Abstract

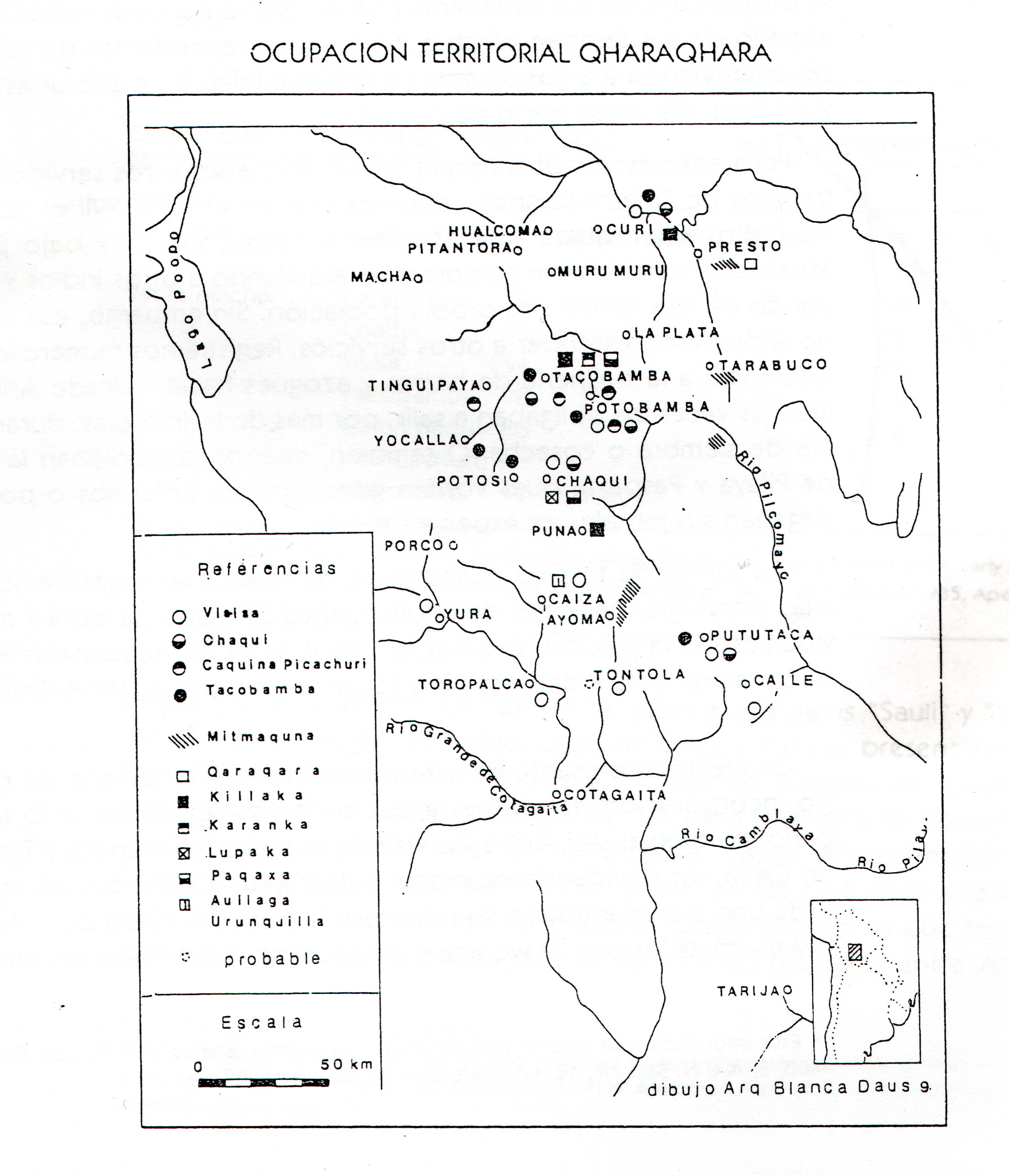

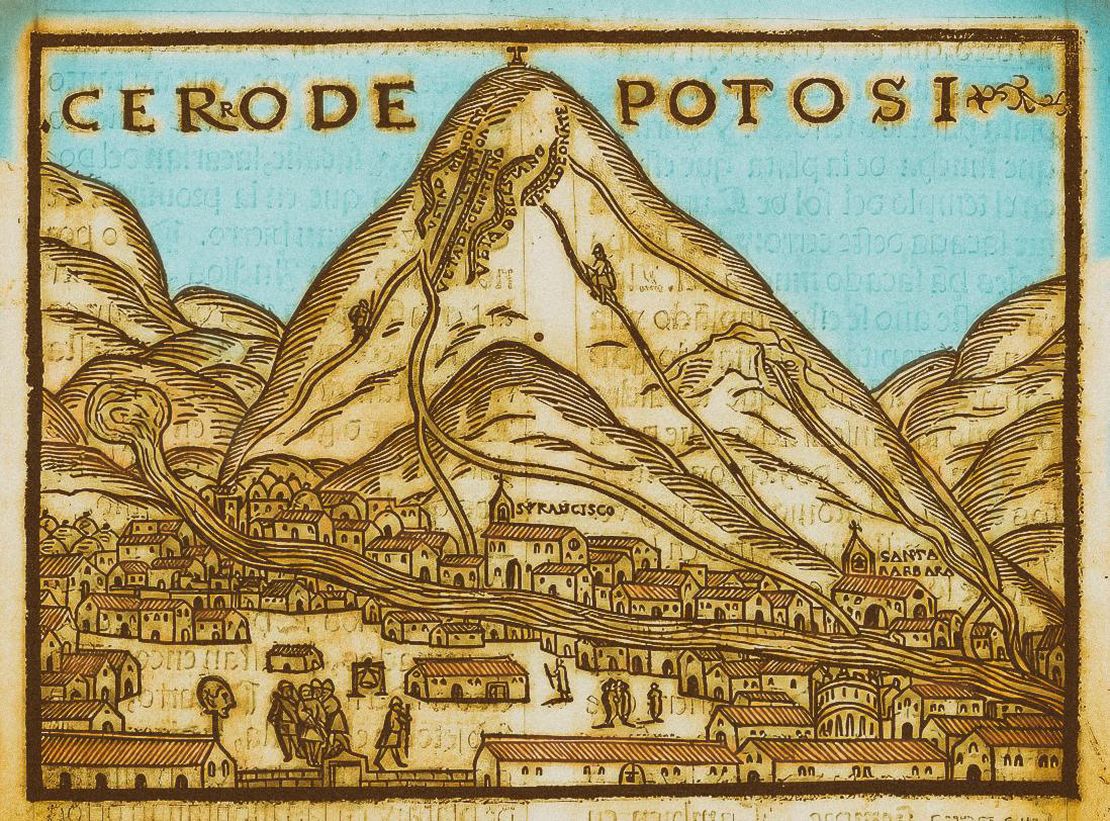

The map displays the territorial occupation of the Aymara lordship AYMARA POLITIES of THE QULLASUYU in the 16th CENTURY of the Qaraqara (also found as Qharaqhara or Caracara), which in the 16th century was part of the Qullasuyu, southern district of the Inca state or Tawantinsuyu.1 Located in the southeastern part of present-day Bolivia. This territory included “ethnic islands” in the inter-Andean valleys east of the altiplano. In fact, following the model of vertical control of ecological niches distinctive of this part of the Andes, the territories of the Aymara lordships were discontinuous, forming a sort of “vertical archipelagos.”2 It is worth mentioning that the silver mines of Potosí were part of this territory, standing as the most important economic hub of the viceroyalty of Peru.

