Abstract

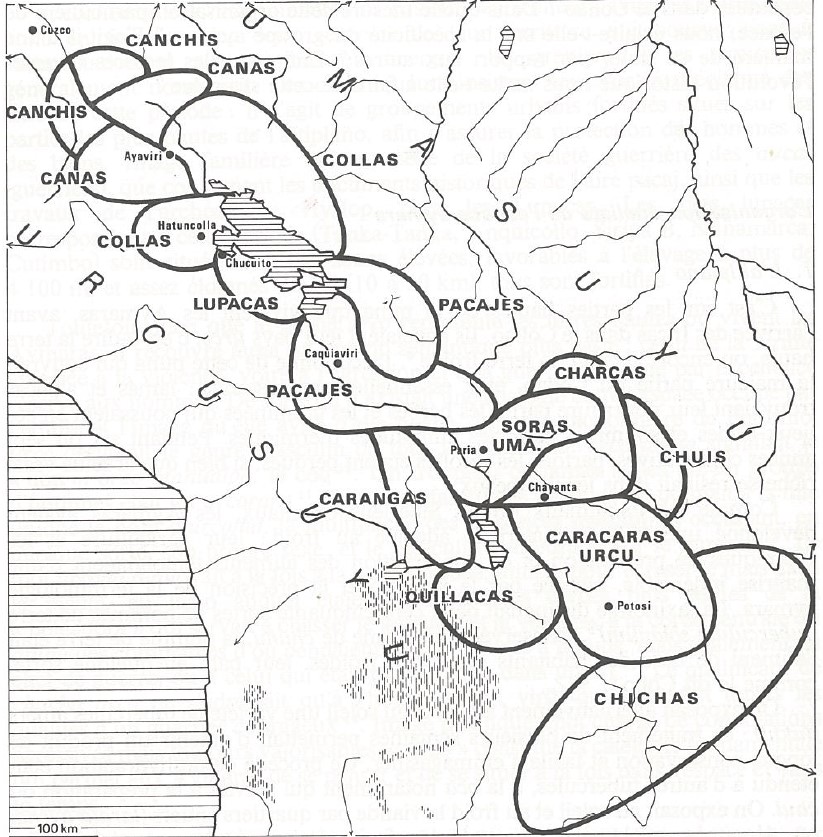

The map based on primary and secondary sources depicts the territory of the Killakas confederation (also known as Killaqas, Quillaqas or Quillacas).1 In the years before the beginning of the colonial period, the territory of this Aymara lordship, which was part of the Qullasuyu—southern district of the Inca state—, was located southeast of Lake Poopó. Based on the model of vertical control of ecological niches and discontinuous territoriality AYMARA POLITIES of THE QULLASUYU in the 16th CENTURY , the Killakas were in the altiplano, southeast of Lake Poopó, and in ecological niches along the inter-Andean valleys of present-day southeastern Bolivia. The main reforms implemented by the colonial state in the 1570s forced the relocation of their scattered settlements into six clustered towns whose geographic and identity references have been preserved to this day.

The space had been organized in such a way that each of the nations that made up this federation had a separate territory. The Asanaque peoples would be located northeast of the territory, the Killaka and Aullagas-Urukillas had been transferred to the center, and the Sevaruyos and Aracapis to the south, in what would be known as the Corregimiento de Porco during colonial times. The map displays several references of heights above sea level, peaks, salt flats, rivers, Spanish towns, reductions, and islands in the valleys.

The Killakas were mainly camelid herders, but would additionally practice agriculture. They were also skilled at working in the mines. This is why they would work on the mineral veins and seams along with other groups, as mines had become multi-ethnic spaces under Inca state control. They also exploited salt. The western part of their territory included the Coypasa salt flats and a small part of the Uyuni salt flat. They had the Urmiri salt mines to the southeast, and in colonial times, they would also possess those of Yocalla. Salt would become a universal barter commodity. Since they also raised llamas throughout their territory, they would travel in convoys of hundreds of animals loaded with salt, heading to the valleys to trade them for corn, fruits, honey and other products that complemented their staple diet.2

Many studies have been conducted on land acquisition strategies and the commercialization of salt, a staple product in the town of Potosí. 3 These papers have analyzed the mechanisms that the Killakas put into play not only to preserve their pre-Hispanic territory, but also to expand it by resorting to great creativity, as the pre-Hispanic territory would undergo a series of rearrangements, gains and losses, while adopting the mercantile system that the crown imposed.

