Abstract

Without denying the violence perpetrated against Indigenous peoples and the high death rates of the so-called “War of the Barbarians” this essay aims to demystify the notion (present in historiography and primary sources) that Indigenous in northeast Brazil were exterminated. Until recently, in official documents and demographic censuses, some states in the Brazilian northeast denied the presence of Indigenous people, as was the case in Rio Grande do Norte and Piauí. In the analysis of archival documentary sources, however, we find alternative meanings of “extermination” being used during the “War of the Barbarians.” The term was sometimes taken to mean a forced movement to dispossess Indigenous people of their land and to use them as captives in other Brazilian captaincies, rather than a full-scale genocide as more commonly assumed. This essay contends that these wars functioned as a means of co-opting Indigenous labor and, above all, it seeks to dispel the idea that the Indigenous people in the region were all killed.In the second half of the 17th century, present-day northeastern Brazil saw several warlike conflicts between the Indigenous peoples who inhabited these territories and European colonizers who sought to push cattle ranching from the coast to the interior. The clashes began in the Bahian Recôncavo, around 1650, and soon spread to other captaincies, passing through the hinterlands of Pernambuco, Paraíba, and Rio Grande do Norte and arriving in Ceará between 1680 and 1720, as shown on the map below. In documentary sources, these conflicts are collectively referred to by the colonizers as the “War of the Barbarians,” a name also adopted within historiography.

Figure 2: Map of “The Northeast of Sugarcane and Cattle in the 17th century,” in Atlas Histórico do Brasil, translated into English by the author. Original version available at: https://atlas.fgv.br/marcos/caminhos-do-gado/mapas/o-nordeste-da-cana-e-do-gado-no-seculo-17

First of all, the expression “War of the Barbarians” should be problematized, foremostly because it applies the stigma of barbarism to Indigenous peoples. A secondary issue arises from the connotation, because they are “barbarians”, these peoples should be exterminated in this conflict. Such an implication should be challenged. In the excerpt below, a leading historian of this conflict, Pedro Puntoni, states that the war in the backlands of the colonial Northeast was a war of extermination and not a war to conquer workers:

“In the northern hinterland, on the contrary, for structural reasons having to do with the evolution of this economy and the colonizing process, far from being wars of conquest or wars to produce the submission of new workers suitable for cattle management, the wars against the Indians at this time tended to be wars of extermination, of territorial cleansing.”1

However, new research reveals precisely the opposite: Indigenous people were forced into colonial labor, and the idea of “extermination” had a different meaning. The minutes of the Junta das Missões de Pernambuco, as well as the letters, orders, and decrees issued by the governor of Pernambuco between 1712 and 1715, have been compiled in a book (below), and they provide clues for rethinking the idea of “extermination” in the context of the war.

Figure 3*: Minutes of the Junta das Missões de Pernambuco*, cover. National Library of Lisbon, Pombalina Collection, Cod. 115.

The Junta das Missões de Pernambuco was an institution created in 1681 by King Pedro II in order to expedite decision-making on issues of evangelization and the conquest of the Indigenous people of the colonial Northeast. The Junta met periodically in the presence of the governor of Pernambuco, his secretary, the bishop, and the other ministers and prelates. One of the Junta’s main tasks was to judge the justice of the war against the Indigenous people, as well as their captivity. In one of its orders, the Junta decided that (Figure 4):

“All males and females from seven years old upwards were to be captured and denaturalized. It was agreed that the Junta’s decision on captivity and extermination would be followed… to Rio [de Janeiro].”

Figure 4: Minutes of the Junta das Missões de Pernambuco, July 8, 1713. National Library of Lisbon, Pombalina Collection, Cod. 115, fl. 40v.

In another meeting of the Junta, four months before the above order of captivity and extermination (for Rio de Janeiro) was issued, the institution had already determined that these same Indigenous people involved in the war should be “deported” and that the women should also be “exterminated” (Figure 5).

“Reflecting on what was agreed in the Junta of September 5, 1712, about the banishment of the Tapuía Indians who made war on the whites and were taken prisoner, and doubting whether the women should be exterminated in the same way, it was decided that this should be the case.”

Figure 5: Minutes of the Junta das Missões de Pernambuco, April 3, 1713. National Library of Lisbon, Pombalina Collection, Cod. 115, fl. 36v.