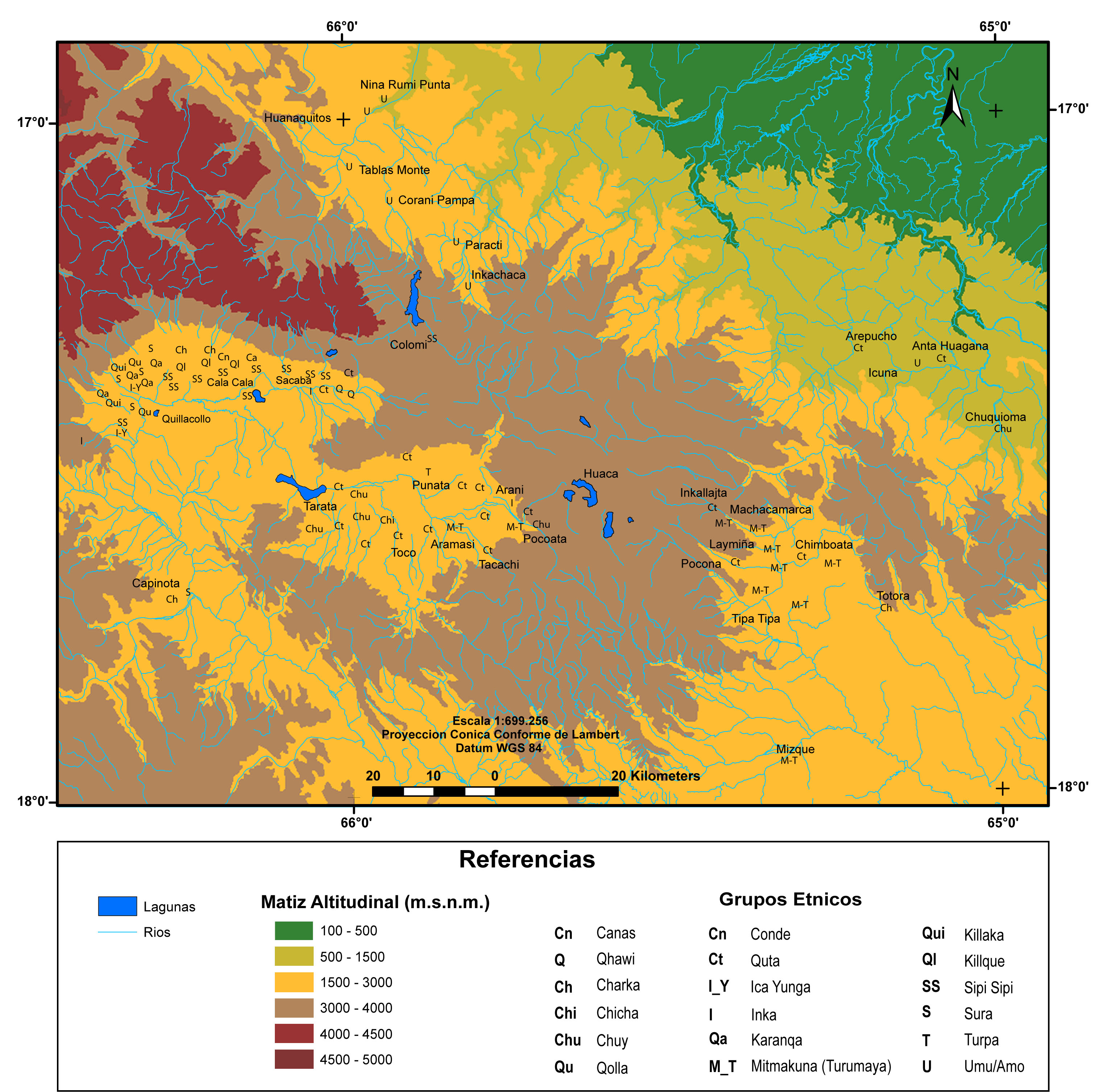

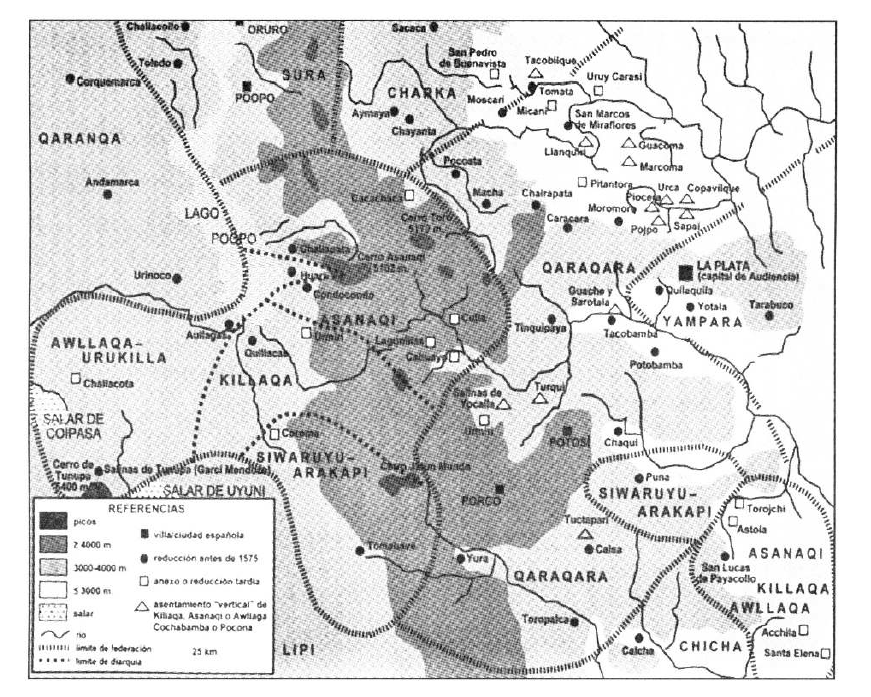

The Aymara polities called Aymara lordships AYMARA POLITIES of THE QULLASUYU in the 16th CENTURY , were formed by “confederated lineages” or, more precisely, sets of congregated kinship groupings or ayllus. Both in Qhishwa —the language used by the Incas— and in Aymara, the word ayllu, translated as “grouping” or “lineage,” indicates social organizations differing in size and complexity. In its smallest expression, an ayllu consisted of an extensive network of households and stood as the cell of pre-colonial Andean societies. The grouped structure of the ayllus was also expressed in the social organization of vertical space. Thus, the Qaraqara ethnic structuring was organized in a set of ayllus, occupying the territory between the socio-political unit of the Charka to the north AYMARA LORDSHIPS OF THE CHARKA AND NEIGHBORING NON-AYMARA POLITIES IN THE LATE 15th AND EARLY 16th CENTURIES , the Killaka to the west TERRITORY OF THE AYMARA LORDSHIP OF THE KILLAKAS IN THE EARLY 16TH CENTURY ,and the Chichas to the south THE LANDS OF THE AYMARA LORDSHIP OF THE CHICHAS DE TALINA UNDER COLONIAL RULE IN THE LATE 16TH CENTURY , in addition to the non-Aymara lordship of the Chuis, to the northeast.

In the first decades of the 16th century, this socio-political unit was grouped into two subdivisions or partitions: half Macha and half Chaqui, located between the current departments of Potosí and Chuquisaca.3 The map also shows the presence of mitmaqkunas, groups coming from other Aymara lordships AYMARA POLITIES of THE QULLASUYU in the 16th CENTURY in Qaraqara territory that had been relocated by the Inca state to other areas of its territory, fulfilling economic, political and military functions.

