Abstract

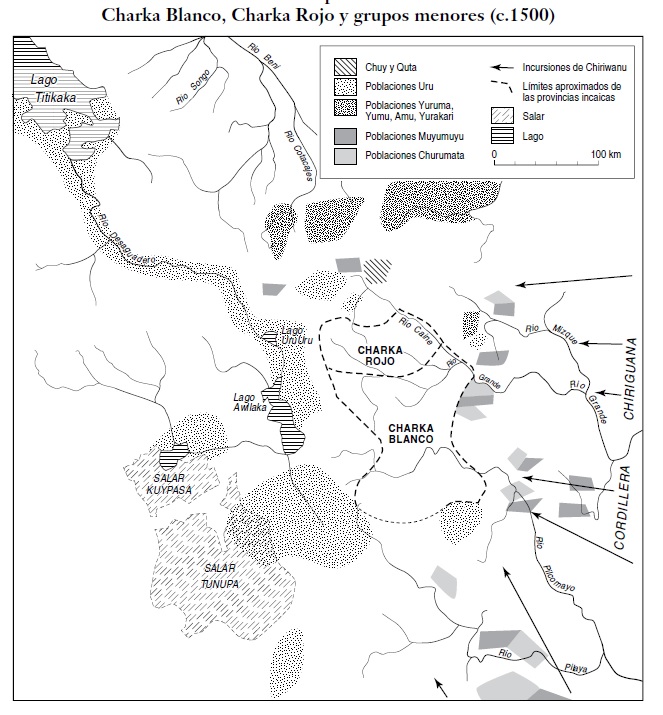

This map focuses on the southeastern region of present-day Bolivia. It displays the location of the territories of the Aymara lordships of the Charka (Red Charka) and the White Charka peoples—which would later become the Qaraqara-Charka federation—, as well as the location of the non-Aymara groups around them, at the end of the 15th century. The map is a snapshot of the time when this region of the Qullasuyu was already part of the Inca state, the Tawantinsuyu, just before the reorganization carried out by Inca Wayna Qhapaq in the first decades of the 16th century. The map also shows the points through which peoples from the low-altitude areas —known as Chiriguanos, nowadays Guaraníes— carried out raids and incursions into the Charka space, originating from the east and the south regions.1

