Abstract

This research gathers the phonographic recordings of Bolivian musician Felipe V. Rivera (1896-1946) in a unique catalog. The collection brings together pieces of the Andean musical and sound heritage of the regions of western Bolivia and northern Argentina that are currently scattered throughout various institutional, family, and personal archives. The most important of these archives is the one compiled under the custody of Ilda Rivera (1930-2023) —Felipe V. Rivera´s fifth daughter—, and currently in the possession of her son Horacio Ovando (Jr.), in San Salvador de Jujuy, Argentina. The survey and data collection of these archives include the drafting of detailed files for each song recorded by Felipe V. Rivera. In turn, the cataloguing includes documents written by Rivera, his related correspondence, press material and photographs. At the same time, the Project encompasses the dissemination and circulation of the outcomes obtained through various products and activities, and the conservation of the documents in a safe and stable link hosted by the Van Pelt-Dietrich Library server, at the University of Pennsylvania.

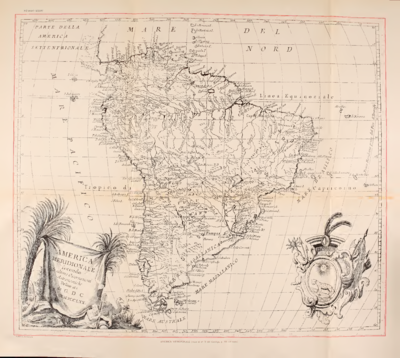

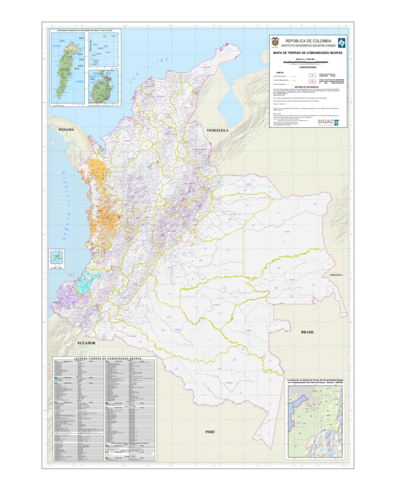

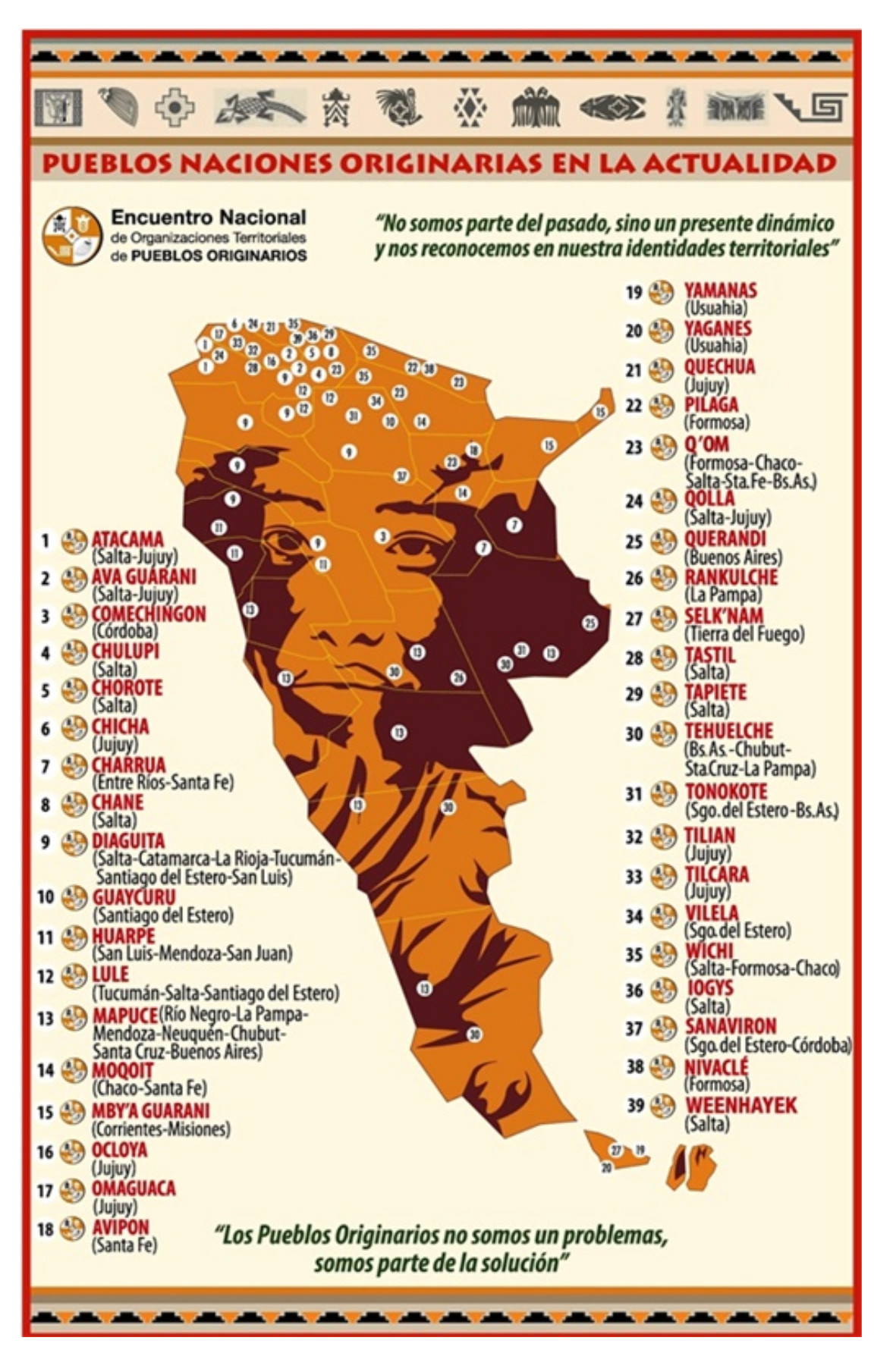

Rivera was born in Suipacha in 1896, remarkably close to the border separating the Potosí region from Argentina. Between 1931 and 1946, he led a prolific music career. During these active years, he devoted his time to compiling Bolivian traditional music, some of it from the Puna region in Jujuy, and composed songs that would outlive him and leave an imprint in Andean popular music. Despite his work, his name fell gradually into oblivion. During that brief period, he recorded around 350 songs for RCA Victor and Odeon in Buenos Aires. This surprising number of