Abstract

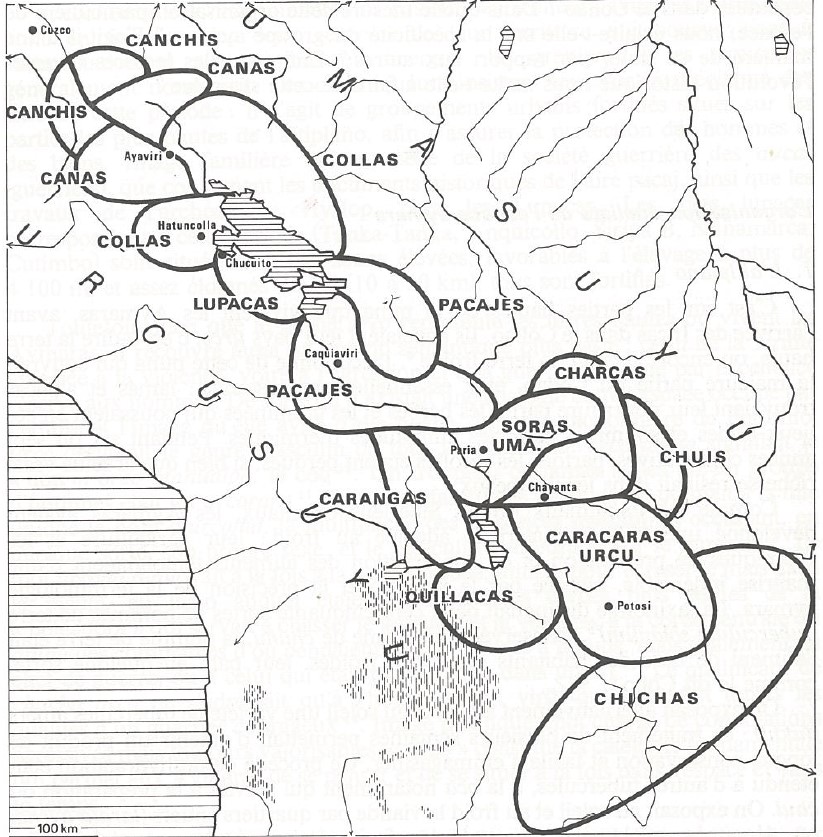

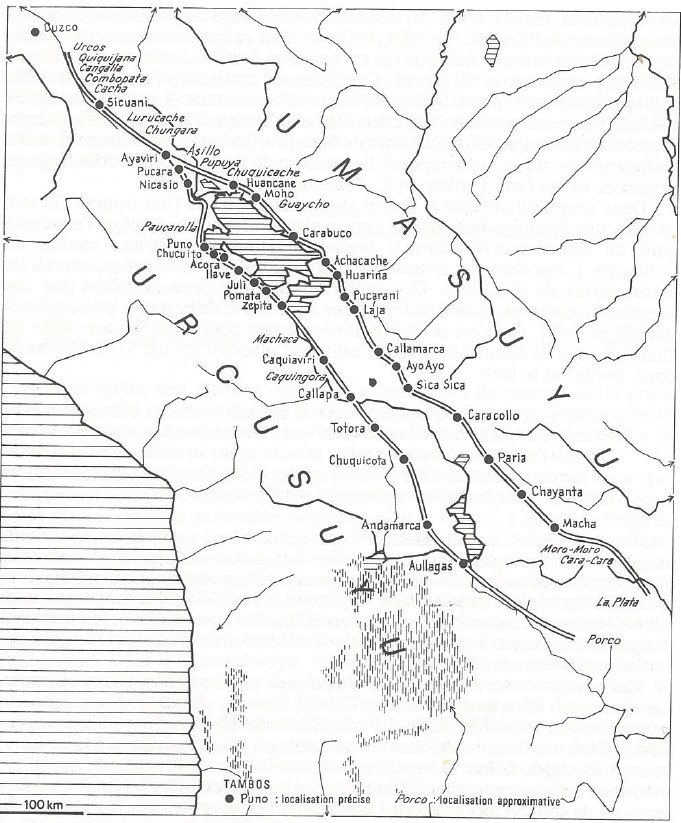

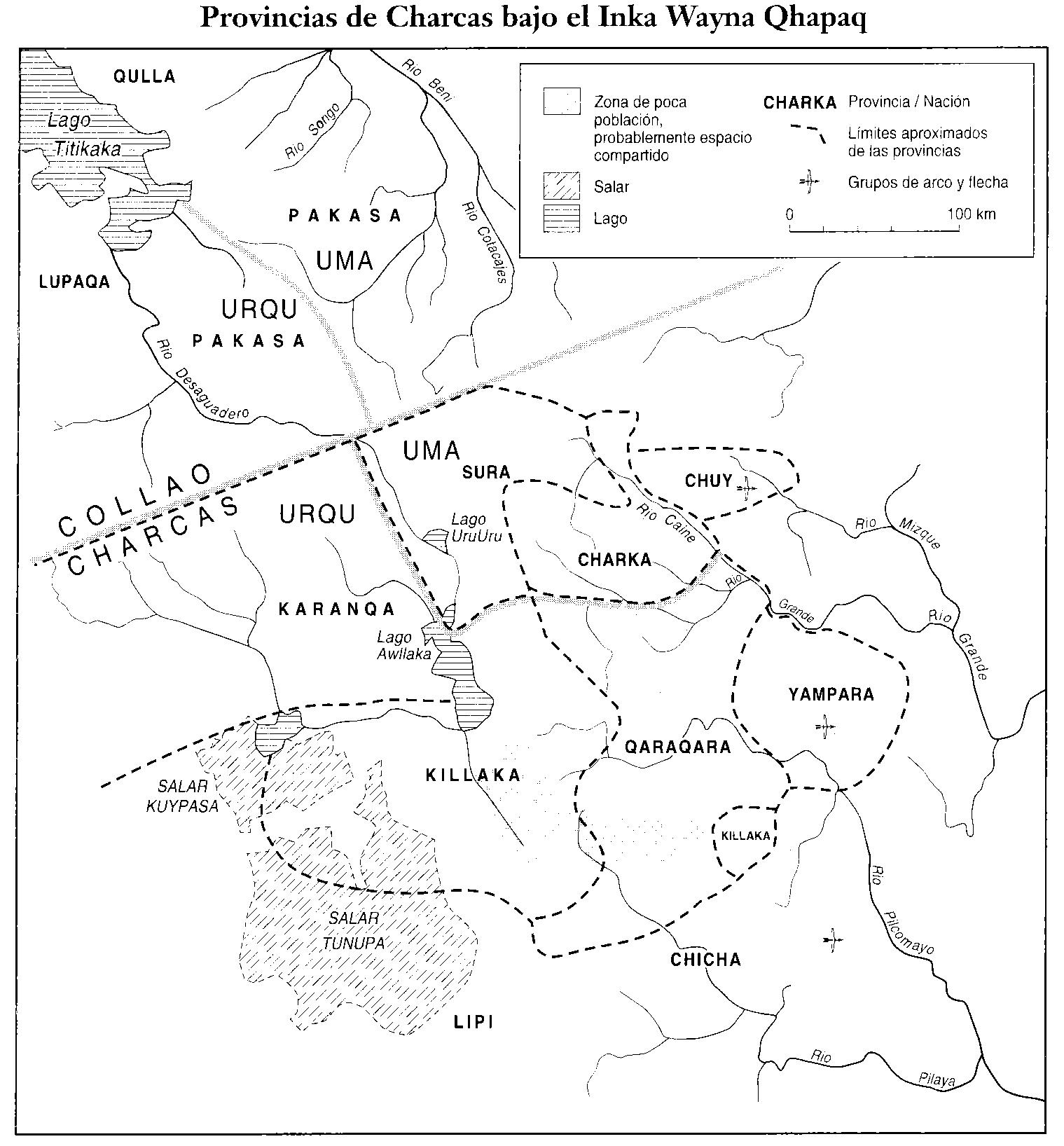

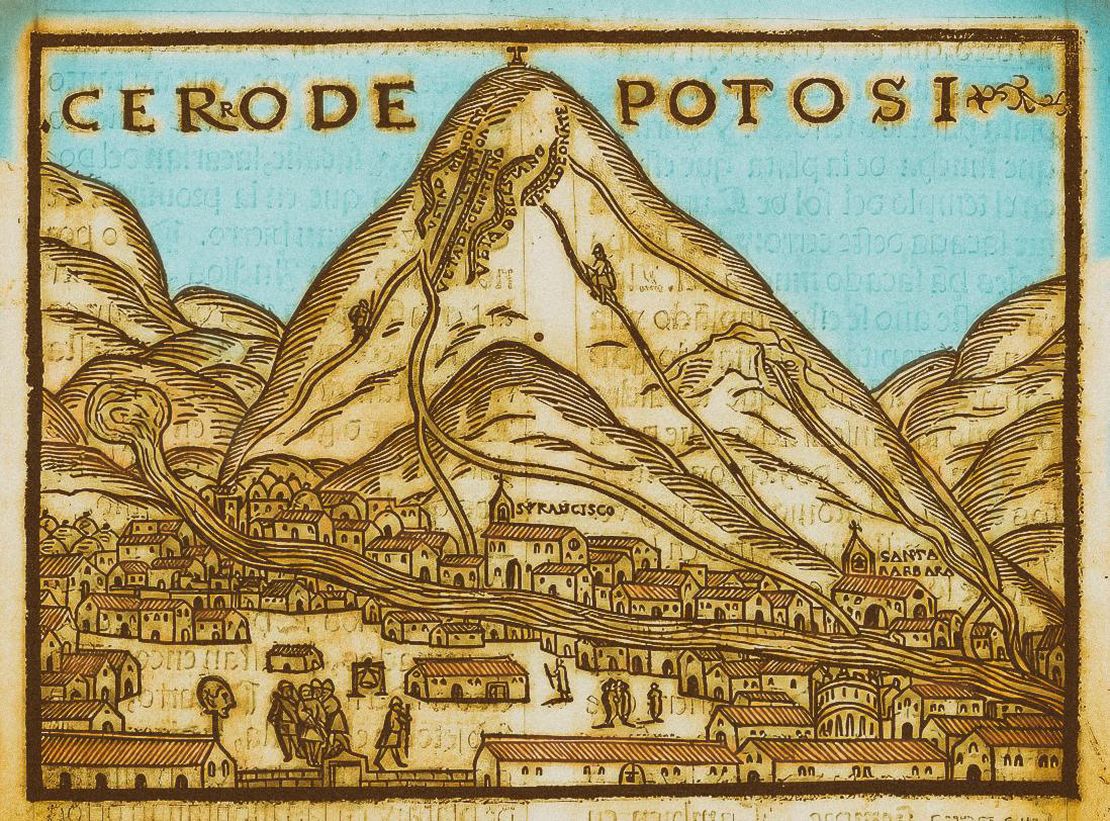

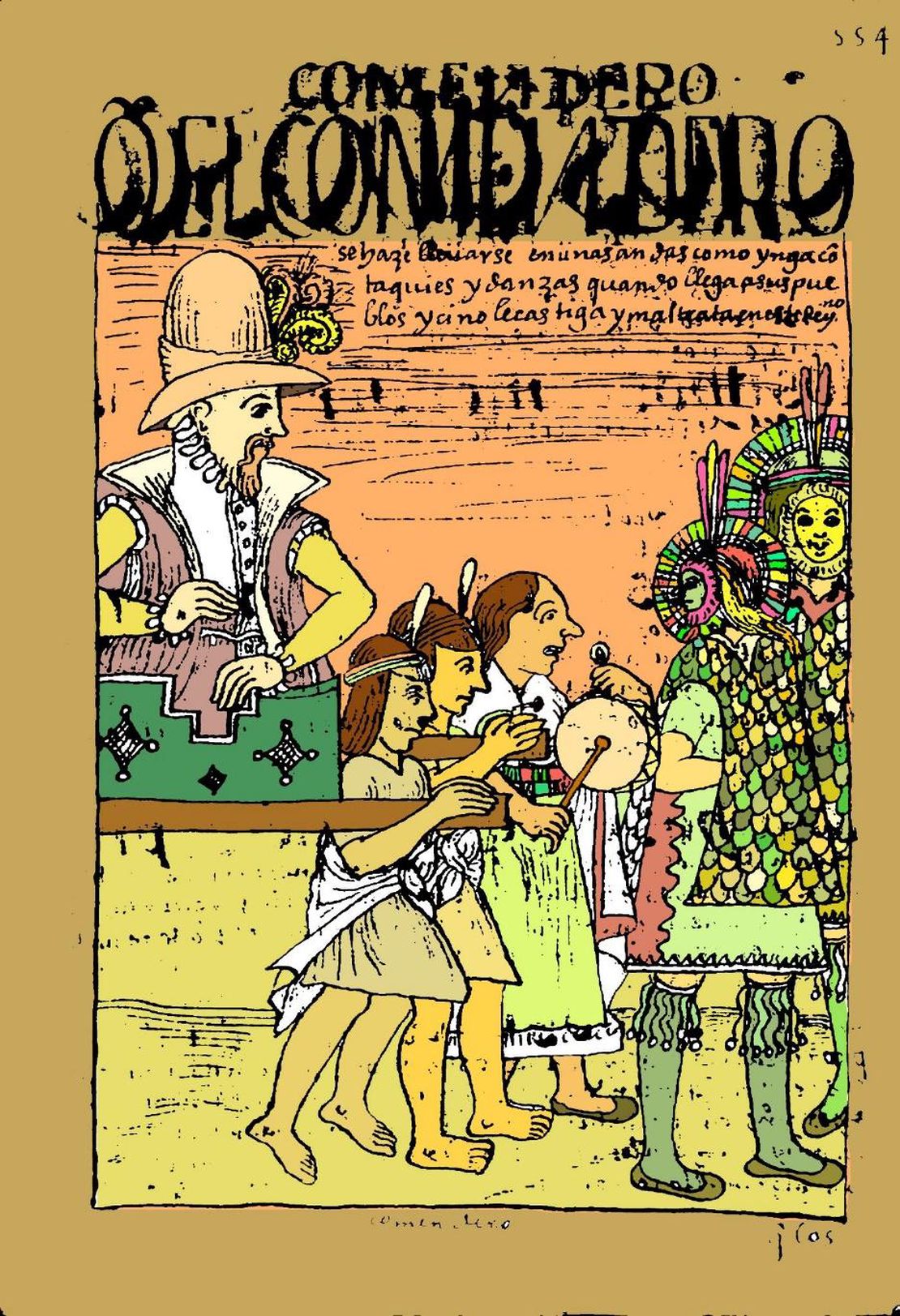

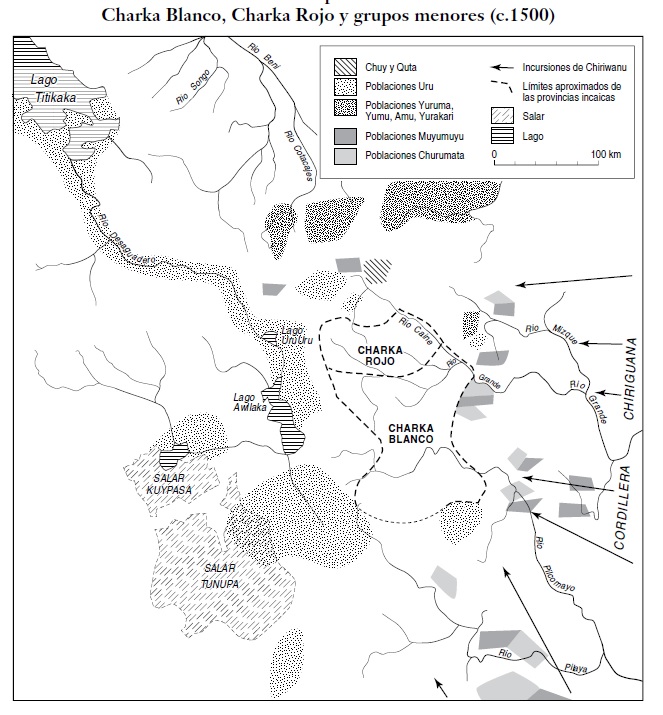

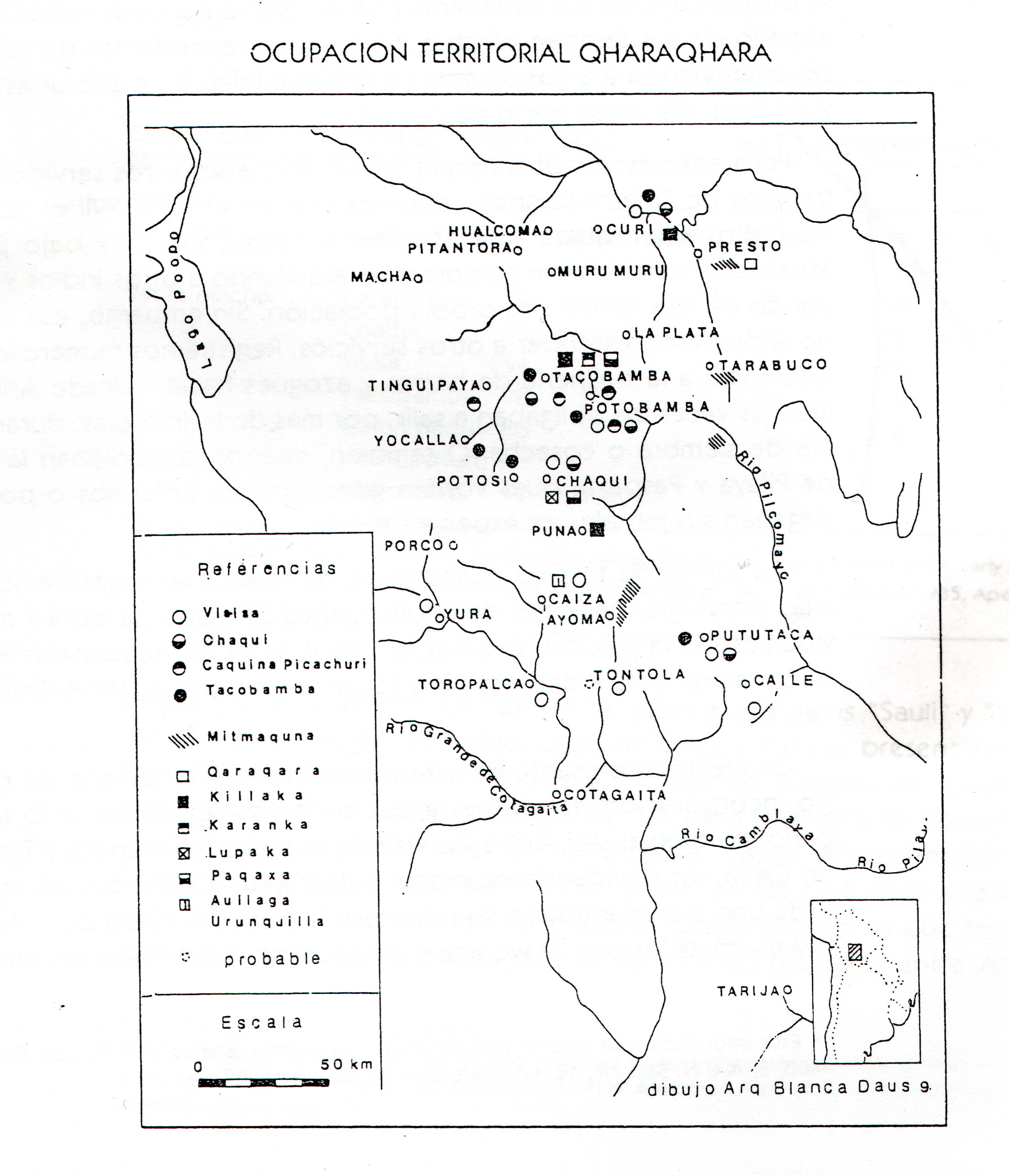

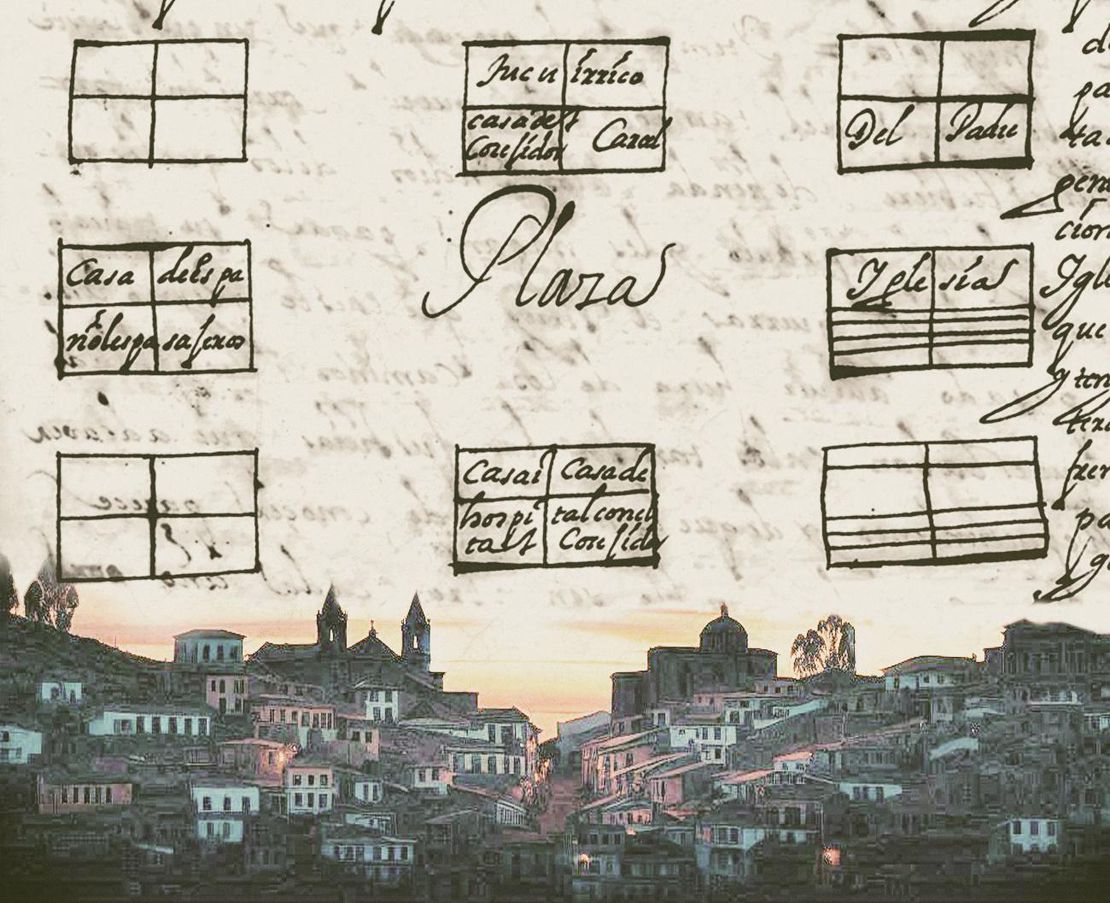

Drawn on the background of a satellite photograph and using ethnohistoric