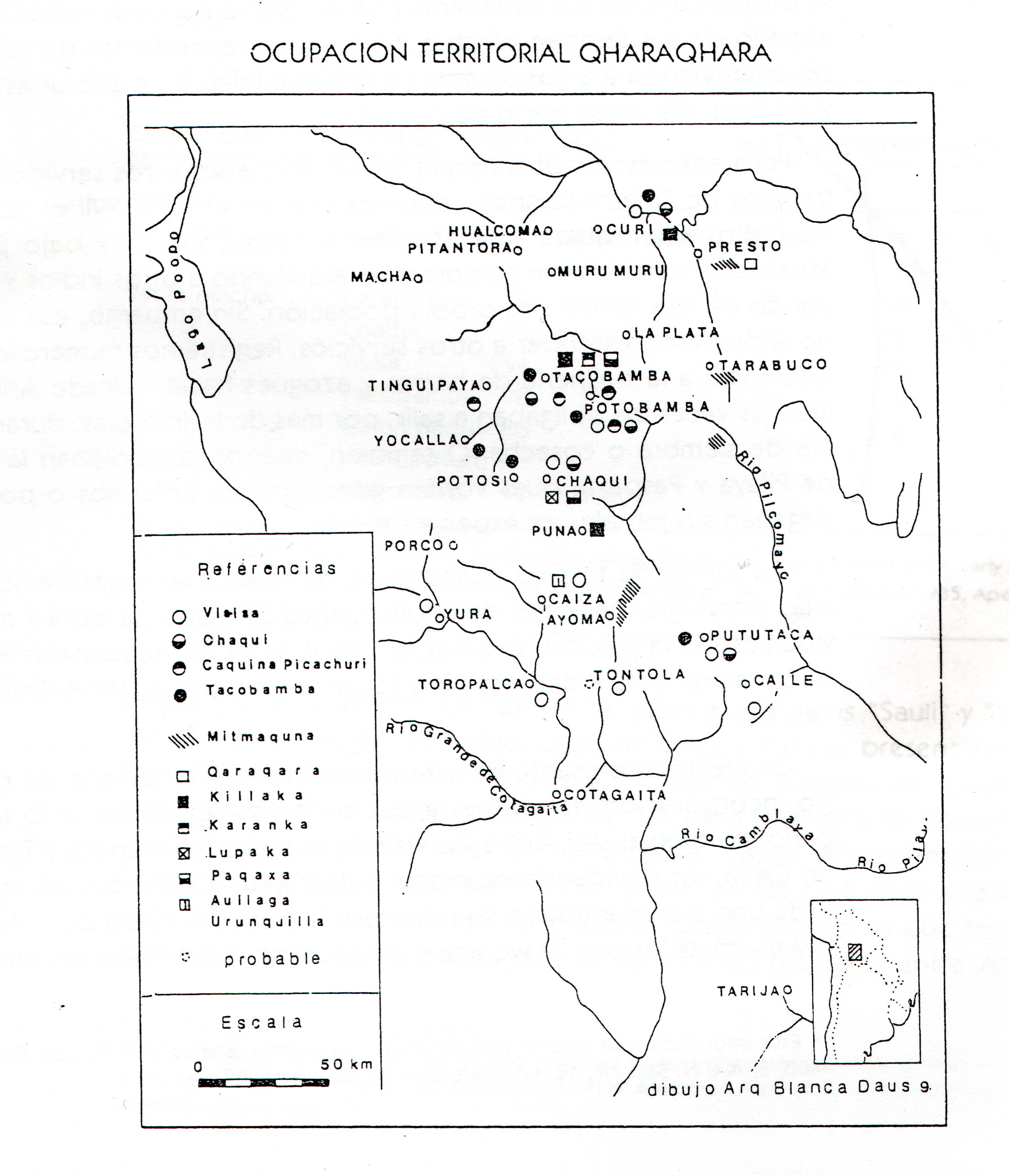

Based on ethnohistoric and anthropological research, the map suggests the mono-ethnicity of the socio-political units of the Charka peoples —also called Charkas and Charcas—, established before the Wayna Qhapaq government. The two major partitions running as an ancient dual Confederation of the Charkas; namely, the White Charkas (Urqu section) and the Red Charkas (Uma section) seem to have split during the government of Wayna Qhapaq. More specifically, the White Charkas constituted the Qaraqaras sociopolitical unit, whereas the Red Charkas became the Charkas separate political entity.2 When the Spaniards arrived in the 1530s, they found two Aymara lordships functioning as a Qaraqara-Charka confederation. This alliance was linked to six other “nations”, south of the Lake Titicaca region known as Collao. Namely, Qaraqara, Sura,Chuy, Killaka, Karanqas, Chichas.

