Abstract

What “fractures” in a person when put under intense duress? What happens to us, and who we consider ourselves to be and are considered to be, under the conditions imposed by colonialism and dispossession. Does a person “lose” just their mind or is it their story that goes missing? Do they become an unknown victim of erasure, identity scattered across time, or is it only a hit to their sense of agency? The primary objective of this paper is to argue that there is an intrinsic interconnectivity of the mind (physiological and constructed), of a people’s sense of agency, of a people’s identity, of a people’s narrative capacity, and that this interconnectivity can be understood as a unifying “coherence”. While we are often content discussing agency, narrativity, and identity without the mind, and vice versa, I think we should be more attentive to the holistic nature of mind and self. This holism is where the need for a critical philosophical framework of MAIN (mind, agency, identity, narrative) coherence emerges. It is the goal of this paper to investigate the interconnective system of MAIN coherence I have sketched, and to process through its ruptures the uniquely damaging consequences of violent colonial dispossession.

Introduction: What matters to our survival? Coherence

“— what matters in survival is identity” (David Lewis, Survival and Identity)

It seems to me that David Lewis’s account of identity1, and thus of survival, reads as incomplete, insufficient, to all that we are and all that we carry as human persons.

There is a “death in life” that human persons can suffer that Lewis cannot account for. A case of this “death in life” can be found in the “kill the indian, save the man” sentiment underlying 19th-century acts of cultural genocide towards Native people in the USA. Despite people “surviving,” persisting through time with their “person-stages” relevantly connected and continuous (a must for Lewis), there is a critical absence in the account. Under the “kill the indian, save the man” policies of the US in the 19th century, people underwent an internal jumbling in time, and in place, that left them alive but unable to fully make sense of themselves in the world.

What Lewis’s theory of personal identity misses is a robust survey of what renders human persons whole, what makes them coherent. Survival requires identity in conjunction with several other elemental aspects of human persons to result in a type of unity. It is coherence that matters in survival. And it is my goal to convince you that this coherence consists of identity, agency, narrativity, and mind working in lockstep.

In this brief overview, I will:

1. Build a philosophical framework for coherence and its relation to survival, drawing from, and adapting, the psychological measure of “sense of coherence”.

2. Articulate the nature of “rupture” in the context of colonial violence and imposition.

3. Investigate how colonial rupture to coherence manifests in mere being instead of survivals of becoming.

1. Putting Together an Account of Mind, Agency, Identity and Narrativity (MAIN) Coherence

Sociologist Aaron Antonovsky’s “Sense of Coherence” (SOC) scale2 is used by psychologists to measure a person’s resiliency in the face of stress. In practice a psychologist will analyze respondents’ rankings of the comprehensibility, manageability, and meaningfulness of external stimuli and stressors in their surroundings. For coloniality and dispossession, applying a measure that assesses a person’s ability to cope with prolonged stress and trauma is advantageous.

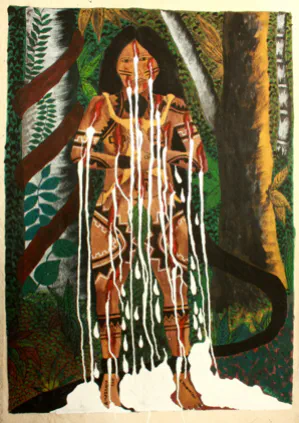

Mind

The mind, as dependent on our physical brain and its interactions with our environments and communities3, speaks to our inherent predisposition to extension. In facilitating our subjective experiences4 of the world, our minds take on a more holistic role. The mind is centrally important to the manageability of what we encounter in the world, both in our ability to cognize it and in our ability to physiologically (and psychologically) process it. The mind, when also taken holistically in an extended framework, rests upon our relationships not only with other persons, but with our environment more broadly.

