Abstract

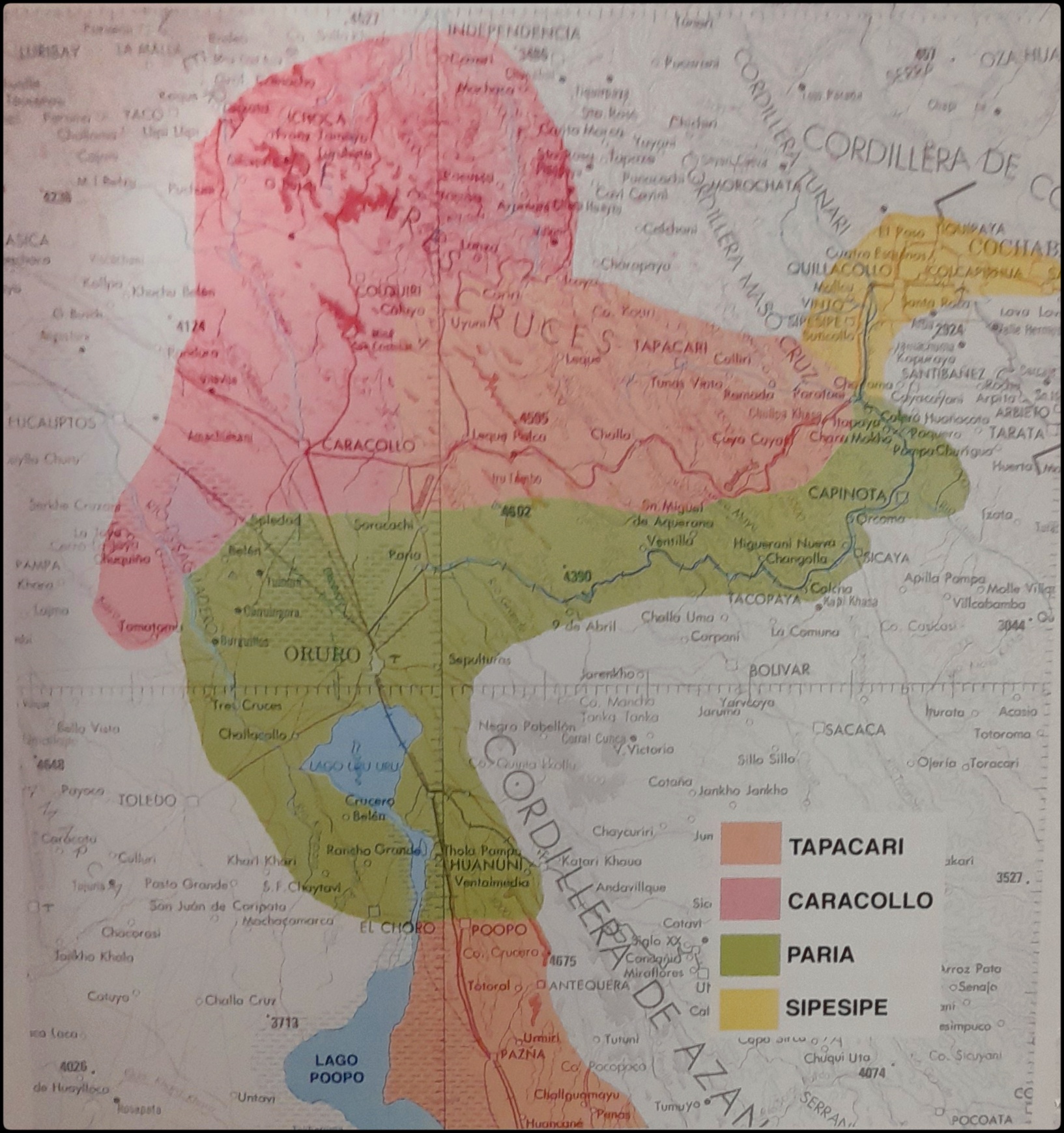

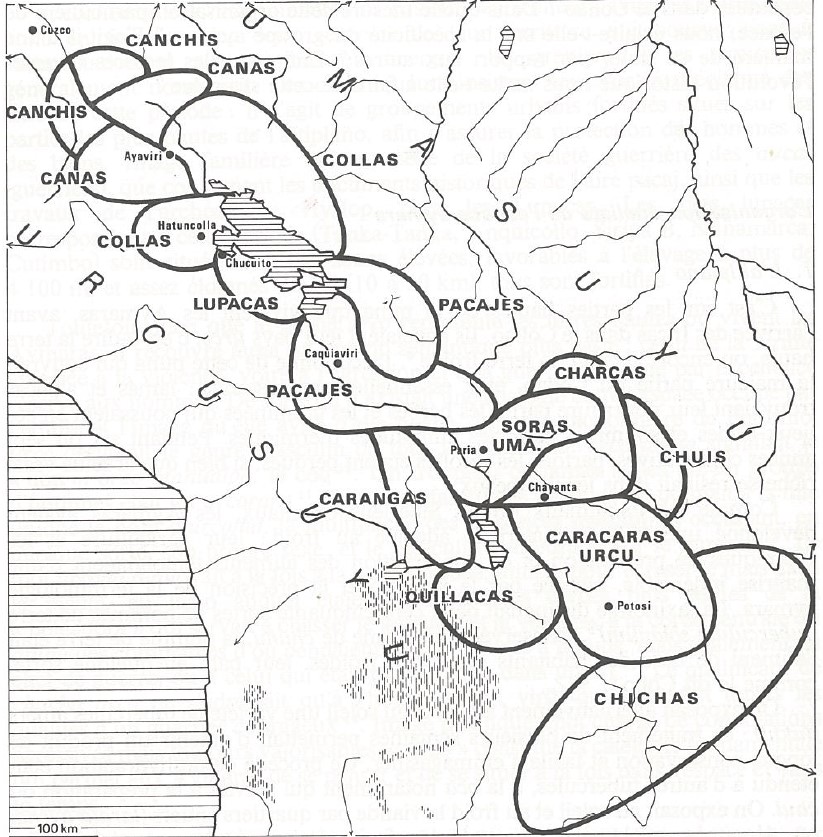

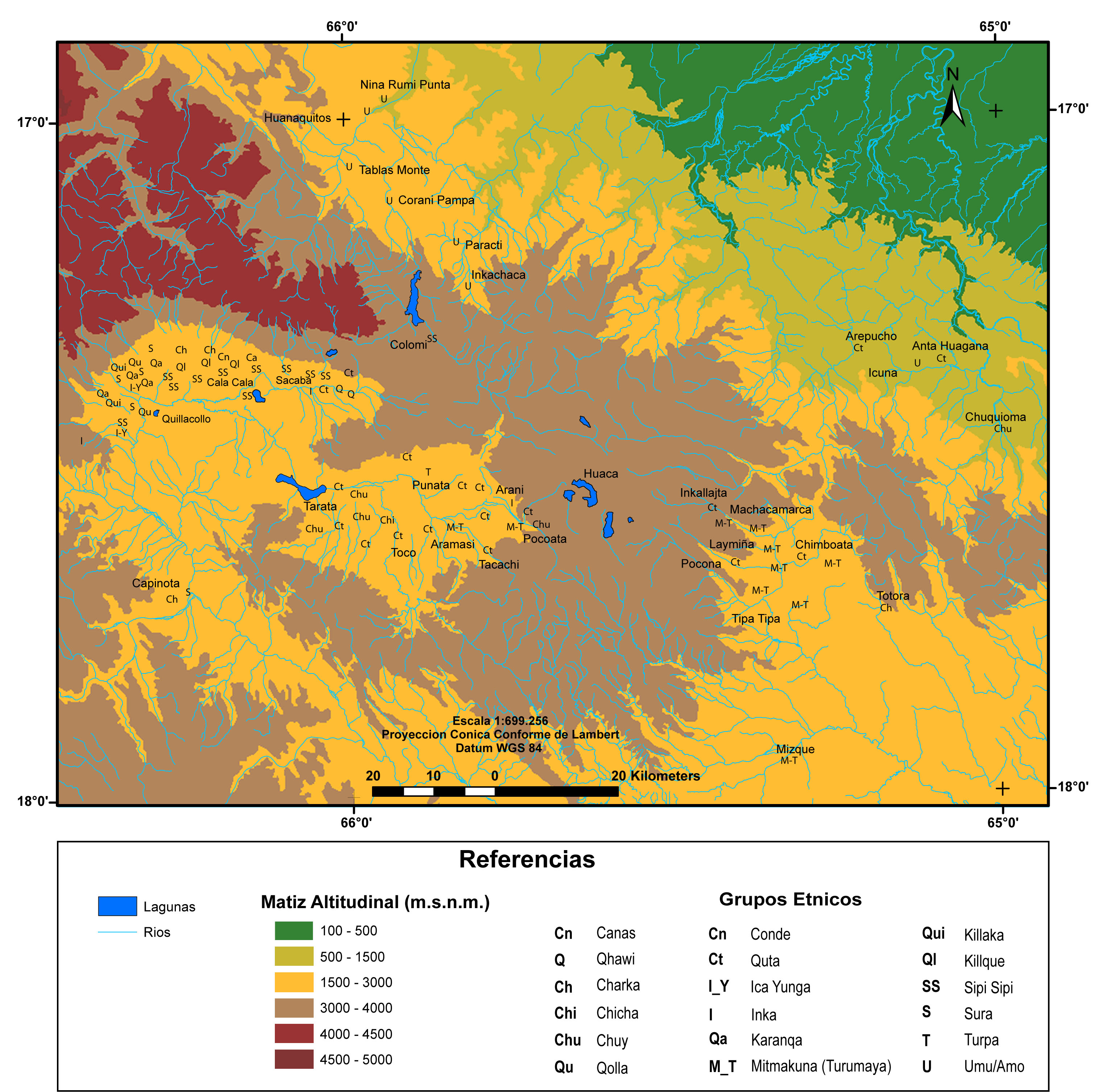

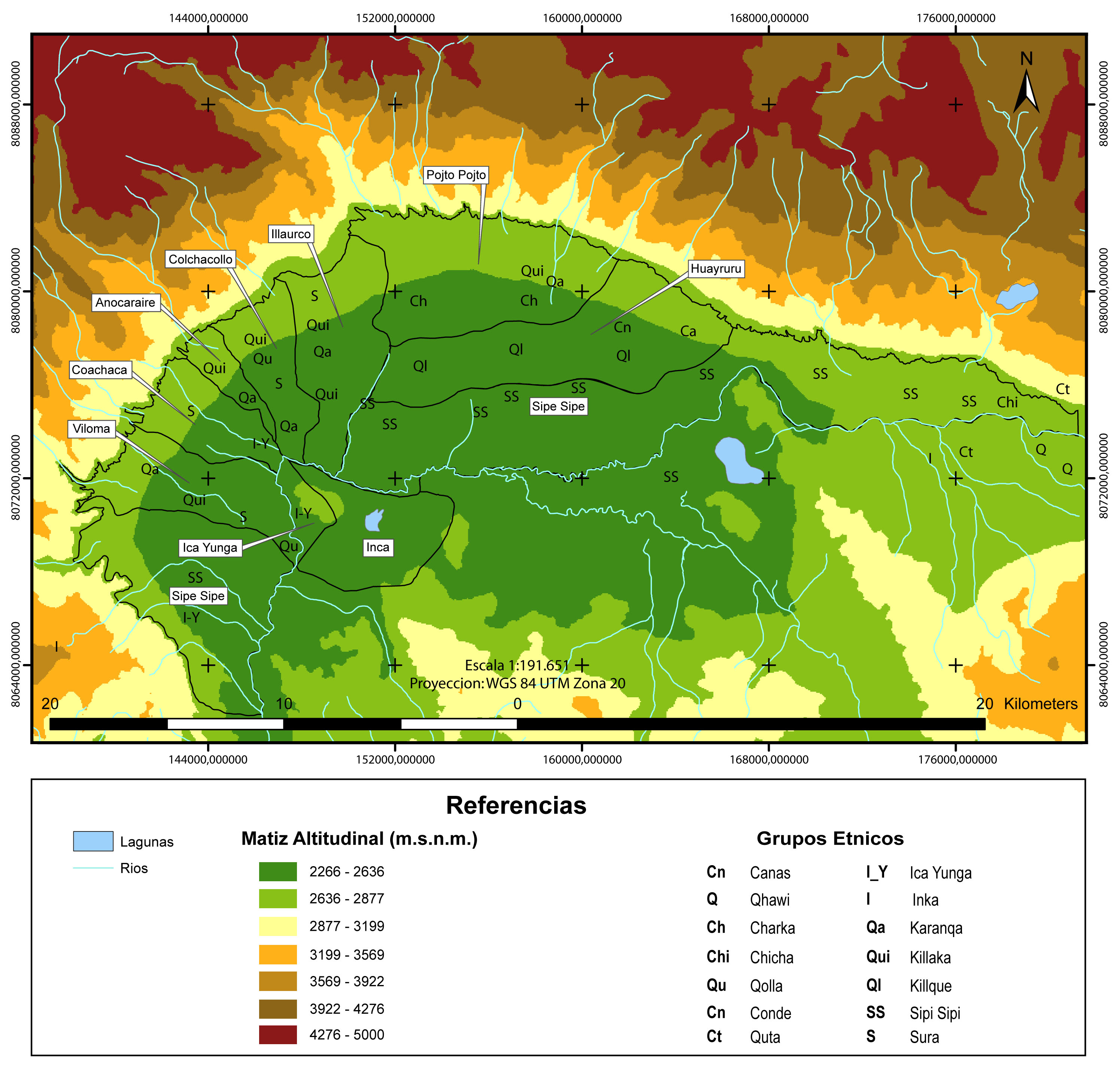

The map displays the four Aymara polities AYMARA POLITIES of THE QULLASUYU in the 16th CENTURY that formed the Sura Federation —or Sora, Sulla, Zora, Çora or Çoraçora, depending on the source consulted—: the Sura of Paria, Tapacarí, Caracollo and Sipe Sipe in the Qullasuyu territory THE QULLASUYU IN THE 1530s – SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF THE INCA STATE , southern district of the Inca state or Tawantinsuyu.1 Each had its own territory (with a subdivision into two upper and lower halves). Before the 16th century, these four political entities could have been integrated as one or as a diarchy with two main sections, Paria as the upper half and Tapacari as the lower half. However, there is no historical evidence to support either hypothesis.2 The Sura territories included a large area of the eastern center of the altiplano —currently the department of Oruro—, and extended eastward through the Tapacari and Arque river valleys —in the department of Cochabamba. Following the model of vertical control of ecological niches and territorial discontinuity, the central settlements were in the altiplano, and the various ethnic “islands” stood along the inter-Andean valleys.

