Abstract

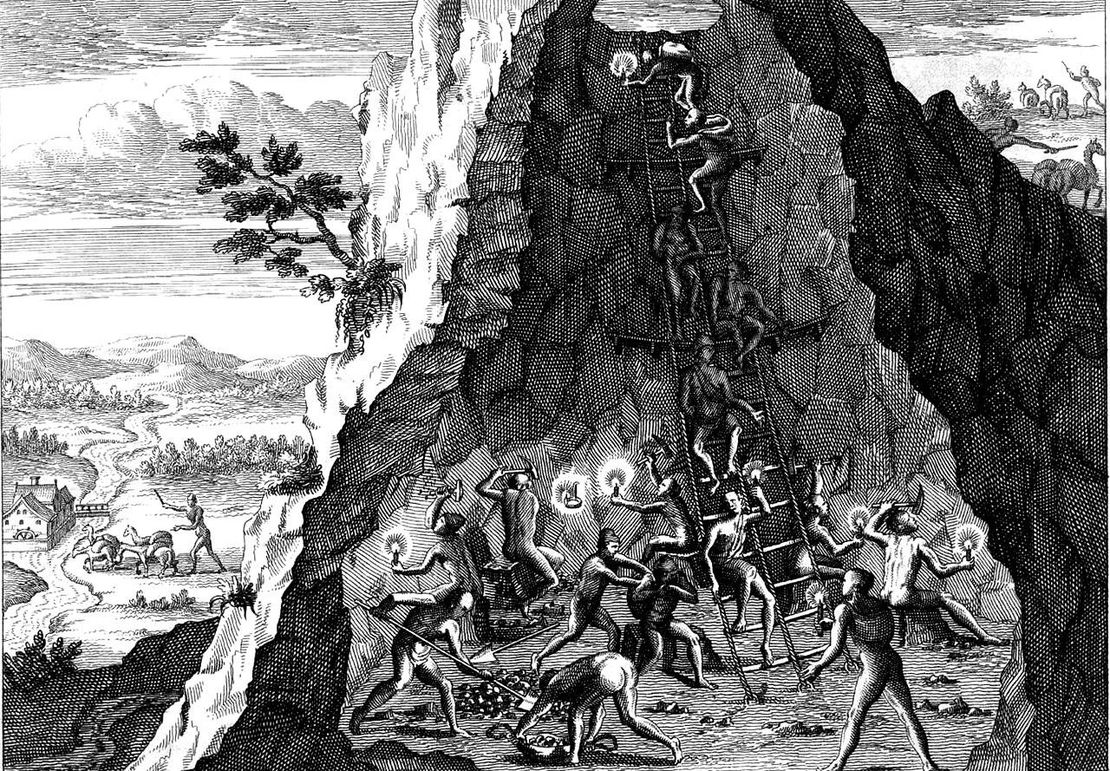

The Encomienda and the Repartimiento were the first institutions of Spanish colonization established by the conquistadors in the Americas. The Repartimiento was a way of organizing the inhabitants of a vaguely defined area into groups or population units subject to labor and tax services. The Encomienda, or repartimiento of Indians in encomienda, consisted of “encomendar” (to deliver or entrust) the Indians of a repartimiento unit to a Spanish subject (conquistador, colonizer) who thus became encomendero. As a reward for his services or military valor, he would be granted the right to receive the tribute that the Indians in his charge had to pay to the Spanish Crown. In turn, the encomendero had to guarantee the adequate indoctrination of the Indians in the Catholic faith. From its improvised implementation in the Caribbean in the early years of the conquest until its final abolition in 1718, the encomienda system underwent multiple modifications that redefined its duration, the rights and obligations of encomenderos and encomendados, as well as the specific contents of the indigenous tribute that encomenderos would receive. In the colonization of state societies, as was the case of the Tawantinsuyu, an Inca State, the encomienda presented singular features.

Throughout the 16th century, the Crown enacted a series of laws limiting the rights of the encomenderos to prevent the development of a parallel seigniorial power, and responding to the growing complaints —filed by some church representatives— of the abuses perpetrated by the encomenderos against the indigenous encomendados. Although the encomienda system took different forms according to each region´s specific characteristics, its importance declined, as a colonial state emerged and consolidated with new institutions and political structures directly controlled by the Spanish Crown.

