Abstract

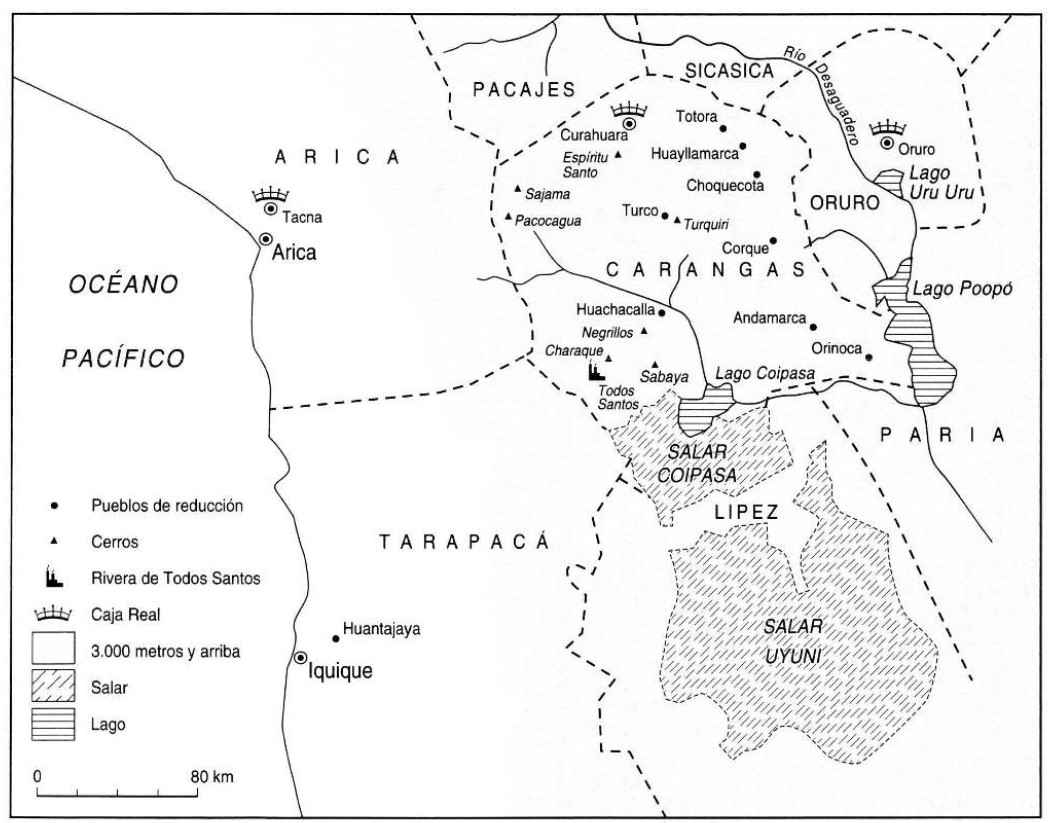

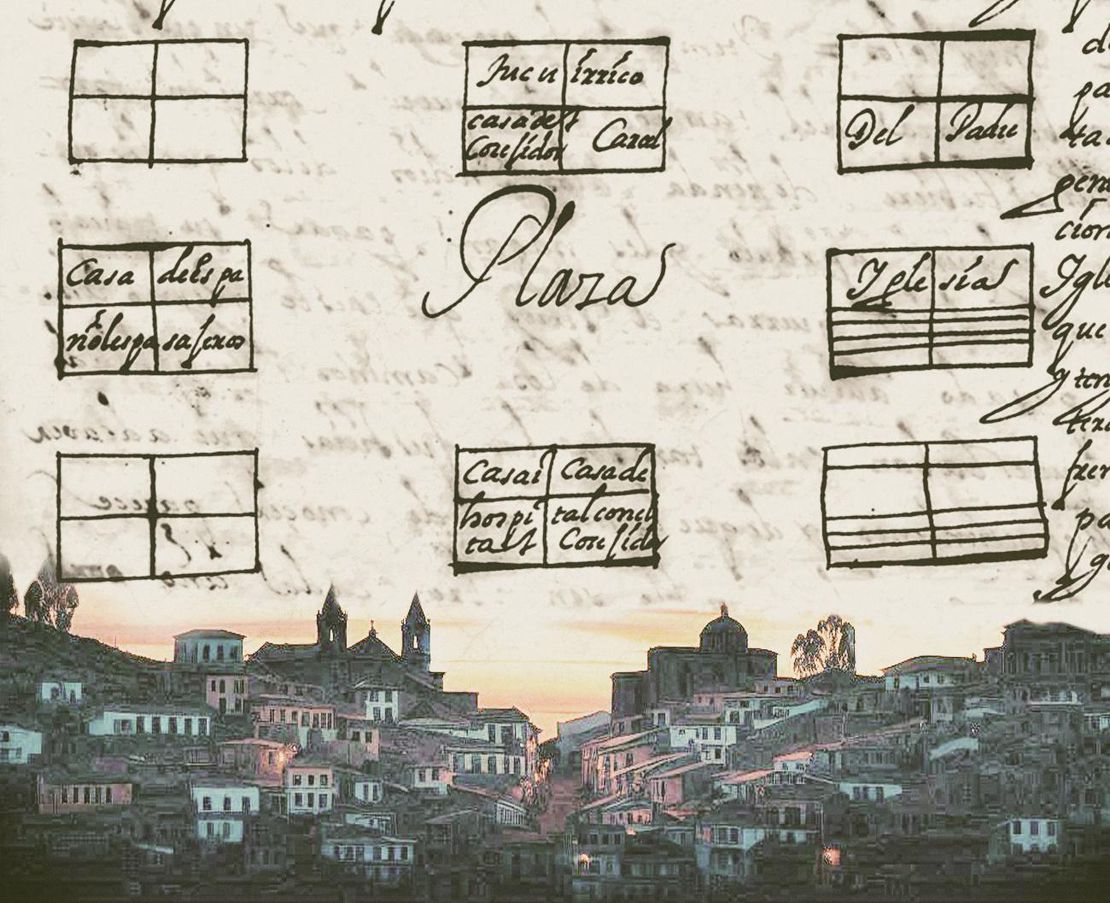

The map shows the nucleated ‘Indian Royal Towns’ established by the Spanish colonial state, through a massive forced resettlement program, in a portion of the territory of the Aymara polity of the Karanqas (or Carangas or Karankas) located in the central-southern region of the high plateau of present-day Bolivia. Before Spanish colonization, this area was part of the Qullasuyu, the southern district of the Inca state or Tawantinsuyu and it was the area in which the core settlements of the large Aymara polity of the Karanqas were located. Under Spanish colonial rule, the Qullasuyu became the southern district of the Viceroyalty of Peru called Distrito de la Audiencia de Charcas or La Plata divided into two large provinces, Charcas and La Paz. The area on the map was part of the former which was further divided into smaller territorial administrative units. The territorial units (sort of rural districts) assigned to the indigenous population were called Corregimientos de Indios. The area shown on the map became the Corregimiento of Carangas and encompassed a number of ‘Indian Royal Towns’ also called reducciones represented by the dots on the map.

The region was not really colonized until 1548 (after the civil wars); the first Spanish settlements were made by encomenderos COLONIAL LEGISLATION AS THE FRAMEWORK FOR DISPOSSESSIONS IN THE CENTRAL ANDES: THE ENCOMIENDA SYSTEM who, as collaborators in the conquest, were ‘given’ Indians from the region as a reward.1 Later, when Viceroy Toledo made the General Visit, or census, he found the Indians of the region divided according to whom they ‘belonged to’: to the Crown or to the encomenderos. In order to make better use of the labor force under the mita draft labor system Toledo organized districts. The region of Oruro was included within the district of La Plata or Audiencia de Charcas, a situation that was maintained until independence. The region was further subdivided into two large provinces: Paria and Carangas. Paria, in turn, was subdivided into three districts: Paria, Aullagas and Uruquillas, Quillacas and Azanaques while that of Carangas into four districts: Totora, Colquemarca and Andamarca, Chuquicota and Sabaya, and Urinoca.2