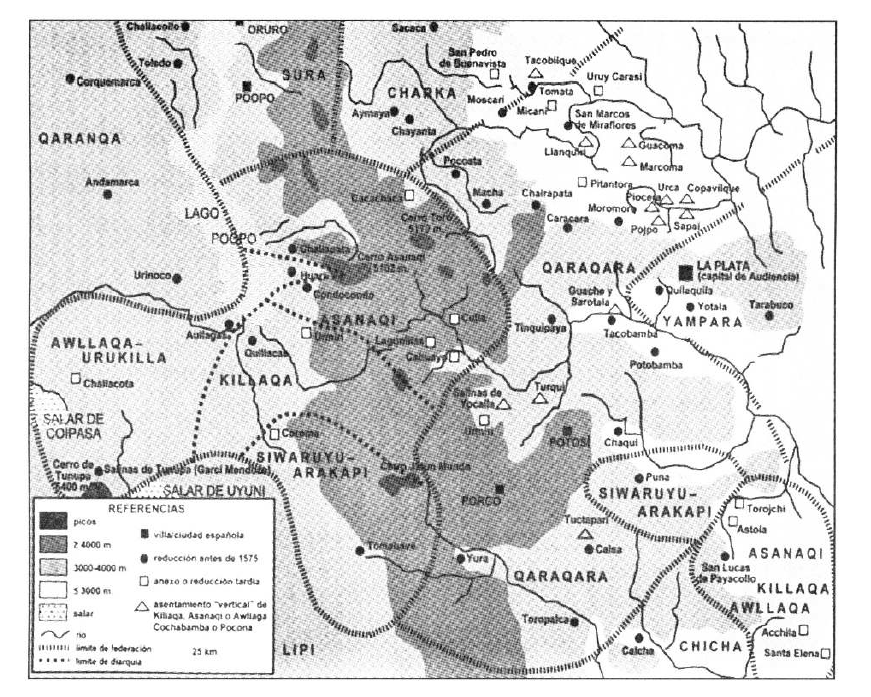

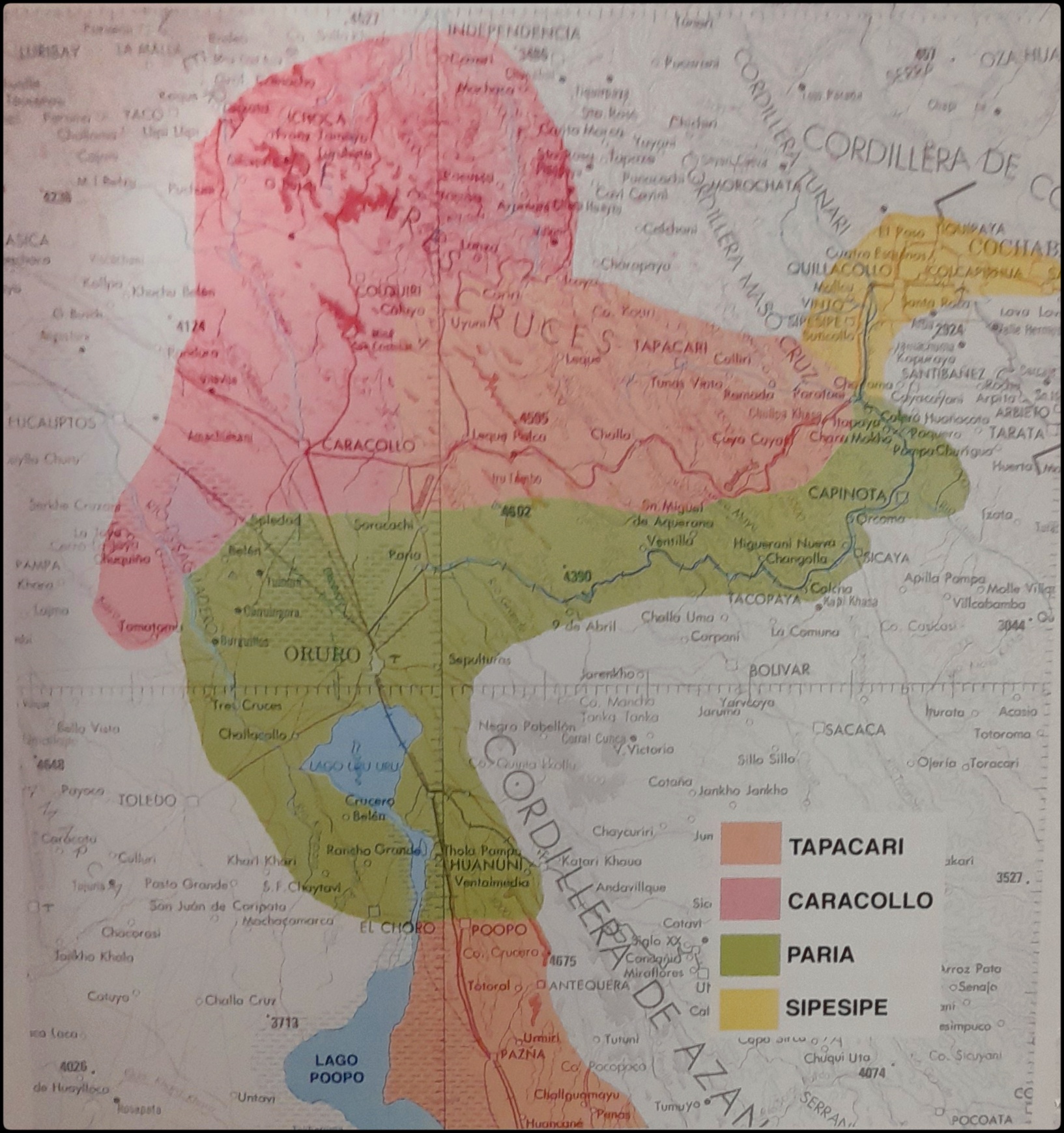

The territorial presence of the Aymara lordship AYMARA POLITIES of THE QULLASUYU in the 16th CENTURY called Charka, a dispersed and non-contiguous territory, was located in the current northwest of the department of Chuquisaca, north of the department of Potosí, center-south and extreme east of the department of Cochabamba.

