Abstract

For Mapuche Indigenous peoples in the territory of Boroa, in Southern Chile, health and health actions are part of ongoing legacies of territorial and cultural dispossession, as well as expressions of Indigenous forms of spirituality, more-than-human relations, and political self-determination. To consider how these ongoing experiences unfold via changing states of health and illness, we–a multidisciplinary group of community-based clinicians and an academic anthropologist–have devised a framework we call the territorial processes of health. The territorial processes of health approach health and illness as embodied (dis)equilibria in the dynamic ecology of human and more-than-human relations in a given place. By foregrounding health as a lens to understand how people live relationally in and with a place, we offer the “territorial processes of health” as a framework that we hope can travel beyond Boroa to inspire people to work towards forms of health and healing in concert with the territories around them.

On the dirt roads that crisscross rural Southern Chile, 18-wheel cargo trucks carrying lumber and grain speed down the straight stretches, while sedans and trucks spin their tires trying to turn off one dirt road onto another. The dust and other particulates kicked up by the traffic find their way into the open windows of nearby homes and into people’s respiratory tracts. For people living with lung conditions like asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), chronic exposure to air-borne particulates like dust can worsen and exacerbate these chronic conditions.1 Disease exacerbations can require specialized medications or even hospitalization—both of which are difficult to access for people living in rural communities, where few own cars, and hospitals are many kilometers away.

Through a series of community conversations in the Mapuche territory of Boroa, community leaders and local healthcare providers began to investigate the conditions that triggered peoples’ underlying medical conditions. Recognizing the role that Boroa’s many unpaved roads played, they set out to lobby the local government to pave these roads. The newly paved roads reduced dust exposure in nearby homes to help mitigate asthma and COPD exacerbations. Yet, these newly paved roads also reshaped the ways people lived and moved through their territory, which influenced peoples’ health in complex, sometimes unexpected ways.

This example seeks to illustrate how actions in our environment shape our health, and, in turn, how actions taken to influence health shape our environments. In other words, health is an inseparable part of this social environment.

Prominent medical and public health frameworks like the “risk factors” and “social determinants of health” have been critical for building a more socially conscious approach to health and health care. However, these frameworks rely on terms like “factors” or “determinants” to describe directional cause and effect relationships that inadvertently separate human health from the social environment.2

These models cannot adequately describe the intercultural conceptions of health and health action practiced in Mapuche Indigenous communities in the ancestral Mapuche territory of Boroa in Southern Chile. The health care providers who work at the Intercultural Health Center Boroa Filulawen (and often live in the territory of Boroa) have clearly traced the interdependencies of their patients’ health and what happens in the territory. They have sought to approach peoples’ health and health actions as part of ongoing legacies of territorial and cultural dispossession, as well as expressions of Indigenous forms of Mapuche spirituality, in connection with the socio-natural environment, and the political self-determination for the Boroa communities and the Mapuche People.

How do these broader processes play out through the experiences of health and illness? To visibilize how these processes unfold, we have devised a framework known as “territorial processes of health.” This framework conceptualizes a person’s health and illness as (dis)equilibrium in one’s body, but also in one’s familial, social, and spiritual relations—a conceptualization rooted in the Mapuche conceptions of küme mongen (buen vivir or living well) and kutran (illness).3 This (dis)equilibrium is influenced by the dynamic network of human and more-than-human relationships that have an impact on a person, and on which that person impacts, too. Finally, we use this notion of embodied (dis)equilibrium to extend discussions within Latin America´s collective health and social medicine that describe health, illness, and treatment as social and historical processes.4

This essay begins by introducing the Intercultural Clinic Boroa Filulawen, the clinic where the territorial processes of health were first conceptualized. Next, we summarize the concept´s evolution. Additionally, we draw on Emily Yates-Doerr’s framework for parsing out the “social determinants of health” to break down the “territorial processes of health” into its essential parts.5 Finally, we bring these parts together by revisiting the opening example of road paving to examine how an understanding of territorial processes may promote health and prevent disease.