The case of the Sura, however, presents slight adaptations in relation to this general model of the Aymara lordships AYMARA POLITIES of THE QULLASUYU in the 16th CENTURY . These variations could have been the result of Inca territorial reorganization policies. The Sura territory of Sipe Sipe was entirely situated in the valleys. However, the Sura central settlement of Tapacarí was not located in the altiplano, but in the middle of the Tapacarí river valley. It is also worth noting that the altiplano settlements of the Sura population from Tapacarí were at a greater distance and more clearly spread out from their valley settlements than in the other cases.3

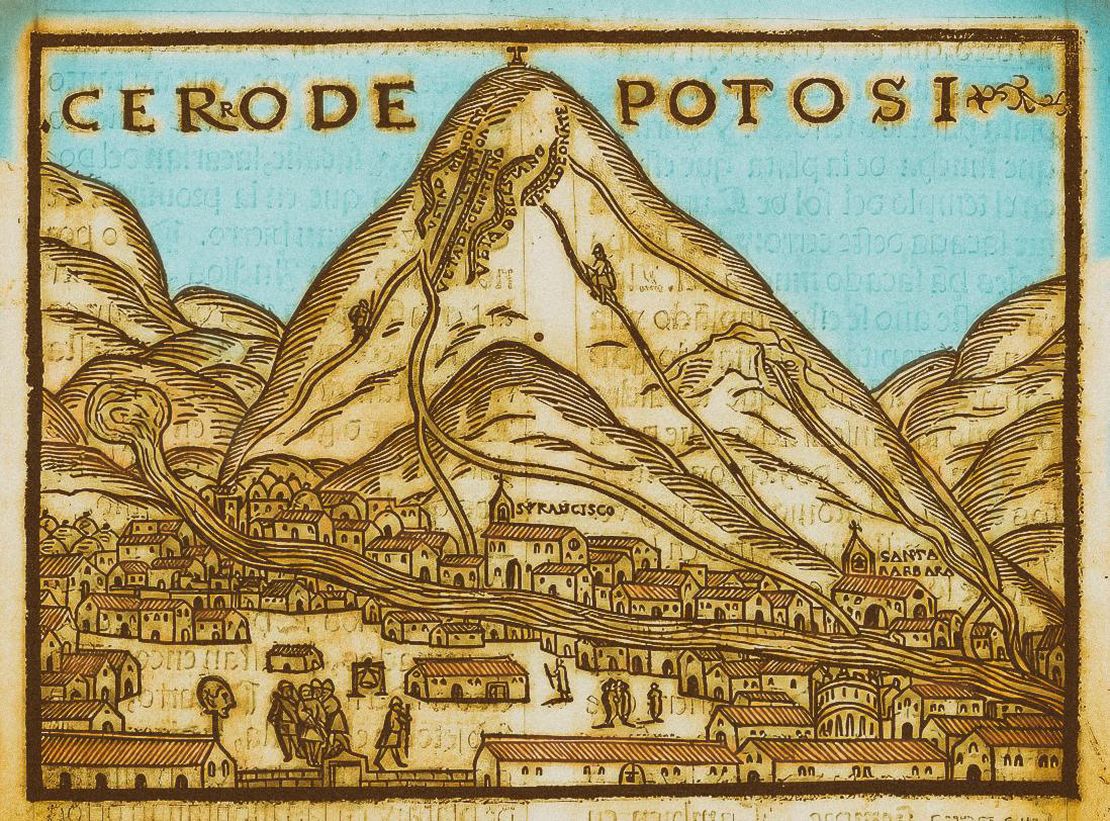

Since the Sura territories extended eastward along the Tapacarí and Arque river valleys, both in Inca and colonial times, these valleys formed a “natural corridor” connecting the multi-ethnic MULTI-ETHNIC TERRITORY under INCA DIRECT RULE: THE CENTRAL AND UPPER VALLEYS OF COCHABAMBA in the 1530s territory MULTI-ETHNIC TERRITORY under INCA DIRECT RULE: THE LOWER VALLEY OF COCHABAMBA in the 1530s of the Cochabamba valleys with the altiplano. Under the Inca rule, maize produced in the Inca state lands was transported by llamas to Cuzco. Under Spanish colonial rule, agricultural products from the valley-based haciendas were taken to the markets of the silver mines of Potosí.