Encomienda in the Central Andes

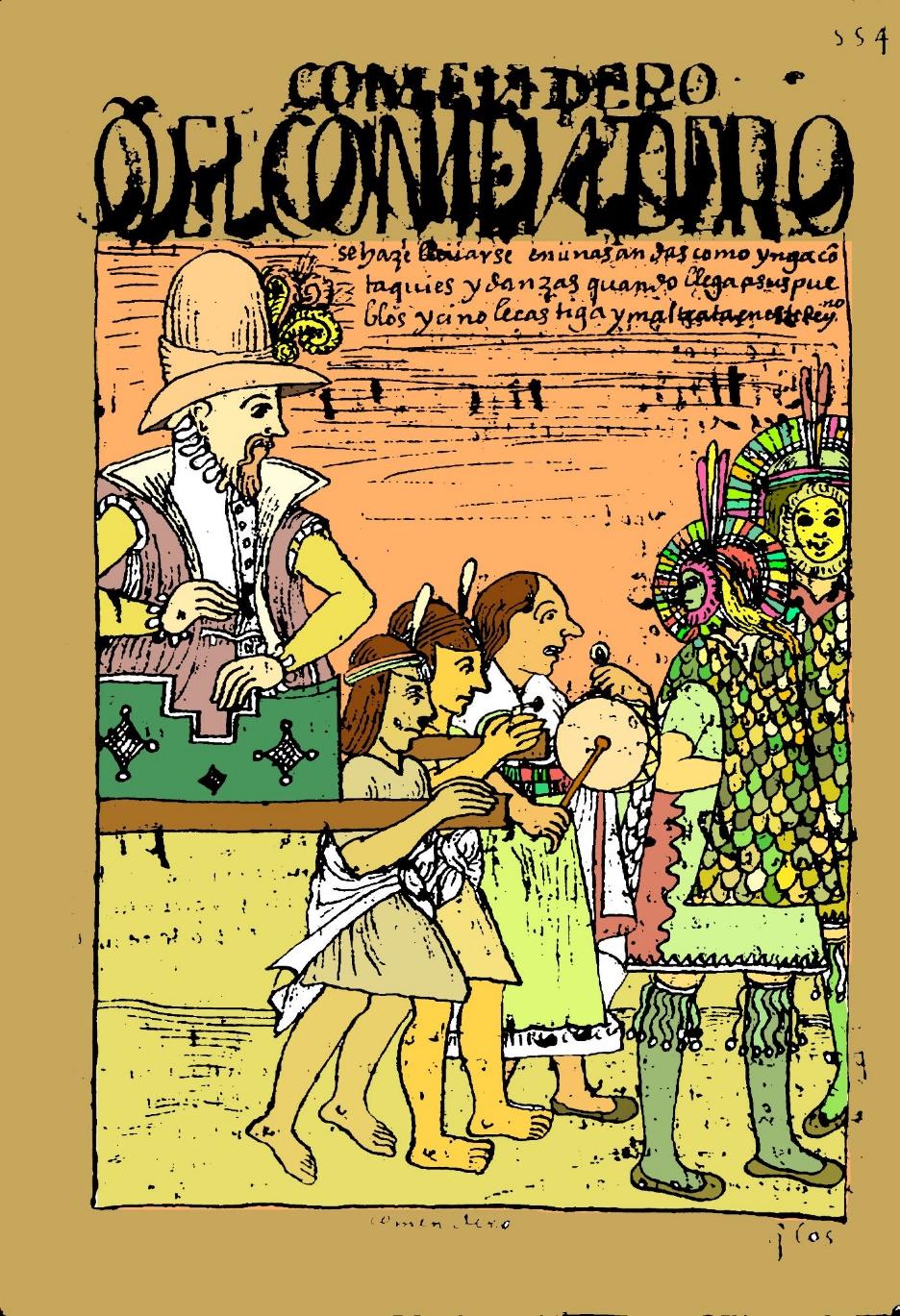

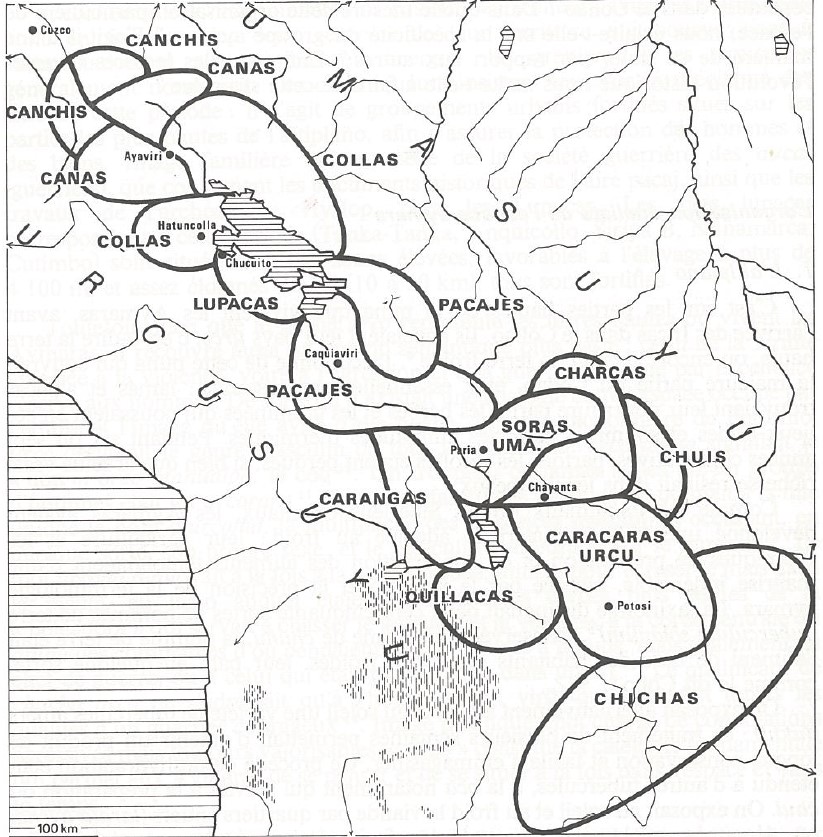

In the conquest of the Inca State, and particularly of the Aymara lordships of Qullasuyu, the encomienda system served to “organize the extraction of the surplus without altering the mechanisms by which production was structured” before the Spaniards´1 arrival. Indeed, as state societies, Andean societies not only had the capacity to produce enormous agricultural surpluses and the technology for the extraction and processing of minerals, but also possessed institutions that regulated the transfer and redistribution of surpluses. During the first 2 to 3 decades of colonization (1530´s – 1560´s), all the goods necessary for subsistence consumed by Spaniards and natives, as well as the silver that was traded and exported, were not only produced using indigenous labor and their own technologies, but also within the framework of their own relations and production system and organization.

