Abstract

How do states use public health to manage their populations? This essay examines how the Chilean state used the growing science and politics of public health to manage Mapuche peoples, as they were being simultaneously dispossessed of their lands and of their lifeways—elements considered obstacles to their integration into the Chilean nation. This essay focuses on one of the earliest health policies specifically targeting Indigenous Peoples in Chile: the 1930 Regulation of Indigenous Cemeteries Decree. Through archival research, I trace how the Regulation of Indigenous Cemeteries led Mapuche communities, public health officials, and police to negotiate the certification and preservation of cemeteries within Mapuche reductions. This examination demonstrates how public health policies and institutions extended colonial land management strategies to the management of human populations. By repurposing land dispossession strategies to promote public health, state officials and health authorities drastically reshaped Mapuche lives and afterlives while framing it in terms of health and well-being.

By the late 19th century, industrialization and mass migration had raised “social questions” about worsening poverty, poor health, and increasing mortality rates among Chile’s poor and marginalized peoples.1 These issues spurred the growth of medicine and public health, reshaping the state’s role in promoting health and well-being.2 New public health laws and institutions emerged, culminating in the 1925 Constitution, which declared, “the duty of the State to watch over the public health and hygienic welfare of the country.”

Parallel to these developments, the Chilean military occupied Wallmapu, the Mapuche ancestral territory. Mapuche land was divided and enclosed into legally owned plots, altering Mapuche relationships with their territory.3 This process of land enclosure not only physically or spatially subdivided Mapuche peoples’ territory; it also legally redefined peoples’ connections to the land.4 This facilitated land dispossession, forced settlement, and urban migration. By 1929, the enclosure and settlement of land in the region of La Araucanía, Southern Chile was complete.

These changes devastated Wallmapu’s health and social fabric. Mapuche communities suffered epidemics of cholera (1867), typhus (1892), and smallpox (1904–1906, 1922).5 Starvation was widespread. Those who remained on the reductions had to adapt their ways of life and death in the face of expanding government and religious institutions. In 1930, these new public institutions converged with Mapuche efforts to refashion life on the reductions when the Ministry of Social Welfare passed Decree 1754, more commonly known as the Regulation of Indigenous Cemeteries.

This essay examines how the Chilean state used the growing science and politics of public health to manage Mapuche peoples, further dispossessing them of their lands and lifeways. I focus on one of the earliest health policies specifically aimed at Indigenous Peoples in Chile: the 1930 Regulation of Indigenous Cemeteries Decree. This regulation was legislated and overseen by the General Directorate of Health, the nation’s governing body responsible for public health and safety. It granted the General Directorate of Health legal oversight over the burial of Indigenous peoples, the certification of new cemeteries on Indigenous land, and the conservation of existing eltun or Mapuche burial grounds.

I explore how the Regulation of Indigenous Cemeteries (herein, the “Regulation”) led to negotiations between Mapuche communities, public health officials in the region of La Araucanía and the city of Santiago, and the police over cemetery certification and preservation within reductions. Scholars have noted that early public health experts adopted colonial strategies to address health concerns.6 I build on this work to show how public health policies and institutions extended colonial land management strategies to promote the health of human populations. Specifically, I focus on how land enclosure practices were used to create cemeteries as physically bounded sites under legal and public health oversight within Mapuche reductions.

There were likely tangible public health benefits to these approaches.7 However, state officials and health authorities achieved these benefits by repurposing colonial land enclosure strategies and prioritizing emerging notions of hygiene over Mapuche funerary rites that uphold the well-being of families and communities. By transforming cemeteries into sites of legal and public health oversight, officials reshaped Mapuche lives and afterlives within the context of health and well-being.

Through archival research, I present two cases where the physical location of the cemetery itself became a point of contention, leading to the General Directorate of Health’s eventual approval or denial of a Mapuche community’s cemetery.

