Abstract

On May 23, 1649, in the pueblo of Ámbar, 210 kilometers northeast of Lima, the widow Doña Juana Flores dictated her final testament.1 A Quechua noblewoman of the Guacas ayllu, Doña Juana was wealthy and well-connected, as evidenced by the elite Indigenous men of Ámbar present during the transcription of her testament, including community leaders like Don Cristóbal Chaupis, Don Martín Naupari, and Don Martín Pilco Quispi.2 Doña Juana’s testament not only affirmed her wealth but also showcased her generosity. She left many valuable possessions to relatives and community members within and outside her ayllu, including fine textiles, silver utensils, a house, and multiple herd animals such as llamas and sheep. Following the Spanish notarial formula that was customary by the mid-seventeenth century, she honored the church of Ámbar, funded masses for her soul, bequeathed all of her worldly belongings, and devoted her soul to God.3 However, in a notable departure from customary Christian Iberian death practices, Juana’s testament includes a unique final request. She ordered that one of her “Castilian sheep” and its lamb be laid upon her grave on the day of her burial “as an offering.” Four months later, in early September 1649, Juana passed away. A note in the margin beside her request, written by the Indigenous notary Don Juan León Ticciatoc, confirms, “The offering was given.”4

As a member of the Indigenous nobility raised under Spanish colonial rule in Perú, Juana was versed in both Iberian and Andean cultural practices. In this instance, her public request for an animal offering upon her burial was based on pre-Iberian Andean death practices. However, instead of requesting a llama, an animal native to the Andes, as would have been customary for the Andean elite before Spanish colonization, Juana chose a “Castilian sheep” and its lamb—an introduced species with long-held symbolic value within Christian ideology and Iberian agricultural life.5

Juana’s burial request is a powerful case study because it takes place in 1649—more than a century after the forced displacement and demographic decline of Indigenous communities due to the onset of Spanish colonial rule and widespread adoption of Catholicism in the Andes.6 Doña Juana’s request for a burial offering can therefore be viewed as a microcosm of the broader transformations in Andean conceptualizations of and relationships with the natural world and the divine throughout the seventeenth century.7 This paper contextualizes Doña Juana Flores’ request for an animal burial offering—seemingly at odds with her identity as a Christian Quechua noblewoman—in order to illustrate the persistence of Andean cosmologies regarding the natural world despite their hemispheric convergence with Iberian religious, cultural, and agricultural practices.8

A Burial Offering

Animal offerings at burials were not common in Europe following the Council of Trent (held from 1545 to 1563), and missionaries coming to the Andes continued to standardize burial practices there in an effort to align with this European precedent. Therefore, Juana’s request for an animal offering at her burial demonstrates that her Christianity was informed by more than just the local friars of Ámbar.9 To fully contextualize Juana’s burial request, it is necessary to understand the foundations of Andean cosmologies and religious practices.

The multi-faceted, embodied divinity of wak’as/huacas was, and remains, Central to Andean cosmologies. “To say that an object or place was [wak’a] implied that it was sacred and deserved reverence.” Early Spanish missionaries struggled to conceptualize the divinity of wak’as, as these entities take the form of “small figures…, peaks of mountains, important places, shrines, ancestors’ bodies…, or burial sites.” Wak’as exist as “present embodiments” of the divine “in natural, petrified forms” that connect Andean communities to a shared past.10

According to traditional Andean religious beliefs, in the beginning times, before the creation of mortal humans, the Andes were home to formidable god-persons (wak’as/huacas). As creators of the world, once these divine beings fulfilled their purpose or were bested by more “crafty or powerful” wak’as, they turned to stone in their bodily form or took the shape of other natural phenomena. Despite their transformations, wak’as became increasingly omnipotent as their human descendants continued to honor their eternal powers. As permanent features of the landscape and “living forces that remained ‘integrated’ in the world of their people,” wak’a ancestors watched over their descendant ayllus. Andeans understood the physical landscape as a manifestation of wak’as’ “guiding influence” and past deeds. The Quechua word for place or village, llacta, translates to “a triple entity”—one that forms from the convergence of an ancestor wak’a, its resting form, and “the group of people whom the [wak’a] engendered.”11