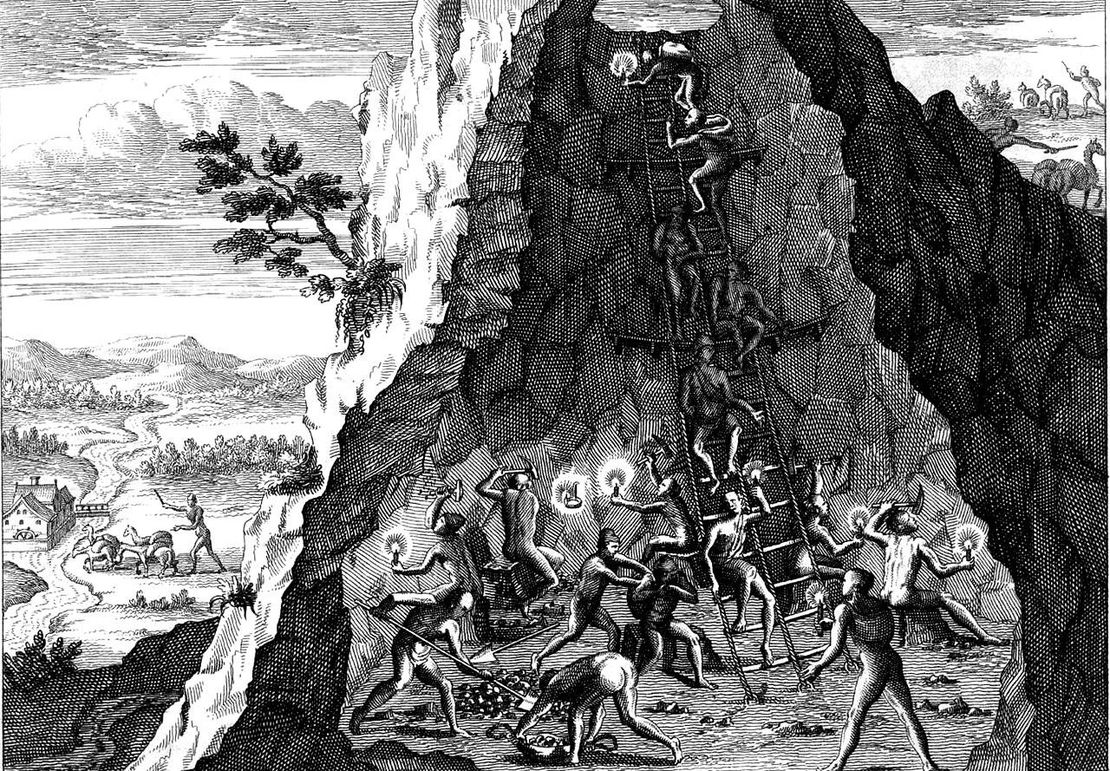

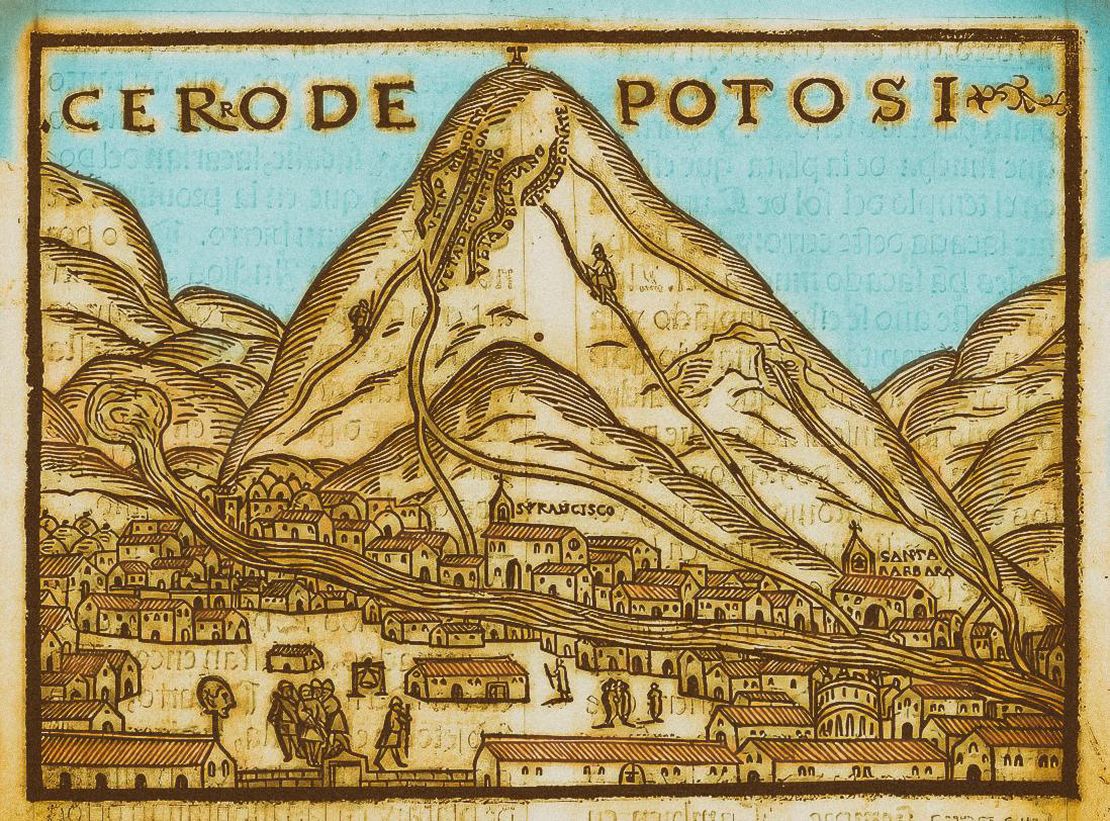

As a result of the implementation of the mita draft labor system in Potosí, Carangas was one of the most depopulated corregimientos of Charcas during the colonial period. While this trend was slightly reversed by the mid-17th century when silver veins were discovered in the Carangas territory , the impact of the mita on the Karanqas was profound.3 According to the information contained in the retasa de los tributos made by the Viceroy of La Palata in the 1680s from the general numeration, Carangas was a province that was in the approximate average by number of tributaries, but it was the one that effectively sent the greatest number of mitayos to Potosí. Comparative data between the Visita General of the 1570s and the general numeration of the Duke of La Palata give an account of the consequences of sending Karanqas mitayos to Potosí: “of the little more than 29,000 inhabitants that said viceroy [Toledo] registered in Carangas, there remained in 1683 something less than 8,000. If only the tributary population (males between 18 and 50 years old) is considered, this province, which had been the second most populated of Charcas in Toledo’s time, fell to the last place in this selection in La Palata’s time as a consequence of its depopulation. In 1683, however, it was the province that declared the most mitayos living in Potosí.”4 In general, subsequent visits showed that “the population curve continued to fall after Toledo’s administration for various causes: epidemics in the reducciones, the rigor of the mita work, absenteeism for not complying with the obligations imposed by the metropolis, etc. In other words, Toledo’s policy created the necessary conditions to continue the rapid decline of the native population.”5