“Anti-Regulation and dangerous”

Early 20th-century scientific advances in water quality, infection control, and epidemiology influenced public health concerns regarding burial practices and cemetery characteristics.8 To address these concerns, the Regulation of Indigenous Cemeteries established specifications for cemeteries, dictating topography, land area, soil conditions, land use, and methods of fencing and enclosure to curb the spread of infectious diseases to nearby water sources.9

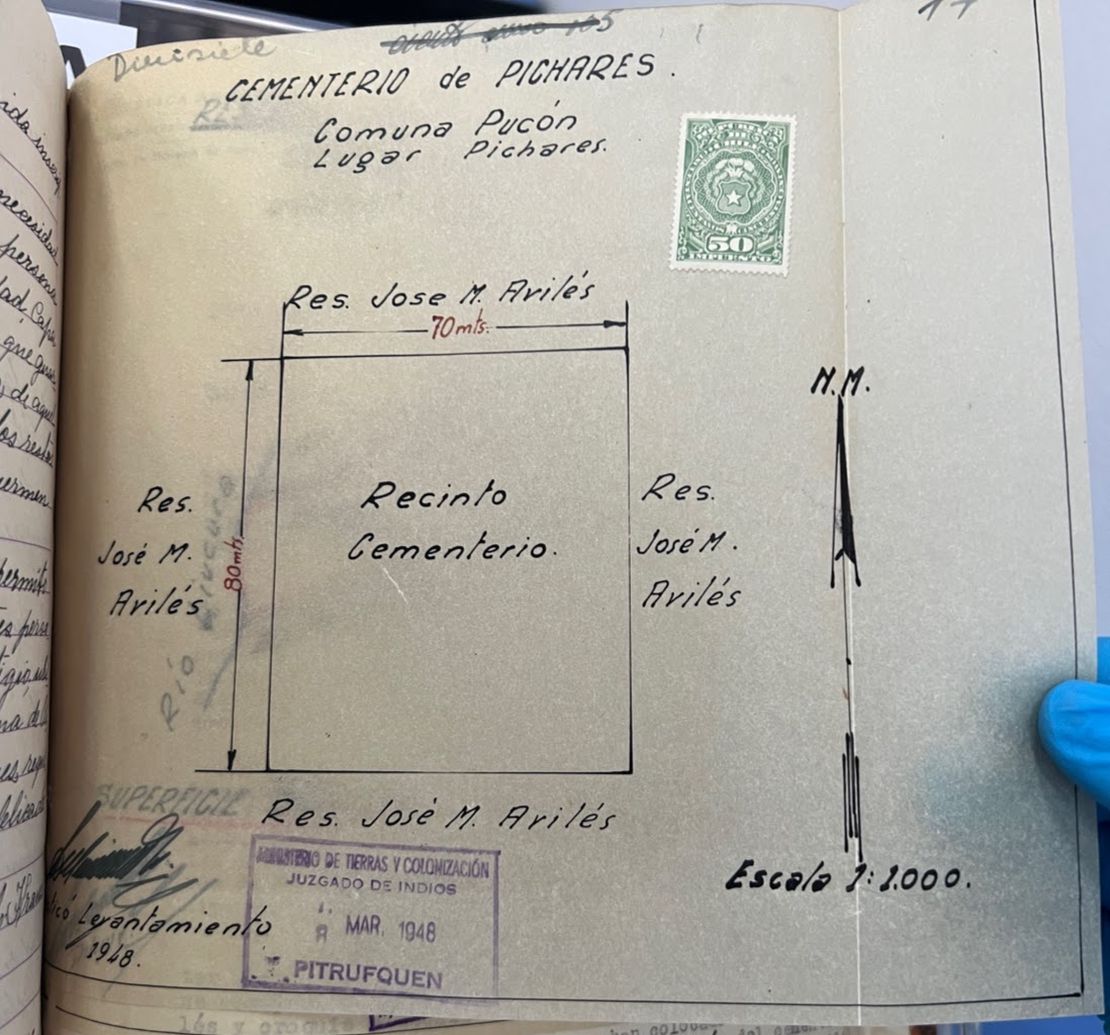

In La Araucanía, similar land survey and management techniques were used to enclose and legally define Mapuche territory.10 Article 2, for example, required Mapuche communities to designate and enclose at least 500 square meters of their already limited reduction land for cemeteries. Cemeteries had to have “a perfect enclosure made of a solid wall or continuous wood, resistant, 2 meters high and with a protective fence.” Article 3 specified that cemeteries could not be located within 25 meters of a dwelling, within 50 meters of a water source, be used for cultivating fruit trees or crops, or be used for any purposes other than burial. Public health authorities commissioned local police to verify compliance by writing reports and mapping cemetery sites (see fig. 1).

These overlapping requirements proved troublesome for the Folilco reduction, where a prospective cemetery site was built too close to a dwelling and a stream.11 The cemetery fence was also erected through a field that was being used to cultivate food crops. In a police report commissioned to verify the site characteristics, the prospective cemetery was deemed “anti-Regulation and dangerous because it does not meet the hygienic conditions,” thereby equating legal compliance with public health and safety. Consequently, the Director General denied Folilco certification of their cemetery.

