Abstract

Reproductive violences like forced sterilization are central to colonial projects of dispossession. Between 1996 and 2000, approximately 275,000 Indigenous women were sterilized in Peru. While organizing for justice in the courts, many affected women have continued to be beset by illnesses that preclude them from carrying out the everyday labor that reproduces their more-than-human community, or ayllu. While some of these illnesses remain mysteries to medical doctors, the Mosoq Pakari Sumaq Kawsay (MPSK) healing center has begun treating them for susto or soul loss through various modalities including shamanism, curanderismo, herbal medicine, psychology, and the law. The following is a short documentary chronicling the healing workshop that took place at MPSK the summer of 2023. At the basis of these justice-seeking and healing techniques is the principal of ayni, or the ethics of reciprocal care in ayllu. These healing modalities reconnect sterilized women with themselves and their communities, helping them to remember and re-member the shared body of ayllu which was rent by the forced sterilizations. This healing work is one expression of the cosmopolitics of health, or Indigenous peoples’ defense and cultivation of the more-than-human worlds necessary for future well-being.

High in the Andes of southern Peru, Runa (Quechua) leader Hilaria Supa Huaman and I sit on the grounds of the Mosoq Pakari Sumaq Kawsay (New Dawn for Good Living) healing center. The sun warms our backs as we talk about the forced sterilizations that took place in our country in the 1990s. 314,000 people were sterilized under the National Program of Reproductive Health and Family Planning from 1996 to 2000. Around 289,000 of the people sterilized were women and over 92% were Indigenous. Studies have found that only 35% of all people were given full and informed consent, including information regarding tubal ligation as a permanent form of contraception.1 Many women were also lied to, told that they were getting a check-up, or were harassed by medical workers until they consented to go to the medical posts.2 The surgeries themselves were often hurried or unsanitary. Many people were injured and at least fifteen died.3

As we sat in the morning sun pealing lima beans, I asked: “Hilaria, why did the Fujimori government do this, sterilize Indigenous people, without their consent?” She turned to me, her braids and tall hat framing her face. Hilaria, who has worked with affected women since the late 1990s, contemplated:

When I think about why Fujimori carried out this program, I think it was a plan to reduce the Indigenous population so that new leaders would not be born. Those children who weren’t born would have been leaders in their communities today. We [Runa people] lack leaders…[Fujimori] had sold off several Peruvian interests, including mining interests, and, at the same time, he was trying to exterminate the peoples [un pueblo] that could stop what he was doing. In that moment, all of us [Indigenous peoples] were terrorists, those of us who defended our lands and rights, those of us who spoke up…4

For Hilaria and other Indigenous activists across the Americas, reproductive violences (like enforced sterilization, rape, and the disappearance and murder of Indigenous women), are part of larger colonial projects to dispossess Indigenous peoples of their lands. Forced sterilization has been used by many governments to dispossess Indigenous in the Americas. Scholars estimate that 25 percent of all American Indian women were sterilized between 1970 and 1977,5 and enforced sterilization of Indigenous peoples has or is taking place in Canada,6 Mexico,7 Bolivia,8 Brazil, Belize, and beyond. Most instances of enforced sterilization have taken place within larger projects of economic development that require the dispossession of Indigenous territory.

In the case of Peru, Indigenous peoples were sterilized during a time of economic growth premised on an expansion of extractive industry. Some of the highest rates of sterilization occurred in areas with new or renewed land concessions to foreign mining and oil companies. 9

Enforced sterilization is a human rights violation, more specifically, a crime of genocide.10 However, it is difficult for survivors to get justice from the states that commit this crime. Some survivors have had success: a group of sterilized First Nations women in Canada are currently pursuing a class action suit which has had success in Canadian courts. The Canadian Parliament is also seeking to make forced sterilization a crime with required jail sentences.

Affected women in Peru have been organizing and fighting for legal justice since the late 1990s. They brought a legal case against the state of Peru in 2003, but it was only allowed to go to court December of 2021—18 years after it was first presented—and has recently been closed again. Affected women in Peru are not waiting for the government to confer justice, however.

Figure 3: affected women signing into the meeting of the Association of Women Affected by Forced Sterilization-Anta in 2020. Photo by author

Many affected women continue to be beset by a combination of illnesses that keep them from carrying out crucial labor that helps reproduce human and other-than-human family and community, including working in the fields, cooking, raising children, making chicha (corn beer), and engaging in everyday ritual and in the social life of ayllu.11 Ayllu is the Runa word for community, but this community is more-than-human. It is made up of humans, plants, animals, ancestors, and earth-beings like mountains, lakes, rivers that work together to sustain each other’s lives. Because ayllus are tight-knit and the labor of all is required to keep the community healthy, sterilized women’s sickness is felt not only at the level of their bodies or families, but throughout entire communities.