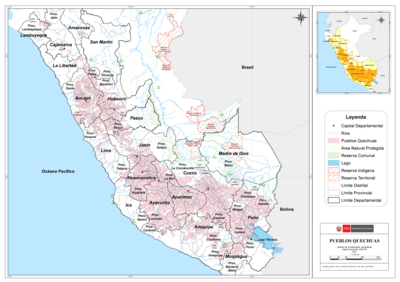

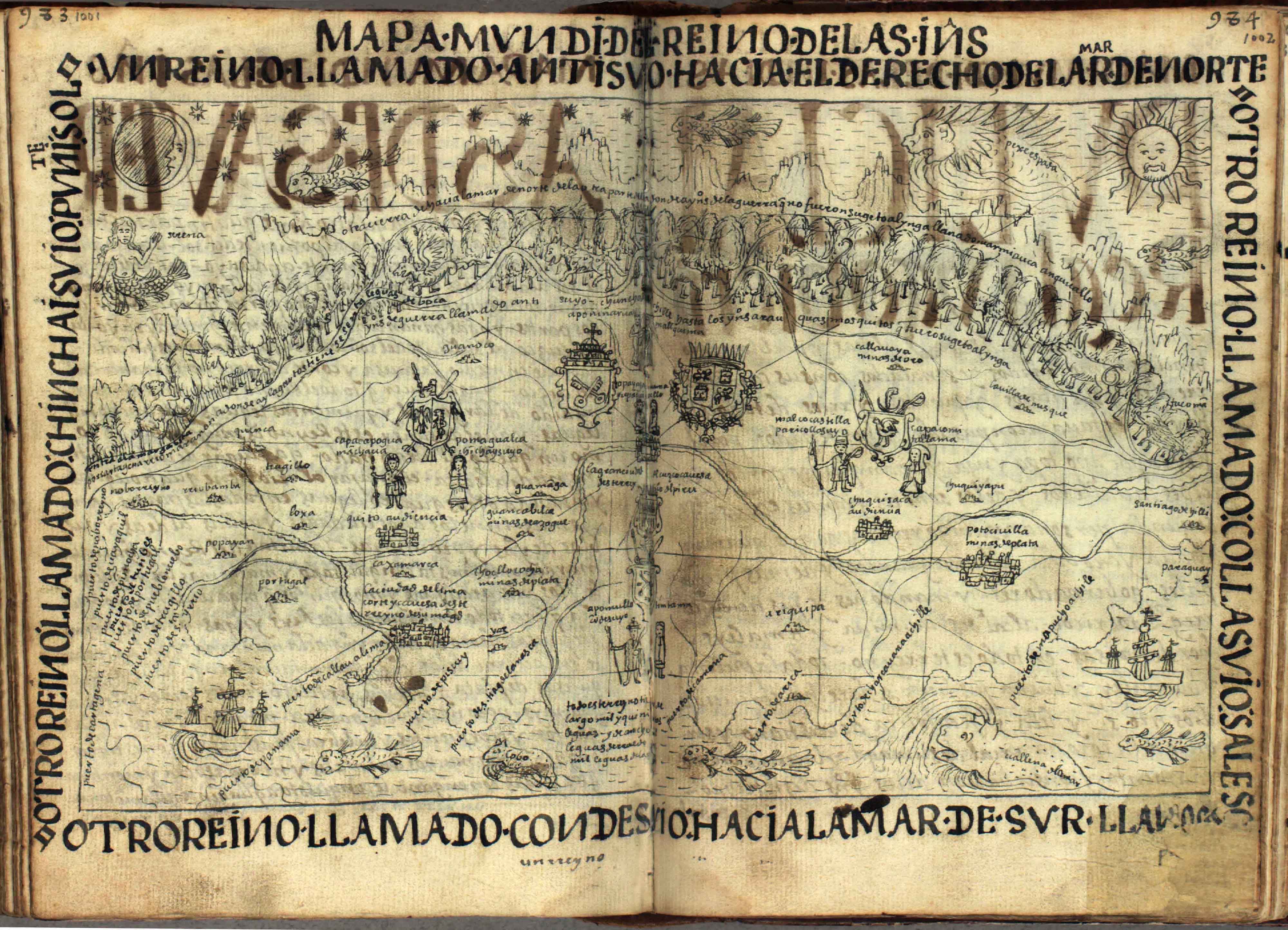

Andeans who understood themselves as descendants of a particular wak’a regularly provided offerings in exchange for “continuing support and guidance.” Chinchaysuyu, the northwestern part of Tawantinsuyu, was home to Juana’s ancestors.12 In 1615, Indigenous chronicler Guamán Poma de Ayala wrote that, before the arrival of the Spanish, the major wak’as of Chinchaysuyu included the Moon (Quilla), Venus (chasca cuyllor), lightning (chuqui ylla), and mountains such as Huarco and the Earth Maker (Pachacamac/Pacha Kamaq).13 These wak’as regularly received offerings such as guinea pigs (cuys), precious stones (uakari), seashells (mullo), maize (sara), coca leaves, corn beer (chicha), and llamas.14

To the dismay of Christian missionaries and the Roman Catholic Church, the “total” conversion of Indigenous communities and the “complete… extirpation of idolatry” from the Andes never came to fruition. Despite the Church’s extensive efforts to destroy Andean religious practices starting in the 1530s, in 1652—just three years following Doña Flores’ passing—Church officials still worried about the “persistent” veneration of wak’as across the Andes.15

Doña Juana’s request for an animal offering to be made upon at her burial—as was customary for the Indigenous elite prior to Spanish colonization—indicates that her worldview was as much Andean in practice as it was Iberian on paper. While her testament publicly affirmed her status as a Christian Quechua noblewoman, her request for an animal burial offering reveals that her understanding of the world remained deeply rooted in her Andean upbringing. Her decision to uphold this tradition serves as a testament to the inextricable bonds and interdependencies between Indigenous people and the natural world—connections that long defined, and continue to define, life in the Andes.16

The foundations of Andean society have long been based on principles of reciprocity and care. Anthropologists Bruce Mannheim and Guillermo Salas Carreño highlight that central to these principles in the Andes, both historically and today, is “food circulation and cohabitation” among all community members. This includes reciprocity between peers, parents and children, “people and their herds, people and their fields,” and between people and places more generally. In the Andes, “all social beings,” including mountains, rivers, plants, and animals, have always been “attributed thoughts, capacities of action, emotions, and intention.” These beliefs encompass the veneration bestowed on wak’as.17