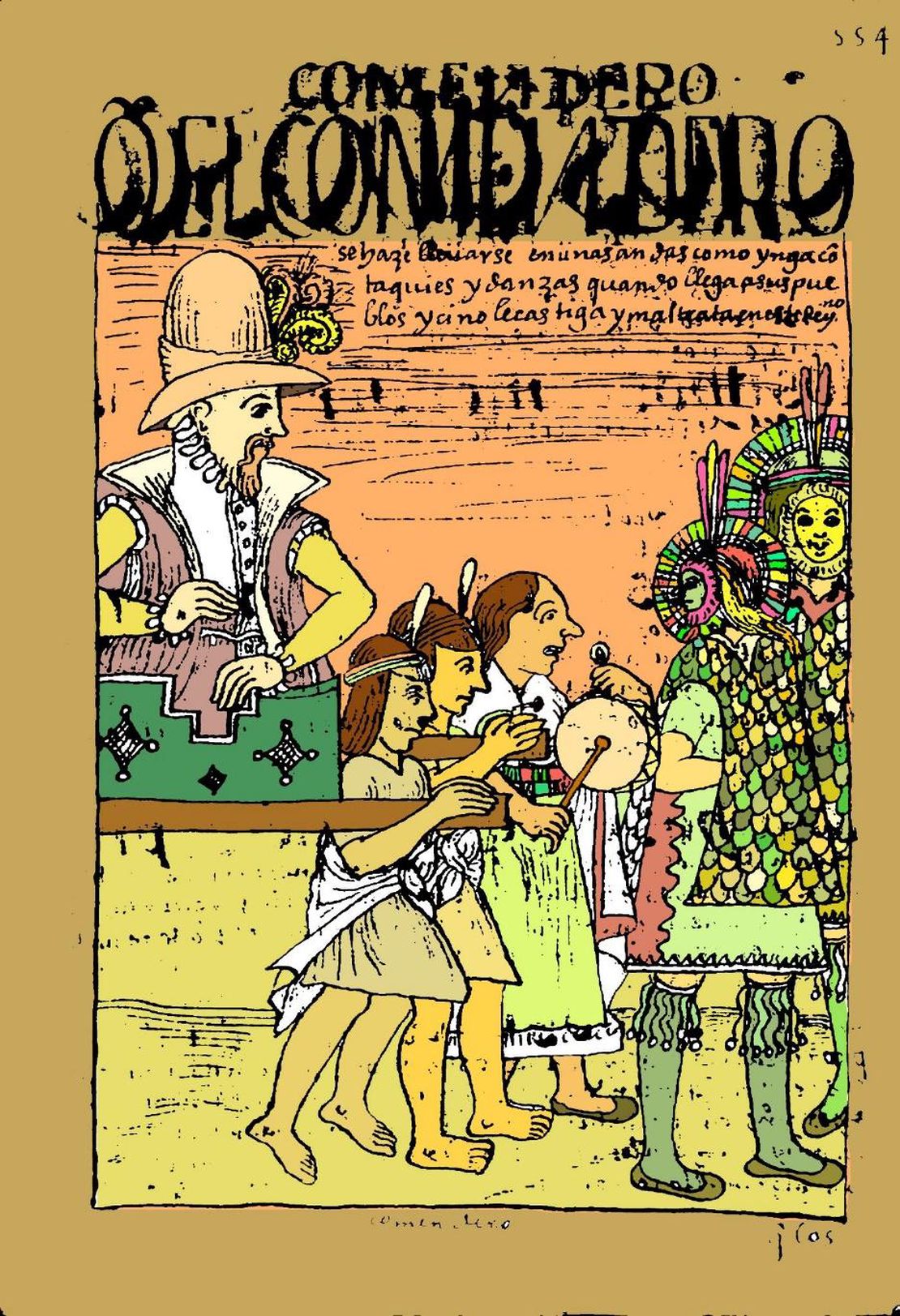

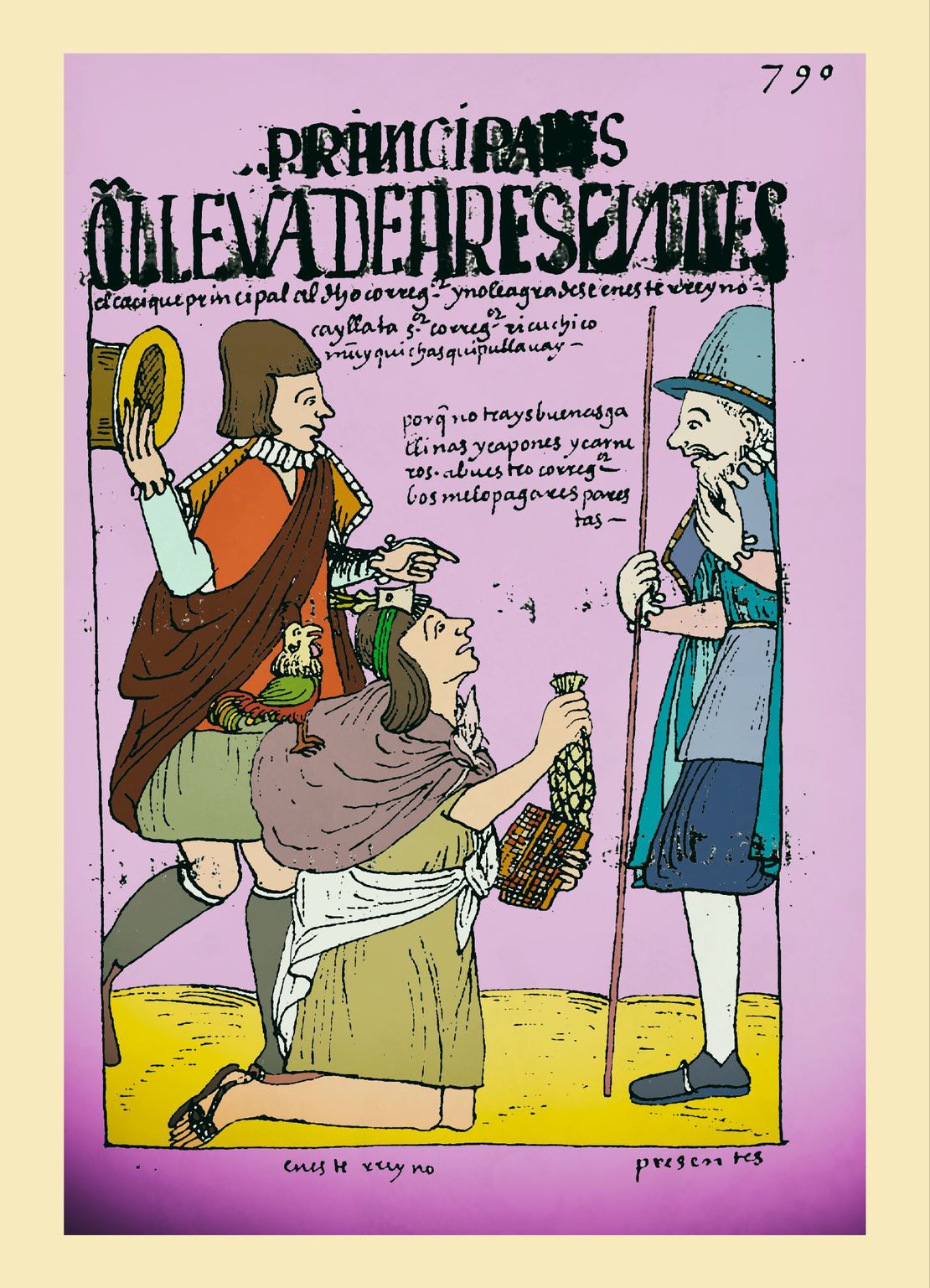

In this context, many indigenous authorities managed to have a certain bargaining power and significant room for maneuver. Indeed, the greater or lesser difficulty in obtaining the tribute —having the indigenous labor force and appropriating the goods and services produced under the local Andean system— depended on the relationships that the encomenderos were able to establish with the indigenous authorities either through alliances and incentives or through openly violent forms of pressure to obtain their cooperation. Thus, the encomienda gradually deepened and restructured —in some regions more than others—, the socio-economic hierarchies that already existed in the Inca State, but in a more regulated and controlled manner. In this context, colonial dispossession consisted, above all, of violent processes of expropriation of the labor force and the surpluses produced by Andean societies.

In general, the encomenderos would sell on the market part of the goods received through tribute (agricultural products, clothing, utensils, etc.), perceiving a monetary income that allowed them to accumulate capital to invest in different ventures, especially mining. In other words, by converting use values into merchandise, the commercialization of tribute allowed the capitalization of the encomenderos and the development of an internal market around the silver economy of Porco and Potosí mines. Over time, the gradual integration of the indigenous population into this market led to the monetization of the tribute.