The colonial territorial-population units (or repartimientos) to which the Charka were assigned around 1550 are the repartimientos of Sacaca, Chayanta —its main centers— and Cochabamba.3 During the early colonial period, the word “Charcas” was extended to all the territories placed under the jurisdiction of the Audiencia de La Plata, the so-called “Audiencia de Charcas,” founded in 1559 with its capital in La Plata. According to its meaning, the word “Charcas” refers to all those “provinces” and “nations” located south of the Collao, and right before reaching the greater Tucumán region, in what is today known as Argentina´s northwest.

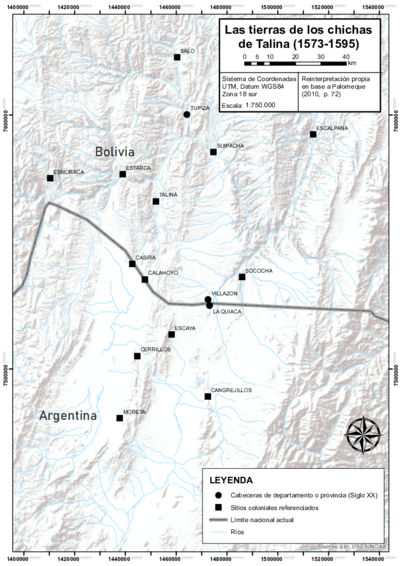

With the new system imposed by the Europeans, the first administrative units around which they tried to organize the region´s Indigenous societies were the repartimientos and the encomiendas. In the corregimiento (province) of Chayanta, —administrative head of the Charka—, the repartimientos respected the system of authorities within the Charkas and Qaraqaras. Thus, the repartimiento of Chayanta —which had more people than Macha and had been previously dispersed in 134 villages—, was resettled in three reduction villages COLONIAL LEGISLATIONS AS FRAMEWORK FOR DISPOSSESSIONS IN THE CENTRAL ANDES: THE “REDUCCIONES” OR “PUEBLOS REALES DE INDIOS” , whereas Macha *—*with a smaller population and previously established in 106 villages—, was resettled in four units.4 The reductions were not implemented on the basis of individuals, but of ayllus, the basic nucleus of family-based territorial organization in the Andes, as part of a population and territorial concentration policy that would breed new collective identities and alterations in the settlements´ hierarchies. The structuring of the territories was adjusted to the features of a population with discontinuous settlement patterns, although these may differ from those in pre-Hispanic times.

The province of Chayanta had five divisions recognized by Viceroy Toledo that maintained their ethnic affiliation. The ayllus had to coexist within the colonial towns, especially in the valley zone where the “archipelago” formation was heightened. Even so, ethnic identities were maintained by assigning “streets” to each ayllu, which served as territorial borders or boundary markers.5