compositions and compilations placed him among the top musicians with the largest number of recordings at the time. Rivera´s life and work express the nuances of social relations at the border between Argentina and Bolivia. His story attests to the migration flows from southern Bolivia to Jujuy and Salta and highlights the importance of music in this journey. Although his project was cut short by an early death, his legacy had —and still has— sufficient depth to influence the trajectory of Andean music —both from Bolivia and Argentina— in the ensuing decades.

Felipe V. Rivera at the Bolivia-Argentina Border.

Carlos Vega. Figure: Carnavalito, La Quiaca, 1932. Source: Instituto Nacional de Musicología “Carlos Vega.“

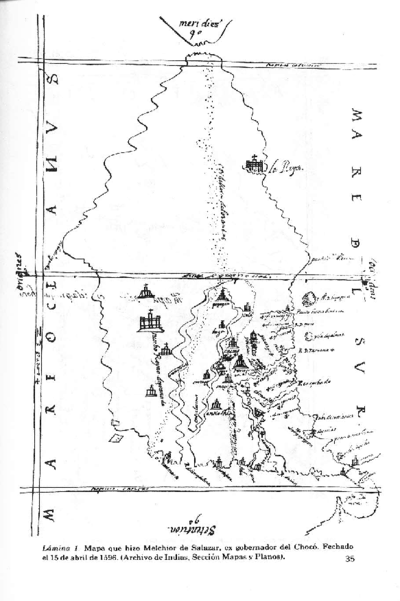

Rivera was born in the Chichas region —south of Potosí— and worked as a store manager in the mining camp sites of Lípez —southwest of Potosí. These regions were linked through commercial ties with what is now northwestern Argentina before the arrival of the Spaniards. These bonds would be further strengthened during the colonial period.

Delving into Rivera´s life and work allows us to have a closer look into the bundle of social relations that intertwined at the border between Argentina and Bolivia, while exploring the history of migration that took place in southern Bolivia. Rivera went to Villazón and from there to La Quiaca, where he crossed the border through a bridge, at a time when borders were beginning to look as we know them today. The railroad transformed the economic and political flows of the region and turned Villazón —where Rivera settled in 1925— and La Quiaca —where he would later settle permanently in 1929— into two towns with thriving economies, leveraged on commercial activities, the railroad service, and the mining industry boom.