and archaeological information, this map shows the approximate location of the Pueblo Real de Indios or [Reducción](/en/content/TL003Reducciones/) de Talina, under Spanish rule in the late 16th century. In pre-colonial times, this territory was part of the [*Qullasuyu*](/en/content/BOL0002Y/), the southern district of the Inca state, a territory controlled by the [Aymara](/en/content/BOL0003Y/) lordship of the [Chichas](/en/content/BOL0028Y/). Following the model of vertical control of ecological layers and discontinuous territoriality AYMARA POLITIES of THE QULLASUYU in the 16th CENTURY , the Chichas settlements were in the high plateau region and in ecological niches along the inter-Andean valleys of present-day southwestern Bolivia. Major reforms enforced by the colonial state in the 1570s imposed the relocation of dispersed settlements into clustered villages. While the Chichas were able to gain access to land, **dispossession took the form of a complete rearrangement of their territorial organization and a disarticulation of their large political system into a variety of communities fragmented into Reductions**, as was the case of Talina.[^1]At the beginning of the 16th century the Aymara lordship of the Chichas QULLASUYU PROVINCES UNDER INCA RULE EARLY 16TH CENTURY belonging to the Qara Qara-Charka confederation, was scattered along the Inca road INCA ROADS AND TAMBOS in the 16th CENTURY that went through the present-day Calcha, Cotagaita, Tupiza, Talina —the present map examines this Reduction—, Suipacha, Moreta and other settlements that were mostly located along the watercourse of the rivers flowing down to the east.

