Abstract

The map shows the Indigenous territories that were officially recognized by the Plurinational State of Bolivia in 2011. This means that, by that time, Indigenous organizations representing Indigenous peoples, or nations inhabiting certain defined areas had received property titles granting them the right to collective ownership over them. According to legislation based on the 2009 Bolivian Constitution, which came into force during Evo Morales´ administration, this collective property was described as inalienable, indivisible, irreversible, unseizable, and imprescriptible. In this context, Indigenous territories are understood as territorial units that constitute the habitat of Indigenous peoples where they have the right to maintain and develop their own forms of economic, political, social, and cultural organization, as well as the right to the use and management of all renewable resources. The map also shows areas that were in the process of applying for property titles in that same year1

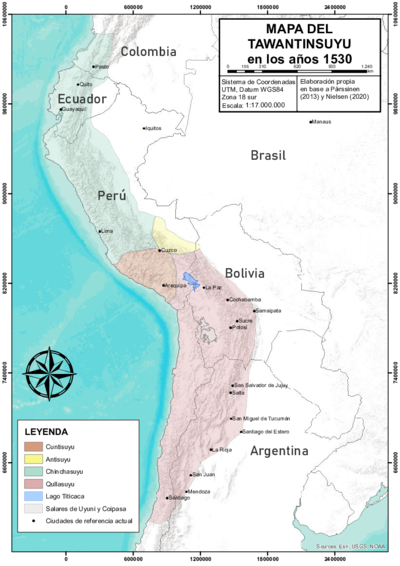

It is worth noting that in pre-colonial times, the highlands of Bolivia —inter-Andean valleys and high plateau yellow-colored on the map— were part of the Qullasuyu, i.e., the southern district of the Inca state or Tawantinsuyu. The lowland peoples (area on the map in green), although they were in constant interaction with the Inca state, were non-state societies and never came under its control.

Before the lawful consolidation of the “Territorios Indígenas Originarios Campesinos” —“Native Indigenous Peasant Territories,” TIOCs as per its acronym in Spanish—, the existing legislation recognized the existence of “Native Community Lands” or “Tierras Comunitarias de Origen” —TCO as per its acronym in Spanish. This legitimate formulation was incorporated in Act 1715, known as “INRA” Act —acronym standing for the National Institute of Agrarian Reform—, in 1996, during the neoliberal government of Sánchez de Lozada. One of the official arguments put forth in opposition to the concept of “Indigenous territory” was that, according to the Government, it could jeopardize the country´s unity, since the Indigenous peoples, by way of “self-determination,” could demand their disintegration. The various neoliberal governments that ensued would try to ensure that the collective rights granted would not exceed land rights. However, thanks to Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization, it was determined that TCOs should be used as synonymous with “Indigenous territory”, with property rights over land and over renewable natural resources.

During the Constituent Assembly —convened between 2006 and 2008—, the discussion was taken up again, this time in a different political scenario. The territorial rights of Indigenous peoples won with the TCOs would be constitutionalized under the concept of “territory,” although not precisely as “Indigenous territory.” The Indigenous assembly members from the highlands tried to ensure that the concepts of “native” and “peasant” were also included in the Constitution. The assembly members´ Solomonic solution was to broaden the term “Indigenous territory” to “native Indigenous peasant territory,” “a new term to acknowledge collective rights to all the human collective that shares cultural identity, language, historical tradition, institutions, territoriality and worldview, whose existence is prior to the Spanish colonial invasion.2

Therefore, what does the title “Territorio Indígena Originario Campesino” (TIOC) mean? It responds to the intention of maintaining the different denominations used by different Indigenous groups to identify themselves: a. Campesino (peasant) is the term generally used by Indigenous people who were subject to the hacienda regime especially in the inter-Andean valleys and some regions of the altiplano and who, through their struggles, achieved private land ownership with the agrarian reform of 1952. b. Originario (native) is the term generally used by those Indigenous people who, through their struggles, managed to resist the advance of the hacienda by maintaining themselves as Indigenous communities with some form of collective management of agricultural space. c. Indígenas, a generic term for all, came up as a strong word in the struggles for territory beginning in the 1980s. In summary, these differences in the terminology employed represent the diverse historical processes and political projects that have defined the different Indigenous populations of Bolivia.