Even accounting for the integration of Christian ideologies into daily life, food was and remains “the substance that constitutes and relates Quechua bodies.” Andeans like Juana related to others, both human and non-human, “through food sharing and continuous cohabitation.” This means that Andeans cohabitate with their physical environment in an interdependent relationship based on care. Juana was shaped by the Andes, with its snowy peaks and green valleys. She was formed by her relationships with the land of Ámbar throughout her life “through the provision of care and food as part of a wider process of continuous cohabitation.”18 This bond of cohabitation required that Juana nourish the land that had sustained her.

Endings as New Beginnings

Despite her public expression of devout Christianity, Doña Juana’s request for an animal offering reveals a more complex narrative. This burial request, which incorporated Indigenous Andean religious practices, occurred over a century after the onset of Spanish colonial rule, the subsequent state-led relocation of Indigenous groups through the Reducción general de los indios, and the widespread adoption of Christianity in the Andes.19 The Quechua noblewoman’s decision to request an animal offering underscores the survival of Indigenous relationships with the natural world that informed her relationship with place, particularly in and around Ámbar. In the Andes, each person derives sustenance, resources, and life from their birthplace, making it essential for Indigenous people like Juana to “renew [this relationship] routinely by feeding… a particular, named place.” This practice necessitated that “every request, cure, or plea to the places… [had] to be accompanied with food.” Juana’s reverence for both her wak’as and the Christian God is reflected in her burial offering, which acts as a “preparation and deliverance of food offerings” to maintain her relationship with the divine.20 As these places provided for and nourished her, Juana, in turn, fed and cared for them. Her burial offering of a ewe and its lamb upon her grave can thus be interpreted as her fulfilling her duty of offering food in reciprocity to the sacred places in which she lived. In her final gesture of gratitude for Pachamama, or Earth Mother, Juana’s final act of reciprocity facilitated her transition into the next world, hanan pacha.21

References:

Primary Sources:

Ávila, Francisco de. Relación de la idolatría de los indios de este Arzobispado de los Reyes que sea descubierto y diversidad de ídolos que adoran. 1611. Archivo General de Indias, Lima. AGI LIMA 301, L1.