When affected women seek medical attention, doctors often dismiss or are baffled by their symptoms. But where doctors and psychologists struggle to understand women’s ailments, in Runa “worlds of health”12 women’s constellations of symptoms are deeply meaningful.

One day as we were cruising down the highway toward Cusco, I asked: “Hilaria, the symptoms that women have: nervousness, lack of appetite, not being able to sleep…do you think they have PTSD?” “Of course they do!” She answered incredulous from under her tall hat. “But what you call psychology we call spirituality. Affected women would like access to psychologists. They have the right to see one through the SIS [Public Insurance], but no psychologist comes out here, and it was hard for women to get to a town. In any case, the doctors and psychologists don’t understand the spiritual part. They only want to treat una partecita, just a part of you, no más. These women have susto. Can you imagine waking up on the floor with women screaming and children crying all around you, not knowing what happened to you? That is a big susto.”13

In Runa medicine, susto is an enfermedad de la tierra, an “illness of the land,” a class of affliction that stems from breakdowns of social relations among humans and their other-than-human kin. These are distinct from “illnesses from God,” that come from bacteria, viruses, or fungi, and must be treated by a medical doctor.14 Most anthropological work on susto’s origins have bracketed off the main symptom: spirit loss. This makes it hard to understand what this illness is for Runa, what causes it, and how it can be healed.

In Runa medicine, el espíritu or spirit, is a part of the body just like the heart, brain, or lungs, that makes social relations possible. If a person gets susto and it goes untreated, it can go deeper and deeper until it reaches a person’s ukusunqu, or inner heart, the “space of resistance, critique [as thinking-feeling], and mindful watching.”15 If susto reaches the inner heart, the patient can lose their will to self-protect and to protect relationships. The death of relation with oneself and with others is the death of a person recognizable as a human for Runa people: without a sociality that is collectively oriented, that thinks in terms of relations, that person is no longer Runa, no longer a “real human.”

Taking forcibly sterilized women at their word, that they are suffering from susto, that their souls have fled, is an important step toward providing therapies that help them and their communities and is precisely what Hilaria and her compañeras are working to do at Mosoq Pakari Sumaq Kawsay (MPSK). From the center’s placement in a “spiritual geography,”16 to its architecture, which mirrors the three dimensions of the Runa cosmovision, to the therapies that have been and will be employed there, MPSK is working to heal sterilized women and the larger socionatural world of the ayllu. This healing can be thought of as a process of reconnection, of remembering and re-membering the shared body of ayllu that sterilization and centuries of colonialism have torn, but not broken.

Figure 4: The Mosoq Pakari Sumaq Kawsay healing center. Photo by author

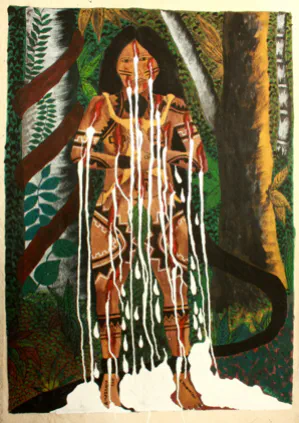

The following is a short documentary chronicling a healing workshop undertaken at MPSK the summer of 2023. The workshop took place on the land, outside, and in spaces that were familiar and meaningful to the women who attended. The workshop also took place in Runasimi (Quechua), not in Spanish, allowing women (many of whom are monolingual Quechua speakers) to fully participate. The workshop blended psychology and Runa medicine—one did not replace the other. Bringing psychological or biomedical tools into traditional healing spaces means, as de la Cadena puts it, knowing more, not better. Sharing the healing space with children and other members of family also means that healing becomes a space of knowledge sharing and part of an engine of Runa future making.

At the basis of the center’s healing techniques is the principal of ayni, or reciprocal care, a principle of life that has sustained Runa through five hundred years of struggle against settler colonial structures and for Runa life. By reconnecting, transferring traditional knowledge around cosmovision, plant medicines, while incorporating supporting aspects of biomedicine and psychology, and doing so on the land in the company of earth beings, the healing center is doing nothing less than powering a “radical resurgence”17: helping power Runa futures based in Runa ethics and traditional knowledge.

Credits: Lucía Stavig, director; Raymundo Ibarrola, videographer; Alex Rocha, editor.