In other words, at one point “extermination” is used as a synonym for “denaturalizing” and at another it is used as a synonym for “degredar,” but both have the meaning of territorial dispossession. In another letter, dated April 4, 1713, Félix José Machado, then governor of Pernambuco, informed the Captain Major of Rio Grande to comply with what had been agreed by the Junta: “that all the Tapuias of the Janduí, Capela and Caboré nations who had been caught in this war should be taken captive and exterminated in Rio de Janeiro” in the name of the common good and the good service of His Majesty.2

“Extermination” is more generally associated with the idea of destruction in a cruel way or elimination by death, as the historian Puntoni claims happened to the Indigenous people in the “War of the Barbarians”. However, another meaning, less popularly known, is the expulsion of a group from its territory or region. Notably, this last definition had already been given by the Portuguese lexicologist Rafael Bluteau in his 18th-century encyclopedia. For Bluteau, “extermination” was understood as “banishment, expulsion from one’s own land, one’s homeland, one’s residence. The destruction as a result of which extermination comes, or the departure of citizens from cities”. Following Bluteau’s definition, “extermination” could mean: “To throw out of the terms, limits, radii of some province, city, to banish, to exterminate the Turk from his states.”3

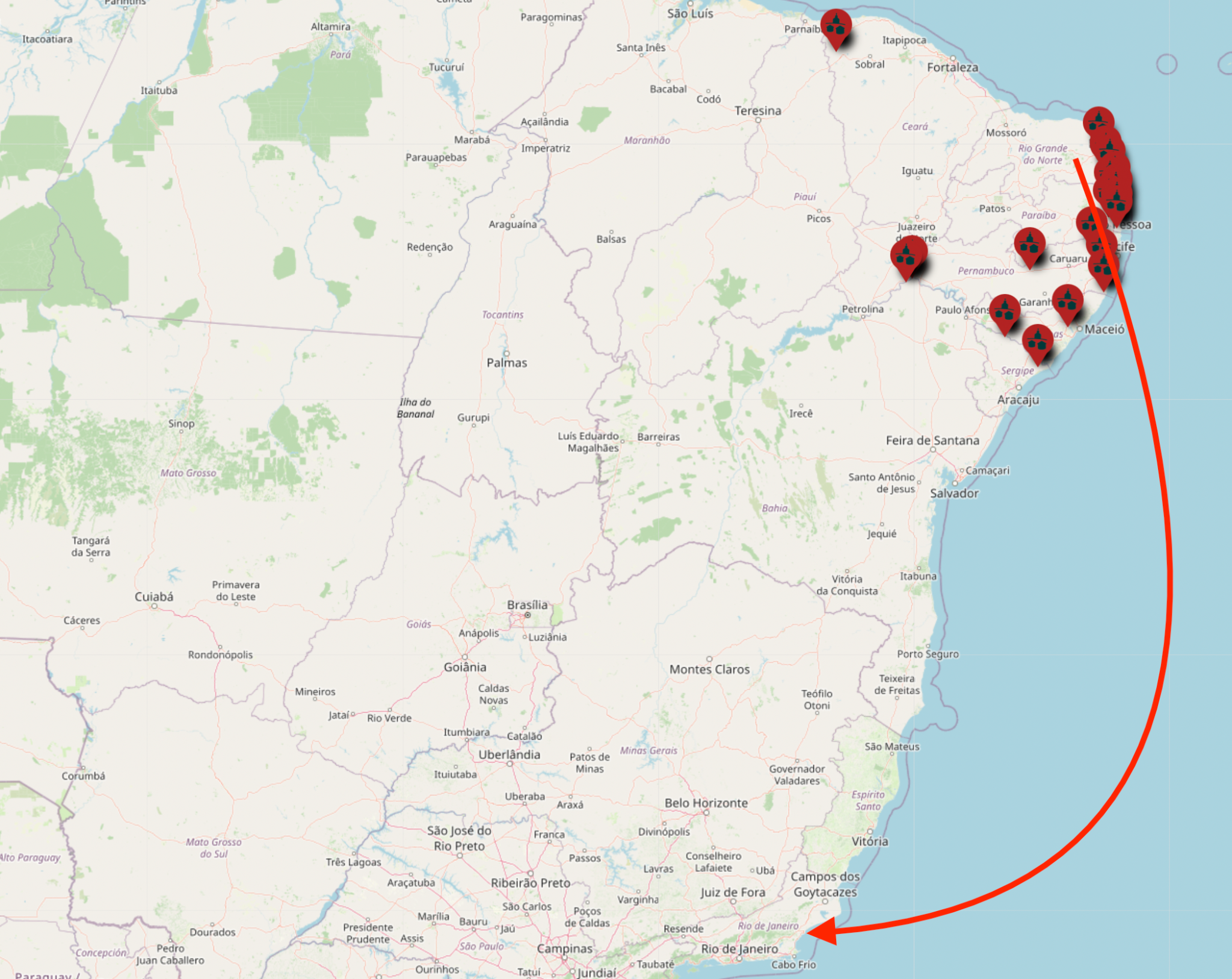

On July 11, 1693, Bishop Matias de Figueiredo e Melo sent a report to the Vatican describing the situation of the Diocese of Pernambuco, which included the villages and missions of the colonial Northeast under his jurisdiction. In the case of the order from the Junta das Missões de Pernambuco, the Indigenous people of the Janduí, Caboré and Capela ethnic groups were to be removed from the captaincy of Rio Grande do Norte and sent to the captaincy of Rio de Janeiro, as shown in Figure 6 below.

