Abstract

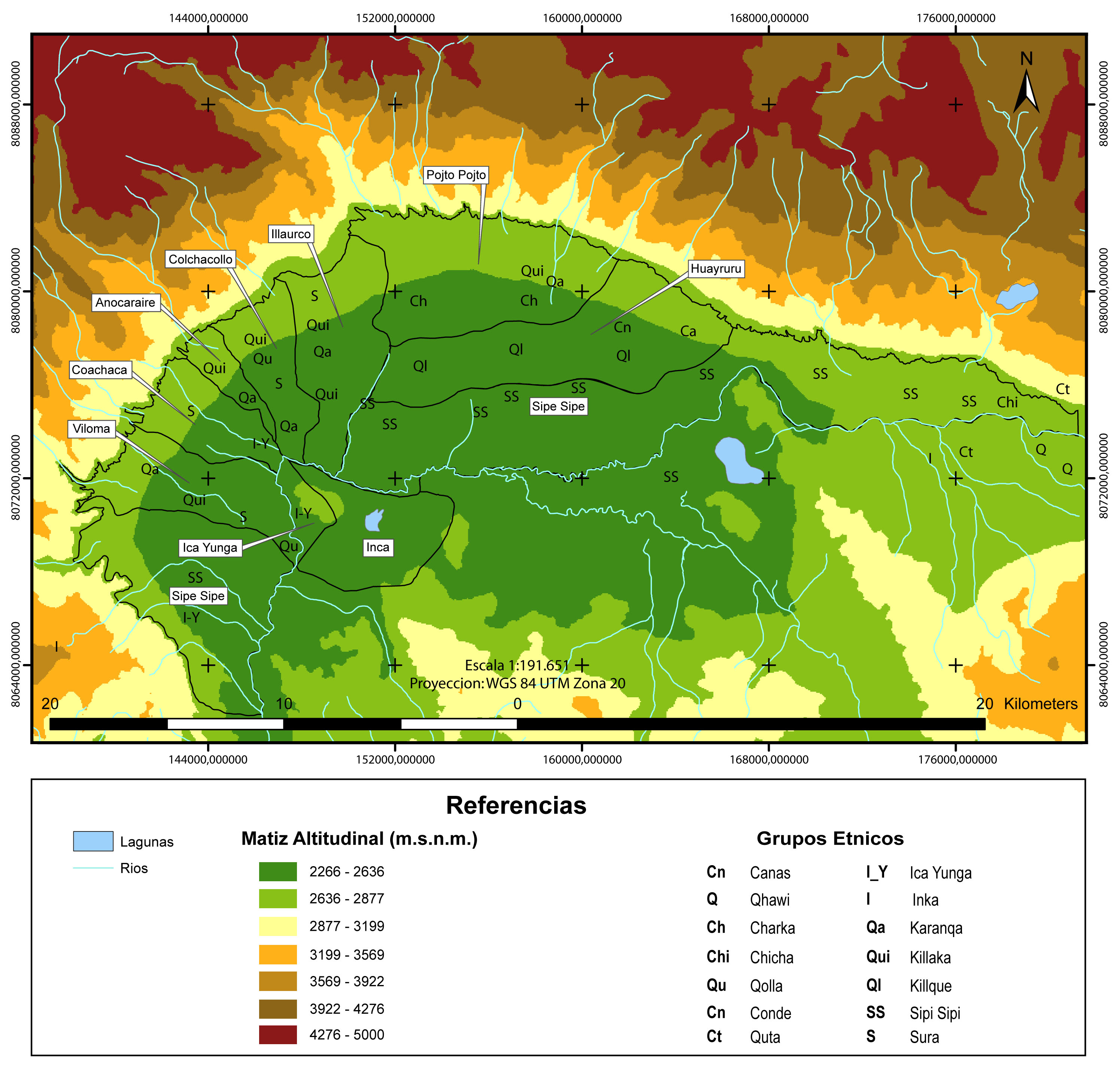

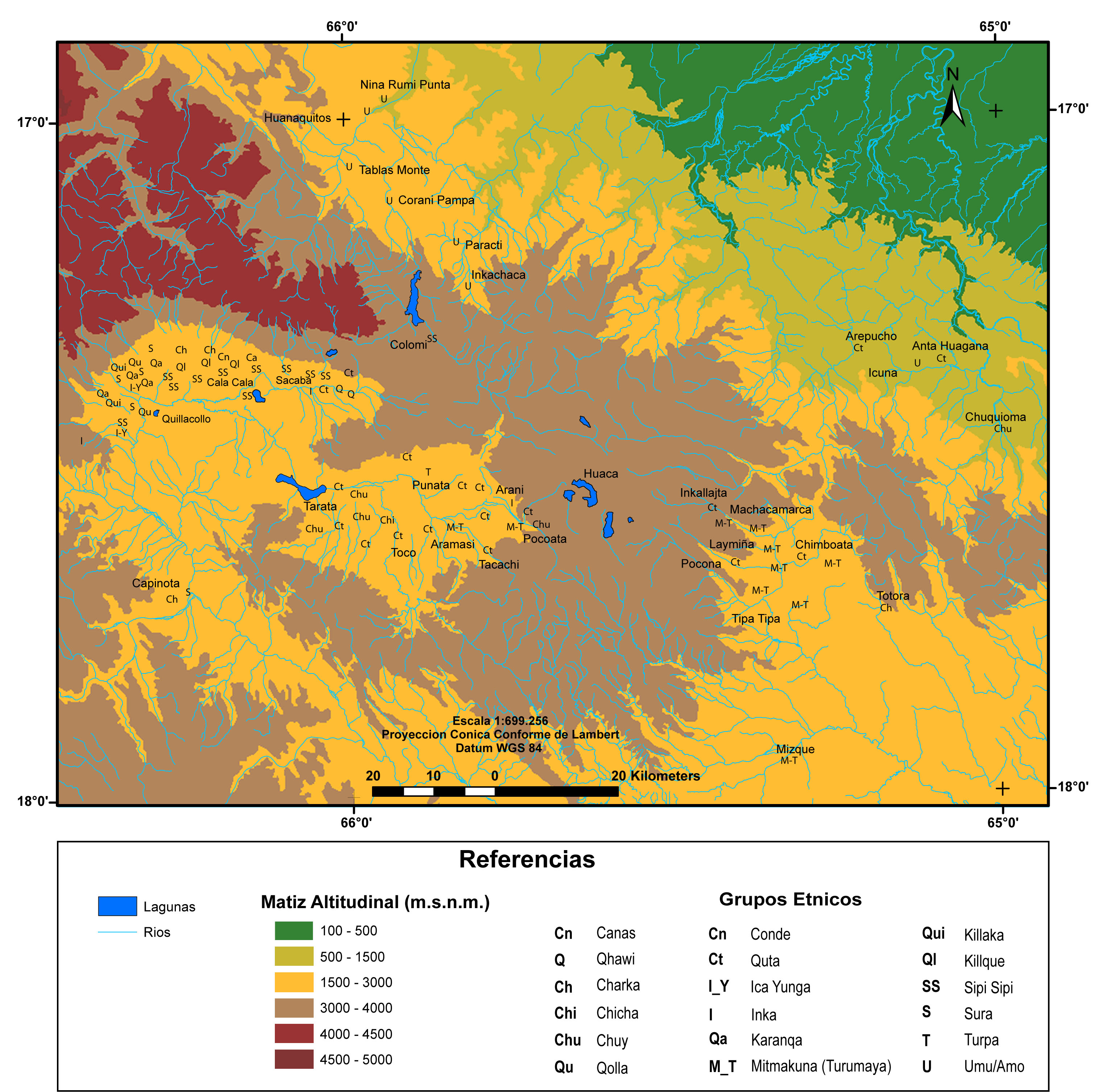

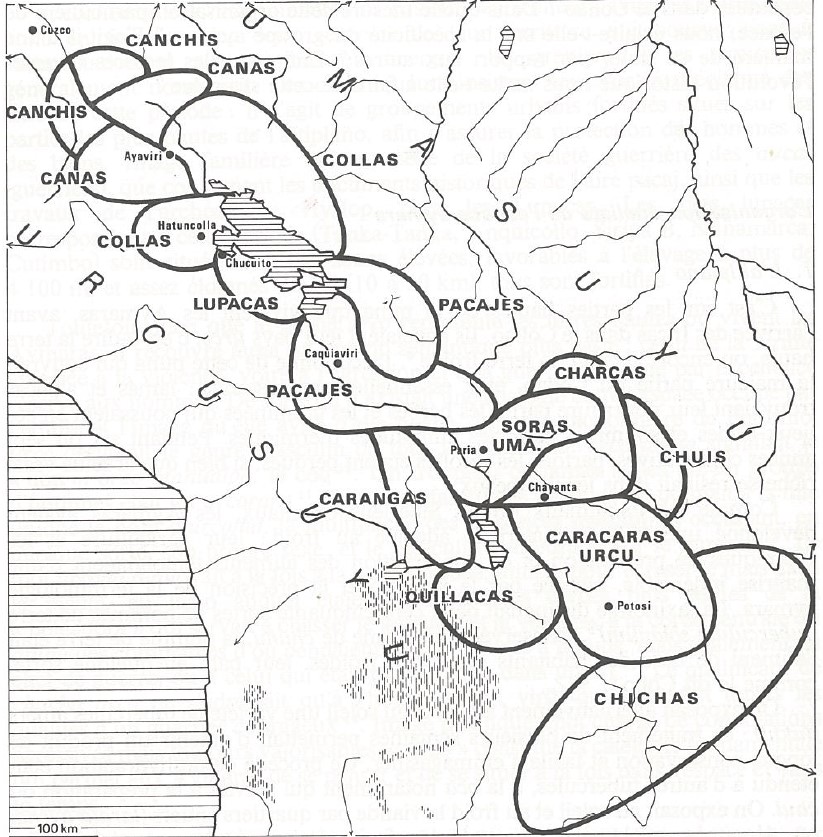

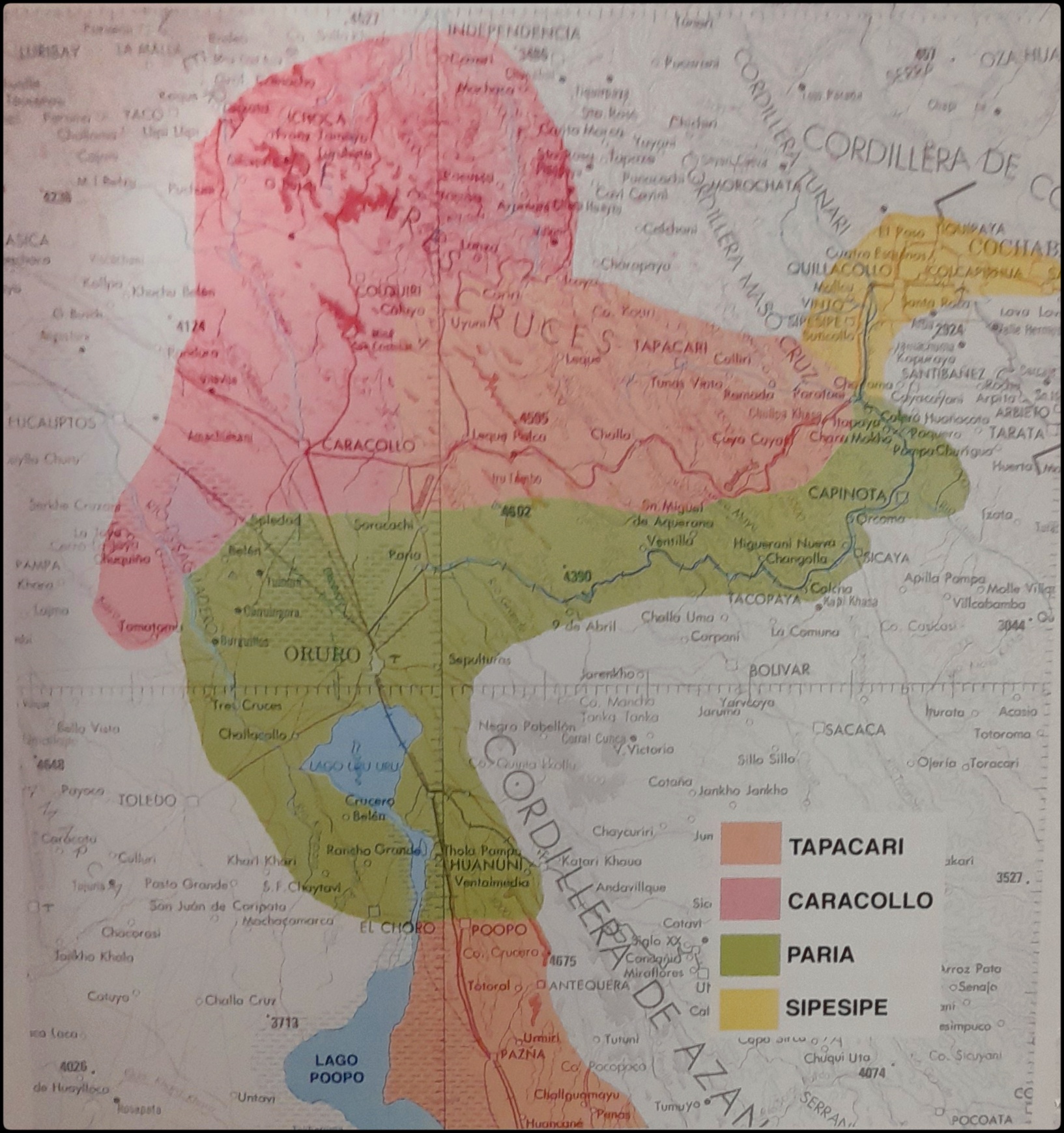

This map illustrates the multi-ethnic composition of the Lower Valley (Valle Bajo) in present-day Cochabamba, Bolivia, as a result of Inca resettlement policies in the early 1500s.1 The so-called “valleys of Cochabamba” consist of three contiguous valleys—Lower, Central, and Upper—that together form a