Boroa Filulawen

The Intercultural Health Center Boroa Filulawen (or Filulawen) (Fig. 1) arose from a community-led effort to improve the health and well-being of Mapuche communities in the territory of Forrowe/Boroa. In the late 1990’s, community leaders began to hold nutramkawün (conversations) to diagnose critical needs in their communities. These needs included rural drinking water, road improvement, environmental protection of native forests and therapeutic flora, economic opportunities to sell agricultural produce, land reclamation, and access to dignified health care.

To address this final point, a group of young Mapuche leaders organized the Boroa Filulawen Intercultural Health Committee. The Committee proposed a “New Model for Rural Health,” which centered around a self-managed community health center run by Indigenous local people. This New Model, which remains the basis of Filulawen’s approach almost twenty years later, “proposed an analysis of the historical and social [self-]determination of the Mapuche people and sought to improve and innovate the traditional rural health centers in Chile."6

Figure 1. The Boroa Filulawen Intercultural Health Center, pictured here, is led by Mapuche community leaders, including legal representative Don Antonio Huircan (co-founder), Director Don Rolando Curiqueo, and ragiñelwe (intercultural health facilitator) Don Abelino Pichicona (co-founder); and the longko (ancestral political leaders), Luis Silverio Colimil Lizama, Mario Bonito Pichicón, y Pedro Rayman Licanqueo. Day-to-day operations are overseen by the clinic executive team led by Carlos Benito, Dr. Fabiola Silva, and Marcelo del Río, and made possible by many committed staff. This work would not have been possible without their leadership and dedication; chaltu may kom pu che (thank you everyone). Photo credit: Boroa Filulawen.

The Boroa Filulawen Intercultural Health Center started operations in December 2003. The clinic offers biomedical primary care as well as Mapuche medical and spiritual care, including appointments with machi (medical-spiritual authority), lawentuchefe (expert in herbal medicine), and community prayers and ceremonies. In addition, Filulawen has served as a focal point for numerous territorial efforts and activities, including efforts to recover land, strengthen the social fabric, support rural schools, and revitalize Mapuche ceremonies and gastronomy.

Through conversations held among co-authors —an academic anthropologist and medical student (RB) and Filulawen´s clinical leadership team charged with guiding an intercultural clinic’s everyday operations (CBQ, FS, MdRS, DCC)—, we spotted the need for a new language to describe the health approach adopted in Boroa. We turned to collaborative and ethnographic research, as well Mapuche understandings of social and territorial philosophies,7 along with Latin American paradigms of critical epidemiology and collective health. In the next section, we present a brief synthesis of this work by explaining each of the three primary components of the “territorial processes of health framework.”

The Territorial Processes of Health in Three Parts

“Territorial”

Territorial, in our conception, is grounded in Mapuche Indigenous understanding of territory, in contrast with the colonial-capitalist framework of territory perceived as inanimate property.8 Frequently, the term mapu —in Mapuzugun, the Mapuche language— is translated into “land,” and mapu-che or Mapuche into “people of the land.” However, these translations simplify the multiple relational and spatial dimensions of mapu, which has a foundational connection to mongen (life), writes Miguel Melin, a Mapuche intercultural professor from Boroa.9 Our use of the word “territory” or “territorial” attempts to highlight this spatial relational dimension of mapu that makes it fundamental to the mongen (life) of not only humans, but also other beings that inhabit the territory. However, translations are imperfect and incomplete to encompass worldviews and histories. So, we use “territory” not as an expression of Mapuche worldview and philosophy per se, but as a conceptual tool so that the Mapuche worldview can shape notions of health in more complex, relational, and “situated”10 ways than the current uses of “social” or “environmental” in Western medicine and public health.