Figure 6: Map based on “Relatório da Diocese de Pernambuco” (1693). Original version available at: https://www.atlasindigena.org/post/1693-relatório-da-diocese-de-pernambuco.

Through this territorial dispossession, Indigenous people were possibly forced to work as captives, in the captaincy of Rio de Janeiro, and were politically and socially disconnected from their respective groups and territories in the captaincy of Rio Grande do Norte, approximately 2,000 kilometers away.

It is worth noting that the captaincy of Rio de Janeiro was known as a region of intense trade in captives, even in the colonial period. This trade was carried out mainly by sertanistas from São Paulo who were at the forefront of the fighting against the Indigenous people of the Northeast. An order issued by the governor of Rio de Janeiro, Duarte Teixeira Chaves, dated April 7, 1684, for example, ordered the people of this captaincy to return the Indigenous people taken from the Rio das Caravelas, in the captaincy of Porto Seguro, to the Paulistas who had sold them.4

Therefore, far from being a war of complete destruction and the extinction of Indigenous peoples, the so-called “War of the Barbarians”, functioned as a process of removing indigenous people as captives, since the conquerors intended to occupy their territories after the war. In this sense, within the colonial game, the specificities of local contexts do not allow us to generalize or say that Indigenous people were all “exterminated” (or killed) in the war.

Even the very understanding of “extermination” (which, in the context used by the Junta, differs from the notion of killing) reinforces an idea of territorial despoilment — a facet not generally observed. This process of forced removal would not necessarily imply death or prevent the possibility of resistance, escape, or territorialization in the new destination.

In addition, recent historiography has increasingly pointed to the negotiations and agency of Indigenous peoples in these wars, such as the signing of peace agreements or taking up military positions alongside the Portuguese themselves. In some cases, these were wars between Indigenous people of different ethnicities — and furthermore, not only wars, but also the displacement of prisoners, as in the painting by Jean-Baptiste Debret in Figure 1. The interpretation of “extermination” presented here therefore does not detract from the weight of the violence suffered by the Indigenous people. Instead it reinforces the need to more closely examine the complexity of the colonial period, especially from the point of view of Indigenous people themselves, whenever possible.

References

ATLAS do Pernambuco Indígena. Map based on “Relatório da Diocese de Pernambuco” (1693), 2023.

BANDO do Governador do Rio de Janeiro, Against the people who bought Indians. April 7, 1684. ANRJ, Codex 77, vol. 1.

BLUTEAU, Rafael. Dicionário da língua portuguesa composto pelo padre D. Rafael Bluteau, reformado, e acrescentado por Antonio de Moraes Silva natural do Rio de Janeiro. Lisboa: Officina de Simão Thaddeo Ferreira, 1789.

DEBRET, Jean-Baptiste. Índios soldados da província de Curitiba escoltando prisioneiros nativos, 1834, 21 x 32,5 cm, Coleção Brasiliana, Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo, available online in Atlas Histórico do Brasil.

FUNDAÇÃO Getúlio Vargas. Caminhos do Gado, Map of “The Northeast of Sugarcane and Cattle in the 17th century”. Available online in Atlas Histórico do Brasil, 2023.

Minutes of the Junta das Missões de Pernambuco. National Library of Lisbon, Pombalina Collection, Codex 115.

PUNTONI, Pedro. A Guerra dos Bárbaros: povos indígenas e a colonização do sertão do nordeste do Brasil, 1650-1720. São Paulo: Hucitec/Edusp, 2002.

Translated into English by the author. Cf. Puntoni, 2002, 45–46. ↩︎

Minutes of the Junta das Missões de Pernambuco, April 4, 1713. National Library of Lisbon, Pombalina Collection, Cod. 115, fl.210. ↩︎

BLUTEAU, Rafael. Dicionário da língua portuguesa composto pelo padre D. Rafael Bluteau, reformado, e acrescentado por Antonio de Moraes Silva natural do Rio de Janeiro. Lisboa: Na Officina de Simão Thaddeo Ferreira, 1789, p. 588. Available at: https://digital.bbm.usp.br/handle/bbm/5413. ↩︎

Bando do Governador do Rio de Janeiro, Against the people who bought Indians. April 7, 1684. ANRJ, codex 77, vol. 1, fl. 161v. ↩︎