“This is justice”

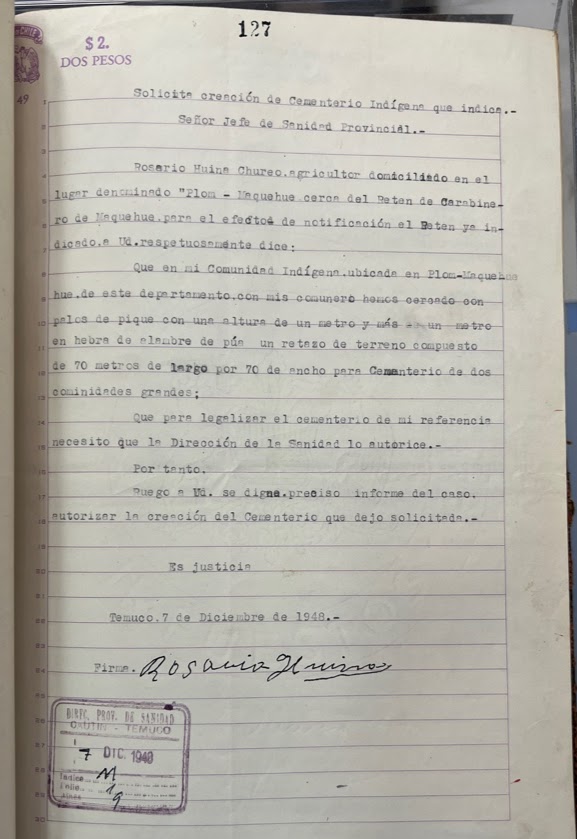

At times, the realities of life on the reductions made it impossible for some Mapuche communities to comply with the Regulation’s legal standards. In his 1948 letter to the General Directorate of Health, Rosario Huina Chureo of the Plom Maquehue reduction wrote, “with my community members, we have fenced with picket poles to a height of one meter and topped with one meter of barbed wire.”12

Reports from public health authorities and police noted that the Plom Maquehue fence did not meet the Regulation’s requirement for a solid, two-meter high “perfect enclosure.” The regional public health authority explained in his report to the General Directorate in Santiago that there was “an absolute lack of wood, which has already been presented in almost all Indigenous reductions, such that if they are required to comply with this requirement, they are not in a condition to buy wood.”13

This “absolute lack of wood” occurred in a region where vast native forests were being felled for timber, and decades later, forestry industries would own and cultivate almost three million acres of pine and eucalyptus plantations.14 Despite the lack of wood for a full enclosure, the regional public health authority requested that the General Directorate approve the cemetery, noting its “apt conditions,” the “widely justified needs of the inhabitants,” and that there was “no objection” from his office.