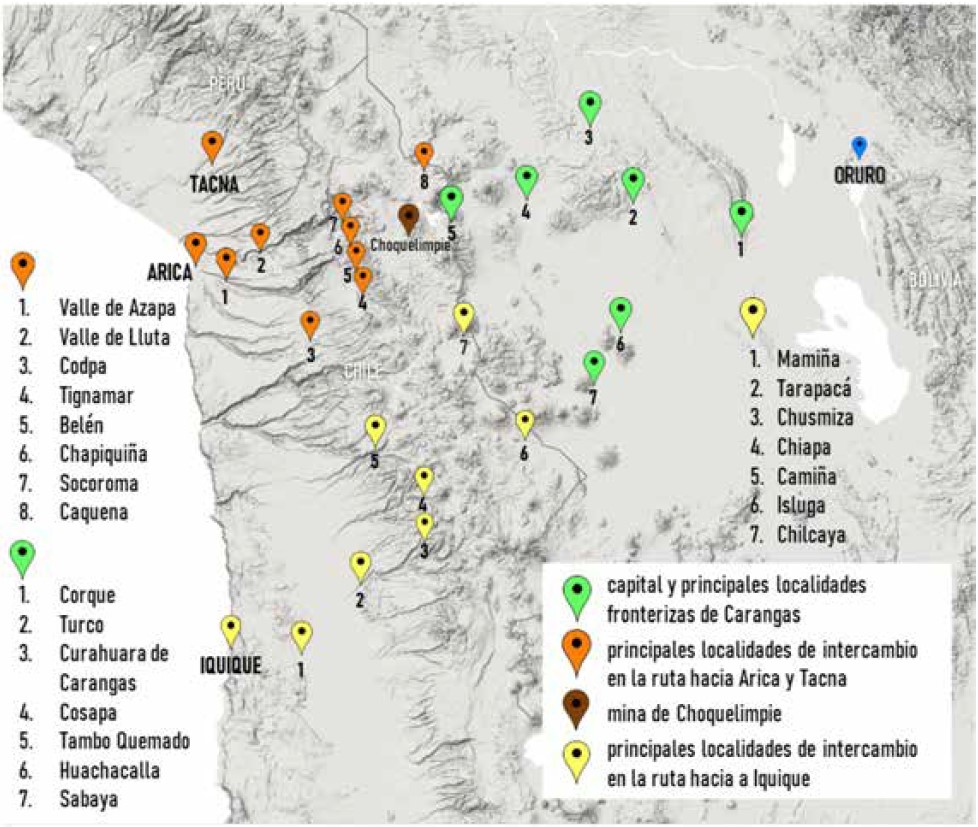

In the period between the foundation of the Republic, in 1825, and the years prior to the Pacific War (1879-1883), land control in the altiplano and valley regions allowed family subsistence to be minimally secured within the same province, and served in turn as a basis for the creation of marketable surpluses on community lands. The administration of the production and commercialization of wheat and corn was left to the ayllus´ Indigenous authorities, who were able to generate surpluses to comply with their payment obligations of the Indigenous tribute COLONIAL LEGISLATION AS FRAMEWORK FOR DISPOSSESSIONS IN THE CENTRAL ANDES: THE INDIGENOUS TRIBUTE, 1730s - 1820s still in force and perceived by the ayllus as a “reciprocity pact” that guaranteed their safe access to the lands.6 However, the republican state preferred to emphasize that the ayllus were simple beneficiaries of the state lands and that the tribute was a simple lease paid to the state as the sole owner of all lands.7 As a consequence, customs barriers were removed, and the state monopoly on the purchase of silver paste was annulled. In turn, the railroad directed its railway lines towards export points to the detriment of inner road integration, which resulted in a domestic market crisis. This liberal program had its repercussions in the wheat production crisis in the Charka region, and in the second boom of silver mining for export in Colquechaca. During the 19th century, the mestizos and the regional Creole elites once again monopolized the position as tribute collectors for the ayllus and subdivisions in the region until the Federal War of 1899.

The application of liberal policies left open a legal pathway that would “justify” the forced selling of land imposed on communities in some regions. The Land Alienation Laws imposed from the 1870s onwards gave rise to a “paternal generosity” stance by seeking the expiration of ayllu as collective property in favor of individual tenure and private property, considered a sign of “modernity and progress.” These laws, which in many areas generated the conversion of the communal Indian into colonist, tenant farmer and small landowner, did not have the same effect on the ayllus that belonged to the Qaraqara-Charka confederation. In Charka, they continued to have possession over their territories with their main centers in the altiplano and their “islands” in the valleys, in line with the system of vertical control of the ecological niches. Faced with the threat of expropriation of their own lands, the mestizo neighbors of the towns allied with the ayllus, and the hacienda owners failed to obtain the power they yielded in La Paz.

On their part, the authorities of Potosí and its provinces did not agree with a tax reform that would take away the main income in the departmental coffers in exchange for an uncertain “cadastral tax”, stipulated in the Land Alienation Act of 1874, which even the landowners were unwilling to pay.8 In order to pay the tax, a periodic readjustment of the amount budgeted for each province was required. It was necessary to carry out “revisitas”, where the names of the taxpayers and their families were recorded, as well as details of the land they occupied and the tax category to which they belonged. This generated a sort of “fiscal lawlessness” by which the government authorities tried to expand their income sources at the expense of the traditional jurisdiction of the Indigenous authorities.9

