Abstract

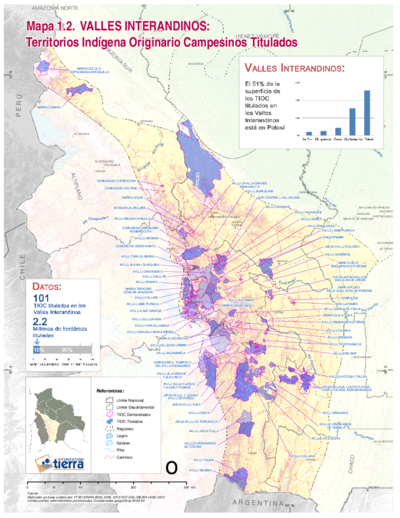

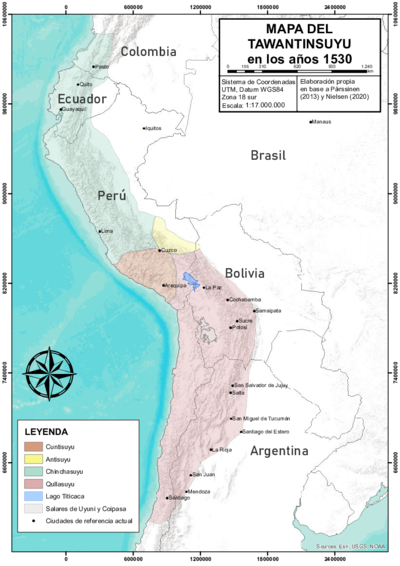

Focusing on the altiplano or high plateau region, which in pre-colonial times was part of the Qullasuyu, i.e., the southern district of the Inca state or Tawantinsuyu, the map shows the Indigenous territories that were officially recognized by the Plurinational State of Bolivia in 2011. Indigenous peoples living in specifically designated territorial units had received property titles granting them the right to collective ownership of those territories in which they had the right to apply their own forms of economic, political, social, and cultural organization, as well as the right to the use and management of all renewable resources. As per the 2009 Bolivian Constitution, this collective property would be inalienable, indivisible, irreversible, unseizable, and imprescriptible1

The official name of the Indigenous Territories according to the current legislation of the Plurinational State of Bolivia is “Territorios Indígenas Originarios Campesinos” (TIOCs) MAP OF TITLED INDIGENOUS TERRITORIES (TIOC) IN BOLIVIA, AS OF 2011 . This term is intended to recognize the names used by the different Indigenous peoples to identify themselves.

In colonial times, the altiplano was a multilingual and multiethnic region with a predominant presence of Aymara-speaking communities. When the Spanish arrived (1530s), the type of alliances that these Aymara AYMARA POLITIES of THE QULLASUYU in the 16th CENTURY polities had developed with the Inca state had contributed to their consolidation and regional domination. The human landscape, territorial configuration and organizational structure of Andean highland societies were drastically altered under Spanish colonial rule. By organizing the colonial economy around silver production in the famous Potosí mines, the colonial state implemented massive resettlement policies, relocating the Indigenous population into fixed targeted villages (Reductions) for a more efficient extraction of surplus and Indigenous labor. The dispossession in this process took the form of a complete dismantling of the political and economic structure of the large Aymara polities, their fragmentation into a multiplicity of smaller “Indian communities” and the recreation of new ethnic links on a much smaller scale. Although these “Indian communities” were given access to land and were able to recreate elements of their social organization —as ayllu or marka—, they were integrated into colonial society as a source of labor and surplus extraction and collection.

The contemporary process of recovering the right to Indigenous territories and autonomies began in 1990 with the “March for Territory and Dignity.” This milestone stirred different governments to recognize the right to collective property, titling areas as “Indigenous lands,” especially in the Bolivian lowlands. By 1996, the existing legislation recognized the existence of “Tierras Comunitarias de Origen” (TCO), to be replaced by a much broader piece based on territorial rights and autonomies, enshrined in the 2009 Constitution, with the legal wording and formulation of the “Territorios Indígenas Originarios Campesinos” (TIOCs).2

Today, the Indigenous communities of the southern half of the altiplano are, in general, Qhishwa speakers and tend to identify themselves as members of the Qhishwa/Quechua nation, while the Indigenous communities of the northern half of the altiplano are Aymara speakers and identify themselves as members of the Aymara nation. In the middle of these lands, around the lakes, there are smaller communities of Uru-Chipaya speakers.

It is quite remarkable that 69% of the area of titled TIOC in this sub-region is in the department of Potosí. The total number of titled TIOCs in the Altiplano is 34, comprising 6.6 million titled hectares, i.e., 32% of the titled TIOC area in the country. 3

REFERENCES:

Albó, Xavier and Carlos Romero. Autonomías Indígenas en la Realidad Boliviana y su Nueva Constitución. La Paz: Vicepresidencia del Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia, 2009.

Plurinational State of Bolivia. Constitución Política del Estado. La Paz: Gaceta Oficial del Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia, 2009.

Fundación Tierra. Territorios Indígena Originario Campesinos en Bolivia. Entre la Loma Santa y la Pachamama, Informe 2011. La Paz: Fundación Tierra, 2011.

Plurinational State of Bolivia. *Constitución Política del Estado (*La Paz: Gaceta Oficial del Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia, 2009).

- ↩︎

Fundación Tierra. Territorios Indígena Originario Campesinos en Bolivia. Entre la Loma Santa y la Pachamama, Informe 2010. (La Paz: Fundación Tierra, 2011); Xavier Albó and Carlos Romero. *Autonomías Indígenas en la Realidad Boliviana y su Nueva Constitución (*La Paz: Vicepresidencia del Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia, 2009). ↩︎

Fundación Tierra. Original Indigenous Peasant Territories in Bolivia. ↩︎