Despite the regional health authorities’ allowance, Mapuche people began to criticize the Regulation’s requirements as discriminatory and unjust given the material conditions of life on the reductions. In the same report, the regional public health authority noted that the center-right Mapuche politician, Venancio Coñuepán, “met with the undersigned—the regional Chief Sanitation Authority—expressing that this requirement is prejudicial for his constituents and that he would be pleased if the authorization were granted under these conditions, given that the fence is well closed anyway.”15

Rosario Huina Chureo made a similar, albeit less overt, statement in his request for the Directorate General to approve the partially enclosed cemetery. He concluded his letter with two final words typed on a line of their own: “Es justicia.” This is justice. (See fig. 2).16

Huina Chureo’s letter and the regional public health official’s report were sent to the Directorate General, who ultimately approved the cemetery in Plom Maquehue.17

Figure 2. Rosario Huina Chureo’s 1948 letter to the Directorate General of Health (full page & close-up). Huina Chureo signs off the letter, “This is justice.”

Holes in the Enclosure

The archive of requests to certify cemeteries under the Regulation of Indigenous Cemeteries reveals the expanding public health and legal framework in Southern Chile and the compliance it demanded of Mapuche people. In their efforts to turn Mapuche people into “hygienic” and “civilized” subjects, the General Directorate of Health enforced strict requirements which were often difficult or impossible to meet. State health authorities employed colonial strategies to control Indigenous land, using the Regulation to enforce their version of public health and safety. This process turned Mapuche land and lifeways into sites of public health concern and legal action, reshaping their lives and afterlives.

However, Mapuche people’s consent to be governed coexisted with their efforts to preserve Mapuche spirituality, ceremonies, life, and afterlife. These struggles continue today. Eltun, or Mapuche burial grounds, are ancestral sites that communities seek to recover, recognize, and defend against policies, religious ideologies, and development that threaten to erase these spiritually and culturally significant sites. Elsewhere, I write about Mapuche-run intercultural clinics that offer both Mapuche medicine and Western biomedicine, creating new healthcare models that connect health and well-being to the territory. The complex negotiations between Chilean state institutions and Mapuche communities documented in the archive continue to have resounding effects in the present.

Archives

Fondo Dirección General de Sanidad, Archivo Nacional de la Administración, Santiago, Chile

References

Anderson, Warwick. Colonial Pathologies: American Tropical Medicine, Race, and Hygiene in the Philippines. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006.

Carter, Eric D. “Politics: Social Medicine and Health Reform in Chile.” In In Pursuit of Health Equity: A History of Latin American Social Medicine, 68–93. University of North Carolina Press, 2023. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5149/9781469674476_carter.8.

Correa Cabrera, Martín. “La historia del despojo.” In El origen de la propiedad particular en el territorio mapuche, 7–35. Santiago: Pehuén Editores, 2021.

Cuyul, Andrés. “Las pandemias y el pueblo mapuche.” Comunidad de Historia Mapuche (blog), May 31, 2020. https://www.comunidadhistoriamapuche.cl/las-pandemias-y-el-pueblo-mapuche/.

Di Giminiani, Piergiorgio. Sentient Lands: Indigeneity, Property, and Political Imagination in Neoliberal Chile. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2018.

Downs, Jim. Maladies of Empire: How Colonialism, Slavery, and War Transformed Medicine. Cambridge, MA; London, England: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2021.

“Folilco Reduction,” n.d. Dirección General de Sanidad, Vol. 444, N.100. Archivo Nacional de la Administración, Santiago, Chile. Accessed January 10, 2024.

Huina Chureo, Rosario. “To Señor Jefe de Sanidad Provincial,” December 7, 1948. Dirección General de Sanidad, Vol. 785, N.737. Archivo Nacional de la Administración, Santiago, Chile.

Illanes, María Angélica. “En el nombre del pueblo, del estado y de la ciencia, (…)”: historia social de la salud pública, Chile, 1880–1973 : (hacia una historia social del Siglo XX). Colectivo de Atención Primaria, 1993.