Orquesta Típica from La Quiaca region. Neighbors from La Quiaca. Felipe V. Rivera is the second musician standing on the right and holding a quena. (Family Martínez´s Archive, La Quiaca), ca. 1930s.

Self-taught, artistically gifted and displaying a diligent entrepreneurial spirit, Rivera worked as a customs agent and warehouse manager in various mining camp sites in Chichas and Lípez throughout his life. He was a metal chisel engraver, a rubber and metal stamps manufacturer. He was a poet and ventured into the performing arts: dance and theater. Of all the disciplines he took up throughout his life, the most important one was —undoubtedly— music. He knew how to benefit from the geographical conditions and the historical juncture he had to traverse to manage his business enterprise, which would allow him to launch his artistic project and legacy. He aimed at leaving a rich and sonorous record of Bolivian music using the new and enabling technologies.

Between 1931 and 1946, Rivera´s musical career was as prolific as it was frantic. He was only forced to make a brief hiatus between 1932 and 1935, during the Chaco War fought between Bolivia and Paraguay. His endeavor encompassed highly relevant tasks such as compiling different traditional music from Bolivia —some of it from the Puna region in Jujuy—, and composing songs that outlived him and left an imprint in Andean folklore music, even though his name fell gradually into oblivion. In that brief time, he recorded around 350 songs for RCA Victor and Odeon in Buenos Aires, an extensive series of compositions and compilations that place him today among the top musicians of his time with the largest number of recordings.

In 1929, Rivera settled in La Quiaca and founded the Casa Rivera. This general store offered a range of products, including household appliances, musical instruments, gramophones, and records. A few years later, he became a music producer, managing and overseeing all the details of his music career. He was also the director of different Bolivian orquestas típicas or traditional folklore ensembles with which he performed at concerts in theaters and in radio stations from La Paz to Buenos Aires.

The Recordings of Felipe V. Rivera: Genres, Instruments, Technical and Stylistic Innovations.

Rivera ventured into an endless number of Bolivian musical genres: adoraciones, bailecitos, boleros de caballería, cuecas —the genre he recorded most of the time—, huayños with different types of orchestrations —anatas, sikus, vocals, etc.— and kaluyos; pasacalles, plegarias, tonadas, tristes, yaravíes, trotes, valses, zambas and zapateos, also Inca fox trots, taquiraris and carnavales from eastern Bolivia. He also resorted to different instrumental sections that resulted in a wide range of timbres and sound effects (vibrant and reverberating) through the basic ensemble of two guitars, a charango, quena trios, a concertina, and a violin. Rivera named his group Felipe V. Rivera and his Bolivian Orquesta Típica, although in some cases this name had slight changes or variations. Within the orchestra other subgroups would appear, such as quena and different vocal trios including Lolita Molina, Mecha Torrejón and Félix de Balois Leaño, three vocal virtuosos.

The sound of the instrumental ensemble in Rivera’s recordings is different from the one that prevailed from the 1960s onwards with Bolivian neo-folklore groups such as Los Jairas and Los Payas*.* The quena playing technique*,* for example, had not yet adopted the use of intensity vibrato, stacatto and the addition of a second quena taking on the role of a second voice, using thirds to the core melody. All these techniques and search for aesthetics would become the golden standard after the contributions of important woodwind performers such as Gilbert Favre, of Los Jairas, and Alcides Mejía, of Savia Andina. In Rivera’s recordings, “Linda Cruceña”´s quena plays a —barely audible— second voice to the core melody led by the concertina. The case of “Chongallapana” is indeed remarkable as one of the first songs recorded by Rivera´s ensemble, where two quena voices are played by thirds, with an emphatic use of glissando. However, both cases are exceptional.

The charango is ever-present in Rivera´s recordings, as it was in most ensembles and estudiantinas since the beginning of the 20th century (Sánchez Canedo 1992, 16). However, its role is still extremely limited, restricted to the accompaniment strumming (for example, in the second part of “Medianoche”). The experiences of charango players such as Mauro Núñez and Ernesto Cavour will allow this instrument to expand its technical, timbral and expressive resources. Nevertheless, “Amorosa palomita” bailecito —one of the first six songs recorded by Rivera in 1931—, contains a charango performance by “Indio” Caballero, who plays the plucking with superb sophistication. This performance, which explores new instrumental possibilities, does not come up in the orchestra´s later recordings.

