Abstract

What is the best way to provide health care to rural Indigenous populations who live far from health care centers? In the case of pregnant people, what strategies can improve prenatal care and reduce the illnesses that are transmitted from parent to child—such as Chagas disease, HIV, hepatitis B, and syphilis—which can have severe health consequences for both parent and newborn? To address these questions, members of our team travelled to the Great Chaco region in August 2019 and January 2023 to observe how health care is delivered to pregnant women through the use of mobile health units.1 This was part of a program where non-state health providers partnered with the provincial public health systems in three neighboring countries to provide prenatal care to pregnant women, most of whom are Indigenous.

The Context

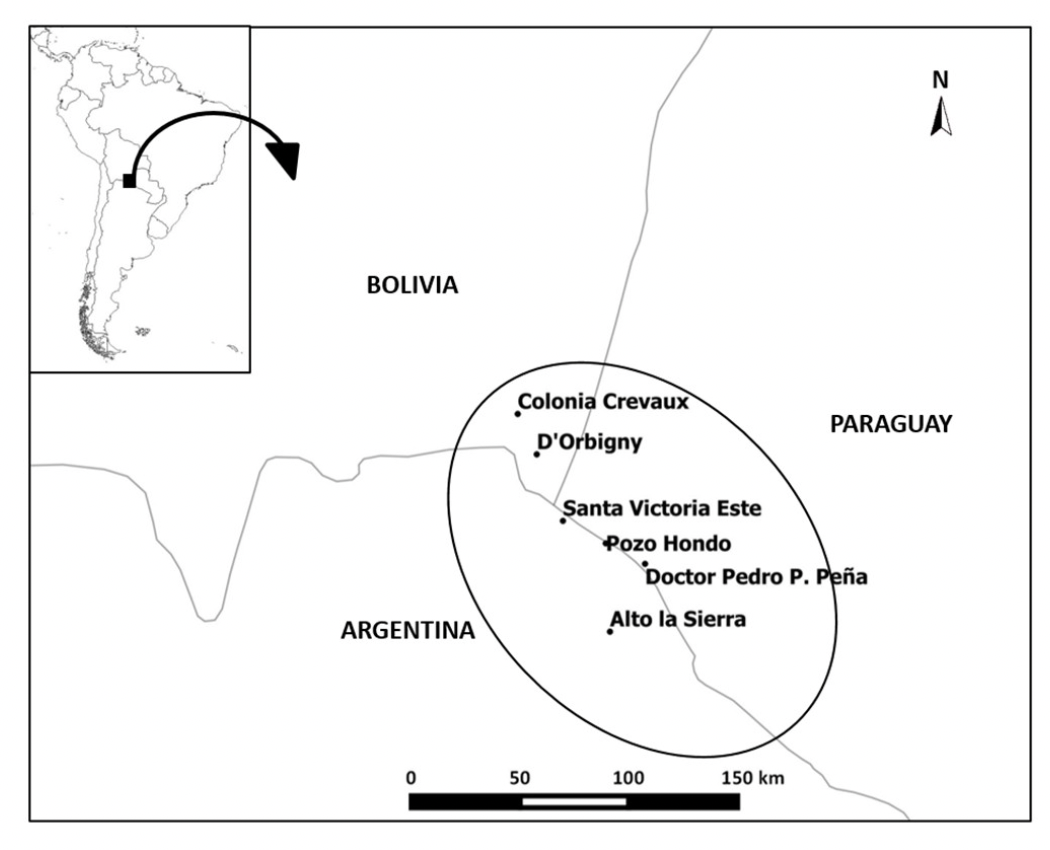

The tri-border area between Argentina, Bolivia, and Paraguay, in the Great Chaco region, is largely populated by Indigenous peoples. On the Argentine side, the Wichí are the largest ethnic group, followed by the Chorote and Pilagá communities, among others. The Weenhayek and Guaraní peoples are also present in the area, particularly in Bolivia and Paraguay, respectively. Mobile health units visited localities that included Santa Victoria Este and Alto La Sierra in Argentina; Crevaux and D’Orbigny in Bolivia; and Pozo Hondo and Dr. Pedro P. Peña in Paraguay (see Map 1). This region has some of the highest maternal and infant mortality rates in these countries, due in part to the scarcity of potable water during the summer (which leads to diarrheal disease and dehydration) and the prevalence of respiratory illnesses during winter. Accessing health care centers is often difficult due to distance, poor road conditions, and the extremely limited availability of cars in the Indigenous communities of the area. This increases the risk of untreated emergencies, sometimes resulting in death (see Table 1 in our related published article).

Map 1: Localities included in the ADESAR/Mundo Sano Intervention2

The local health post in Crevaux, Yacuiba, Bolivia. Photograph by Tulia G. Falleti, August 7, 2019.

Mobile Health Care

Since 2018, two Argentine non-governmental organizations (NGOs), ADESAR and Mundo Sano, have partnered with the province of Salta in Argentina, and periodically with regional health authorities in Yacuiba, Bolivia, and Boquerón, Paraguay, to provide prenatal care to pregnant women every other month. The team of NGO doctors—which includes an obstetrician, an ultrasound technician, a biochemist, and a pediatrician—partners with local health authorities (doctors, nutritionists, nurses, and community health workers) to provide health screenings to pregnant women. Each patient receives a clinical checkup, an ultrasound, and lab tests to screen for Chagas, HIV, hepatitis B, or syphilis. Moreover, when such illnesses are detected, the NGO doctors collaborate with local public health officials to provide treatment to the women and, when needed, to newborns. This care is provided at no cost to the women or the public health care system and is funded by the Mundo Sano Foundation through philanthropic funds and grants.