Mind, illustration by Annan Timon

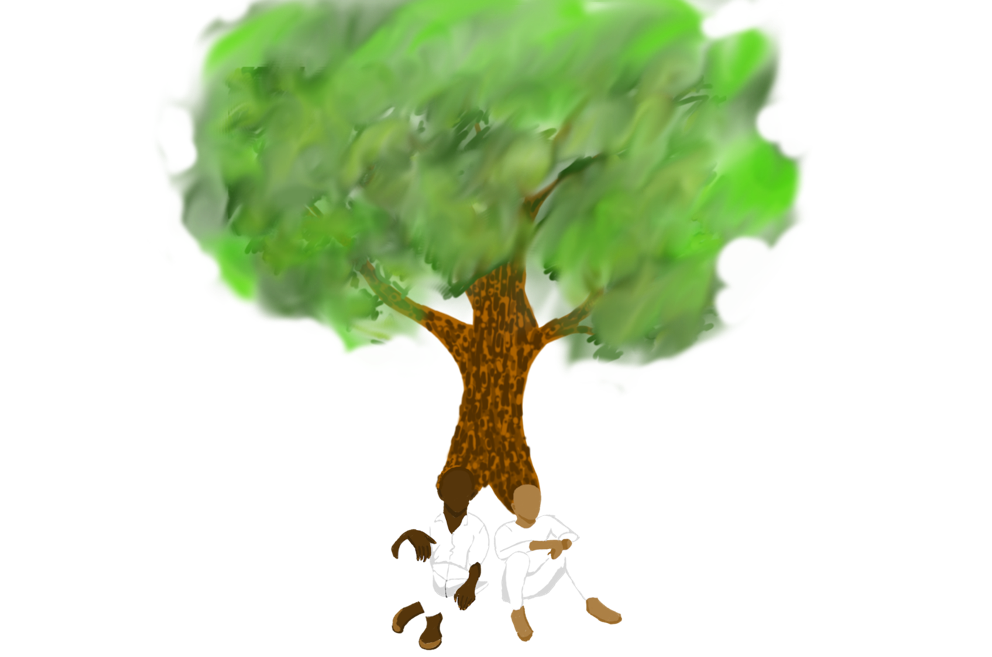

Agency

Agency refers to a person’s ability to consciously reflect upon their desires5 and beliefs, a person’s will to act, and a person’s capacity to plan their future actions6. Our agency is also a matter of the manageability of our encounters with our surroundings and our relationships. How manageable we rate a situation or a relation is tied to how confident we feel about our ability to act, and plan future actions, within it.

