What Is a Map?

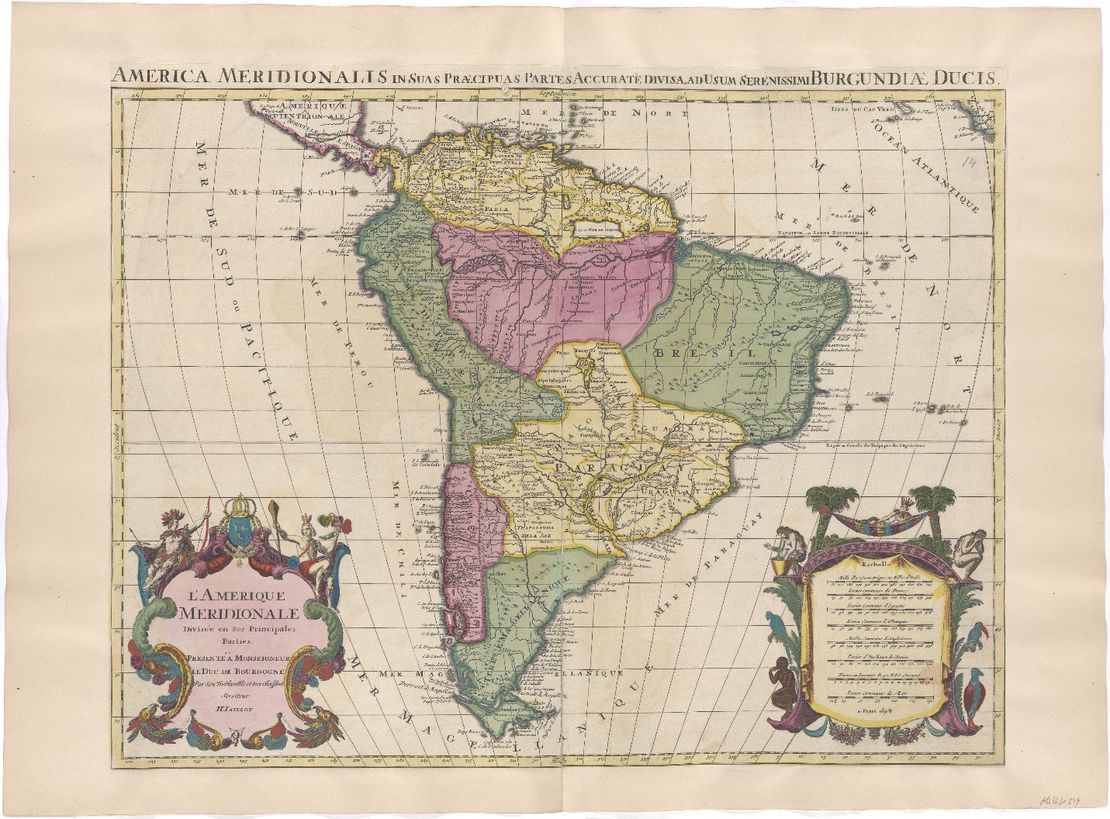

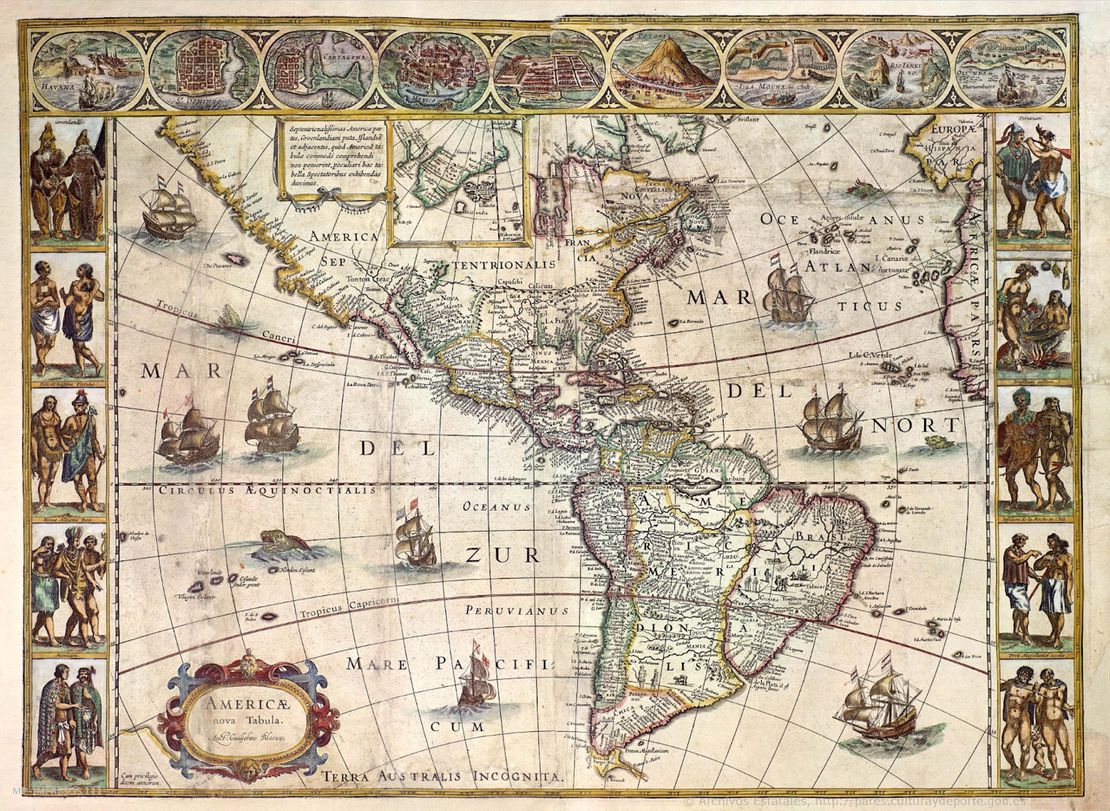

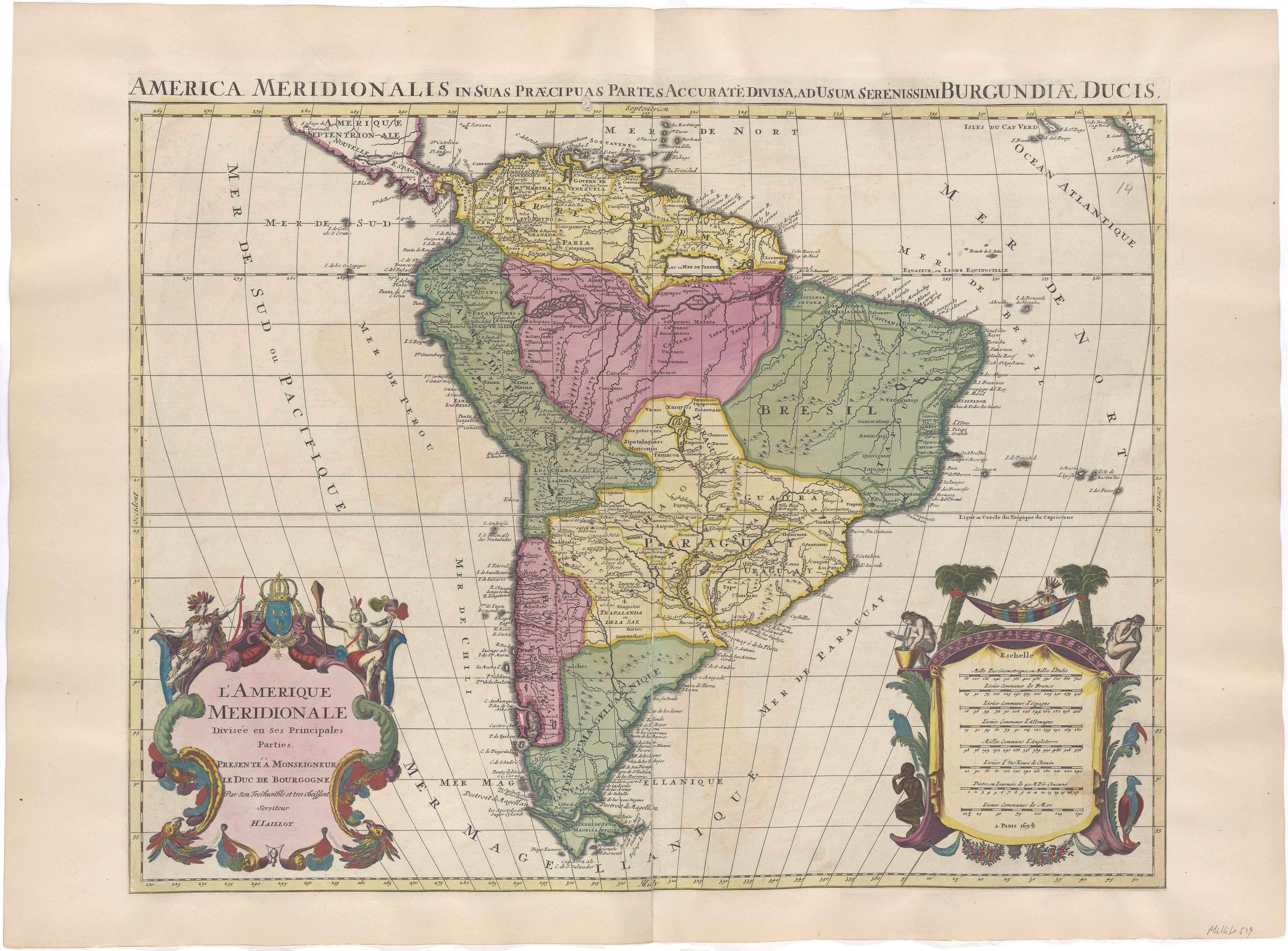

Often, we hear that a map is a representation of the Earth on a flat surface, and while that is entirely true in most cases, there is much more to maps than meets the eye. Maps are, above all, the visualization of a certain point of view: one that highlights certain features of the world and occludes others. Think about a subway diagram of a major city. We will find no reference to the bus system there, but that doesn’t mean that buses are not running, or did not exist at the moment the map was made. We should keep in mind that maps, just like books and paintings, have authors, are created in different cultural contexts and, more importantly, are made to serve a purpose.

Whether that purpose is identifying the location of buildings or services, or something less neutral, such as the maps of social happiness levels according to country, maps always have an agenda. This agenda may not be so evident at first glance, it may even contradict what the map