Conversely, the guitar had already reached great prominence for the period. Its importance is explained by the fact that the playing technique recovers the traditional styles of the Creole guitar while expanding its possibilities to the bordoneo, or the playing of the bass strings in a melodic and rhythmic bass accompaniment. It was not unusual to find at least two guitars playing at the same time in Rivera´s orchestra: one would play the bordoneo and the other would provide accompaniment by strumming. One of the orchestra guitars carries a Rivera innovation: it has six double metal strings with traditional tuning. It is particularly interesting to listen to the yaraví and huayño “Lamento peruano” (Peruvian Lament) —or “Lamento del indio” (Indian Lament)—, performed by two guitars. In this song, following a “bordoneo” unison in the introduction, the first guitar leads the melody with a high-pitched plucking, while the other guitar accompanies with arpeggios and some subtle countermelodies. When the yaraví gives way to the huayño, the two guitarists show remarkable dexterity in their fingerstyle technique.

A requinto guitar usually embellishes the core melody of the two guitars, adding arpeggios in a higher octave. This instrument has a particular feature devised by Rivera: made from the shell of a gualacate, a large armadillo or tatú, it renders the guitar the appearance of a charango of considerable dimensions. The instrument’s sonority, which is sometimes mistaken with that of the charango, is present in many of Rivera’s songs, such as “El Socavón.”

The concertina —widely used in Bolivia and in the Cochabamba valley— is a recurrently used element in the recordings. The English who came to work on the railroads first introduced this instrument, developed in the first half of the 19th century in England. This instrumental base takes up the addition of a mandolin, a common instrument typical of estudiantinas (young university female students) at the time. The presence of a piano is audible in many songs, played with a remarkably simple technique. For his recordings in 1941, Rivera also refers to the use of a harmonium.

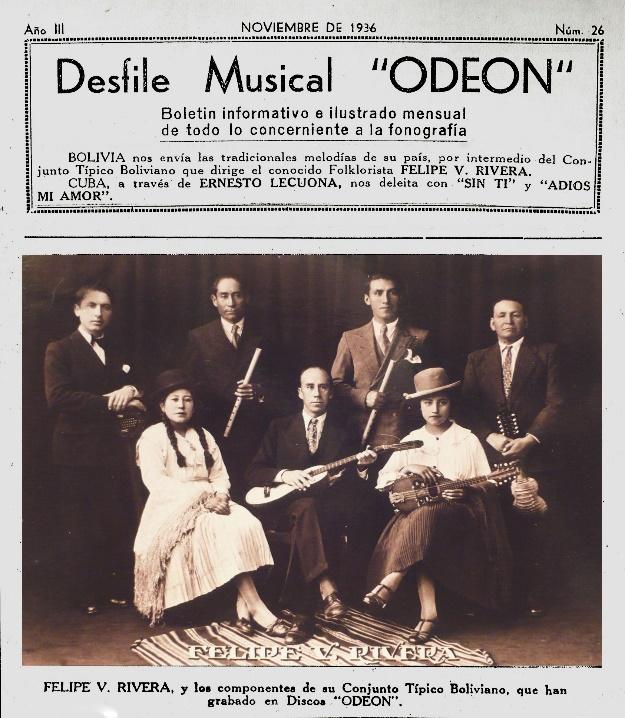

Odeon Newsletter number 26, 1936, advertising Cuban Ernesto Lecuona, Felipe V. Rivera and his Bolivian Típica (Ilda Rivera´s Collection).

The sikus or zampoñas were not part of the family of instruments commonly employed in creole music, as was the case with Rivera´s band or the estudiantinas of the first half of the 20th century. These instruments continued to be restricted to troops formation (or military bands) with percussion accompaniment. Although the 4th Company of the Loa Regiment had already recorded a repertoire with zampoñas in La Paz —introduced for the occasion as the Sampoña Orchestra [sic] in July 1917—, Rivera was the mastermind behind the first recording of a sikuris band. The event took place in Buenos Aires in April 1943, with ensuing performances in theatres and radio stations.