large, fertile region running west to east. This map focuses on the western part, i.e., the Lower Valley. The Incas, claiming these lands as state domains, transferred much of the valley’s original inhabitants further east, replacing them with large groups from other districts of the Inca State (i.e., the Tawantinsuyu (see THE TAWANTINSUYU IN THE 1530s – TERRITORY OF THE INCA STATE ). In doing so, the Incas transformed this area of the Qullasuyu (i.e., the southern district of the Inca State (see THE QULLASUYU IN THE 1530s – SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF THE INCA STATE )) into a multi-ethnic territory (see MULTI-ETHNIC TERRITORY under INCA DIRECT RULE: THE CENTRAL AND UPPER VALLEYS OF COCHABAMBA in the 1530s ) governed by Inca officials through direct rule.2

The Incas conquered the valleys of Cochabamba in the late 1400s. Claiming these lands as state domains, they set up a large-scale maize production enterprise there in the early 1500s. The main native groups encountered by the Incas in the Lower Valley were the Suras of Sipe-Sipe (see THE AYMARA LORDSHIP OF THE SURAS IN THE 16TH CENTURY ), the Sipesipes (or Sipi-Sipis), the Cotas (or Qutas), and the Chuyes (or Chuis). While large segments of the Quta and Chui populations were uprooted and relocated to the Inca fortresses of Pocona and Mizque, the Suras of Sipe-Sipe and the Sipi-Sipis were allowed to remain and were given important roles in service to the state.