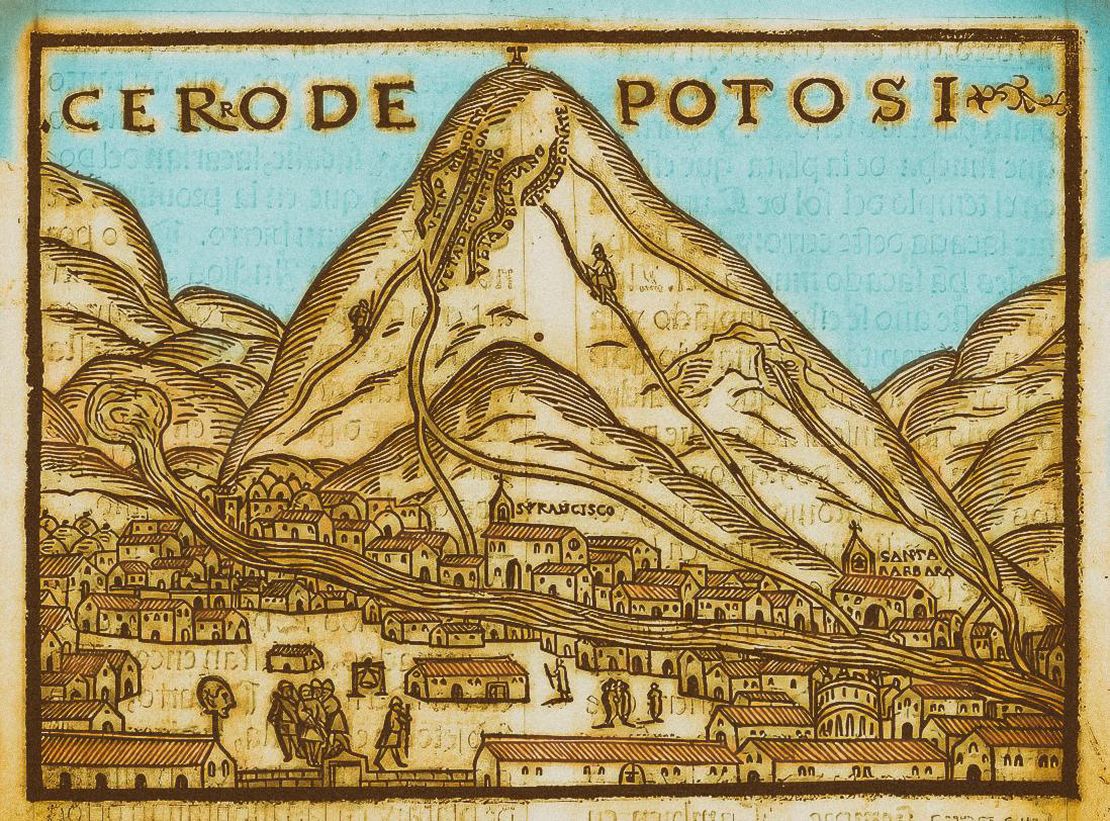

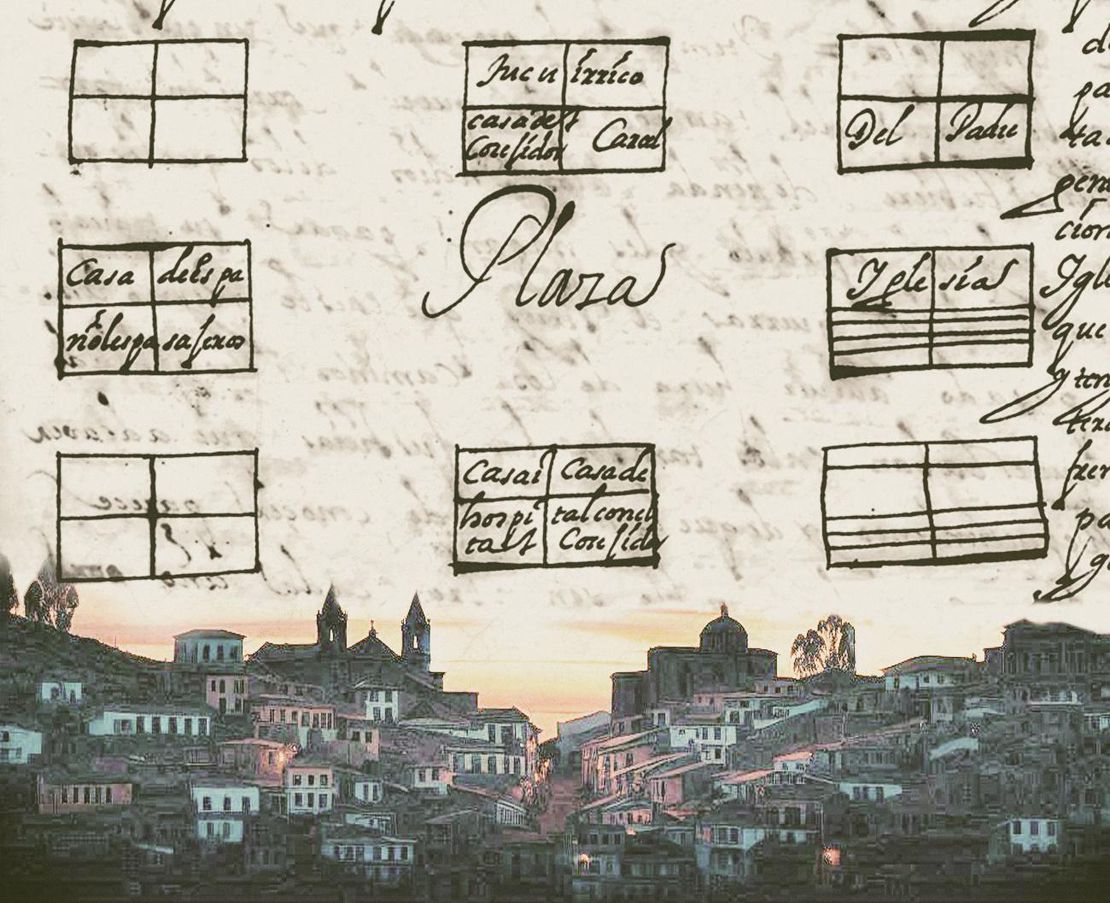

With the “discovery” of the veins of Potosí, the Killakas were integrated in the mining activity early on. With Toledo´s reforms in the 1570s, they had to observe the mandatory mita service along with 15 other provinces.4 Their kuraka —an Indigenous authority—, who became Captain of the Mita system, was the most powerful Andean kuraka in Toledo´s time, the only Indigenous owner of a mining mill, who would have a noticeable influence in the enactment of ordinances during Toledo´s term, added to his participation in the economy through the metals trade and proceeds. This implied the presence of four things: a) a significant start-up capital to install a mill; b) contacts with the colonial power; c) labor force; d) —perhaps the most important factor—, “having a mindset that allowed him to successfully articulate, from early in the Colonial Period, the community-based economy with the market economy.” 5

The Killakas sought to consolidate and expand their territory. They controlled access to the salt mines of Yocalla —Potosí supplier—, as well as to grasslands and pastures where they could raise huge herds of llamas that would transport the salt from the mines to the mills. Their location was therefore superb to take advantage of the developments in Potosí. In turn, the Asanaque possessed a discontinuous territory that was mainly located in two blocks on both sides of the mining territory of Porco and Potosí. Salt became a profitable business, since employing the blending technique with mercury or quicksilver to obtain purer silver, required large quantities of salt, in addition to that needed for human and animal consumption in Potosí. The proceeds derived from the large transaction volumes, and above all, from the transportation. This business favored several Spaniards, but the sale and transportation of the salt began to be one of the most important income sources for the Killakas, as the control of livestock remained in their hands. 6