One of the effects of the Land Reform of 1953 was the legalization of land on an individual basis, since the Law did not recognize collective tenure, which led to a process of unionization of peasant organizations. However, the ayllus, with records and documentation from colonial times, maintained their collective lands and based on this form of organization, sought to legalize their territory according to the available legislation. The case of the ayllu Chayantaka, in the municipality of Chayanta, former head of Charka, is paradigmatic of the situation of the Charka ayllus today. Chayantaka demanded the endowment and “recovery” of dispersed and discontinuous territories in their ancestral ecological valley niche, but the loss of real ties and the gradual fragmentation processes that ensued since 1570 led to the abdication of this territory, which remains in the ancient memory of the original Chayantaka inhabitants, since there is still a cultural identity bond with this region. Thus, it was not possible to consolidate the discontinuous territoriality, an Andean original trait that the colonial and republican state managed to dispossess.

REFERENCES:

Adrián, Mónica. “Acerca de las unidades de análisis en el sur andino colonial a partir

de un estudio de caso: Chayanta, siglo XVI– siglo XVIII”. Surandino Monográfico, 2-2 (2012), 1-31.

Calizaya Velásquez, Oscar. “Estudio de Caso Nº 1. Chayantaka, el Ayllu con Gestión Territorial Indigena: Territorio Originario en Potosí”. En Territorios Indígena Originario Campesinos en Bolivia: Entre la Loma Santa y la Pachamama. Informe 2010, edited by Fundación Tierra, 233- 263. La Paz: Fundación Tierra, 2011.

Platt, Tristan, Thérèse Bouysse-Cassagne, and Olivia Harris. Qaraqara-Charka: Mallku, Inka y Rey en la Provincia de Charcas (siglos XV - XVII): Historia Antropológica de una Confederación Aymara (Qaraqara-Charka: Mallku, Inka y Rey en la Provincia de Charcas (siglos XV - XVII): Historia Antropológica de una Confederación Aymara). La Paz: Plural-IFEA, 2006.

Platt, Tristan Estado Boliviano y Ayllu Andino: Tierra y Tributo en el Norte de Potosí (2nd ed.). La Paz, Bolivia: Biblioteca del Bicentenario de Bolivia, 2016.

Rivera, Silvia. “Estado Boliviano y Ayllu Andino, 30 Años Después” [Introductory Study], 15-34. In Estado Boliviano y Ayllu Andino. Tierra y Tributo en el Norte de Potosí, Tristan Platt, 15-34. La Paz: Bicentennial Library of Bolivia, 2016.

Tristan Platt, Thérèse Bouysse-Cassagne and Olivia Harris. Qaraqara-Charka: Mallku, Inka y Rey en la Provincia de Charcas (siglos XV - XVII): Historia Antropológica de una Confederación Aymara (La Paz: Plural-IFEA, 2006), 57. ↩︎

Platt, Bouysse-Cassagne and Harris*. Qaraqara-Charka,* 46. ↩︎

Mónica Adrián, “Acerca de las Unidades de Análisis en el Sur Andino Colonial a partir de un Estudio de Caso: Chayanta, Siglo XVI- Siglo XVIII”. Surandino Monográfico, 2-2 (2012): 1-31. ↩︎

Adrián, “Acerca de las Unidades de Análisis en el Sur Andino Colonial a partir de un Estudio de Caso”. ↩︎

Platt, Bouysse-Cassagne and Harris. Qaraqara-Charka: Mallku, Inka and King in the Province of Charcas (15th - 17th centuries), 71. ↩︎

Tristan Platt, Estado Boliviano y Ayllu Andino: Tierra y Tributo en el Norte de Potosí (2nd ed.) (La Paz: Biblioteca del Bicentenario de Bolivia, 2016). ↩︎

Platt. Estado Boliviano y Ayllu Andino: Tierra y Tributo en el Norte de Potosí ↩︎

Silvia Rivera, “Estado Boliviano y Ayllu Andino, 30 Años Después” [Introductory Study], 15-34. In Bolivian State and Andean Ayllu. Land and Tribute in Northern Potosí, Tristan Platt, 15-34. (La Paz: Bicentennial Library of Bolivia), 2016. ↩︎

Platt, Estado Boliviano y Ayllu Andino. Tierra y Tributo en el Norte de Potosí. ↩︎