Ultrasound technician performing ultrasound using mobile unit; patient seated in pick-up truck’s front seat, La Abispa community in Salta, Argentina. Photograph by Santiago L. Cunial, August 2019.

Portable “lab” setup with rapid tests and mobile unit pick-up truck in the background, El Toro community in Salta, Argentina. Photograph by Santiago L. Cunial, August 2019.

What Were the Effects of Mobile Health Care after 18 months?

Between June 2018 and October 2019, the NGO doctors, using mobile health units equipped with an ultrasound machine and a portable laboratory stocked with rapid tests, made nine visits to the tri-border area. During this time, they were able to provide at least one prenatal checkup to nearly all pregnant women on the Argentine side of the border. They were able to do the same for about half of the pregnant women in the areas visited in Bolivia and Paraguay, where the doctors spent less time than they did in Argentina (see Table 3 in our article). In addition to administering prenatal care, the NGO doctors also diagnosed 69 cases of Chagas disease and five cases of syphilis; no cases of HIV or hepatitis-B were found among the women tested (see Table 5 in our article). Both access to prenatal care and rates of diagnosis improved with the introduction of mobile health units.

Coproduction in Health Care: Complementarity (yes) and Embeddedness (not really)

From a social science perspective, we evaluated this intervention as a successful case of coproduction between the NGO doctors and local health care authorities in delivering health care to pregnant women. “Coproduction” refers to a collaborative effort where both parties work together in a way that maximizes their respective contributions, thus improving the combined outcomes.3 In making our assessment, we searched for evidence of two key components of coproduction: (a) “complementarity,” where each party contributes skills or resources that the other lacks, and (b) “embeddedness,” which we define as the degree to which the parties are interconnected, learning from or transforming each other through their shared practices.4

In this medical intervention, there was complementarity between the NGO doctors’ expertise and equipment and the local health authorities’ knowledge and work, resulting in improved access to health care and diagnosis of disease. Nonetheless, we observed some areas for improvement, particularly the absence of a Wichí interpreter, which posed a significant communication barrier between patients and the medical team. On our second visit, however, we noted that having such an interpreter allowed women to discuss their personal circumstances and fears more openly. Many continued to seek out the interpreter for help navigating the health care system even after the medical intervention had concluded. In our article, we argue that while complementarity between NGO and public health care doctors is present, embeddedness—or a sense of rootedness with the patients and communities—is lacking, and an interpreter could improve this situation.

We also noted that, with the exception of community health workers in Salta (some of whom are Indigenous themselves), most doctors and health care professionals have very little interaction with Indigenous traditional care. Indigenous healers, such as curanderos (healers) or parteras (midwives), are either completely invisibilized or marginalized. We believe that an intercultural approach to health care—one that not only employs Indigenous language interpreters, but also incorporates curanderos and parteras, where available and willing to collaborate with traditionally trained doctors—could further enhance the outcomes achieved by this partnership. We are also eager to see how the implementation of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights ruling on the case of Lhaka Honhat (Our Land) Association v. Argentina, concerning the repossession of Wichí territory in this region, may affect individual and public health outcomes in these communities.

References:

Crudo, Favio, Pablo Piorno, Hugo Krupitzki, Analia Guilera, Constanza Lopez-Albizu, Emmaria Danesi, Karerina Scollo*, et al.* “How to Implement the Framework for the Elimination of Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV, Syphilis, Hepatitis B, and Chagas (EMTCT Plus) in a Disperse Rural Population from the Gran Chaco Region: A Tailor-Made Program Focused on Pregnant Women.” [In English]. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 14 (May 28, 2020): e0008078.

Evans, Peter. “Government Action, Social Capital and Development: Reviewing the Evidence on Synergy.” World Development 24, no. 6 (1996): 1119–32.

Ostrom, Elinor. “Crossing the Great Divide: Coproduction, Synergy, and Development.” World Development 24, no. 6 (1996): 1073–87.

To read more about our research, you can download our peer-reviewed, open access article published in World Development.

In our case study, we use the term “pregnant woman” rather than the more inclusive term “pregnant person,” because it specifically reflects the population that was treated by the doctors involved in this medical intervention. ↩︎

Favio Crudo, Pablo Piorno, Hugo Krupitzki, Analia Guilera, Constanza Lopez-Albizu, Emmaria Danesi, Karerina Scollo*, et al.* “How to Implement the Framework for the Elimination of Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV, Syphilis, Hepatitis B and Chagas (EMTCT Plus) in a Disperse Rural Population from the Gran Chaco Region: A Tailor-Made Program Focused on Pregnant Women.” [In English]. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 14 (May 28, 2020): e0008078, 4. ↩︎

Elinor Ostrom, “Crossing the Great Divide: Coproduction, Synergy, and Development,” World Development 24 (1996): 1073–1087. ↩︎

Our definition builds upon Peter Evans’ critique of the concept of coproduction. See for instance: Peter Evans, “Government Action, Social Capital and Development: Reviewing the Evidence on Synergy.” World Development 24, no. 6 (1996): 1119–32. ↩︎