The llameros Killakas embodied the transition from an “ethnic model” to a market economy. They not only handled early on the equivalences in the goods exchange, but also incorporated the concept of the value of socially necessary work expressed in the management of their animals for transporting salt and minerals, which definitely “added value to their merchandise or barter goods. With this cultural legacy, and together with other deeply religious and ritualistic roots […] they decided to challenge the new system.”7 Everything seems to indicate that the wealth that the Kurakas Killakas began to earn was used in the purchase of land. Hence the large number of possessions acquired in colonial times, both in the form of private estates of the kurakas as well as communal lands.

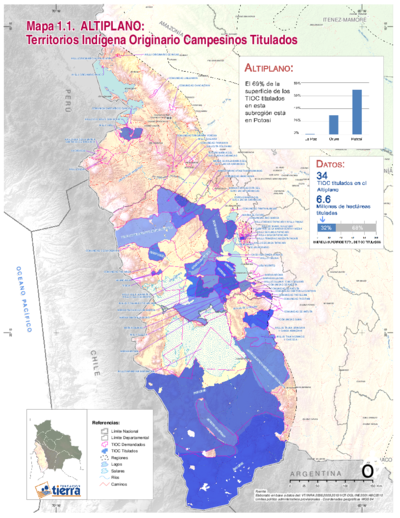

The republican state brought about new territorial governance structures that triggered historical territorial conflicts over interdepartmental borders that to this day have not been resolved between the Killakas of the Department of Potosí and the Killakas of the Department of Oruro. As of the Land Reform, peasant unionization was accelerated and private land titling enforced as required by law since 1953.8

The native authorities of the ayllus came together in the town of Santuario de Quillacas, capital of the Jatun Killaka Native Nation —as they would call themselves—, with the engagement of their community members and native authorities, and resolved the creation of the Federation of the Ayllus of Southern Oruro (FASOR). In 1997, they consolidated the Indigenous movement of the native nations in Bolivia as a federal representation with territorial jurisdiction in the highlands, to exercise their governance and territorial organization until today.9

According to administrative political references of the Bolivian state, and within the Plurinational State of Bolivia, the Jatun Killaka Indigenous Nation is located across the provinces of Eduardo Avaroa, Sebastián Pagador and Ladislao Cabrera. It consists of 74 *ayllus —*six of them in the process of reconstruction— and more than 1,000 communities. It is governed by a Native Executive Council in accordance with its own territorial organization systems and structures. Until 2011, 54 ayllus, communities or associations had applied for their status as TIOCS (Territorios Indígenas Originarios Campesinos), of which 44 titles have been conferred so far.10 According to official data from 2007, the territory of the Jatun Killakas Native Nation covers a surface area of 14,805 Km2 —representing 30.28% of the departmental territory—, and is home to a population of 49,594 inhabitants, equivalent to a population density of 3.35 inhabitants/km2.11

In the first decades of the 21st century, the Killaka macro-identity has endured as a long-lasting memory. Each ayllu and community accepts this political and cultural sense of belonging, in the same way that its inhabitants acknowledge their belonging to a peasant or farmers union structure.

REFERENCES:

Abercrombie, Thomas. Caminos de la Memoria y del Poder. Etnografía e Historia de

una Comunidad Andina. La Paz: IFEA - IEB, 2006.

Barragan, Rossana and Molina, Ramiro. De Señoríos a Comunidades, El Caso del Señorío

Quillaca. La Paz: MUSEF, 1987.

Platt, Tristan. “Acerca del Sistema Pre-Toledano en el Alto Perú.” Avances 1 (1978):

33-46.

Fundación Tierra. Territorios Indígenas Originarios Campesinos en Bolivia. Entre la

Loma Santa y la Pachamama, La Paz: Fundación Tierra, 2011.