Territory, as defined and operationalized herein, comes from the ancestral territory of Forrowe, or Boroa as it is called today. It is grounded in the collective experiences of clinic leadership and staff who have sustained a Mapuche-led clinic in spite of persistent disinvestment and dispossession efforts. While the concept of territorial processes of health may be applicable or generative to other contexts, the territorial processes understood and intervened upon within Filulawen’s practice are inseparable from the historical time and place in which they were developed. Not all territories are the same; each has its own history, character, and “regulatory system”, or az mapu.11 Hence, not all processes are the same, and health care and health needs will differ in different locations. The services delivered by Filulawen covers the territory of Boroa and its 81 distinct Mapuche communities, where 90% of the population is rural and 90% is Mapuche.12

“Process”

Our understandings of health and territory as complex categories required a term that could account for the multiple, dynamic relationships that exist and shape health and territory. We decided to use “process,” a term borrowed from work in Latin American social medicine, to approach those relations.13 Process —unlike “determinant”— acknowledges the multidirectional interplay between the territory (in its multiple human and more-than-human components) and health. It also accounts for the interdependency of territory and health, recognizing that health is inseparable from the territory. Moreover, the process —unlike “factor”— denotes the dynamic and historical dimensions of how health unfolds in the territory. Finally, the process allows for an understanding of the relation between health and territory that is shaped by history, but that can be influenced through actions in the present.