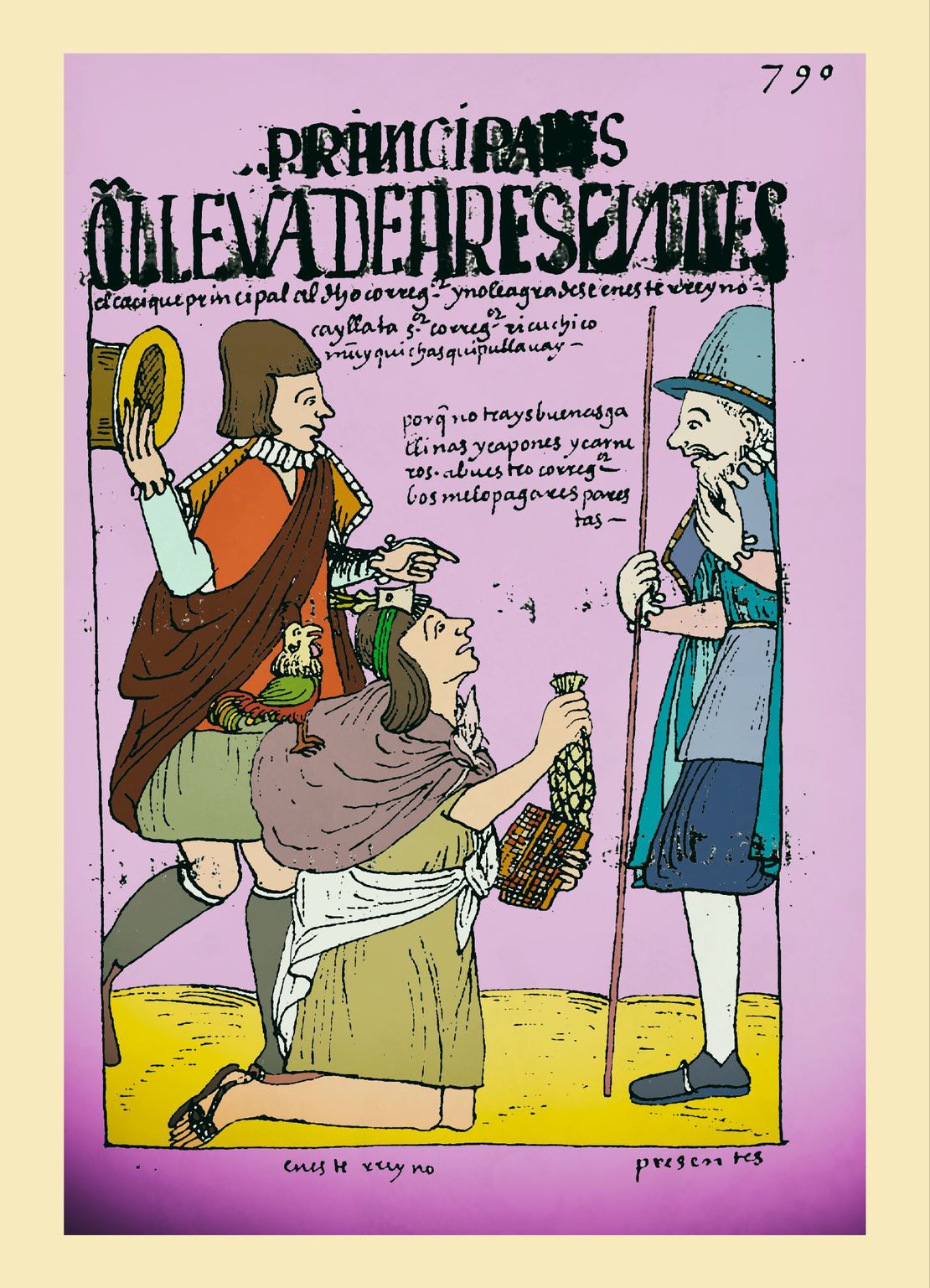

According to the Toledo Tax, as of the 1573 census, the entire Chichas population was settled in 19 villages.1 Nine of these villages were concentrated in Talina and the other ten were rearranged between Calcha and Cotagaita, which means that the concentration of dispersed population was more acute in Talina. With the reductions, the process of fragmentation and alienation of the discontinuous territories controlled by this socio-political unit was deepened, these territories were reorganized and the Indigenous authorities (kurakas) became officials paid by the colonial state to collect the Indigenous tribute and recruit the compulsory labor force under the mita system. In turn, the reductions generated the release of large plots of land that would later be sold as part of the land compositions.

The 1573 census, known as Toledo´s General Visit, allowed the Crown to obtain statistical information about the Chichas. According to data from this census, total population amounted to 3,164 people, the taxpaying population reached 834 among adult males between 18 and 50 years old, 520 from Calcha and 314 from Talina; 217 people were noted as “old and disabled Indians who do not pay taxes”, 720 as boys up to 17 years old, and 1398 as women “of all ages and states”. 2

The Talina Reduction was in the central-eastern sector of a wide area in the puna, with a plain interrupted by the ravines formed by the Grande de San Juan River (as it is known in Argentina) or San Juan del Oro River (as it is called in Bolivia). The Reduction includes the puna highlands located south of the watercourse of said river, and the highlands and ravines and rivers integrated to the San Juan del Oro watercourse.

In 1646, the bitter experiences led to the Chichas´ decision to collect and save the money destined to the payment of their land composition. 3 Thus, throughout the vast region, private property was imposed early on, with haciendas in charge of very few families, except for those that managed to buy as part of the lands sold in composition, as ayllu property, that is, the organizational social cell composed of an extensive network of households. The rest were acquired by Spaniards as haciendas.

The most important of these haciendas, which occupied part of the territory previously controlled by the Chichas, is that of the Marquisate of the Tojo Valley, from the 17th century to the end of the 19th century, which covered a large part of the current border strip between Argentina and Bolivia, and owned the largest encomienda of Indians from Tucumán: Casabindo and Cochinoca, in the current Jujuy puna. The belonging of These important ethnic groups as part of the Chichas´ Aymara lordship of the, has been a source of controversy —at least partially—, among activists and scholars.4