Medinaceli, Ximena. “Los Quillacas, Potosí y la Sal: Formas Culturales de Transición de un Sistema de Intercambio a otro Mercantil.” In Mina y Metalurgia en los Andes del Sur, desde la Epoca Prehispánica hasta el Siglo XVII, edited by Pablo Cruz and Jean Joinville Vacher, 279-301. Lima, Peru: IRD-IFEA, 2008.

Medinaceli, Ximena. Sariri: Los Llameros y la Construcción de la Sociedad Colonial. La Paz: IFEA-Plural, 2010.

Michel López, Marcos. Patrones de Asentamiento Precolombino del Altiplano Boliviano Lugares Centrales de la Región de Quillacas, Departamento de Oruro, Bolivia [doctoral thesis] (La Paz: Universidad Mayor de San Andrés; Uppsala: Department of Archaeology and Ancient History- Uppsala University, 2008).

Tristan Platt. “Symétries en Miroir: Le Concept de Yanantin chez les Macha de Bolivie.” Annales E.S.C. 33, 5-6 (1978): 1081-1107.

Native Nation Suyu Jatun Killaka Asanajaqi. Historia de la Nación Originaria Suyu Jatun Killaka, 2013. Retrieved from http://suyujatunkillaka.blogspot.com/ (revised 9-11-2022).

Andina. (La Paz: IFEA - IEB, 2006), 157; Tristan Platt. “Symétries en Miroir: Le Concept de Yanantin chez les Macha de Bolivie”. Annales E.S.C. 33, 5-6 (1978), 1081-1107.

Andina. La Paz: IFEA – IEB, 2006).

la Pachamama (La Paz: Fundación Tierra, 2011).

Thomas Abercrombie. Caminos de la Memoria y del Poder. Etnografía e Historia de una Comunidad ↩︎

Marcos Michel López. Patrones de Asentamiento Precolombino del Altiplano Boliviano Lugares Centrales de la Región de Quillacas, Departamento de Oruro, Bolivia [doctoral thesis] (La Paz: Universidad Mayor de San Andrés; Uppsala: Department of Archaeology and Ancient History Uppsala University, 2008). ↩︎

Ximena Medinaceli. “Los Quillacas, Potosí y la Sal: Formas Culturales de Transición de un Sistema de Intercambio a otro Mercantil.” In Mina y Metalurgia en los Andes del Sur, desde la Epoca Prehispánica hasta el Siglo XVII, ed. Pablo Cruz and Jean Joinville Vacher (La Paz, Lima: IRD-IFEA, 2008), 279-301. ↩︎

Medinaceli, “Los Quillacas, Potosí y la Sal; Ximena Medinaceli, Sariri: Los Llameros y la Construcción de la Sociedad Colonial” (La Paz: IFEA-Plural, 2010). ↩︎

Medinaceli. “Los Quillacas, Potosí y la Sal,” 285. ↩︎

Rossana Barragan and Ramiro Molina. De Señoríos a Comunidades, El Caso del Señorío Quillaca. (La Paz: MUSEF, 1987); Medinaceli. “Los Quillacas, Potosí y la Sal”. ↩︎

Medinaceli. “Los Quillacas, Potosí y la Sal,” 299. ↩︎

Thomas Abercrombie. Caminos de la Memoria y del Poder. Etnografía e Historia de una Comunidad ↩︎

Native Nation Suyu Jatun Killaka Asanajaqi. Diagnostico Territorial Jatun Killaka, Muyt’a, 2013. Retrieved from http://suyujatunkillaka.blogspot.com/ (revised 9-11-2022). ↩︎

Fundación Tierra. Territorios Indígena Originario Campesinos en Bolivia. Entre la Loma Santa ↩︎

Nación Originaria Suyu Jatun Killaka Asanajaqi. Diagnostico Territorial Jatun Killaka. ↩︎

![Abercrombie, T. ([1998] 2006). Caminos De la memoria y del poder. Etnografía e historia de una comunidad andina. IFEA, IEB, ASDI.](https://dnet8ble6lm7w.cloudfront.net/maps/BOL/BOL0038.png)