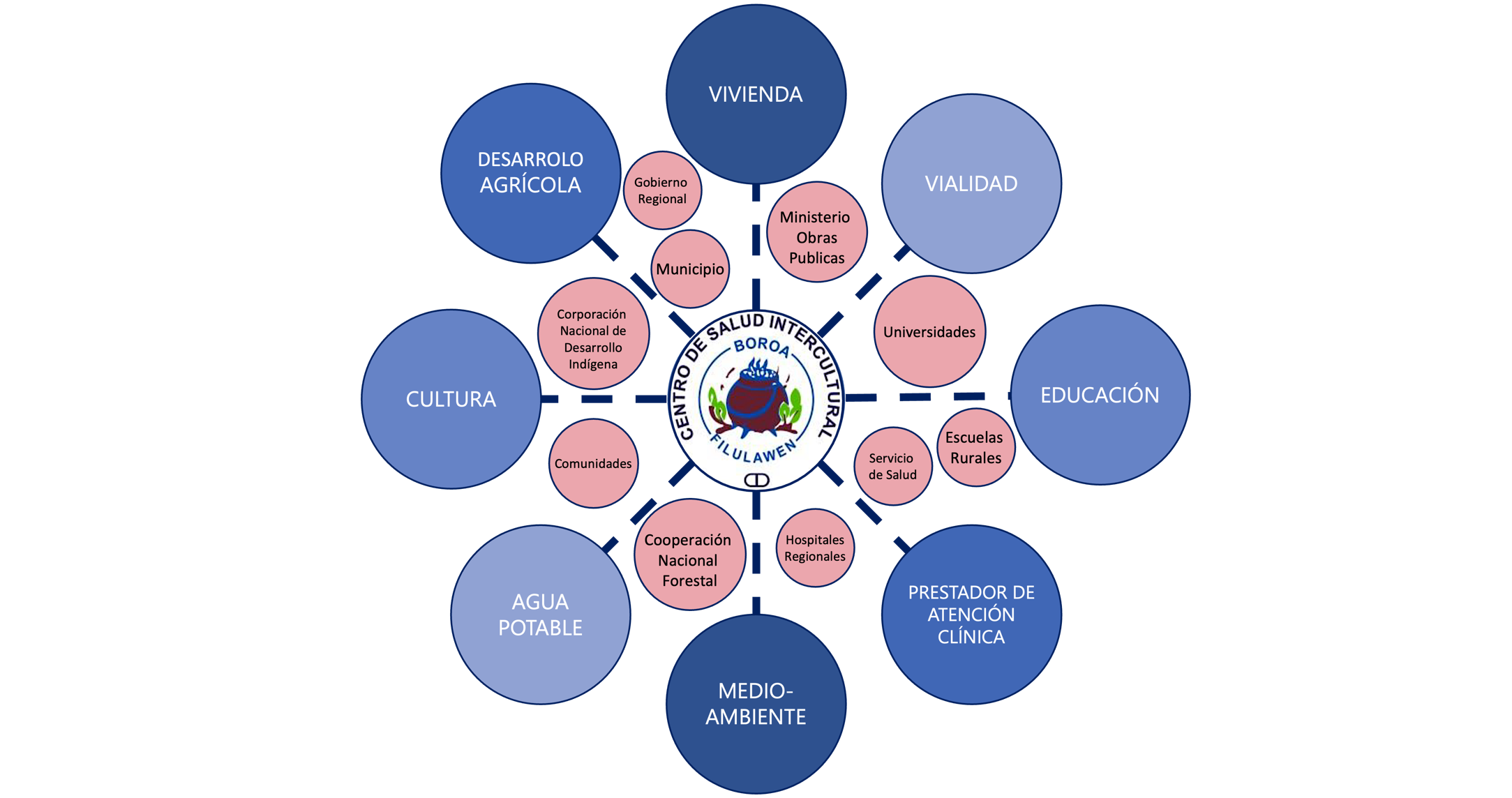

To promote health in the territory, efficient clinical care is not sufficient; other forms of care are also necessary. Therefore, the health center acts as a convening agent for numerous public entities, community-led and territory-based organizations, and community members to enact an “inter-sectorial” practice to enhance individual, family, community, territorial, and environmental well-being (Figure 2). This work, often led and coordinated by leaders in the center and in the community, has been developed over two decades of services targeting the health needs of the population, and long-standing dedication and engagement in Boroa. This intersectoral work remains a cornerstone of how Boroa Filulawen is intervening in historical processes to promote health in the territory.

Figure 2. Diagram that identifies the various action areas and key stakeholders with which the CSI Boroa Filulawen works to address territorial processes of health

“Health”

Health, in this brief description based on a Mapuche worldview, can be thought of as a balance between küme mongen (well-being) and kutran (ill health). Health encompasses all the dimensions that form part of one’s being as “che” or person, including one’s physical, psychological, emotional, social and spiritual dimensions. These exist in a dynamic equilibrium within an individual, family, community, and territory. Changes or disruptions to any part of this system can manifest in our bodies —bodies that live in specific times, places, and conditions. In other words, health and illness are ways of acknowledging shifts in a world inhabited by humans and more-than-humans, e.g. animals, plants, spirits, ancestors, rivers, oceans, and volcanos, who have their specific newen (energies) y ngen (spiritual owner or guardian).

Health —and thus, healthcare— in Boroa is fundamentally plural and intercultural, shaped by the two primary healthcare systems —Mapuche and Western biomedicine— and an array of community-based and other medical practices. Here, “intercultural” not only implies the co-existence or complementarity of medicines, but also allows Mapuche worldviews to influence how health is approached in greater complexity, even shaping how biomedicine itself is practiced in Boroa Filulawen. This approach to health is based on a Mapuche worldview that requires more than Western medical care at a clinic center. It focuses on solving health problems through examining the different social processes of health that affect people.

Applying the Territorial Processes of Health Framework

In our attempt to bring the territorial processes of health framework together, we wish to go back to the example of paving dirt roads. In a classic model of health determinants, paving the roads would address an environmental factor —i.e., dust from dirt roads— underlying a health problem —i.e., children’s asthma attacks. By mitigating asthma attacks, road pavement would be an effective intervention, whereby success is determined by their impact on people’s respiratory condition.

However, if we pay attention to territorial processes, we may see that paving the roads has created a host of other effects for Boroa´s families, communities, and environments. For instance, paved roads have made it easier and faster for families to transport their agricultural products to the city to sell, increasing economic opportunities for rural farmers. This development has also increased access to urban life in nearby towns, which stirs changes associated with dietary habits, job and educational opportunities, and social fabric. Paved roads have also boosted the speed of vehicles passing through the territory, posing new dangers for pedestrians, livestock, and other animals moving along these same routes.

Considering the health dimensions of these territorial processes allows us to understand how a health center supporting an intervention aimed at improving the living conditions of a community, can change the course of everyday experiences that include, but do not prioritize health. As compared to a focus on social “factors” or “determinants” that give priority to health, a territorial approach to health allows Filulawen to address both people-based health through clinical services, while seeking to promote a more overarching vision for the health and well-being of the territory of Boroa.