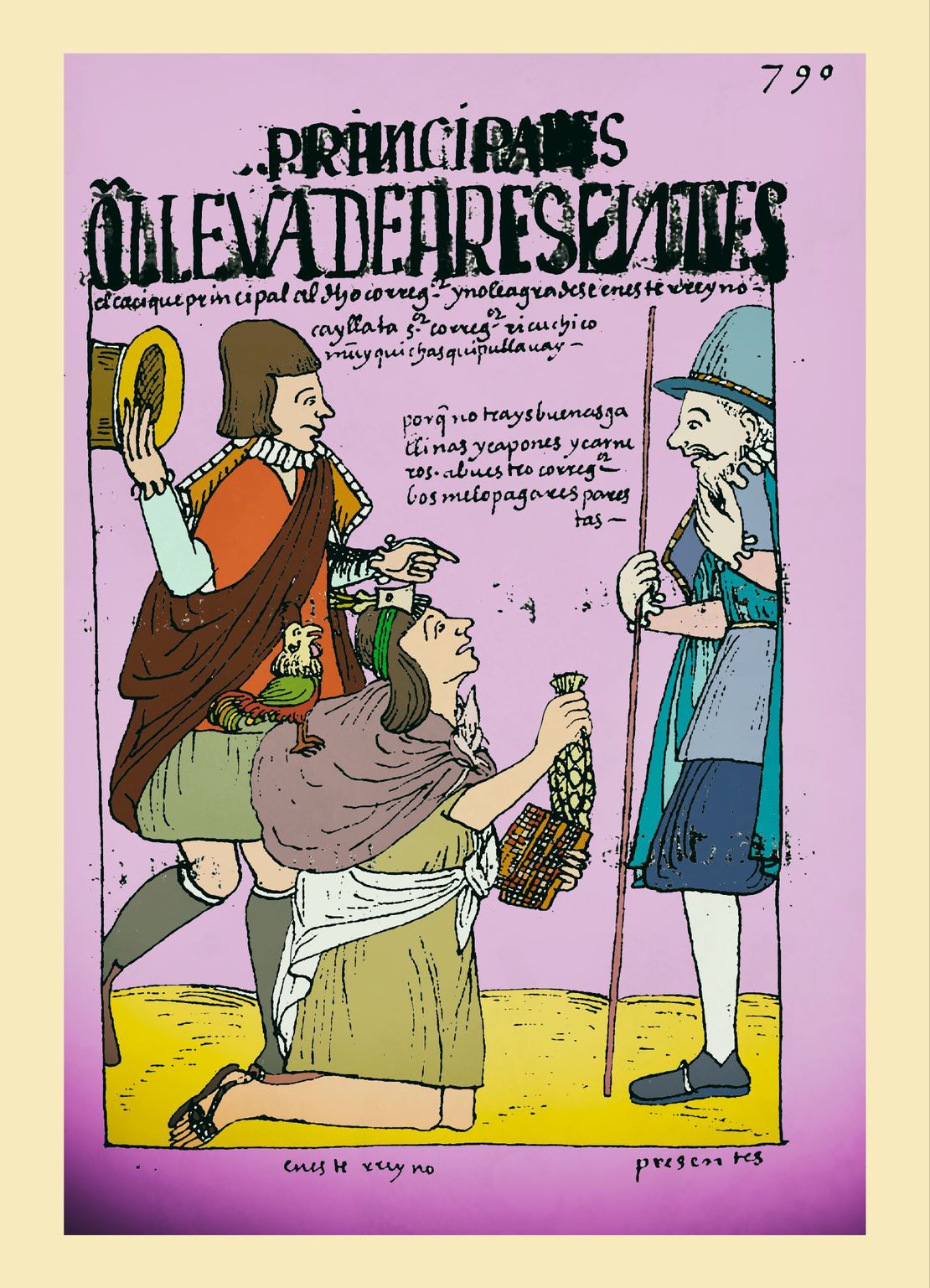

In no time, the Sura were impacted by the new colonial regime that had undergone drastic changes, especially in terms of their territorial patterns. The first encomienda system covered the population in “the Soras province”, as the important administrative center of Paria turned into a military base for Spanish soldiers. The territorial center of Suras in Paria moved to the valleys of Cochabamba. By the late 1540s, the Indigenous population of the Sura territories had been “distributed” into four repartimientos —colonial territorial-population unit— and assigned to four different encomenderos under the encomienda labor system. Although this allowed the Sura peoples to maintain and extend their original groups during the colonial period, these new repartimientos disrupted the federation´s structure, considered as the maximum level of intersection among the numerous centers.4 This new colonial scheme added to the fact that Paria, their main administrative center, had been relocated, marked the beginning of a new fragmentation process of the Sura macro-ethnic federation. Moreover, the establishment of these four repartimientos had not considered the existence of the Sura colonies or ethnic “islands” that had been relocated by the Inca state to places far from the main Sura territories. This meant that “the Sura who had been [relocated by the Incas], had been also separated from their groups of origin and integrated into different encomienda labor systems.” 5 There is no doubt that the repartimiento and encomienda —as colonial forms of population organization for the extraction and collection of surplus and labor recruitment— represented a threat and a heavy burden for the Sura polities. However, since their territorial and social organization as well as their forms of production had remained relatively unaffected, the Sura were able to withstand the burden and pressures without significantly undermining their self-sufficiency capabilities.