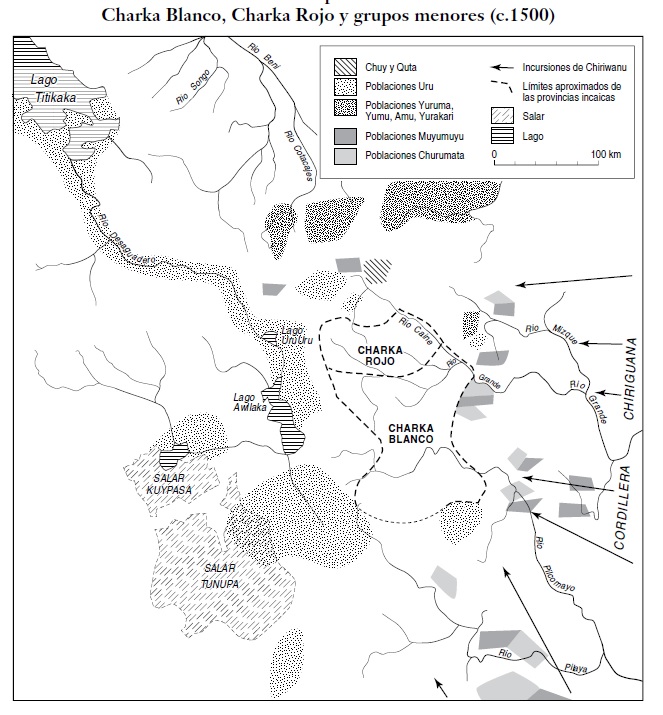

Ethnohistorical studies have proposed that at the time of the Inca Wayna Qhapaq, in the early 1500s, there was a differentiation between the White Charka and the Red Charka Provinces.4 The former would later become the Qaraqara province and the latter, the Charka, which means that the name “Qaraqara” was incorporated later on, and is probably of Inca origin. Finally, the phrase “Charcas Indians” includes —as per records in colonial documents—, the alliance of both federations, Qaraqara and Charka AYMARA LORDSHIPS OF THE CHARKA AND NEIGHBORING NON-AYMARA POLITIES IN THE LATE 15th AND EARLY 16th CENTURIES respectively.5

The Incas did not interfere too much in the Qaraqara political structures, but they reinforced their control grip by having their local lords take on pledges —for example—, through marriage unions, in order to exercise indirect rule over them.6 This was additionally reinforced through the presence of the Cusco administrative apparatus, which incorporated a considerable number of mitmaqkuna, or groups relocated by the Inca, which fulfilled military and socioeconomic functions. Through this political apparatus, they were able to yield income for the state, without exerting excessive tax pressure on the groups in each region. Many Qaraqara inhabitants were sent as mitmaqkunas to other regions of the empire, as was the case in the Cochabamba valley.7 MULTI-ETHNIC TERRITORY under INCA DIRECT RULE: THE CENTRAL AND UPPER VALLEYS OF COCHABAMBA in the 1530s

The disruption conducted by the Spaniards on the complex network of kinship and political hierarchies of these groups was so forceful that it affected the macro-level sociopolitical unity. Some authors have observed two degrees of ethnic disarticulation. The first one affected the authority systems at the level of the lordship chiefdoms at large, and the second one operated at the level of the two great partitions, major ayllus, with a lesser effect towards the interior of each ethnic group and minor ayllu. At this level, a range of survival strategies were articulated, which nevertheless impacted the traditional lifestyle reproduction patterns to varying degrees. However, del Río concludes “that there was an Indigenous matrix that is constantly reproduced and recreated in the group, ayllu or community and that survived throughout the historical sequence up to the present day.”8

In the 1570s, Viceroy Toledo assigned the Qullasuyu Indians to forced shift-labor in the so-calledmita system, within the mines of Potosí system. Some studies indicate that in the 17th century, the percentage of Qaraqara Indians who went to Potosí was very low, because their authorities left this obligation without effect by hiring other Indians, thus protecting their own population.9 However, this strategy could not be extended to other services, such as the transport of silver bars and quicksilver to and from Arica, or the guarding of the southern border. These mandatory shifts and the demographic losses due to epidemics, coupled with the phenomenon of Indians fleeing their communities in response to excessive tax obligations during the 17th century, impacted the ethnic structuring of the Aymara lordships throughout the region.