The wars of independence with Spain affected the functioning of the trade circuits and commercial ties in the region, which —added to the collapse of mining in Potosí—, made leasing, the use of land in exchange for a determined price, the practical solution. The Marquesate hacienda model controlled the territory and the population in the region into a model of servitude that was maintained since colonial times and lasted well into the 20th century.5

With the advent of the Argentine and Bolivian Republics, the characteristics of the former Marquisate remained practically intact, unlike other parts of Argentina, where lands formerly owned by the community, were declared fiscal. In Potosí, Indigenous communal ownership was maintained until 1901.

The descendants of the Chichas socio-political unit were able to exempt themselves from the provisions of the 1874 Land Dispossession Act, in favor of individual ownership thanks to the land composition titles granted to them in 1646. For this to become effective, they had to conduct a series of actions in the last two decades of the 19th century and the first two decades of the 20th century, so that they would not be included in the operations of the monitoring mesas revisitadoras, which, in the style of the Toledo visits, were carried out by state agents in favor of the local landowners. Calcha, for example, managed to get rid of the monitoring and evaluation revisitas, however, a new front emerged against the territories that came from the haciendas on the region´s borders, having to file lawsuits until well into the 20th century, which they managed to win, although many times there were clashes to defend their land against the bosses who came with armed laborers.6

Though some goals could not be accomplished with the Land Dispossessions Act, the 1953 Agrarian Reform achieved the consolidation of individual property rights of small and medium landowners who had entered the boundaries of the ayllus territories. The Agrarian Reform was perceived in many of Potosí rural areas as a continuation of the state’s efforts to destroy the territorial and social integrity of the ayllus.7

In the years following the Agrarian Reform, most of the settlers of the Chichas region sustained the reasoning that the State was the owner of the land and by paying the tax, they would secure their legitimate possession. The total amount would be deposited in the Departmental Treasury located in the Prefecture of Potosí, until the enactment of Act 843 in the Tax Reform (1986): “This law declared the end of the collection of this old tax of colonial origin […] but in Calcha the authorities continued making this payment to the state until the 1990s, seeing it as necessary to maintain the ownership of their lands and their role as authorities". 8 This “obligation” was maintained by other ayllus in the department of Potosí.