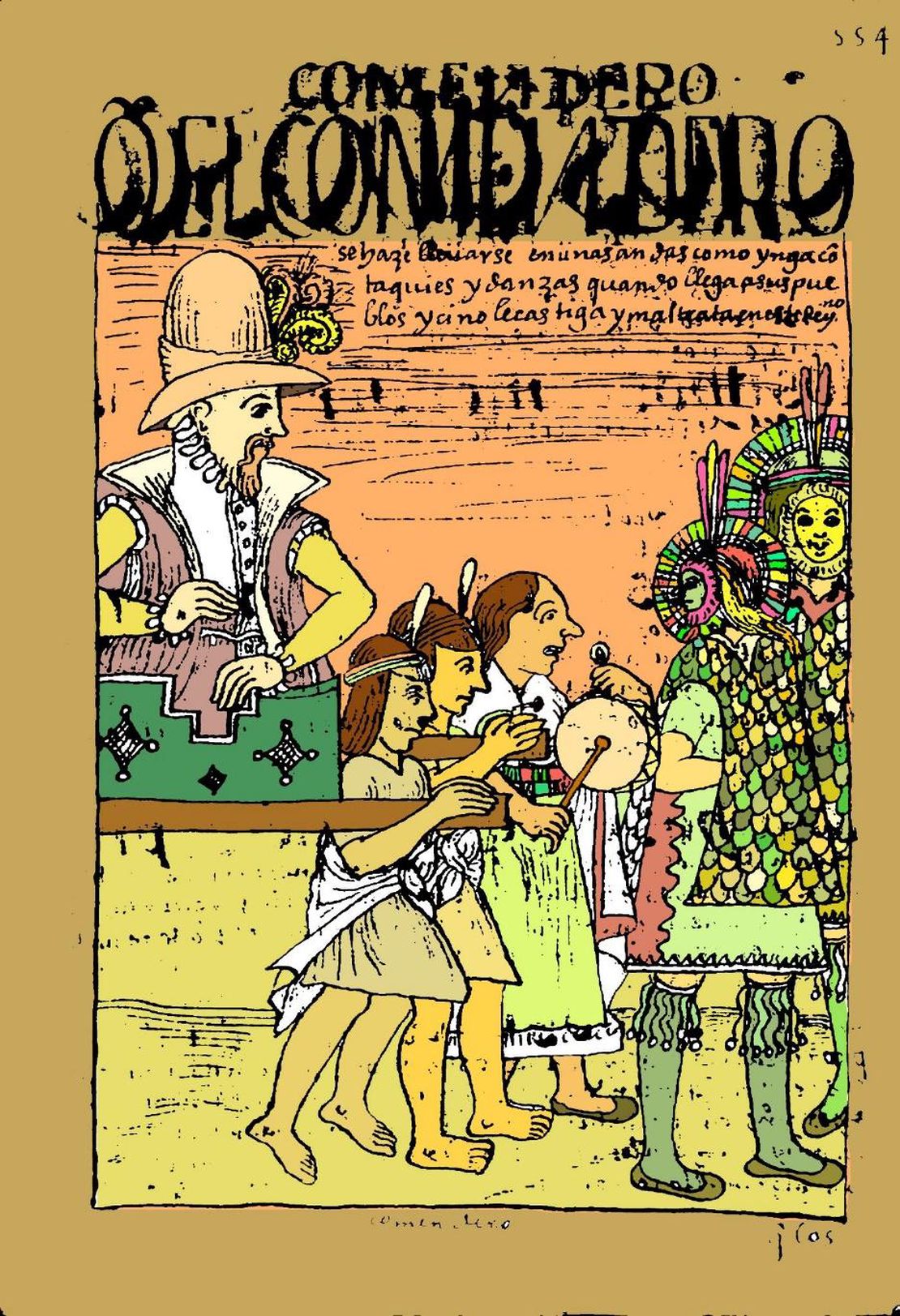

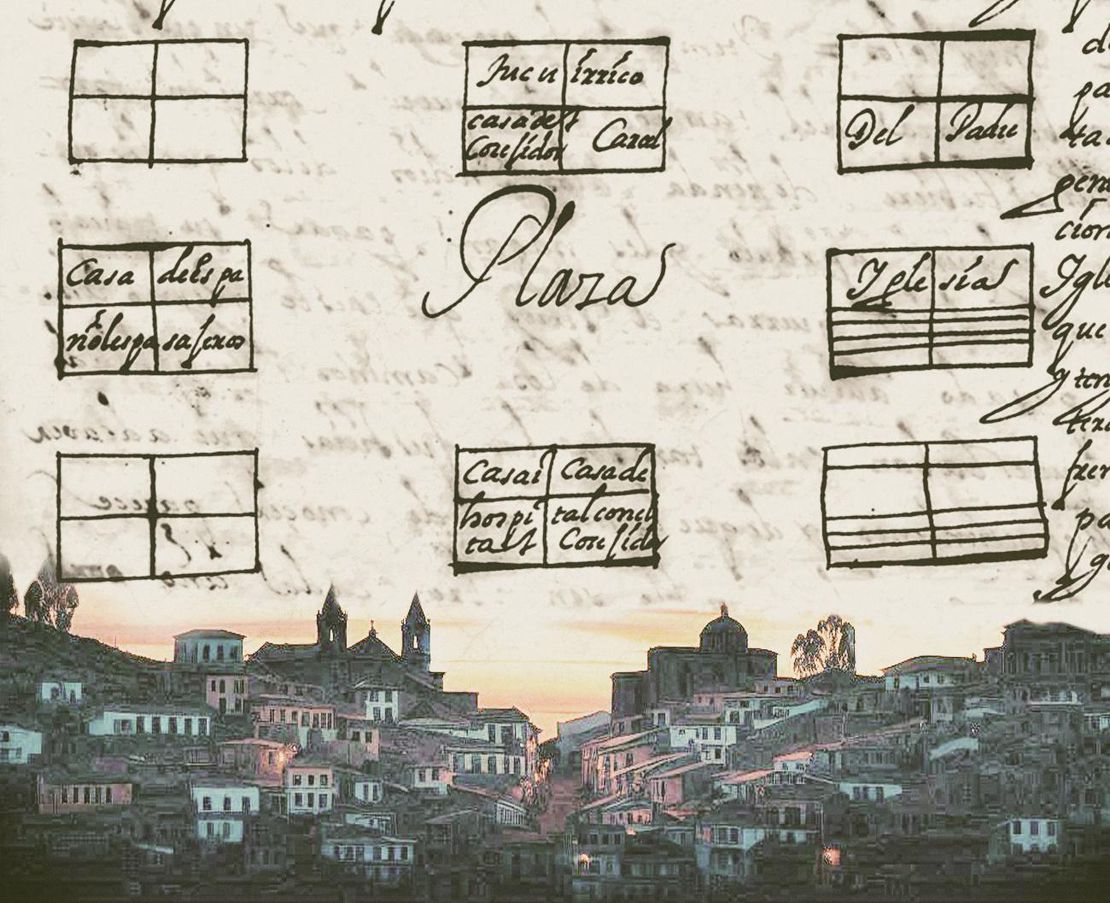

Greater and even more radical transformations occurred in the context of the major reforms implemented in the 1570s by Viceroy Toledo to consolidate and institutionalize the presence of the colonial state, and increase silver production in the Potosí mines. The three reforms that most affected the Aymara lordships, in general, and the Sura, in particular, were the following: 1) the forced resettlement of scattered villages and their concentration or “reduction” into central towns called “Pueblos Reales de Indios” COLONIAL LEGISLATIONS AS FRAMEWORK FOR DISPOSSESSIONS IN THE CENTRAL ANDES: THE “REDUCCIONES” OR “PUEBLOS REALES DE INDIOS” ; 2) the rationalization, individualization and monetization of the Indigenous tribute COLONIAL LEGISLATION AS THE FRAMEWORK FOR DISPOSSESSIONS IN THE CENTRAL ANDES: THE INDIGENOUS TRIBUTE 1570s -1620s ; and 3) the mandatory recruitment of Indigenous labor for the mines of Potosí known as the mita system COLONIAL LEGISLATIONS AS A FRAMEWORK FOR DISPOSSESSIONS IN THE CENTRAL ANDES: THE COLONIAL MITA . Conceived as a rationalization of the colonial administration of territories and populations, and as a systematization of the mechanisms of surplus extraction, collection, and labor, these three reforms were closely articulated. The reducciones played a key role in this arrangement. Indeed, the reducciones made it possible to govern the “Indians” and evangelize them in a more orderly manner, collect tribute more systematically, and recruit workers on duty for the mita labor system more efficiently.

The “reduction of Indians” implied the disruption of the Sura people’s territorial organization, the uprooting of hundreds of villages scattered throughout the valleys, and the rearrangement of their kinship networks and ethnic identities, as the forced resettlements were rather arbitrary and ended up concentrating families with different ethnic affiliations in the same pueblo real de indios. Although groups were organized within each village following and maintaining elements of the ayllu structure, these were groups with a new configuration, something like reshuffled ayllus that in time became the main reference for the development of new ethnic identities on a much smaller scale than the macro-polis