Abstract

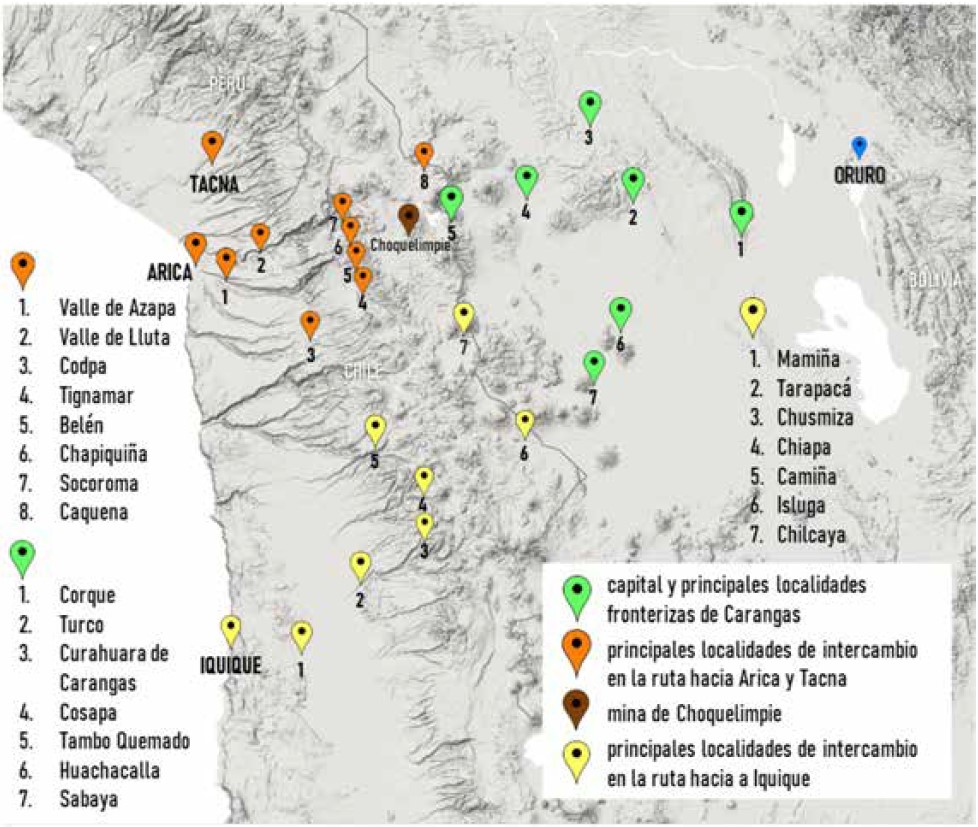

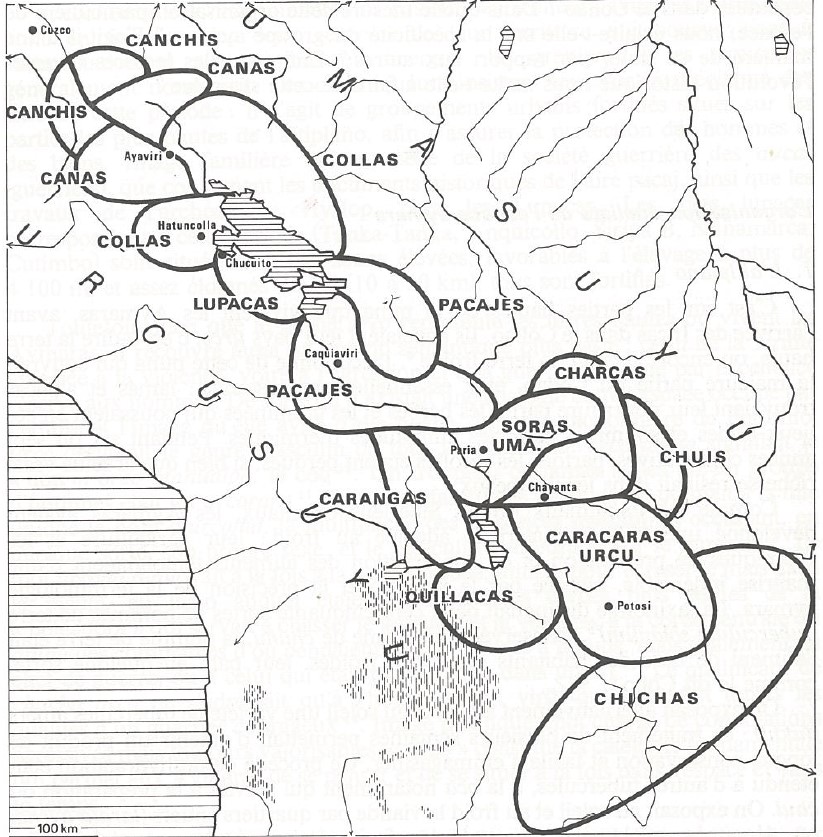

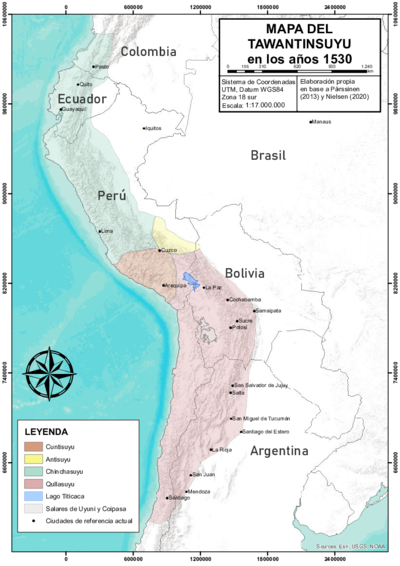

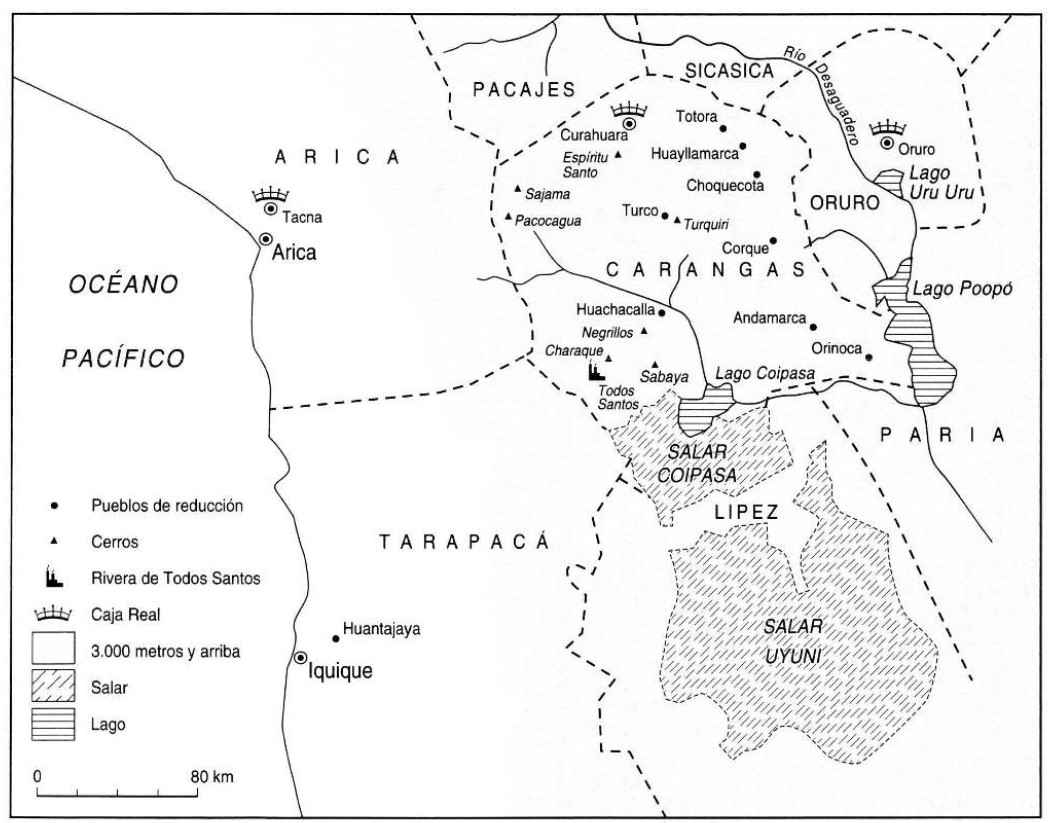

The map shows the changes and continuities in the cross-border mobility of the Aymara polity of the Karanqas Carangas) in the context of 19th century state formation and commercial expansion.1 Before the arrival of Spanish colonizers, in the 16th century, the Aymara polity of the Karanqas was part of the Qullasuyu, the southern district of the Inca state Tawantinsuyu. Following the model of ‘vertical control of ecological niches’ AYMARA POLITIES of THE QULLASUYU in the 16th CENTURY the territory of the Karanqas was located in the central western part of the high plateau yet it included ‘ethnic islands’ in the valleys west and east. After Bolivia and Chile established themselves as independent republics in the 19th century, the territory was divided between the two nations. Despite this division, Karanqas trans-border connections persisted and continue to exist today. The map, which is drawn upon a modern Google Earth image, shows the main Karanqas’ towns near the border with Chile and Perú, as well as the main towns that were part of the Karanqas’ route towards the Pacific (both towards Arica and Tacna as well as towards Iquique in present-day Chile) in the 19th century.