The framework for health as a territorial process includes but does not privilege clinical care. Instead, it seeks to acknowledge, value, and strengthen the local resources, collectives, practices, and know-how used to face health problems and strengthen küme mongen/buen vivir/well-being.14 By placing health at the forefront as a lens to understand how people live and relate to their environment, we offer the “territorial processes of health” as a framework that we hope may travel beyond Boroa to inspire people to work towards forms of health and healing in concert with the territories around them. Chaltu may. Thank you very much.

Bibliography

Breilh, Jaime. Critical Epidemiology and the People’s Health. Oxford University Press, 2021.

Caniullan Coliñir, V, and F Mellico Avendaño. “Mapuche Lawentuwün. Formas de Medicina Mapuche.” R. Becerra, & G. Llanquinao, Mapun Kimün. Relaciones Mapunche Entre Persona, Tiempo y Espacio (Págs. 41-79). Santiago de Chile: Ocho Libros Editores, 2017.

Caniullan, Víctor. “El mundo mapuche y su medicina,” August 28, 2011. https://repositoriodigital.uct.cl/handle/10925/460.

Comité de Salud Intercultural Boroa Filulawen. “Modelo de Salud: Centro de Salud Intercultural y Comunitario Boroa Filulawen,” March 2018.

Cuyul, Andres. “Bawehtuwün Zugu Mapuche Rakizuam Mew: Salud Colectiva y Pensamiento Mapuche,” n.d.

———. “Epidemiología Sociocultural: Los Procesos Protectores de La Salud y El Conocimiento En Salud de Las Comunidades.” Accessed January 3, 2024. https://www.academia.edu/4341208/Epidemiolog%C3%ADa_Sociocultural_Los_procesos_protectores_de_la_salud_y_el_conocimiento_en_salud_de_las_comunidades.

———. “Prácticas Culturales Familiares y Colectivas Que Protegen La Salud En Comunidades Mapuche En Chile y Argentina y Su Consideración Por Parte de Los Equipos de Salud Oficiales.” Maestría en salud pública, Universidad de Buenos Aires, 2008.

Di Giminiani, Piergiorgio. Sentient Lands: Indigeneity, Property, and Political Imagination in Neoliberal Chile. University of Arizona Press, 2018.

Guarnieri, Michael, and John R. Balmes. “Outdoor Air Pollution and Asthma.” Lancet (London, England) 383, no. 9928 (May 3, 2014): 1581–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60617-6.

Haraway, Donna. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” Feminist Studies 14, no. 3 (1988): 575–99.

Harvey, Michael, Carlos Piñones-Rivera, and Seth M. Holmes. “Thinking with and against the Social Determinants of Health: The Latin American Social Medicine (Collective Health) Critique from Jaime Breilh.” International Journal of Health Services 52, no. 4 (2022): 433–41.

Krieger, Nancy. Epidemiology and the People’s Health: Theory and Context, Second Edition. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780197695555.001.0001.

Laurell, Asa Cristina. “La Salud-Enfermedad Como Proceso Social.” Revista Latinoamericana de Salud 2, no. 1 (1982): 7–25.

Melin Pehuen, Miguel, Patricio Coliqueo Collipal, Elsy Curihuinca Neira, and Manuela Royo Letelier. “Azmapu. Una Aproximación al Sistema Normativo Mapuche Desde El Rakizuam y El Derecho Propio,” 2016. https://bibliotecadigital.indh.cl/handle/123456789/984.

Menéndez, Eduardo L. “El Modelo Médico y La Salud de Los Trabajadores.” Salud Colectiva 1 (2005): 9–32.

Nichols, Robert. Theft Is Property!: Dispossession and Critical Theory. Duke University Press, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1215/9781478090250.

Pichinao Huenchuleo, Jimena, Fresia Mellico Avendaño, and Ernesto Huenchulaf Cayuqueo. Mapunche Gijañmawün Gülu Ka Puwel Mapu. La Forma Mapunche de Pensar y Practicar La Socialidad Religiosa En Gülu y En Puwel Mapu. 1st ed. Ediciones UC Temuco, 2023.