Guamán Poma de Ayala, Felipe. Nueva corónica y buen gobierno [1615], edited by John V. Murra, Rolena Adorno, and Jorge L. Urioste. Madrid: Historia 16, 1987.

Jaffary, Nora E., and Jane E. Mangan. “Women’s Wills (Potosí, 1577 and 1601; La Plata, 1598 and 1658).” In Women in Colonial Latin America, 1526 to 1806: Texts and Contexts, edited by Nora E. Jaffary and Jane E. Mangan, 30–31. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 2018.

Lobo Guerrero, Arzobispo de Lima Bartolomé. Expediente de la Extirpación de Idolatría de los Miserables Indios que Fueron Hallados Tal y Conforme Estuvieron en la Gentilidad Cuando se Conquistó Este Reino y Pueblo de la Concepción de Chupas. 1614. Archivo General de Indias, Lima. AGI LIMA 301, L1.

“Testament of Doña Juana Flores, Ambar, Peru, 1649.” In Dialogue with Europe, Dialogue with the Past: Colonial Nahua and Quechua Elites in Their Own Words, edited by Justyna Olko, John Sullivan, and Jan Szemiński, 201–215. Denver: University Press of Colorado, 2018.

Villagómez Vivanco, Arzobispo de Lima Pedro de. El Pe. Fray Francisco de Lugares del orden de predicadores, que es el visitador que anda en las doctrinas de su religión, a hallado muchos ídolos, y adoratorios, supersticiones y errores, ha acudido a su remedio, y aunque a hecho algunos borrones ligeros inadvertidamente... August 16, 1652. Archivo General de Indias, Lima. AGI LIMA 302, L1.

Secondary Sources:

Charney, Paul. “‘For My Necessities’: The Wills of Andean Commoners and Nobles in the Valley of Lima, 1596–1607.” Ethnohistory 59, no. 2 (2012): 323–350.

Flores-Blanco, Luis, et. al. “Reconstructing the sequence of an Inca Period (1470–1532 CE) camelid sacrifice at El Pacífico, Peru.” Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 41, (2022): 1–10.

Kellogg, Susan, and Matthew Restall, eds. Dead Giveaways: Indigenous Testaments of Colonial Mesoamerica and the Andes. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1998.

MacCormack, Sabine. Religion in the Andes: Vision and Imagination in Early Colonial Peru. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991.

Mannheim, Bruce, and Guillermo Salas Carreño. “Wak’as: Entifications of the Andean Sacred” In The Archaeology of Wak’as: Explorations of the Sacred in the Pre-Columbian Andes, edited by Tamara L. Bray, 47–74. Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 2015.

Mannheim, Bruce. “Southern Quechua Ontology.” In Sacred Matter: Animacy and Authority in the Americas, edited by Steve Kosiba, John Wayne Janusek, and Thomas B.F. Cummins, 371–398. Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks, 2020.

Miller, G.R. “Food for the dead, tools for the afterlife: zooarchaeology at Machu Picchu.” In The 1912 Yale Peruvian Scientific Expedition Collections from Machu Picchu: Human and Animal Remains, edited by Richard L. Burger and Lucy C. Salazar, 1–63. New Haven: Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University, 2003.

Mills, Kenneth. Idolatry and Its Enemies: Colonial Andean Religion and Extirpation, 1640–1750. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997.

Mörner, Magnus. The Andean Past: Land, Societies, and Conflicts. New York: Columbia University Press, 1985.

Mumford, Jeremy. Vertical Empire: The General Resettlement of Indians in the Colonial Andes. Durham: Duke University Press, 2012.

Murra, John V. Formaciones económicas y políticas del mundo andino. Lima: IEP, 1975.