This map is noteworthy for its ability to capture the enduring trans-border nature of the Karanqas, persisting beyond the independence of Peru, Chile, and Bolivia, amidst the fluctuating dynamics influenced by events like the Pacific War. To some extent, these changes left the Karanqas isolated from the rest of the Bolivian Republic; however, their connection to the communities to the west remained being very important. Communities on both sides of these international borders sought to assert and accommodate their control over their grasslands, farmlands, and mines within the new national territorial boundaries2. The active commerce they maintained with each other was part of their strategy to respond to the changes.

The trans-cordilleran territories were especially relevant for the Karanqa, partly because of the ecological characteristics of the region which were those of a cold and dry climate. In fact, the altiplano and the western valleys are very close and connected (often more accessible than the eastern valleys), allowing a fluid transit and control between the two mountain slopes. In addition to the fact that the valleys at this latitude extend to the coast, facilitating transit to the Pacific. 3

While some scholars argue that these trans-cordilleran territories were strategically employed by the Karankas Aymara polity THE KARANQAS AYMARA POLITY UNDER SPANISH COLONIAL RULE IN THE 18TH CENTURY to effectively respond and resist to colonial pressures, it has also been argued that the Karanqas nucleus saw its connection with the Pacific enclaves diminish as indigenous organizational structures underwent fragmentation during colonization. 4 Further research is needed to fully comprehend how the Karanqas utilized access to these territories as part of their resilience strategies during the Spanish colonization period. Nevertheless, despite numerous changes, trans-border networks remain integral to contemporary Karanqas life.

REFERENCES:

Cajías de la Vega, F. Oruro 1781, sublevación de indios y rebelión criolla: vol I. La Paz: IFEA, 2005.

Cottyn, Hanne. “Entre Comunidad Indígena y Estado Liberal: los ‘Vecinos’ de Carangas

(Siglos XIX-XX).” Boletín Americanista 2, no. 65 (2012): 39-59.

Cottyn, H. “Global land commodification, national land reform and communal land tenure in Carangas (Bolivia), 19th -20th centuries”. Paper presented at the Rural History conference, Bern, 2013.

Cottyn, Hanne. “Carangas en Movimiento: Estado Liberal, Elites Provinciales y

Movilidad Transfronteriza Andina entre el Altiplano Boliviano y el Pacífico

(1860-1930).” Diálogo Andino 66 (December 2021): 261-272.

Gavira-Marquez, M. C. “Población Indígena, Minería y Sublevación en Carangas: La Caja

Real de Carangas y el Mineral de Huantajaya, 1750-1804”, Lima: Instituto Francés

de Estudios Andinos - CIHDE, 2008.

Michel, M. “El Señorío Prehispánico de Carangas.” Thesis of the Advanced Diploma in

Indigenous Peoples’ Law, Universidad de la Cordillera, La Paz, 2000.

Montero Montero, R. Gil. “Migración y Minería en el Corregimiento de Carangas (actual Bolivia), Siglo XVII.” Anuario de Historia de América Latina 55 (2018): 190-217.

Cottyn, Hanne. “Carangas en Movimiento: Estado Liberal, Elites Provinciales y Movilidad Trans- Fronteriza Andina entre el Altiplano Boliviano y el Pacífico (1860-1930).” Diálogo Andino 66 (December 2021): 261-272. ↩︎

Cottyn. “Carangas en Movimiento, 264. ↩︎

R. Gil Montero Montero, “Migración y minería en el corregimiento de Carangas (actual Bolivia), siglo XVII,” Anuario de Historia de América Latina 55 (2018): 190-217. ↩︎

M. C. Gavira-Marquez, Población Indígena, Minería y Sublevación en Carangas: La Caja Real de Carangas y el Mineral de Huantajaya, 1750-1804 (Lima: Instituto Francés de Estudios Andinos – CIHDE, 2008), 9. ↩︎