Irarrázaval Gomien, Andrés. “Hacia un nuevo consenso en la regulación de los cementerios: La evolución de las normas civiles y canónicas a lo largo del siglo XX.” Revista Chilena de Derecho 45, no. 1 (2018): 33–56.

Juzgado de Indios. “Cementerio de Pichares.” 1:1000. Pichares, Pucón: Ministerio de Tierras y Colonización, March 8, 1948. Dirección General de Sanidad, Vol. 785, N.766. Archivo Nacional de la Administración, Santiago, Chile.

Klubock, Thomas Miller. La Frontera: Forests and Ecological Conflict in Chile’s Frontier Territory. Radical Perspectives: A Radical History Review Book Series. Durham ; London: Duke University Press, 2014.

Lo Chávez, D. “Morir en el antiguo Iquique: Cementerios, salud pública y sectores populares durante la epidemia de peste bubónica de 1903.” Revista Nuestro Norte: Revista del Museo Regional de Iquique 1 (2015): 13–21.

Luco, Augusto Orrego. La cuestión social. Santiago: Imprenta Barcelona, 1889.

Muñoz Navarro, Augstín. “To Servicio Nacional de Salubridad.” January 13, 1949. Dirección General de Sanidad, Vol. 785, N.737. Archivo Nacional de la Administración, Santiago Chile.

Nahuelpán, Héctor, Edgars Martínez, Alvaro Hofflinger, and Pablo Millalén. “In Wallmapu, Colonialism and Capitalism Realign: As Mapuche Land Reclamations Threaten Corporate Profits, the Chilean State and Forestry Industry Double Down on Repression.” NACLA Report on the Americas 53, no. 3 (2021): 296–303.

Neckel, Alcindo, Carlos Costa, Débora Nunes Mario, Clarice Elvira Saggin Sabadin, and Eliane Thaines Bodah. “Environmental Damage and Public Health Threat Caused by Cemeteries: A Proposal of Ideal Cemeteries for the Growing Urban Sprawl.” Urbe. Revista Brasileira de Gestão Urbana 9 (February 13, 2017): 216–30. https://doi.org/10.1590/2175-3369.009.002.AO05.

Nichols, Robert. Theft Is Property!: Dispossession and Critical Theory. Duke University Press, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1215/9781478090250.

Rioja, Romina Green. “Land and the Language of Race: State Colonization and the Privatization of Indigenous Lands in Araucanía, Chile (1871–1916).” The Americas 80, no. 1 (January 2023): 69–99. https://doi.org/10.1017/tam.2021.143.

Rogaski, Ruth. Hygienic Modernity - Meanings of Health and Disease in Treaty-Port China. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014.

Scott, James C. Seeing like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. Yale University Press, 2008.

Żychowski, Józef, and Tomasz Bryndal. “Impact of Cemeteries on Groundwater Contamination by Bacteria and Viruses – a Review.” Journal of Water and Health 13, no. 2 (September 10, 2014): 285–301. https://doi.org/10.2166/wh.2014.119.

Augusto Orrego Luco, La cuestión social (Santiago: Imprenta Barcelona, 1889). ↩︎

María Angélica Illanes, “En el nombre del pueblo, del estado y de la ciencia, (…)”: Historia social de la salud pública, Chile, 1880–1973: (Hacia una historia social del siglo XX) (Colectivo de Atención Primaria, 1993); Eric D. Carter, “Politics: Social Medicine and Health Reform in Chile,” in In Pursuit of Health Equity: A History of Latin American Social Medicine (University of North Carolina Press, 2023), 68–93, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5149/9781469674476_carter.8. ↩︎

Martín Correa Cabrera, “La historia del despojo,” El origen de la propiedad particular en el territorio mapuche (Santiago: Pehuén Editores, 2021); Robert Nichols, Theft Is Property!: Dispossession and Critical Theory (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2020), https://doi.org/10.1215/9781478090250; Romina Green Rioja, “Land and the Language of Race: State Colonization and the Privatization of Indigenous Lands in Araucanía, Chile (1871–1916),” The Americas 80, no. 1 (January 2023): 69–99, https://doi.org/10.1017/tam.2021.143. ↩︎