Quiñones, Pablo Mansilla, Miguel Melín Pehuén, and Manuela Royo Letelier. Cartografía Cultural Del Wallmapu: Elementos Para Descolonizar El Mapa En Territorio Mapuche. LOM ediciones, 2020. https://books.google.com/books?hl=es&lr=&id=n2YLEAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PT2&dq=cartografia+mapuche+&ots=J4srvY6P3i&sig=tKwrazCZPcCz38d4UXCMjnUAghk.

Yang, Ian A., Christine R. Jenkins, and Sundeep S. Salvi. “Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in Never-Smokers: Risk Factors, Pathogenesis, and Implications for Prevention and Treatment.” The Lancet. Respiratory Medicine 10, no. 5 (May 2022): 497–511. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00506-3.

Yates-Doerr, Emily. “Reworking the Social Determinants of Health: Responding to Material-Semiotic Indeterminacy in Public Health Interventions.” Medical Anthropology Quarterly 34, no. 3 (September 2020): 378–97. https://doi.org/10.1111/maq.12586.

Guarnieri and Balmes, “Outdoor Air Pollution and Asthma”; Yang, Jenkins, and Salvi, “Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in Never-Smokers.” ↩︎

Breilh, Critical Epidemiology and the People’s Health; Krieger, Epidemiology and the People’s Health; Harvey, Piñones-Rivera, and Holmes, “Thinking with and against the Social Determinants of Health.” ↩︎

For a written discussion of Mapuche medicine written by Victor Caniullan, a machi or Mapuche medical-spiritual authority, see: Caniullan, “El mundo mapuche y su medicina”; Caniullan Coliñir and Mellico Avendaño, “Mapuche Lawentuwün. Formas de Medicina Mapuche.” ↩︎

Breilh, Critical Epidemiology and the People’s Health; Cuyul, “Prácticas Culturales Familiares y Colectivas Que Protegen La Salud En Comunidades Mapuche En Chile y Argentina y Su Consideración Por Parte de Los Equipos de Salud Oficiales”; Cuyul, “Epidemiología Sociocultural”; Laurell, “La Salud-Enfermedad Como Proceso Social”; Menéndez, “El Modelo Médico y La Salud de Los Trabajadores.” ↩︎

Yates-Doerr, “Reworking the Social Determinants of Health: Responding to Material-Semiotic Indeterminacy in Public Health Interventions.” ↩︎

Comité de Salud Intercultural Boroa Filulawen, “Modelo de Salud: Centro de Salud Intercultural y Comunitario Boroa Filulawen,” 34. ↩︎

Pichinao Huenchuleo, Mellico Avendaño, and Huenchulaf Cayuqueo, Mapunche Gijañmawün Gülu Ka Puwel Mapu. La Forma Mapunche de Pensar y Practicar La Socialidad Religiosa En Gülu y En Puwel Mapu; Quiñones, Pehuén, and Letelier, Cartografía Cultural Del Wallmapu. ↩︎

Di Giminiani, Sentient Lands; Nichols, Theft Is Property! ↩︎

Melin Pehuen et al., “Azmapu. Una Aproximación al Sistema Normativo Mapuche Desde El Rakizuam y El Derecho Propio.” ↩︎

Haraway, “Situated Knowledges.” ↩︎

Melin Pehuen et al., “Azmapu. Una Aproximación al Sistema Normativo Mapuche Desde El Rakizuam y El Derecho Propio.” ↩︎

Comité de Salud Intercultural Boroa Filulawen, “Modelo de Salud: Centro de Salud Intercultural y Comunitario Boroa Filulawen.” ↩︎

Laurell, “La Salud-Enfermedad Como Proceso Social”; Menéndez, “El Modelo Médico y La Salud de Los Trabajadores.” ↩︎

Cuyul, “Epidemiología Sociocultural”; Cuyul, “Bawehtuwün Zugu Mapuche Rakizuam Mew: Salud Colectiva y Pensamiento Mapuche.” ↩︎