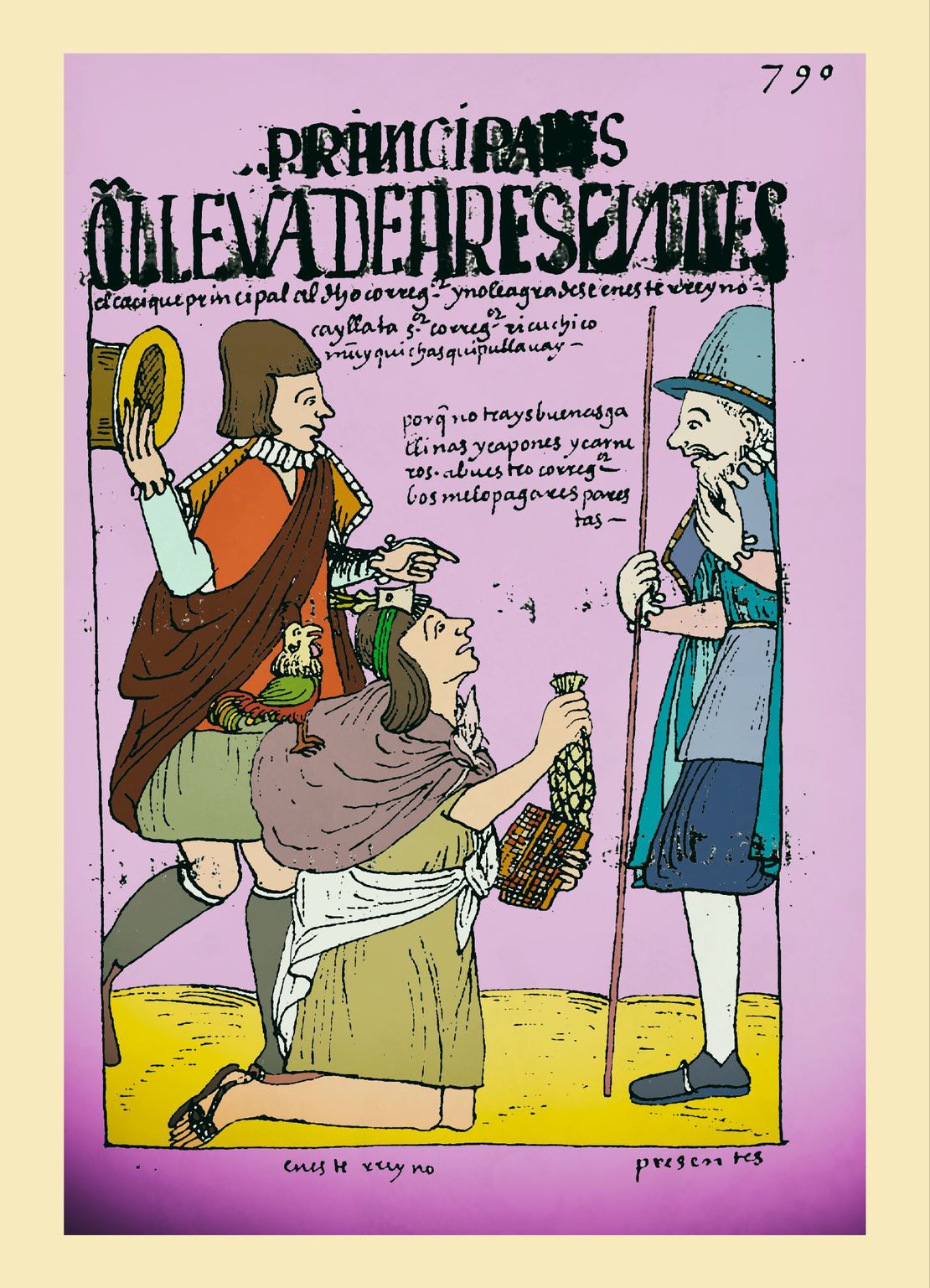

The Karanqas also had to pay tribute, which by 1551 was valued at “silver ($9000), abasca clothing, blankets, capotes, blankets, sacks, wool, sheep, tasajo, tallow, lard, partridges, hides, ojotas, salt, corn and potatoes, in addition to other minor products. They also had to serve as livestock guards for their encomenderos, provide them with Indians for service in La Plata, attend to the needs of the parish priests, and sow, benefit and harvest corn and wheat in the farms of their encomenderos in La Plata.”6 Later, at the time of the Toledo’s reform of the indigenous tribute criticisms were made about the excessiveness of the taxes; in any case, this was also one of the determining factors for the growing absenteeism that occurred in the communities, especially in the seventeenth century.7

