colonialism and Agrarian Transformation in Bolivia: Cochabamba 1550-1990 (La Paz: Vicepresidencia del Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia, 2017). ↩︎

Thomas Abercrombie, Pathways of Memory, and Power. Ethnography and History Among an Andean People (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1988). ↩︎

Larson, Colonialismo y transformación agraria en Bolivia: Cochabamba 1550-1990, 125. ↩︎

Thierry Saignes, “De la Filiation à la Résidence: les Ethnies dans les Vallées de Larecaja,” Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales, 33, no. 5/6 (1978): 1160-1181. ↩︎

Translator´s Note: the term “reduced” points to Indigenous populations living in reductions, yet also suggesting being reduced in size and constrained in the territory. ↩︎

Abercrombie, Pathways of Memory, and Power. ↩︎

Paula Zagalsky, “El Concepto de ‘Comunidad’ en su Dimensión Espacial. Una Historización de su Semántica en el Contexto Colonial Andino (siglos XVI-XVII)” *Revista Andina no. *48, (2009): 57-90. ↩︎

Larson, Colonialismo y transformación agraria en Bolivia: Cochabamba 1550-1990, 122. ↩︎

Nicolás Sánchez-Albornoz, Indios y Tributos en el Alto Perú (Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, 1978). ↩︎

Herbert Klein, *Bolivia: The Evolution of a Multi-ethnic Society (*New York: Oxford University Press, 1992), 51. ↩︎

![[*Government of Peru, with all things pertaining to it and its history*; \[La Plata, 1567?\]](https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/collections/obadiah-rich-collection#/?tab=navigation&roots=dfef40d0-25e3-0130-419d-58d385a7b928), folio 38r. New York Public Library Digital Collections. Digitally intervened by Mauricio Sánchez Patzy. Source: Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library. [Juan de Matienzo.](https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/collections/obadiah-rich-collection#/?tab=navigation&roots=dfef40d0-25e3-0130-419d-58d385a7b928) Accessed: June 24, 2024. [https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/487d21a0-2601-0130-a73a-58d385a7b928](https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/487d21a0-2601-0130-a73a-58d385a7b928)](/images/content/TL003Reducciones/image1_hud9d1851ff32d2707570b3786a426d977_206844_1110x0_resize_q80_lanczos.jpg)