is explicitly saying through its title, so we must beware of jumping to easy conclusions when consulting these documents. On this site, you will find maps that represent the surface of the Earth on a planar surface, but these maps also show, hide, and convey so many more messages. We have selected these maps because they depict Indigenous and/or Afro-descendant Peoples of the Americas and their forms of territorial occupation, most often as seen by others. Keep in mind that some people across time and space have not always used maps like the ones in this collection, since they had different ways of guiding relations in space. Over time, Western knowledge has privileged cartography - “the science of princes’’, born in the dawn of Imperialism - as the ultimate way of representing space, resources, itineraries and distances, but we should understand that oral memory, tales, songs, and intimate knowledge of environments can also guide people of a given space as effectively as any map would do. One final thing to consider when looking at a map, you should always wonder: What is this map trying to show me? And why? (See our map collection methodology).

How Do Maps Age?

Like any other cultural object, maps age, and occasionally, they don’t age well. Sometimes the places they represent no longer exist as such, as is the case for WWII maps and the aftermath that brought several changes to Eastern Europe’s political divisions. This is the case too for colonial maps, which visualize political entities with borders, such as viceroyalties, that no longer speak for the present-day configurations of those terrains. If we go back in time enough, we will also find images that differ greatly from what we think today as our world map. Mind you, people in the 1500s did not have GPS, and folks who were map makers probably couldn’t have visited or even obtained accurate information of all the regions they attempted to represent. In time, and due to technological advancements, the success of the imperial projects and the prevalence of Western knowledge, maps became more and more accurate in terms of geospatial location. But this is only one way in which maps of the past can be inaccurate.