Olko, Justyna, John Sullivan, and Jan Szemiński, eds. Dialogue with Europe, Dialogue with the Past: Colonial Nahua and Quechua Elites in Their Own Words. Denver: University Press of Colorado, 2018.

Ramírez, Susan E. Indian-Religious Relations in Colonial Spanish America. Syracuse: Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs, Syracuse University, 1989.

Ramírez, Susan E. To Feed and Be Fed: The Cosmological Bases of Authority and Identity in the Andes. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2005.

Valdez, Lidio M., Katrina J. Bettcher, and Marcelino N. Huamaní. “Inka Llama Offerings from Tambo Viejo, Acari Valley, Peru.” Antiquity 94, no. 378 (2020): 1557–74.

Patrycja Prządka-Giersz, Jan Szemiński, and John Sullivan, “Testament of Doña Juana Flores, Ambar, Peru, 1649,” Dialogue with Europe, Dialogue with the Past: Colonial Nahua and Quechua Elites in Their Own Words, eds. Justyna Olko, John Sullivan, and Jan Szemiński, (Denver: University Press of Colorado, 2018), 201–215. ↩︎

Ayllu is a Quechua term/concept meaning family, familial group, or larger kinship group; Prządka-Giersz, Szemiński, Sullivan, “Testament of Doña Juana Flores, Ambar, Peru, 1649,” 212; I use “testament” and “will” interchangeably despite the primary sources’ using the term “testamento.” In Spanish, testamento translates to mean testament or will in English. “A will can confer rights or ownership over real property or personal property and can also be used to appoint legal guardians, but only takes effect once the testator dies… and when a will only deals with personal property, it may be called a testament.” Nichole McCarthy, “Last Will and Testament.” Legal Information Institute. Cornell Law School, June 2020. ↩︎

Nora E. Jaffary and Jane E. Mangan, “Women’s Wills (Potosí, 1577 and 1601; La Plata, 1598 and 1658),” in Women in Colonial Latin America, 1526 to 1806: Texts and Contexts, edited by Nora E. Jaffary and Jane E. Mangan (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 2018), 30–31. ↩︎

“yten tengo una obeja de castilla con su cordero en poder de lorenso quispi mi compadre el de tarma mando que se trayga para poner en mi sepultura para la ofrenda [on the left margin: pussose la ofrenda].” (“Also, I have a sheep of Castile with her lamb in the custody of Lorenso Quispi, my compadre, the one from Tarma. I order it brought and put in my grave as an offering. [on the left margin: The offering was given.]” Prządka-Giersz, Szemiński, Sullivan, “Testament of Doña Juana Flores, Ambar, Peru, 1649,” 208.) ↩︎

Luis Flores-Blanco et. al., “Reconstructing the sequence of an Inca Period (1470–1532 CE) camelid sacrifice at El Pacífico, Peru,” Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 41, (2022): 1–10; G.R. Miller, “Food for the dead, tools for the afterlife: zooarchaeology at Machu Picchu,” in The 1912 Yale Peruvian Scientific Expedition Collections from Machu Picchu: Human and Animal Remains, eds. Richard L. Burger and Lucy C. Salazar, (New Haven: Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University, 2003), 1–63; Lidio M. Valdez, Katrina J. Bettcher, and Marcelino N. Huamaní, “Inka Llama Offerings from Tambo Viejo, Acari Valley, Peru,” Antiquity 94, no. 378 (2020): 1557–74; Guamán Poma de Ayala, Felipe, Nueva corónica y buen gobierno, [1615], eds. John V. Murra, Rolena Adorno, and Jorge L. Urioste (Madrid: Historia 16, 1987), 288 (290); 290 (292). ↩︎

Susan Kellogg and Matthew Restall, Dead Giveaways: Indigenous Testaments of Colonial Mesoamerica and the Andes (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1998), 2–9. ↩︎

Paul Charney, “‘For My Necessities’: The Wills of Andean Commoners and Nobles in the Valley of Lima, 1596–1607,” Ethnohistory 59, no. 2 (2012): 323–350, 326. ↩︎

Charney, “‘For My Necessities’,” 327–340; Kenneth Mills, “The Naturalization of Andean Christianities,” in The Cambridge History of Christianity 6: Reform and Expansion, 1500–1660, ed. R. Po-Chia Hsia (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 508–539. ↩︎