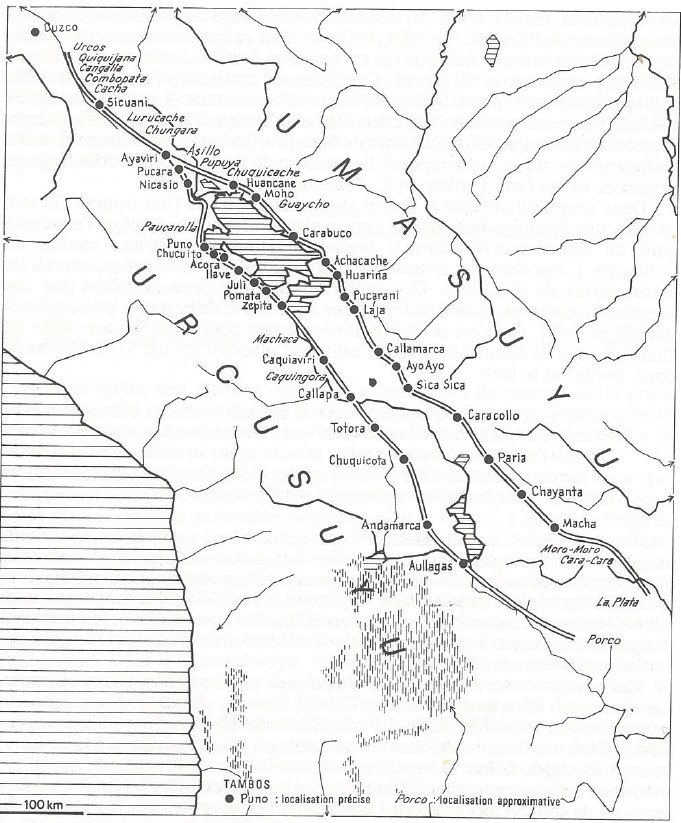

Occupying the higher part of the valley, the Sipi-Sipis were llama raisers and were integrated into the Inca State as llamacamayoc, i.e., those in charge of raising herds of llama for state use. To this end, they were granted large tracts of grassland in the upper regions of the three valleys.3 The Suras of Sipe-Sipe were an Aymara polity (see AYMARA POLITIES of THE QULLASUYU in the 16th CENTURY ) and part of the large Sura Federation, an important, well-respected, and well-rewarded ally of the Incas.4 Under Inca rule, the Suras of Sipe-Sipe managed the transportation of maize from the valleys to high-plateau storage centers along the Inca Road (see INCA ROADS AND TAMBOS in the 16th CENTURY ) and looked after the herds of llamas used to carry it.

As was the case with the Central and Upper Valleys, populations from other regions of the Inca State, primarily from the Aymara polities of the Qullasuyu, were relocated to the Lower Valley to work in the state-run maize production enterprise. This map shows the various ethnic groups that were resettled in this region of the multi-ethnic territory of the valleys of Cochabamba, which were governed by the Incas through direct rule.

Under Spanish colonial rule, these fertile valleys were gradually transformed into haciendas (privately owned estates) concentrating land ownership in the hands of Spanish colonists and their descendants, while the Indigenous people were reduced to the status of hacienda peasants. This transition to haciendas has had long-lasting effects on land ownership patterns, social hierarchies, and economic opportunities in the region. Furthermore, this dispossession was not merely economic but also social and cultural. The Indigenous population lost their means of subsistence and their autonomy, becoming dependent on the hacienda regime.

Nowadays, in the context of the Plurinational State of Bolivia, the descendants of these Indigenous peasants are Qhishwa speakers who, while having maintained some aspects of their heritage, generally identify as members of the Qhishwa (or Quechua) Nation.

REFERENCES:

Del Rio, Mercedes. Etnicidad, territorialidad y colonialismo en los Andes: Tradición y cambio entre los Soras de los siglos XVI y XVII (Bolivia). La Paz: Instituto de Estudios Bolivianos, 2005.

Larson, Brooke. Colonialism and Agrarian Transformation in Bolivia: Cochabamba 1550–1900. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988.

Sánchez, Walter. “‘Indios buenos para la guerra’: Agencia (agency) local y presencia Inka en los Valles de Cochabamba.” In Ocupación Inka y dinámicas regionales en los Andes (siglos XV–XVII), edited by Claudia Rivera Casanovas, 99–122. La Paz: IFEA and Plural editores, 2014.

Wachtel, Nathan. “The Mitimas of the Cochabamba Valley: The Colonization Policy of Huayna Capac.” In The Inca and Aztec States, 1400-1800: Anthropology and History, edited by George A. Collier, Renato I. Rosaldo, and John D. Wirth, 199–235. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press, 1982.

Walter Sanchez, “‘Indios buenos para la guerra’: Agencia (agency) local y presencia Inka en los Valles de Cochabamba,” in Ocupación Inka y dinámicas regionales en los Andes (siglos XV–XVII), edited by Claudia Rivera Casanovas, 99–122 (La Paz: IFEA and Plural editores, 2014), 110. ↩︎

Brooke Larson, Colonialism and Agrarian Transformation in Bolivia: Cochabamba 19550-1900 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988). ↩︎

Walter Sánchez, “‘Indios buenos para la guerra’: Agencia (agency) local y presencia Inka en los Valles de Cochabamba, 110. ↩︎

Mercedes del Rio, Etnicidad, territorialidad y colonialismo en los Andes: Tradición y cambio entre los Soras de los siglos XVI y XVII (Bolivia) (La Paz: Instituto de Estudios Bolivianos, 2005). ↩︎