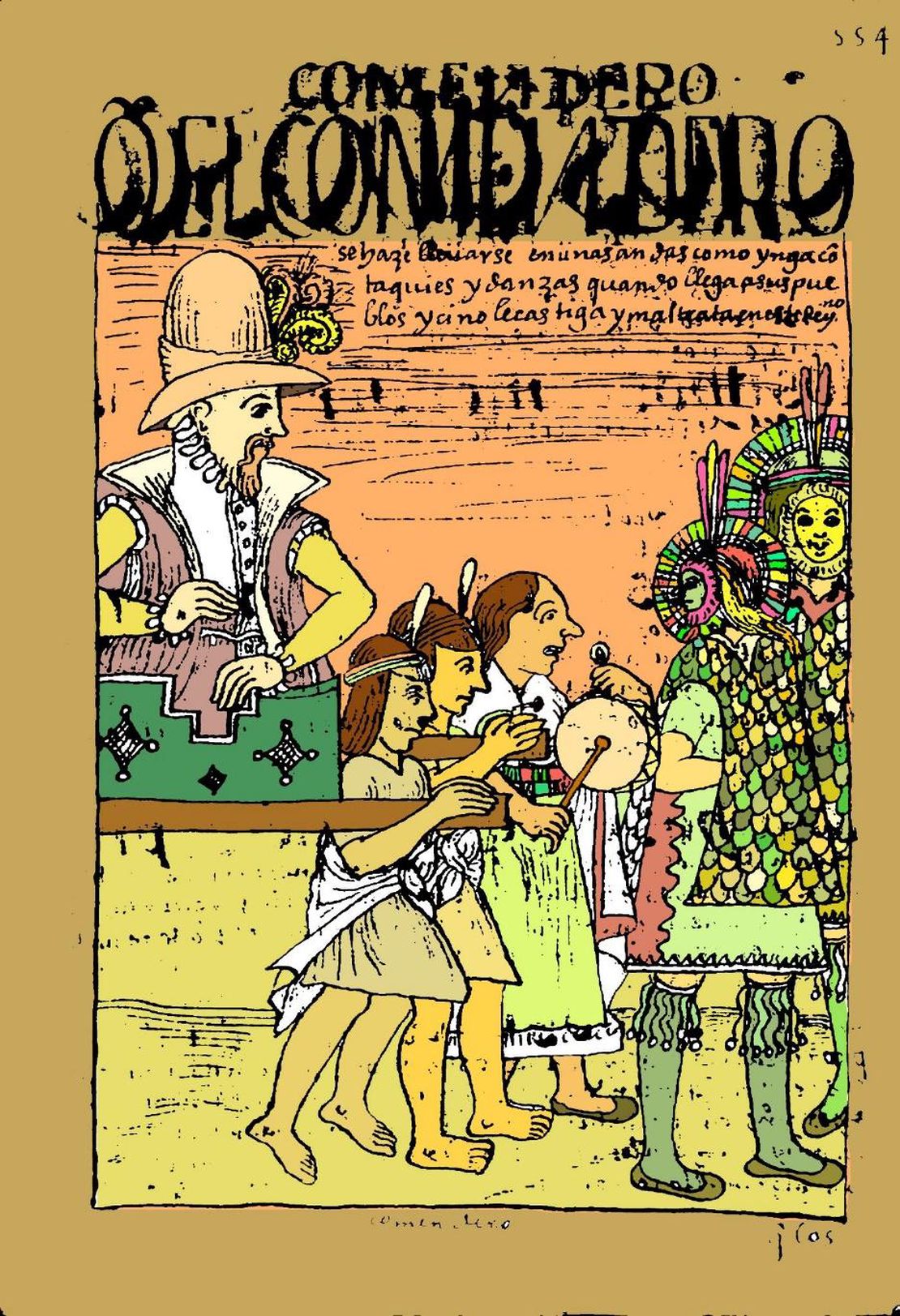

Another interesting angle to understand the processes of dispossession experienced by the Karanqas has to do with the early evangelization that took place in this territory by the Augustinians, dependent on the archbishopric of La Plata. While the evangelization enterprise itself was difficult (mainly because the vast majority of the clergy were ignorant of vernacular languages such as Pukina or Urukla), the fact that 16 churches were built in the Oruro region in the sixteenth century is evidence that the interest in evangelizing this area was a priority for the Spanish. 8 In fact, the churches of Carangas constitute one of the greatest testimonies of the colony and the Spanish civilizing process applied in the region.9