With the Constitutional Assembly (2007-2008) that derived in the Constitutional Amendment and the Autonomies and Decentralization Act, the Chichas Nation has been to-date organized into eight Community Lands of Origin, six Ayllus, two Jatun Ayllus, and five autonomous municipalities, in addition to the municipalities of Lípez and their respective Community Lands of Origin.

To what extent does the current Chichas Nation acknowledge its origin in the Aymara lordship of the Chichas peoples of the 16th century? Many Chicheños, mainly from the town of Tupiza, including teachers and writers, are advocating for the cause of recreating the Chichas Nation based on the pre-Hispanic past of that ethnic group, although without emphasizing the Aymara culture or language. The creation of the Chichas Nation is inscribed in a political timeline in which, thanks to the possibilities opened by the current constitution of the Plurinational State, enabling such a statement, these characteristics do not always coincide with the results of the academic studies conducted on the Chichas. As Zanolli states, there is no consensus about the language spoken by the Chichas.9 According to the Chichas Nation, the communication channel was through Kunza.10 There is also no consensus on the broad territoriality assigned to the Chichas in the refoundational document, including a good part of the Argentine provinces of Jujuy and Salta.

REFERENCES:

Cook, Noble David, ed. Tasa de la Visita General de Francisco de Toledo. Lima: Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, 1975.

Frías Mendoza, Víctor Hugo. Mistis and Mokochinches. Mercado, Evangélicos y Política Local en Calcha. La Paz: Mama Huaco, 2002.

Madrazo, Guillermo. Hacienda and Encomienda in the Andes. The Argentine Puna under the Marquisate of Tojo. Siglos XVII a XIX. Buenos Aires: Fondo Editorial, 1982.

Palomeque, Silvia. “The Chichas and the Toledan Visits. The Lands of the Chichas of Talina (1573-1595).” Surandino Monographic, 1, 2 (2010): 1-76.

Tarcaya, Freddy. Kunza, the Language of the Chichas Nation. Cochabamba: Kipus, 2015.

Teruel, Ana, “El Marquesado del Valle de Tojo: ¨Patrimonio y Mayorazgo. From the seventeenth to the twentieth century in Bolivia and Argentina.” Revista de Indias, LXXVI (2016): 267,379-418.

Zanolli, Carlos. “Incidences, Uses and Appropriations of Academic Knowledge by Society: the Cases of Humahuaca (Argentina) and the Chichas Nation (Bolivia).” ISHIR Studies, 12, 32 (2022), 1-18.

http://portal.amelica.org/ameli/journal/422/4223173008/html/

Palomeque, “Los Chichas y las Visitas Toledanas”. ↩︎

Noble David Cook, Tasa de la Visita General de Francisco Toledo, (Lima: Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, 1975), 315. ↩︎

Palomeque, “Los Chichas y las Visitas Toledanas”, 2. ↩︎

Guillermo Madrazo, Hacienda and Encomienda in the Andes. La Puna Argentina bajo el Marquesado de Tojo. Siglos XVII a XIX. (Buenos Aires: Fondo Editorial, 1982). ↩︎

Ana Teruel, “El Marquesado del Valle de Tojo: Patrimonio y Mayorazgo. Del siglo XVII al XX en Bolivia y Argentina.” Revista de Indias, LXXVI, 267 (2016), 379-418. ↩︎

Víctor Hugo Frías Mendoza, Mistis y Mokochinches. Mercado, Evangélicos y Política Local en Calcha (La Paz: Mama Huaco, 2002). ↩︎

Victor Hugo Frias Mendoza, Mistis and Mokochinches, 36. ↩︎

Victor Hugo Frias Mendoza, Mistis and Mokochinches, 40. ↩︎

Carlos Zanolli, “Incidences, Uses and Appropriations of Academic Knowledge by Society: the Cases of Humahuaca (Argentina) and the Chichas Nation (Bolivia).” ISHIR Studies, 12, 32 (2022), 1-18. ↩︎

Freddy Tarcaya Gallardo, Kunza, el Idioma de la Nación Chichas (Cochabamba: Kipus, 2015). ↩︎