As del Río has pointed out, one of the effects of this situation —which can be verified in the case of Qaraqara— was the incorporation of new ayllus into the communities. Thus, some ayllus would include two ayllus in one within the Reductions system; or the formation of new ones as the result of strong migrations that affected the region.10 In this context, the mallku —Indigenous political authority— became the axis around which political decisions leading to the shaping of identity processes were made.

The Land Alienation laws adopted in the second half of the 19th century during the republican period sought the extinction of the ayllus, private land ownership and the imposition of a new tax system, along with the conversion of the communal Indian into a settler, tenant farmer and small landowner. These laws failed to have these effects on the ayllus that belonged to the Qaraqara-Charka confederation, which continued to own territories with their nuclei in the highlands and their “islands” in the valleys. Expansion possibilities for hacienda owners in the region were limited, as compact communities surrounded them. Even the mestizo neighbors of the towns allied themselves with the ayllus when faced with the threat of expropriation of their own lands. The provincial and departmental authorities disagreed with a tax reform that would take away the main income in the departmental coffers in exchange for an uncertain “cadastral tax,” enshrined in the law, which even the hacienda owners were unwilling to pay.11

With the Land Reform of 1953, some communities legitimated their lands on an individual basis since collective tenure was no longer recognized, which resulted in their organizations migrating to unionization. The ayllus, in possession of colonial documentation records, persisted with collective land titles, and based on this form of organization, sought to legalize their territory according to existing legislation. With Act 1551 of Popular Participation (1994), many Qaraqara ayllus were forced to reorganize as grassroots territorial organizations and adapt as municipal districts. In that same year, many Qaraqara ayllus participated in the establishment of the National Council of Ayllus and Markas of the Qullasuyu .12

Act 1715 dated 1997 opened and promoted the Indigenous rural land market. Despite this, it still recognized the Community Lands of Origin (“Tierras Comunitarias de Origen” – TCO as per acronym in Spanish). Back then, the strategy consisted in participating in an organized way at the regional and national levels, so that the Qaraqara ayllus could engage in the foundation of the Council of Original Ayllus of Potosí, an institution for which they would develop legal basis and grounds, legal status, testimonials, memorial logs, etc. and it was determined that the path towards reconstitution would be the “saneamiento”, clearance and adoption as Community Lands of Origin. 13

Although the Memorial de Charcas (1582), a fundamental document on the history of Qaraqara, recognizes the existence of eight ayllus, six have been reorganized at present, two of which were subordinated to republican structures. They are still discontinuous territories, small ayllus that have created a wide range of kinship networks with other ayllus, or have ended up legalizing their lands on an individual basis. 14

REFERENCES:

Bouysse-Cassagne, Thérèse. “L’Espace Aymara: Urco et Uma.” Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales 33, no. 5-6 (December 1978): 1057-80. https://doi.org/10.3406/ahess.1978.294000.

Del Rio, Mercedes. “Estrategias Andinas de Supervivencia: El Control de Recursos en Chaquí.” In Espacio, Etnias, Frontera, compiled by Ana María Presta, 3-47. Sucre, Bolivia: ASUR, 1995.

Flores Cruz, Samuel, and Stalin Gonzalo Herrera. Caso 110: Las Luchas de los Ayllus Quila Quila Marka. CIUDAD: Movimiento Regional por la Tierra, 2017.

Ibáñez Ferrufino, Ramiro. “Limitaciones en el acceso al sistema de justicia boliviano de la jurisdicción indígena originaria campesina Qhara Qhara Suyu y los desajustes en la cooperación y coordinación,” en Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación, 19, 24 (2021), 87 – 112.

Murra, John. Formaciones Económicas y Políticas del Mundo Andino. Lima: IEP, 1975.