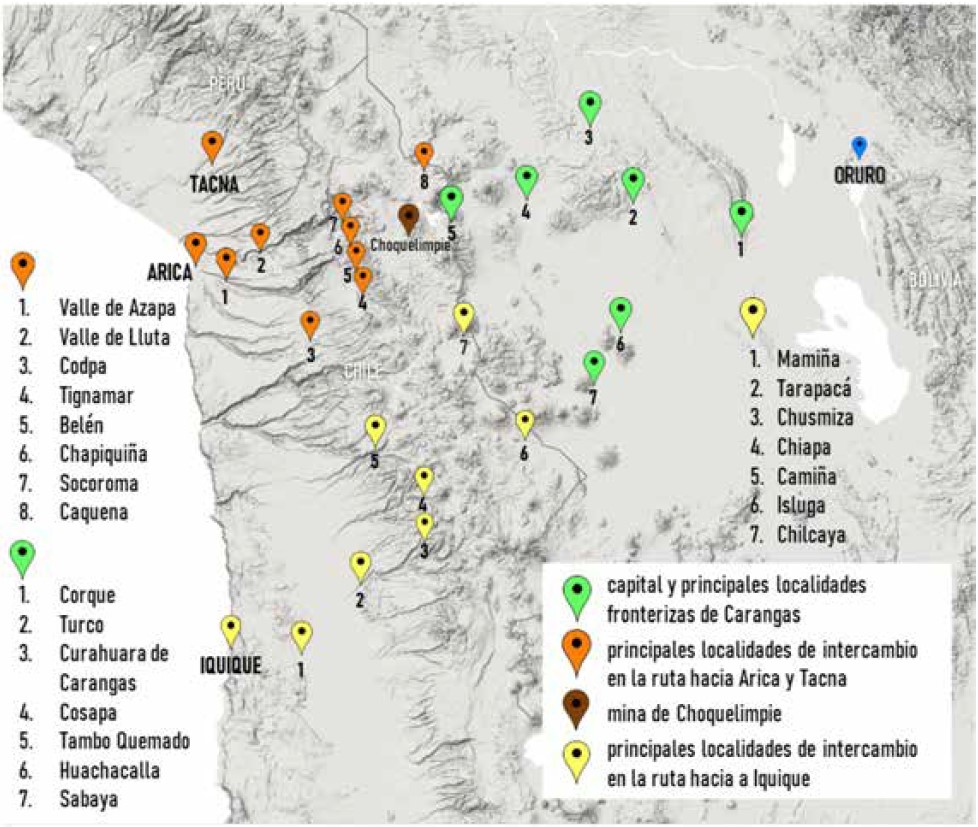

The impact of colonial institutions on the Karanqas structure also included the disconnection of their core territory from enclaves in Pacific valleys THE KARANQAS AYMARA POLITY - SNAPSHOT OF TRANS-BORDER CONNECTIONS AROUND 1900 (GOOGLE EARTH ADAPTATION) . This disconnection, stemming from the disruption of indigenous organization during conquest and colonization, led Karanqa authorities to lose control of settlements in these regions.10 By the 17th century, this dependence continued, but by the 18th century, a definitive break occurred due to Spanish and Creole advances from Arica seizing Karanqas lands for haciendas. This loss was compounded by a severe demographic decline in the early 18th century, which deprived Carangas of sufficient settlers.11

These developments, exacerbated by the repartos , contributed to fertile conditions for indigenous uprisings across the region. Despite limited sources, evidence suggests significant indigenous involvement in these uprisings, reflecting responses ranging from peaceful resistance to active rebellion, such as seen in the Llanquera community in 1732 and participation in the larger Tupac Amaru uprising of 1781.12

REFERENCES:

Bouysse-Cassagne, T., and J. Chacama. “Partición Colonial del Territorio, Cultos

Funerarios y Memoria Ancestral en Carangas y Precordillera de Arica (siglos

XVI-XVII).” Chungara: Revista de Antropología Chilena 44, no. 4 (2012):

669-689.

Cajías de la Vega, Fernando. Oruro 1781, Sublevación de Indios y Rebelión Criolla: vol

I. La Paz: IFEA, 2005.

Gavira-Marquez, M. C. “Población Indígena, Minería y Sublevación en Carangas: La Caja