the Sura had reached. In terms of tax reforms, the monetization of the Indigenous tribute led to a greater integration of the Sura into the market. The way for the Sura people to earn the money to meet their tribute obligations was through selling what they had produced, more specifically their woven clothing items and garments.6 The mita obligations in the Paria repartimiento involved working in the mines of Potosí, working in other mines, performing agricultural work in the Spanish haciendas, conducting domestic work in convents and hospitals, and carrying out postal and transport services, all of which presented a very heavy burden, particularly in the context of the demographic decline that characterized the 17th century.

By the end of the colonial period and the beginning of the 19th century, the great federation of four Sura polities had been completely dismantled. The strong connections between the highlands and the valleys that had characterized the territories of three of the four Sura confederations had been deeply severed, destroying the pattern of macro-vertical control of the ecological niches with significant and profound implications in terms of dispossessions. At this point, the Sura name and even more the memory of having belonged to a large Sura polity had completely vanished. The four Sura polities had shattered into a multiplicity of reorganized ayllus or into the so-called “Indian communities” —term acquired during the colony.

While in the altiplano region the Sura descendants managed to maintain collective ownership of the land as reorganized ayllus or Aymara-speaking Indigenous communities, the consolidation of private property in the valleys turned many of them into Quechua-speaking peasants subject to the hacienda servile structures. This situation —long-lasting and especially exacerbated after the creation of the Republic of Bolivia—, changed with the Agrarian Reform of 1953 when the lands of the large haciendas were redistributed as individual private properties to the Indigenous people organized in agrarian unions commonly called sindicatos de campesinos (peasant unions). In this new context, some Indigenous communities of the altiplano remained as ayllus with collective land ownership, whereas others processed individual land titles and organized themselves as peasant unions.