Agency, illustration by Annan Timon

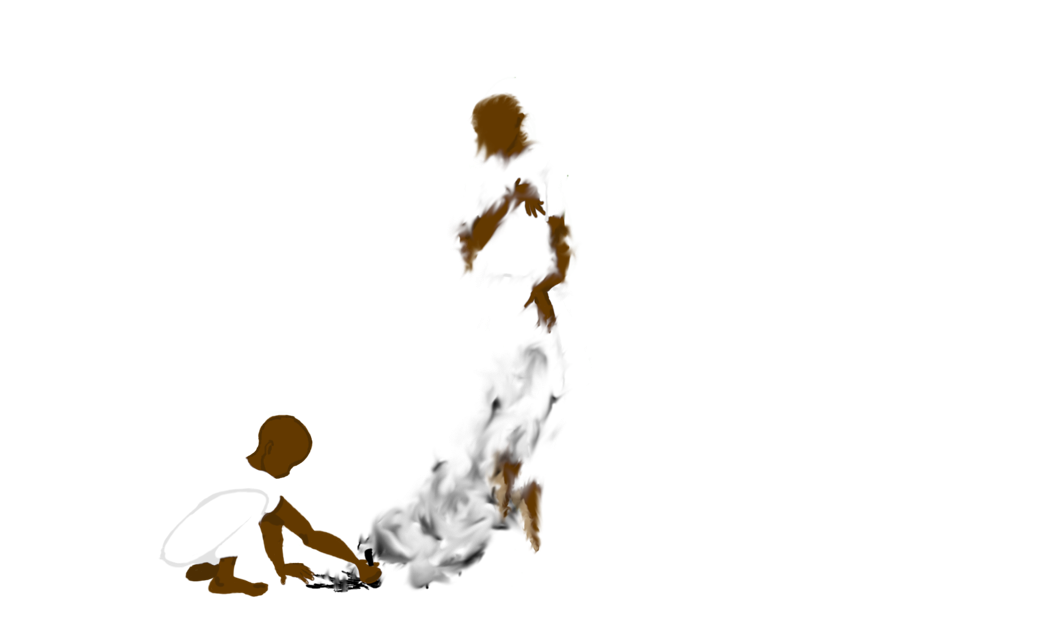

Identity

Identity lies between the metaphysical concept of “personal identity” and the more grounded concept of “agential identity.” We will reduce “personal identity” to the idea that what in us as individuals persists, remains constant and supposedly uniquely ours, through time. We define “agential identity”7, as the social relation in which a rational person is recognized and seeks to gain recognition as a member of a given social group. Importantly, the pursuit of this recognition by an agent is contingent upon their beliefs about themselves and societal beliefs about the characteristics that map to membership in said group. Our identity speaks to our comprehensibility. How we persist in time and how we are known to others through categories, is a matter of being understood in social relationships, and in our journey through life.

Identity, illustration by Annan Timon

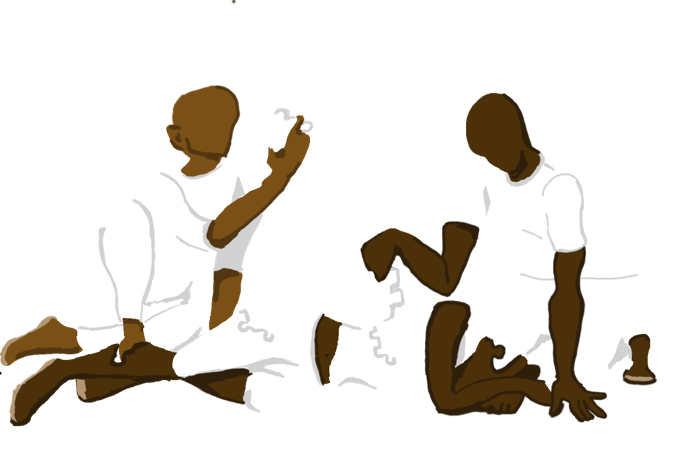

Narrativity

Narrativity builds on the idea of “sense-making”, or rather, of meaning-making. Here, narrativity maps to our capacity to derive meaningfulness from our experiences. As we weave together narratives, we do so in ways that make sense, make meaning, of all the relationships we hold in and with the world. The function of narrative goes beyond mere storytelling, and instead acts to bring out a unity between who we are8, who we see ourselves to be, and the world in which our formative experiences9 of being take place.

Narrativity, illustration by Annan Timon

To bring us back to a conversation of the body, it is important to understand how MAIN coherence is simultaneously contained within AND external to the individual body. Our minds, while heavily connected to our single self-contained brains, are easily affected by environmental and external social factors. Our agency, while “self-contained,” is dictated by external forces and material realities. Our identities, even when considered through a metaphysical lens, are nevertheless determined and play out under the influences of the world on our fleshy, finite forms. And our narrativity, despite being perhaps the most abstract link, manifests in the body as a way to position physical forms in place, in relation to the material world, through story.

It is when we attempt to pull apart MAIN coherence, to disrupt a unity of self in and of the world, that problems arise. And when we move to think that only one aspect of MAIN coherence is sufficient for survival, we come instead to occupy a position of death in life.

2. Articulating the Ruptures of Colonial Dispossession

In discussions of unity, we almost inevitably tumble into discussions of dissonance.

What is it for “wholeness” to rupture?

The central question becomes, what IS the rupture that colonialism inflicts, and how does it affect MAIN coherence?

Recall the genocidal phrase “kill the indian, save the man.”

What about Henry Pratt’s infamous declaration, and its implementation through policies forcing Native children into westernizing, “civilizing” boarding schools10 brought about rupture? Rupture in colonialism is a wound with many jagged edges. Colonialism not only removes people from relationships with their land but also dispossesses people from their relationships to knowledge and culture they hold with one another. In their bodily removal from place, there is an adjacent psychological (and spiritual) removal. Add to this bodily removal, the further forced erasure of heritage in boarding schools and severed connections to community. When the “native” alone is “killed” and the “man” is left, it is the Native person’s connections and relationships that are eliminated. While the physical body supposedly persists in time, there is a loss, a rupture, that transcends time and poses unique consideration.