Real de Carangas y el Mineral de Huantajaya, 1750-1804”, Lima: Instituto Francés

de Estudios Andinos - CIHDE, 2008.

Michel, M. “El Señorío Prehispánico de Carangas.” Thesis of the Advanced Diploma in Indigenous Peoples’ Law, Universidad de la Cordillera, La Paz, 2000.

Montero Montero, R. Gil. “Migración y Minería en el Corregimiento de Carangas (actual Bolivia), siglo XVII.” Anuario de Historia de América Latina 55 (2018): 190-217.

Fernando Cajías de la Vega, Oruro 1781, Sublevación de Indios y Rebelión Criolla: vol I. (La Paz: IFEA, 2005), 25. ↩︎

Cajías de la Vega, Oruro 1781, 25. ↩︎

R. Gil Montero Montero, “Migración y Minería en el Corregimiento de Carangas (actual Bolivia), Siglo XVII,” Anuario de Historia de América Latina 55 (2018): 200. ↩︎

Montero Montero, Migración y Minería en el Corregimiento de Carangas, 200. ↩︎

Cajías de la Vega, Oruro 1781, 28 ↩︎

Montero Montero, Migración y Minería en el Corregimiento de Carangas, 202. ↩︎

Cajías de la Vega, Oruro 1781, 191. ↩︎

Thérèse Bouysse-Cassagne and Juan Chacama. “Partición Colonial del Territorio, Cultos

Funerarios y Memoria Ancestral en Carangas y Precordillera de Arica (siglos XVI-XVII)”. Chungara: Revista de Antropología Chilena 44, no. 4 (2012): 671. ↩︎M. Michel, “El Señorío Prehispánico de Carangas.” (Thesis of the Advanced Diploma in Indigenous Peoples’ Law, Universidad de la Cordillera, 2000), 82. ↩︎

M. C. Gavira-Marquez, Población Indígena, Minería y Sublevación en Carangas: La Caja Real de Carangas y el Mineral de Huantajaya, 1750-1804 (Lima: Instituto Francés de Estudios Andinos – CIHDE, 2008), 9. ↩︎

Cajías de la Vega, Oruro 1781, 42. ↩︎

Gavira-Marquez, Población Indígena, Minería y Sublevación en Carangas, 85. ↩︎