Piergiorgio Di Giminiani, Sentient Lands: Indigeneity, Property, and Political Imagination in Neoliberal Chile (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2018). ↩︎

Andrés Cuyul, “Las pandemias y el pueblo mapuche,” Comunidad de Historia Mapuche (blog), May 31, 2020, https://www.comunidadhistoriamapuche.cl/las-pandemias-y-el-pueblo-mapuche/. ↩︎

Warwick Anderson, Colonial Pathologies: American Tropical Medicine, Race, and Hygiene in the Philippines (Durham, NC: Duke Univ. Press, 2006); Jim Downs, Maladies of Empire: How Colonialism, Slavery, and War Transformed Medicine (Cambridge, Massachusetts; London, England: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2021); Ruth Rogaski, Hygienic Modernity: Meanings of Health and Disease in Treaty-Port China (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014). ↩︎

Alcindo Neckel et al., “Environmental Damage and Public Health Threat Caused by Cemeteries: A Proposal of Ideal Cemeteries for the Growing Urban Sprawl,” Urbe. Revista Brasileira de Gestão Urbana 9 (February 13, 2017): 216–30, https://doi.org/10.1590/2175-3369.009.002.AO05; Józef Żychowski and Tomasz Bryndal, “Impact of Cemeteries on Groundwater Contamination by Bacteria and Viruses – A Review,” Journal of Water and Health 13, no. 2 (September 10, 2014): 285–301, https://doi.org/10.2166/wh.2014.119. ↩︎

Andrés Irarrázaval Gomien, “Hacia un nuevo consenso en la regulación de los cementerios: La evolución de las normas civiles y canónicas a lo largo del siglo XX,” Revista Chilena de Derecho 45, no. 1 (2018): 33–56; D. Lo Chávez, “Morir en el antiguo Iquique: Cementerios, salud pública y sectores populares durante la epidemia de peste bubónica de 1903,” Revista Nuestro Norte: Revista Del Museo Regional de Iquique 1 (2015): 13–21. ↩︎

Neckel et al., “Environmental Damage and Public Health Threat Caused by Cemeteries”; Żychowski and Bryndal, “Impact of Cemeteries on Groundwater Contamination by Bacteria and Viruses – A Review.” ↩︎

Rioja, “Land and the Language of Race”; James C. Scott, Seeing like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008). ↩︎

“Folilco Reduction,” n.d., Dirección General de Sanidad, Vol. 444, N.100, Archivo Nacional de la Administración (Santiago, Chile), accessed January 10, 2024. ↩︎

Rosario Huina Chureo, “To Señor Jefe de Sanidad Provincial,” December 7, 1948, Dirección General de Sanidad, Vol. 785, N.737, Archivo Nacional de la Administración, Santiago, Chile. ↩︎

Augstín Muñoz Navarro, “To Servicio Nacional de Salubridad,” January 13, 1949, Dirección General de Sanidad, Vol. 785, N.737, Archivo Nacional de la Administración, Santiago, Chile. ↩︎

Thomas Miller Klubock, La Frontera: Forests and Ecological Conflict in Chile’s Frontier Territory, Radical Perspectives: A Radical History Review Book Series (Durham, NC ; London, England: Duke University Press, 2014); Héctor Nahuelpán et al., “In Wallmapu, Colonialism and Capitalism Realign: As Mapuche Land Reclamations Threaten Corporate Profits, the Chilean State and Forestry Industry Double down on Repression,” NACLA Report on the Americas 53, no. 3 (2021): 296–303. ↩︎

Muñoz Navarro, “To Servicio Nacional de Salubridad,” January 13, 1949. ↩︎

Huina Chureo, “To Señor Jefe de Sanidad Provincial,” December 7, 1948. ↩︎

Muñoz Navarro, “To Servicio Nacional de Salubridad,” January 13, 1949. ↩︎