Supreme Decree No. 727 issued in 2010 established that existing TCOs would be renamed TIOCs and future TCOs would acquire the same name. The TIOCs were characterized as follows according to the State´s Political Constitution:

I. The integral nature of the native Indigenous peasant territory is recognized, including the right to land, to the exclusive use and exploitation of renewable natural resources under the conditions determined by law; to prior and informed consultation and to the participation in the benefits from the exploitation of non-renewable natural resources found in their territories; the power to apply their own rules, administered by their representative structures and the definition of their development according to their cultural criteria and principles of harmonious coexistence with nature. The Indigenous native peasant territories may be composed of communities.

II. The native Indigenous peasant territory includes areas of production, areas of exploitation and conservation of natural resources and spaces of social, spiritual, and cultural reproduction. The law shall establish the procedure for the acknowledgement of these rights. 3

The map displays the titled TIOCs at the national level. That is, the consolidated collective territories where the National Institute of Agrarian Reform (INRA) concluded the process of “curing title” (i.e., the technical procedure aimed at legalizing the land property rights), in response to the demands by the native Indigenous peasant nations and peoples. All TIOCs had final resolutions of “saneamiento,” or “curatorial clearance” and executory titles or property titles signed by the President of the Plurinational State of Bolivia.

In summary, the process of recovering the right to Indigenous territories and autonomies began in 1990 with the historic “March for Territory and Dignity”. From that moment on and in response to that march, different governments recognized the right to collective property and titled areas as “Indigenous lands,” especially in the Bolivian lowlands. However, the term “territory” does not enter legislation until the 2009 Constitution, where the terms of the right to territory and Indigenous autonomy are established for the first time. Although the bureaucratic process is cumbersome and complex, as the demands of the peoples have to meet a series of conditions and evidentiary requirements that are not always possible, by 2011, year of publication of the report where this map appears, in all of Bolivia there were a total of 190 TIOCs —34 in the highlands, 101 in the inter-Andean valleys, and 55 in the lowlands, which in territorial terms means 20.7 million hectares titled, that is, 19% of the national area subject to “saneamiento”.4

REFERENCES:

Albó, Xavier and Carlos Romero. Autonomías Indígenas en la Realidad Boliviana y su Nueva Constitución. La Paz: Vicepresidencia del Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia, 2009.

Plurinational State of Bolivia. Constitución Política del Estado. La Paz: Gaceta Oficial del Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia, 2009.

Plurinational State of Bolivia. Decreto Supremo Nº 727. La Paz: Gaceta Oficial del Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia, 2010.

Fundación Tierra. Territorios Indígena Originario Campesinos en Bolivia. Entre la Loma Santa y la Pachamama, Informe 2010. La Paz: Fundación Tierra, 2011

Fundación Tierra. Territorios Indígena Originario Campesinos en Bolivia. Entre la Loma Santa y la Pachamama, Informe 2010. (La Paz: Fundación Tierra, 2011); Xavier Albó and Carlos Romero. *Autonomías Indígenas en la Realidad Boliviana y su Nueva Constitución (*La Paz: Vicepresidencia del Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia, 2009). ↩︎

Plurinational State of Bolivia. *Constitución Política del Estado (*La Paz: Gaceta Oficial del Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia, 2009), Art. 30. ↩︎

Plurinational State of Bolivia. *Constitución Política del Estado (*La Paz: Gaceta Oficial del Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia, 2009), Art. 403. ↩︎

Fundación Tierra. Territorios Indígena Originario Campesinos en Bolivia, 27. ↩︎