Platt, Tristan, Bouysse-Cassagne, Thérèse, & Harris, Olivia. Qaraqara-Charka: Mallku, Inka y rey en la Provincia de Charcas (siglos XV – XVII): Historia Antropológica de una Confederación Aymara. Edición Documental y Ensayos Interpretativos. La Paz: IFEA-Plural, 2006.

Platt, Tristan. Estado Boliviano y Ayllu Andino: Tierra y Tributo en el Norte de Potosí. La Paz, Bolivia: Biblioteca del Bicentenario de Bolivia, 2016

Rivera, Silvia. “Estado Boliviano y Ayllu Andino, 30 Años Después,” 15-34. In Estado Boliviano y Ayllu Andino. Tierra y Tributo en el Norte de Potosí, Tristan Platt, 15-34. La Paz: Bicentennial Library of Bolivia, 2016.

Rasnake, Roger. Autoridad y Poder en los Andes: Los Kuraqkuna de Yura. La Paz: Hisbol, 1989.

Saignes, Thierry. “De la Filiation à la Résidence.” Annales ESC 33, no. 5-6 (1978): 1160-1181.

Wachtel, Nathan. “Los Mitimas del Valle de Cochabamba: la Política de Colonización de Wayna Capac” Historia boliviana I ,1 (1981), 21-57.

Mercedes del Río. “Estrategias Andinas de Supervivencia: El Control de Recursos en Chaqui,” in Espacio, Etnias, Frontera, ed. Ana María Presta (Sucre: ASUR, 1995), 3-47. ↩︎

John Murra. Formaciones Económicas y Políticas del Mundo Andino (Lima: IEP, 1975). ↩︎

Mercedes del Río. “Estrategias Andinas de Supervivencia”, 12-13. ↩︎

Tristan Platt, Thérèse Bouysse-Cassagne and Olivia Harris, Qaraqara-Charka: Mallku, Inka and King in the Province of Charcas (15th - 17th centuries): Anthropological History of an Aymara Confederation (La Paz: IFEA-Plural, 2006). ↩︎

Platt, Bouysse-Cassagne and Harris, Qaraqara-Charka: Mallku, Inka y Rey en la Provincia de Charcas (siglos XV – XVII); del Río. “Estrategias Andinas de Supervivencia”, 8. ↩︎

Roger Rasnake, Authority and Power in the Andes: The Kuraqkuna of Yura (La Paz: Hisbol, 1989); Platt, Bouysse-Cassagne and Harris, Qaraqara-Charka: Mallku, Inka y Rey en la Provincia de Charcas (siglos XV – XVII). ↩︎

Nathan Wachtel. “Los Mitimas del Valle de Cochabamba: la Política de Colonización de Wayna Capac”. Historia Boliviana I, 1 (1981), 21-57. ↩︎

del Rio. “Estrategias Andinas de Supervivencia", 40. ↩︎

Thierry Saignes, “De la Filiation à la Résidence,” Annales ESC 33, no. 5-6 (1978): 1160-1181. ↩︎

del Rio. “Estrategias Andinas de Supervivencia, 39-49. ↩︎

Silvia Rivera. “Estado Boliviano y Ayllu Andino, 30 Años Después,” in Estado Boliviano y Ayllu Andino, Tristan Platt (La Paz: Biblioteca del Bicentenario de Bolivia, 2016), 24-25. ↩︎

Ramiro Ibáñez, “Limitaciones en el Acceso al Sistema de Justicia Boliviano de la Jurisdicción Indígena Originaria Campesina Qhara Qhara Suyu y los Desajustes en la Cooperación y Coordinación”, in Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación, 19, 24 (2021), 87 – 112. ↩︎

Ramiro Ibáñez. Limitaciones en el Acceso al Sistema de Justicia. ↩︎

Samuel Flores Cruz and Stalin Herrera. Caso 110: Las Luchas de los Ayllus Quila Quila Marka. (Movimiento Regional por la Tierra, 2017), 2. ↩︎