The ruptures of colonial dispossession can then be articulated as the forced removal and isolation of human beings from their relationships with each other, their environment, and processes of knowledge production. This removal, these ruptures, will always inherently be bodily. But the nature in which the body is afflicted can differ drastically. The body is afflicted by colonial rupture through death, physical dispossession from land, and psychic dispossession from community, with all of these experiences entailing a felt violence.

Where understanding these ruptures takes on greater depth, is in the conversation about MAIN coherence and the SOC scale. In the rupture occurring in the “kill the indian, save the man” case, there is a multi-faceted harm occurring. On its face, there is psychological trauma, which is where an SOC assessment would be an adequate measure. But there is more than an individual psychological harm in the traumas of rupture in colonial dispossession. In the case presented, people are forced into full incoherence—not only within themselves and their immediate internal bodies, but within the greater contexts of the world.

The effects of colonial rupture on MAIN coherence are:

(M) An impact on the ability to recognize and manage the extension of mind into the environment (a dissolution of holistic mind).

(A) A limitation on an agent’s ability to plan for and manage their own future AND a restriction of an agent’s will (the prevention of freedom of movement and freedom to act).

(I) An inability to name oneself and one’s relationships within community and land outside of dominating colonial ways of knowing and naming; or rather, the inability to comprehend oneself and one’s relations to the world outside of colonial ways of knowing.

(N) Restrictions in the kinds of stories, and meaning, people are able to tell about themselves and the world. A forced indoctrination into a limited set of narratives.

It is then in the rupture, the splitting, of MAIN coherence itself that we see a harm of partials presented as wholes. Without an interconnected MAIN conception of coherence, those dispossessed by colonialism fall prey to a partial survival. If coherence is essential to the survival of whole human persons, then what comes in the partial survival is a sort of death in life. It is here that we can see a physical persistence without unity, and without the potential of becoming.

3. Questions of Being vs. Becoming, Differences in Survival given Colonial Violence

We have arrived at yet another pressing compound line of questioning.

How does the fragmentation of MAIN coherence from colonial rupture affect our survival?

What is the difference between mere persistence as a partial person and persistence with the possibility of self-determination?

It is through the investigation of these questions that we can come to understand the repercussions of coherence interrupted by colonial violence. Perhaps most importantly, in our investigation of this question we can begin to see the role of unity, and how unity becomes essential to “becoming” rather than mere being.

To answer the first question, the concepts of “death in life” and “social death”11 become critical. In the rupture of MAIN coherence, and its subsequent fragmentation, we arrive at a “survival” in partial.

Even if a dispossessed person is kept biologically alive, the forcible lack of coherence can mean that their narratives, their relationships with land (their mindedness extended in land), their agency to plan their future, and their identity can be forced to die at the hands of systematic colonial rupture. So, it is a “survival” only in the biological, immediate, individual body. It is a survival of mere “being.” This survival of being, is one where people exist in a state of petrification.12

With the answer to the first question in hand we come to the issue of the second question, and introduce the important distinction of being and becoming for those enduring incoherence from colonial rupture.

To persist as a partial person after rupture, is to survive in a state of mere ‘being.’ Though the body remains, the ability to act in and upon the world, and to be known, is drastically limited. To merely ‘be’ is to lack self-coherence. In ‘being’ alone there is a lack of malleability. To just ‘be’ after rupture, is to have your physical form move through the world with limited capacities to self-identify, self-name, self-narrate, etc.

To be able to cultivate and maintain a persistence of coherent personhood after rupture entails a potential of becoming. The potential of becoming allows those surviving colonialism to live dynamic lives. The colonized are not relegated to merely biological existences (men who have had the “indianness” stripped from them), but instead hold in their full MAIN coherence and the ability to engage with and co-create the world around them. Those who have the potential to become, despite colonial attempts at rupture, fragmentation, and erasure, have the potential to be full persons rather than “walking cadavers” who can only exist day by day. So, the persistence entailed by those who become is a persistence of spirit rather than the fleshy being alone.