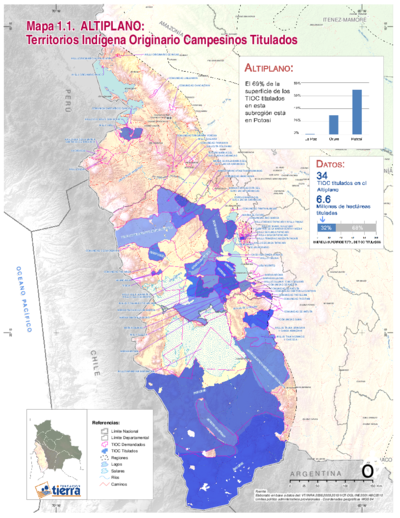

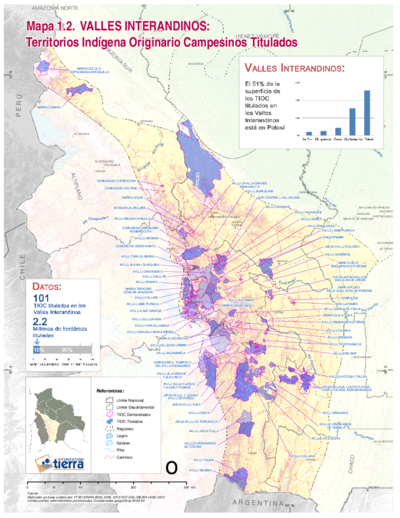

In the context of the current Plurinational State of Bolivia and the 2009 Constitution recognizing the legal classification of “Territorios Indígenas Originarios Campesinos” TITLED INDIGENOUS TERRITORIES (TIOC) IN THE BOLIVIAN ALTIPLANO AS OF 2011 or TIOCS, there has been a renewed interest by many Indigenous communities of the altiplano and some peasant unions of the valleys to organize themselves as ayllus and demand the titling of their lands as TIOCS. However, these demands have been made by independent ayllus and do not necessarily have the goal of reconstructing the territories as part of the Sura macro-polity. There are currently 17 recognized Indigenous territories in the grounds of what used to be the great Aymara lordships of the Sura Federation in the 16th century.7 Ten of these territories are in the highlands of Oruro department while the other seven are in the Cochabamba department. The Oruro territories represent almost 360,000 hectares while those of Cochabamba amount to 935,000 hectares. An estimated total of 105,000 people live in these territories.8 Are these Indigenous peoples, mostly Qhishwa-speaking —except for the inhabitants in the highland Tapacari and Paria parts—, descendants of the Sura of Paria and Tapacari polities that had controlled the territories of what are now the provinces of Arque and Tapacari respectively in the 16th century? Some of them could be, others could be descendants of the “outsiders” who migrated to these regions from other Aymara polities during the colonial period. At the beginning of the 21st century and up to the present day, their identities have been defined mainly by their belonging to a specific Indigenous/peasant community of origin, on the one hand, and to a strong peasant union structure on the other. The memories of belonging to a larger unit or even of the name Sura have been lost in the historical process.

REFERENCES:

del Río, Mercedes. Etnicidad, Territorialidad y Colonialismo En los Andes: Tradición y Cambio entre los Soras de los Siglos XVI y XVII (Bolivia). La Paz: Instituto de Estudios Bolivianos, 2005.

Fundación Tierra. Territorios Indígena Originario Campesinos en Bolivia. Entre la Loma Santa y la Pachamama. Informe 2011. La Paz: Fundación Tierra, 2011.

Schramm, Robert. “Fronteras y Territorialidad: Repartición Étnica y Política Colonizadora en los Charcas (Valles de Ayopaya y Mizque).” In Espacio, Etnias, Frontera: Atenuaciones Políticas en el Sur del Tawantinsuyu Siglos XV - XVIII, compiled by Ana María Presta, 163-188. Sucre, Bolivia: ASUR, 1995

Mercedes del Río, Etnicidad, Territorialidad y Colonialismo en los Andes: Tradición y Cambio entre los Soras de los Siglos XVI y XVII (Bolivia) (La Paz: Instituto de Estudios Bolivianos, 2005). ↩︎

del Río, Etnicidad, Territorialidad y Colonialismo en los Andes: Tradición y Cambio entre los Soras de los Siglos XVI y XVII (Bolivia); Robert Schramm, “Fronteras y Territorialidad: Repartición Étnica y Política Colonizadora en los Charcas (Valles de Ayopaya y Mizque),” in Espacio, Etnias, Frontera: Atenuaciones Políticas en el Sur del Tawantinsuyu Siglos XV - XVIII, ed. Ana María Presta (Sucre: ASUR, 1995), 163-188. ↩︎

del Río. Etnicidad, Territorialidad y Colonialismo en los Andes. ↩︎

del Río. Etnicidad, Territorialidad y Colonialismo En Los Andes, 283. ↩︎

del Río. Etnicidad, Territorialidad y Colonialismo En Los Andes, 105. ↩︎

del Río. Etnicidad, Territorialidad y Colonialismo En Los Andes. ↩︎

Fundación Tierra, Territorios Indígena Originario Campesinos en Bolivia. Entre la Loma Santa y la Pachamama, Informe 2011, (La Paz: Fundación Tierra, 2011). ↩︎

Fundación Tierra, Territorios Indígena Originario Campesinos en Bolivia. Entre la Loma Santa y la Pachamama, Report 2011. ↩︎