Justyna Olko and Jan Szemiński, “Nahua and Quechua Elites of the Colonial Period,” in Dialogue with Europe, Dialogue with the Past: Colonial Nahua and Quechua Elites in Their Own Words, eds. Justyna Olko, John Sullivan, and Jan Szemiński, (Denver: University Press of Colorado, 2018), 36–38. ↩︎

Kenneth Mills, Idolatry and Its Enemies: Colonial Andean Religion and Extirpation, 1640–1750 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997), 39–74, 42–46. ↩︎

Mills, Idolatry and Its Enemies, 39–74, 42–46. ↩︎

Tawantinsuyu is the Quechua term for the Inca Empire, meaning “the four parts together” or “the union of the four parts.” ↩︎

Guamán Poma de Ayala, Nueva corónica y buen gobierno, 262 [264], 263 (265); 265 (267); 267 (269). ↩︎

Guamán Poma de Ayala, Nueva corónica y buen gobierno, 267 (269); 271 (273); 278 (280); 280 (282). ↩︎

Francisco de Ávila, Relación de la idolatría de los indios de este Arzobispado de los Reyes que sea descubierto y diversidad de ídolos que adoran, 1611, Archivo General de Indias, AGI LIMA 301, L1; Arzobispo de Lima Bartolomé Lobo Guerrero, Expediente de la Extirpación de Idolatría de los Miserables Indios que Fueron Hallados Tal y Conforme Estuvieron en la Gentilidad Cuando se Conquistó Este Reino y Pueblo de la Concepción de Chupas, 1614, Archivo General de Indias, AGI LIMA 301, L1; Arzobispo de Lima Pedro de Villagómez Vivanco, El Pe. Fray Francisco de Lugares del orden de predicadores, que es el visitador que anda en las doctrinas de su religión, a hallado muchos ídolos, y adoratorios, supersticiones y errores, ha acudido a su remedio, y aunque a hecho algunos borrones ligeros inadvertidamente…, August 16, 1652, Archivo General de Indias, AGI LIMA 302, L1. ↩︎

Olko and Szemiński, “Nahua and Quechua Elites of the Colonial Period,” 36–38. ↩︎

Bruce Mannheim and Guillermo Salas Carreño, “Wak’as: Entifications of the Andean Sacred,” in The Archaeology of Wak’as: Explorations of the Sacred in the Pre-Columbian Andes, ed. Tamara L. Bray (Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 2015), 47–74, 58–61. ↩︎

Mannheim and Salas Carreño, “Wak’as,” 60–61. ↩︎

Jeremy Mumford, Vertical Empire: The General Resettlement of Indians in the Colonial Andes (Durham: Duke University Press, 2012). ↩︎

Mannheim and Salas Carreño, “Wak’as,” 60–61. ↩︎

Mannheim and Salas Carreño, “Wak’as,” 62. “As humans cohabit with places and receive [food from] and give food to them on a regular basis, it should not be surprising that Quechua people use kin terms to refer to the places that are important to them. For example, the apu, or mountain peaks, are called fathers (taytakuna) in sonqo (Paucartambo) (Allen 2002:49) or grandparents in Ocongate (Quispicanchis) (Harvey 1991:6). In a similar way, several experts in giving food to the places with whom we talked in Cuzco consistently said ‘dear father’ before the name of any mountain. So, too, with ‘Mother earth.’ As a Quechua woman from Sonqo explained to Allen in the 1970s, these kin relations are established through food: ‘We owe our lives to her… she nurses the potatoes lying on her breast, and the potatoes nourish us’ (Allen 2002:29).” ↩︎

![Felipe Guamán Poma de Ayala, “Sesta Calle \[the sixth age group\] / Coro Tasque, \[short-haired girls\] / Twelve years old / They serve their parents and community,” 225 (227), *Nueva corónica y buen gobierno*, \[1615\]. Edited by John V. Murra, Rolena Adorno, and Jorge L. Urioste. Madrid: Historia 16, 1987.](/images/content/OharaK001/image1_hu3c2a1a85ca11fa3b111374389f627ea8_729247_1110x0_resize_lanczos_3.png)