Rivera’s sikureadas are impeccably performed and masterful in their dynamics. We mention the case of “La Refinada,” a cueca, a typical creole genre, performed —nonetheless— with sikus. It is worth noticing the remarkable dynamics throughout the quimba —the refrain— in which the bass drum and snare drum stop playing and leave the sikus accompanied only by a triangle, to then bring in all the instruments in the jaleo, the cueca´s final outro or coda.

Rivera also ventured into the recording of anatas. He recorded a total of four anateadas with RCA Victor: three on January 11, 1938 —namely, “Los Alegres del Norte”, “Año Nuevo”, “Ay Florcita”—, and a last one on April 30, 1943 —“Condorcito”. In all these cases, instruments perform at the same pitch, accompanied by snare drum and bass drum.

Another key element in Rivera´s work can be traced in the carefully selected lyrics and the accurately measured stanzas, to which he granted significant relevance. In a letter to Ruiz Lavadenz (May 17, 1938) he speaks of the need for “artistic flair” (Ilda Rivera´s Collection) referring —among other things—, to lyric poetry. As mentioned before, Rivera sometimes incorporates his own verses in traditional songs to fit the structure of cuecas, bailecitos or huayños. Additionally, many songs in Rivera´s repertoire are in Quechua, such as the yaraví “Diusllaguan” (“Alone with God”), and some others in Aymara. It is not unusual to find the use of voices in both languages in most of the recordings, in the lyrics and in the added dialogues and coplas.

There is an extra salient feature in Rivera found in the picaresque dialogues that he inserts in each song, almost always preceding it. These original dialogues of his authorship depict a scene: a fiesta, a comparsa or an agrarian rite (for example, the marking of a herd of goats in the huayño “Kancharani”). In 1938, the dialogues appear in the recordings for the first time and become a signature trademark as of 1941.

The dialogues in cuecas, in bailecitos, in picaresque, and in mischievous huayñitos (called “humorísticos”) can convey jokes between a man and a woman. They are composed mostly in octosyllabic quatrains with assonant rhyme, in the style of coplas counterpoints. As initially mentioned, they describe a particular situation —as is the case at the beginning of “La Rotunda,” where two rogues see through the keyhole of a room to find out who is attending the party before they dare to enter the ballroom. Finally, it should be noted that always, in the intermission between the cuecas and the bailecitos, picaresque coplas are declaimed, possibly referring to one of the musicians in the orchestra or making a special dedication to a friend or relative.

The Truncated Project and Rivera´s Influential Work

Rivera made an additional 160 recordings in the 1940s. The Bolivian Orquesta Típica may have even come to record 74 songs in a single day in 1941, as the full ensemble did not have the resources to stay longer in Buenos Aires. This was quite a feat considering that most of the songs at that time had a complex and —to put it mildly— theatrical structure. They included dialogues, coplas and mischievous jokes at the beginning and in the middle of each song, as well as whistling, clapping and laughter. They are very vibrant experiences, of a naturalistic type, within the framework of festivities and celebrations.

Rivera passed suddenly in 1946. He was about to record 180 new songs. He did not live to see the technological transformation that would ensue, such as open reel recording and the appearance of vinyl and microgroove records. His work remained entirely captured on 78 rpm “shellac” records, which could only be listened to by those who kept adequate equipment for their reproduction —which led to their near extinction. However, these records did not vanish. The presence of this repertoire in the Argentine songs´ legacy is unmistakably apparent, hence the importance of Rivera´s pioneering work. The ethnographic work shows that his recordings impregnated the popular memory through oral tradition. The transmission of these songs by word of mouth, from one guitar to another, kept them alive in popular festivities in Jujuy and Potosí. Successive recordings made by many popular musicians attest to the validity of these compositions and compilations to date, even when their origin may be unknown. “La guitarra de Rivera,” one of his huayños, continues to vibrate, and live on the strings of other guitars, inviting us to dance.

Information on musicians like Rivera takes on primal importance and deserves to be better known. The repository can serve as a fundamental input for research and consultation by different possible interested parties, both in the field of research and from a social and cultural perspective. It is hoped that the rich-sounding and musical heritage in these phonographic records will be accessible to anyone who wants to know more about the life, work, cultural influence, and identity relevance of this musician from Bolivia.

References

Karasik, G. 2000. “Tras la genealogía del diablo. Discusiones sobre la nación y el Estado en la frontera argentino-boliviana. In Grimson. A. (ed.). Fronteras, naciones e identidades. La periferia como centro. Buenos Aires: CICCUS-La Crujía.