The rise of the encomienda in Qullasuyu coincided with the first silver boom/cycle (1545-1560). During this period, the first viceroys of Perú —the viceroyalty was created in 1542— tried to apply legislation aiming to the elimination of the encomienda, but had to retreat in the face of the violent reaction of the encomenderos. However, the importance and efficiency of this institution —as a mechanism of surplus extraction— began to decline in the 1560s in the context of the mining crisis (and of production in general). This crisis was due not only to the depletion of the surface mineral deposits, but also to the fact that the Andean silver production system had been exploited to the limit of its capacity. This was in turn coupled with the demographic disaster caused by the diseases arriving with the Spaniards, and with the excessive exploitation of the indigenous labor force.

This situation required the Crown to implement a set of structural reforms (economic, technological, institutional, and territorial) to rebuild the institutionality of the colonial state and develop new forms of production and surplus extraction more directly linked to the Crown. Thus, the consolidation of the colonial state —initiated with the reforms of Viceroy Toledo in the 1570s— progressively undermined the power of the encomenderos and the validity of the encomienda.

Bibliography

Assadourian, Carlos Sempat. The Colonial Economic System. Mercado Interno, Regiones y Espacio Económico. Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, 1982

————— “La Renta de la Encomienda en la Década de 1550: Piedad Cristiana y Desconstrucción.” Revista de Indias 48(1988): 109-145.

Larson, Brooke. Colonialism and Agrarian Transformation in Bolivia: Cochabamba, 1550 - 1900. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. 1988.

Presta, Ana María. Encomienda, Family and Business in Colonial Charcas. Los Encomenderos de La Plata 1550 - 1600. Sucre: National Archives and Library of Bolivia. 2014

Spalding Karen. Huarochirí. An Andean Society under Inca and Spanish Rule. Stanford: Stanford University Press. 1984.

Stern, Steve. Peru’s Indian Peoples and the Challenge of Spanish Conquest. Huamanga to 1640. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. Second edition, 1993.

Karen Spalding, Huarochiri. An Andean Society under Inca and Spanish Rule (Stanford University Press, 1984), 124 (own translation). ↩︎

Citation

Medeiros, Carmen, and Radek Sánchez Patzy. 2024. 'COLONIAL LEGISLATION AS THE FRAMEWORK FOR DISPOSSESSIONS IN THE CENTRAL ANDES: THE ENCOMIENDA SYSTEM'. Dispossessions in the Americas. https://staging.dia.upenn.edu/en/content/TL001Encomienda/