Silvio Rendón, “Sterilization Policy with Incomplete Information: Peru 1995-2000,” IZA Institute of Labor Economics, Discussion Paper Series, no. 13859 (2020): 1–25, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3730457. ↩︎

Alejandra Ballón Gutiérrez, ed., Memorias Del Caso Peruano de Esterilización Forzada, Colección Las Palabras Del Mudo (Lima, Perú : Biblioteca Nacional del Perú, Fondo Editorial, 2014). ↩︎

Alberto Chirif, ed., Perú: Las Esterilizaciones Forzadas, En La Década Del Terror: Acompañando La Batalla de Las Mujeres Por La Verdad, La Justicia, y Las Reparaciones (Lima, Peru: IWGIA and DEMUS, 2021). ↩︎

Hilaria Supa Huamán, “¡Hasta Dónde Puede Llegar Un Ser Humano Con El Menosprecio y El Racismo!,” in Las Esterilizaciones Forzadas En La Década Del Terror: La Batalla de Las Mujeres Por La Verdad, La Justicia y Las Reparaciones (IWGIA, International Working Group on Indigenous Affairs, 2021), ??? ↩︎

Jane Lawrence, “The Indian Health Service and the Sterilization of Native American Women,” American Indian Quarterly 24, no. 3 (2000): 400–419. ↩︎

Karen Stote, An Act of Genocide: Colonialism and the Sterilization of Aboriginal Women (Halifax: Fernwood Publishing, 2015). ↩︎

Pierre Gaussens, “Esterilización forzada de hombres indígenas: una faceta inexplorada,” Revista Interdisciplinaria de Estudios de Género de El Colegio de México 6 (November 17, 2020): 1–37, https://doi.org/10.24201/reg.v6i1.639. ↩︎

Yawar Mallku, 1969. ↩︎

Rocío Silva Santisteban, Mujeres y conflictos ecoterritoriales: impactos, estrategias, resistencias, Primera edición (Lima, Perú : Madrid, España : Barcelona, España: Centro de la Mujer Peruana Flora Tristan : DEMUS Estudio para la Defensa de los Derechos de la Mujer : Coordinadora Nacional de Derechos Humanos ; AIETI Asociación de Investigación y Especialización sobre Temas Ibeoramericanos ; Entrepueblos, 2017); Rocío Silva Santisteban, “Esterilizaciones Forzadas: Biopolítica, Patriarcado y Genocidio,” in Peru; Las Esterilizaciones Forzadas, En La Década Del Terror: Acompañando La Batalla de Las Mujeres Por La Verdad, La Justicia y Las Reparaciones, ed. Alberto Chirif (Lima: IWGIA and DEMUS, 2021), 57–94; Alejandra Ballón Gutiérrez, “El Caso Peruano de Esterilizaciones Forzadas: Una Pieza Clave Del Conflicto Armado Interno,” in Peru; Las Esterilizaciones Forzadas, En La Década Del Terror: Acompañando La Batalla de Las Mujeres Por La Verdad, La Justicia y Las Reparaciones, ed. Alberto Chirif (Lima: IWGIA and DEMUS, 2021), 139–64. ↩︎

Ñusta P Carranza Ko, “Making the Case for Genocide, the Forced Sterilization of Indigenous Peoples of Peru,” Genocide Studies and Prevention 14, no. 2 (September 2020): 90–103, https://doi.org/10.5038/1911-9933.14.2.1740. ↩︎

Ballón Gutiérrez, Memorias Del Caso Peruano de Esterilización Forzada; Sara Cuentas Ramírez, “La Verdad Está En Nuestros Cuerpos:” Secuelas de Una Opresión Reproductiva (Lima: IAMAMC, 2016); Julieta Chaparro-Buitrago, “Debilitated Lifeworlds: Women’s Narratives of Forced Sterilization as Delinking from Reproductive Rights,” Medical Anthropology Quarterly 36, no. 3 (2022): 295–311, https://doi.org/10.1111/maq.12700; Lucía Stavig, “A New Dawn for Good Living: Women’s Healing and Radical Resurgence in the Andes” (Dissertation, Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2022). ↩︎

Julio Portocarrero and Esther Jean Langdon, “Presentación: Antropología médica y de la salud: Aportes desde el Sur Global,” Anthropologica 38, no. 44 (May 28, 2020): 5–12, https://doi.org/10.18800/anthropologica.202001.001. ↩︎

Stavig, “A New Dawn for Good Living: Women’s Healing and Radical Resurgence in the Andes,” 59. ↩︎

José Yánez del Pozo, Allikai: La Salud y La Enfermedad Desde La Perspectiva Indígena (Quito: Abya Yala, 2005). ↩︎

Luis Mujica Bermúdez, “‘Coronavirus’ Como Manchachi: Notas Acerca de Las Concepciones y Conductas Ante El Miedo,” Revista Kawsaypacha 5, no. ene-jun (2020): 65–106. ↩︎

Ruth Van Dyke, Sacred Geographies, ed. Barbara Mills and Severin Fowles, vol. 1 (Oxford University Press, 2017), https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199978427.013.37. ↩︎

Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom Through Radical Resistance (Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2017). ↩︎