Rivera, F.V. 1945. El último Cancionero Boliviano. Third Volume. San Salvador de Jujuy: author´s edition.

Sánchez Patzy, R. 2015. Felipe v. Rivera. Un puente fecundo. Música andina en las fronteras. Buenos Aires: Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, Universidad de Buenos Aires and Ministry of Culture.

Sessa, M. 2009. Sikuris de Susques. Buenos Aires: author´s edition.

Ilda Rivera´s Collection

Radek Sánchez Patzy´s Collection

Some compositions by Felipe V. Rivera

The credits of each track have been transcribed as recorded by Felipe V. Rivera for their publication in 78 rpm records, and as registered at the Dirección Nacional de Propiedad Intelectual de Buenos Aires. We have respected the spelling used by Rivera to record titles, genres, and instruments, even though they may not coincide with today’s current usage.

“Condorcito,” pandilla de anatas. Felipe V. Rivera y su Tribu. Huaiño instrumental. RCA Victor 60-0292 B. Recording: April 30, 1943.

“Quita Pena,” cueca. Felipe V. Rivera y su Orquesta Típica Boliviana*.* Author: Felipe V. Rivera. RCA Victor 38407 A. Recording: January 11, 1938.

“No me olvides,” bailecito. Felipe V. Rivera Band. RCA Victor 39346 A. Singers: La Mecha [Mercedes Torrejón] and Félix B. Leaño. Recording: April 10, 1941.

“El Chapaco,” huaiño humorístico. Conjunto Felipe V. Rivera. RCA Victor 39012 B. Recording: May 3, 1939.

“Lamento peruano” [it also appears under the name “Lamento del indio” (Indian Lament).], yaraví and huaiñito. Felipe V. Rivera y su Orquesta Típica Boliviana*.* RCA Victor 38947 B. Performers: Daniel Pastor Miranda and Oscar Loayza. Recording: May 6, 1939.

“Esmoraca,” huaiño. Felipe V. Rivera y su Banda de Cicuris. RCA Victor 60-0411 B. Recording: April 6, 1943.

“Titicaca,” trote. Felipe V. Rivera y su Orquesta Típica Boliviana. Author: Felipe V. Rivera. RCA Victor 38611 B. Recording: January 11, 1938.

“La guitarra de Rivera,” huaiñito. Conjunto Felipe V. Rivera. RCA Victor 39346 B. Singers: La Mecha (Mercedes Torrejón) and Félix. B. Leaño. Recording: June 10, 1941.

“Chongallapana,” yaraví. Felipe V. Rivera y su Orquesta Típica Boliviana. RCA Victor 47683 B. Recording: May 6, 1931.

“Ley seca,” taquirari. Felipe V. Rivera y su Orquesta Típica Boliviana*.* RCA Victor 38873 B. Recording: May 6, 1939.

“Medianoche,” yaraví-huaiñito. Felipe V. Rivera y su Orquesta Típica Boliviana*.* RCA Victor 38892 A. Recording: May 3, 1939.

“El socabón” [El socavón], prayer and huaiñito. Conjunto Boliviano Felipe V. Rivera. RCA Victor 60-0179 B. Singers: La Mecha (Mercedes Torrejón) and Lolita (Dolores Molina). Recording: April 15, 1943.

“El tormento,” cueca. Felipe V. Rivera y su Orquesta Típica Boliviana. RCA Victor 39012 A. Refrain sung by trio. Recording: May 3, 1939.

“Domingo de carnaval,” pasacalle. Conjunto Felipe V. Rivera. RCA Victor 60-0281 A. Singers: La Mecha (Mercedes Torrejón) and Lolita (Dolores Molina). Recording: April 30, 1943.

“Kancharani,” huaiño. Felipe V. Rivera y su Banda Boliviana de Cicuris. RCA Victor 60-0087 B. [Compilation:] Felipe V. Rivera and D. P. Miranda. Recording: April 7, 1943.

![Felipe V. Rivera and his Bolivian Band of *Cicuris* \[sic\] in 1943, posing for a promotional ad for RCA Victor. Many *sikuris* came from different villages in the Chicheña and Lipeña regions, bordering Argentina (Ilda Rivera´s Collection).](/images/content/Sanchez-PatzyR001/image1_hufac4c6046fcf3ae3f01f6b05848d851a_180080_1110x0_resize_q80_lanczos.jpg)