The potential of becoming speaks to a people’s sense of self determination. Not content with merely being in a body, being reduced to several parts moved at the whim of colonial powers, those colonized peoples who defy rupture as an ultimate ending take up a project of becoming. This is to imply that those colonized can work through rupture to retake MAIN coherence and/or to re-initiate the interconnected processes of MAIN coherence given the new realities colonialism has brought forth. In the dynamism of becoming, there is a refusal to be kept stagnant and past-bound.

In becoming, the person’s body moves through its coherence to bring forth the possibility of a livable future. There is not just a survival, after all the blood of colonial rupture, but a survivance.13

Bibliography:

Antonovsky, Aaron. Health, Stress, and Coping. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1979.

———. Unraveling the Mystery of Health: How People Manage Stress and Stay Well. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1987.

Bateson, Gregory. Steps to an Ecology of Mind: Collected Essays in Anthropology, Psychiatry, Evolution, and Epistemology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000. https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/S/bo3620295.html.

Bratman, Michael E. “Reflection, Planning, and Temporally Extended Agency.” The Philosophical Review 109, no. 1 (2000): 35–61. https://doi.org/10.2307/2693554.

Churchill, Ward. Kill the Indian, Save the Man : The Genocidal Impact of American Indian Residential Schools. San Francisco: City Lights, 2004.

Dembroff, Robin, and Cat Saint-Croix. “‘Yep, I’m Gay’: Understanding Agential Identity.” Ergo: An Open Access Journal of Philosophy 6 (2019): 571–99. https://doi.org/10.3998/ergo.12405314.0006.020.

Frankfurt, Harry G. “Freedom of the Will and the Concept of a Person.” The Journal of Philosophy 68, no. 1 (1971): 5–20. https://doi.org/10.2307/2024717.

Frantz Fanon. The Wretched of the Earth. 60th anniversary edition. New York: Grove Press, 2021.

Lewis, David. “Survival and Identity.” In The Identities of Persons, edited by Amelie Oksenberg Rorty, 17–40. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1976.

Peressini, Anthony F. “There Is Nothing It Is like to See Red: Holism and Subjective Experience.” Synthese 195, no. 10 (2018): 4637–66.

Schechtman, Marya. “The Narrative Self.” In The Oxford Handbook of the Self, edited by Shaun Gallagher. Oxford University Press, 2011.

Vizenor, Gerald Robert, Survivance: Narratives of Native Presence. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008.

David Lewis, “Survival and Identity,” in The Identities of Persons, ed. Amelie Oksenberg Rorty (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1976), 17–40. ↩︎

Aaron Antonovsky, Health, Stress, and Coping (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1979). ↩︎

Gregory Bateson, Steps to an Ecology of Mind: Collected Essays in Anthropology, Psychiatry, Evolution, and Epistemology (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000). ↩︎

Anthony F. Peressini, “There Is Nothing It Is like to See Red: Holism and Subjective Experience,” Synthese 195, no. 10 (2018): 4637–66. ↩︎

Harry G. Frankfurt, “Freedom of the Will and the Concept of a Person,” The Journal of Philosophy 68, no. 1 (1971): 5–20, https://doi.org/10.2307/2024717. ↩︎

Michael E. Bratman, “Reflection, Planning, and Temporally Extended Agency,” The Philosophical Review 109, no. 1 (2000): 35–61, https://doi.org/10.2307/2693554. ↩︎

Robin Dembroff and Cat Saint-Croix, “‘Yep, I’m Gay’: Understanding Agential Identity,” Ergo: An Open Access Journal of Philosophy 6 (2019): 571–99, https://doi.org/10.3998/ergo.12405314.0006.020. ↩︎

Marya Schechtman, “The Narrative Self,” in The Oxford Handbook of the Self, ed. Shaun Gallagher (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011). ↩︎

Paul Ricoeur, Time and Narrative, vol. 3 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988). ↩︎

Ward Churchill, Kill the Indian, Save the Man: The Genocidal Impact of American Indian Residential Schools (San Francisco: City Lights, 2004). ↩︎

Jana Králová, “What Is Social Death?” Contemporary Social Science 10, no. 3 (2015): 235–48. ↩︎

Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, 60th anniversary ed. (New York: Grove Press, 2021). ↩︎

Gerald Robert Vizenor, Survivance: Narratives of Native Presence (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008). ↩︎