When consulting these documents, we must understand that maps incessantly reproduce the culture that gave them origin. That means that whatever was valid for the cultural context of the map makers, the image will tag along to the present. Say we are talking about a map of colonial Spanish America that depicts an Indigenous reduction. Most likely, this image contains and reproduces all the prejudices, false assumptions, and demeaning idealizations that many conquistadors held about the Indigenous and Afro-Indigenous Peoples of the Americas. One must be attentive to the use of terms that are degrading to native groups, such as “Indios”—due to the conquistadors’ mistakenly believing they had arrived to India—, “barbarians”, “savages”, “enemies”, “infidels”, and so on. It also means that we might find the word “desert,” implying uninhabited lands, on a place where in fact many people lived, just because the map makers didn’t consider them lawful inhabitants, or because they wanted to occupy the lands themselves. These maps could also contain drawings that are in some way demeaning, or inscriptions that qualify native’s actions, lifestyles, and ontologies as anything less than worthy of existence. These and other notions circulated in the common sense of past societies, had concrete, material and symbolic effects over the lives and futures of many individuals and Peoples. Their inclusion on the map, if nothing else, can provide us with clues to understand why and how native groups have differential representation in these documents, while also pushing us to consider the complexities of their resistance. Like so much of our history as humans, some of these documents can be uncomfortable to look at in the present, but engaging with them in an educational way can broaden our understanding about past inequalities that directly impact our present and futures.

Whose Map Is It Anyways?

Authorship is always controversial when one talks about maps. Who made the map? The cartographer who signed it? The workshop that stamped it, where many people worked? The drafter who drew it? The illustrator who painted it? The corrector of the final version? The people who ordered its making? The company that paid for it? The researchers who gathered the information for the map to be created? The explorers who took notes about the river courses, the elevations and borders? Maybe the other people, those who traditionally inhabited the land and are the original guides of any in-land excursion? Simply put, it’s never a straightforward answer. Maps consolidate an enormous amount of knowledge, and hence, indicate the enormous amount of power that was put to work to obtain that knowledge. Particularly when we are considering maps that represent Indigenous peoples to some extent, we should be prepared to find their authorship occluded, until very recent years.

Colonial and early republican maps very rarely acknowledged the intervention of Indigenous authorship - some exceptions to this are native Codices and pinturas - but we know that Indigenous Peoples participated actively in the making of these documents. How do we know? Oftentimes, maps are the prelude or the consequence of some other administrative record that, in writing, will admit as a minor detail, facts like the guiding of an Indigenous person through the unknown lands. In the case of expeditions to lands that conquerors and settlers did not know, it is safe to assume that, coercively or forcefully, Indigenous individuals were part of these enterprises, and many times, it was thanks to their knowledge that colonial expeditions could safely reach these destinations in the first place. When the conquest and colonization of the Americas began, all the imperial powers together did not amount to a number that would overpower the number of native peoples of the Americas. Despite the common underestimation of their traditional knowledge that we might find in other accounts, conquerors needed Indigenous and Afro-Indigenous peoples to construct colonial cities and roads from the ground up, and map making was a part of this enterprise. Indigenous peoples had the knowledge that is concentrated and represented in these maps, and if they are not the official authors, it is only because they didn’t have the power to claim authorship.

Why Are These Maps Important?

If maps are always an exercise in choosing which information to include, so too is a collection of maps. This is a larger scale selection of the millions of maps you might find in different online and offline archives, in manuals, museums, shops, in art, and fiction. We have designed this collection to address one particular, structural situation, but recognize that there could be many others to be addressed. These maps are important because they make visible what was hidden for so long: the Amerindian territories have been, are, and will be inhabited by many different Indigenous and Afro-Indigenous peoples.

Despite all historical and/or present efforts to undermine their longstanding vitality, creative resistance to the processes of dispossession and rightful traditional land rights, the Americas are Indigenous land, from top to bottom. Like many other resources you will find in this website, maps are here to carve out a space where processes of Indigenous dispossession and repossession are discussed in light of historical and present-day evidence. We have compiled these maps to visualize diverse forms of occupations, a broad spectrum of groups, and as many territories as we could comprehend. This collection is no way final, and it is imperfect and incomplete and will continue to grow overtime. As with any other research that is interested in the experiences of groups of people who were subalternized into the social, legal, and political structures of other groups, the road that leads to valued information about these groups in the past is never straight forward. Reading against the grain, and counter reading these maps are some of the strategies that we employed to craft this selection and write commentaries on some of the maps. We encourage you to find different messages in these maps, hidden meanings, and outspoken truths. Our effort aims to center the native experiences that were represented in cartographical records, as a way of visualizing the trans-epochal significance, persistence and impact of Indigenous lives on Amerindian territory. As we navigate the rise of anti-Black, and anti-Indigenous hate crimes and discourses, these efforts are more important than ever.