Abstract

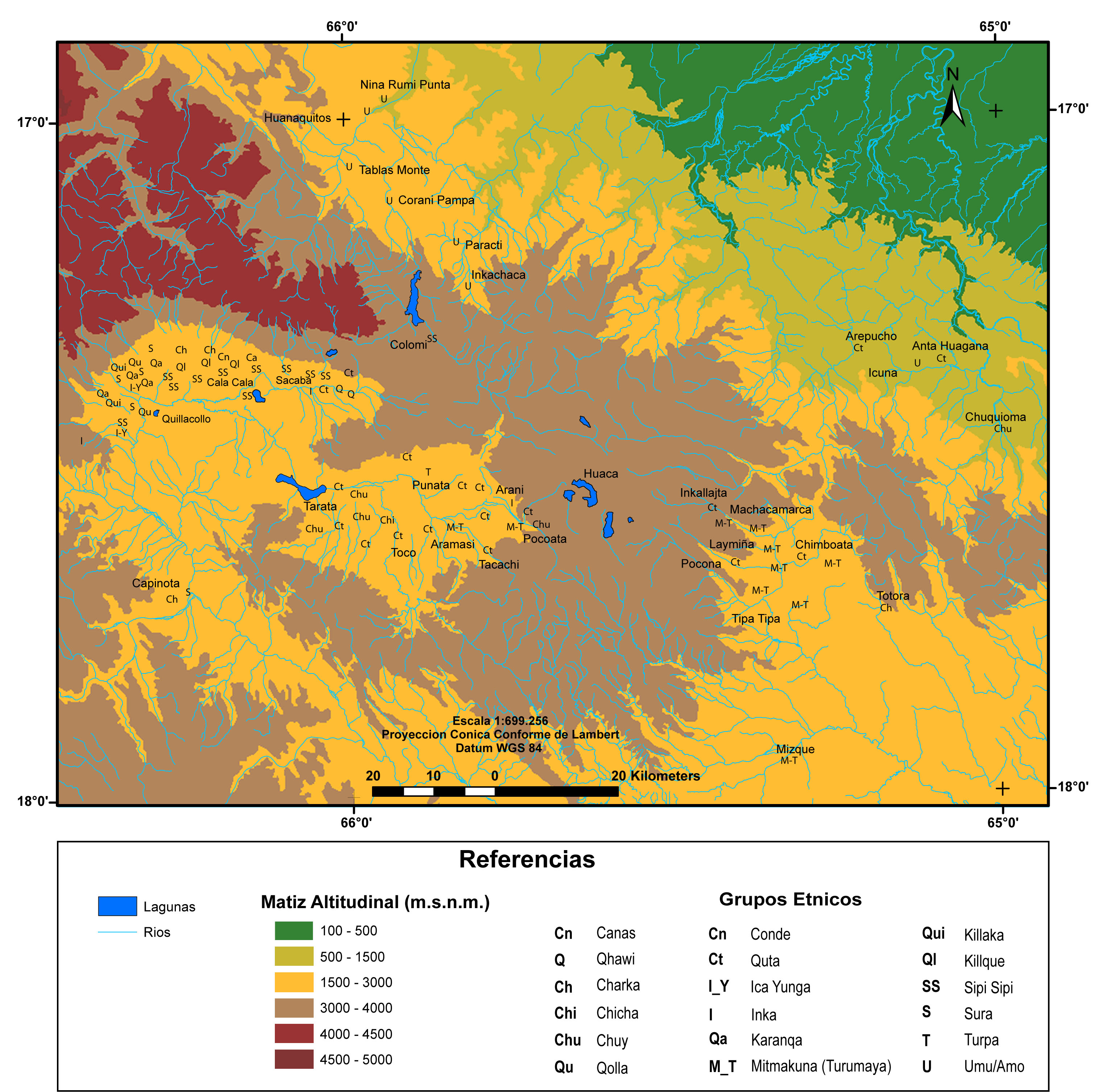

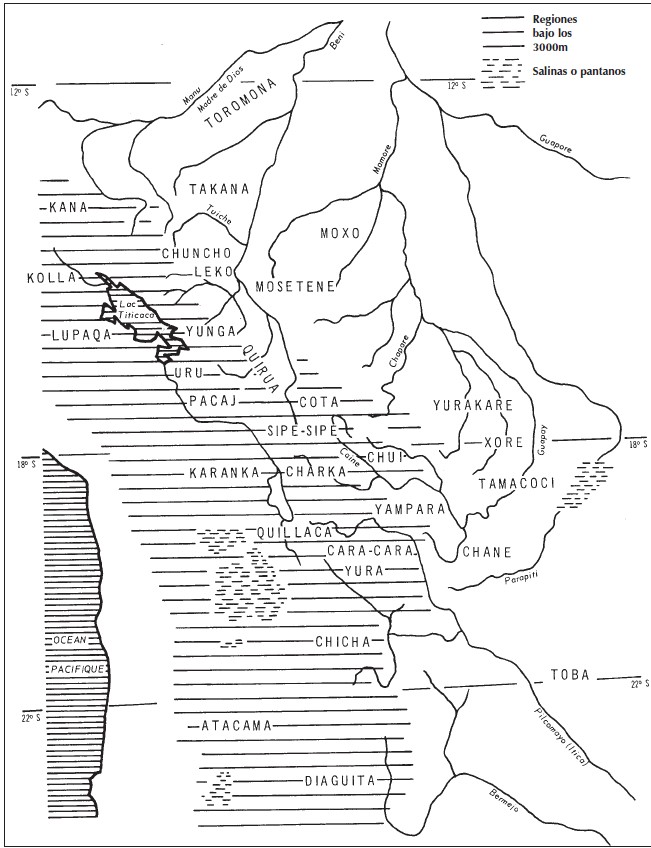

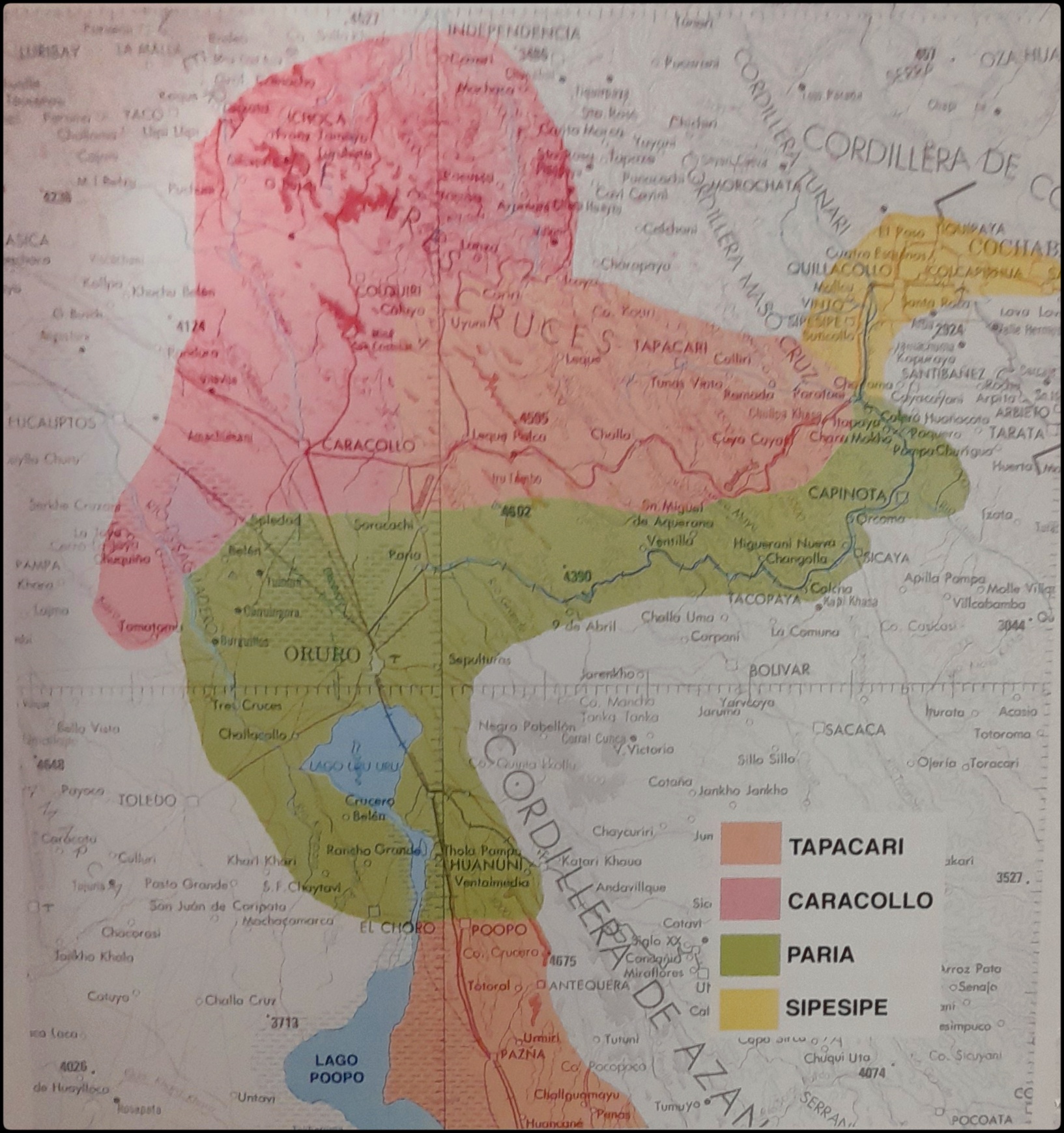

This map illustrates the multi-ethnic composition of the Central and Upper Valleys of present-day Cochabamba, Bolivia, as a result of Inca resettlement policies in the early 1500s.1 The so-called “valleys of Cochabamba” are three contiguous valleys (Lower, Central, and Upper) which, running west to east, form one large, fertile valley. Claiming these lands as state domains, the Incas transferred the autochthonous population further east and brought in groups from other districts of the Inca State, known as the Tawantinsuyu (see THE TAWANTINSUYU IN THE 1530s – TERRITORY OF THE INCA STATE ). Thus, the Incas turned this area of the Qullasuyu (see THE QULLASUYU IN THE 1530s – SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF THE INCA STATE ), the southern district of the Inca State, into a multi-ethnic territory governed directly by Inca officials.2

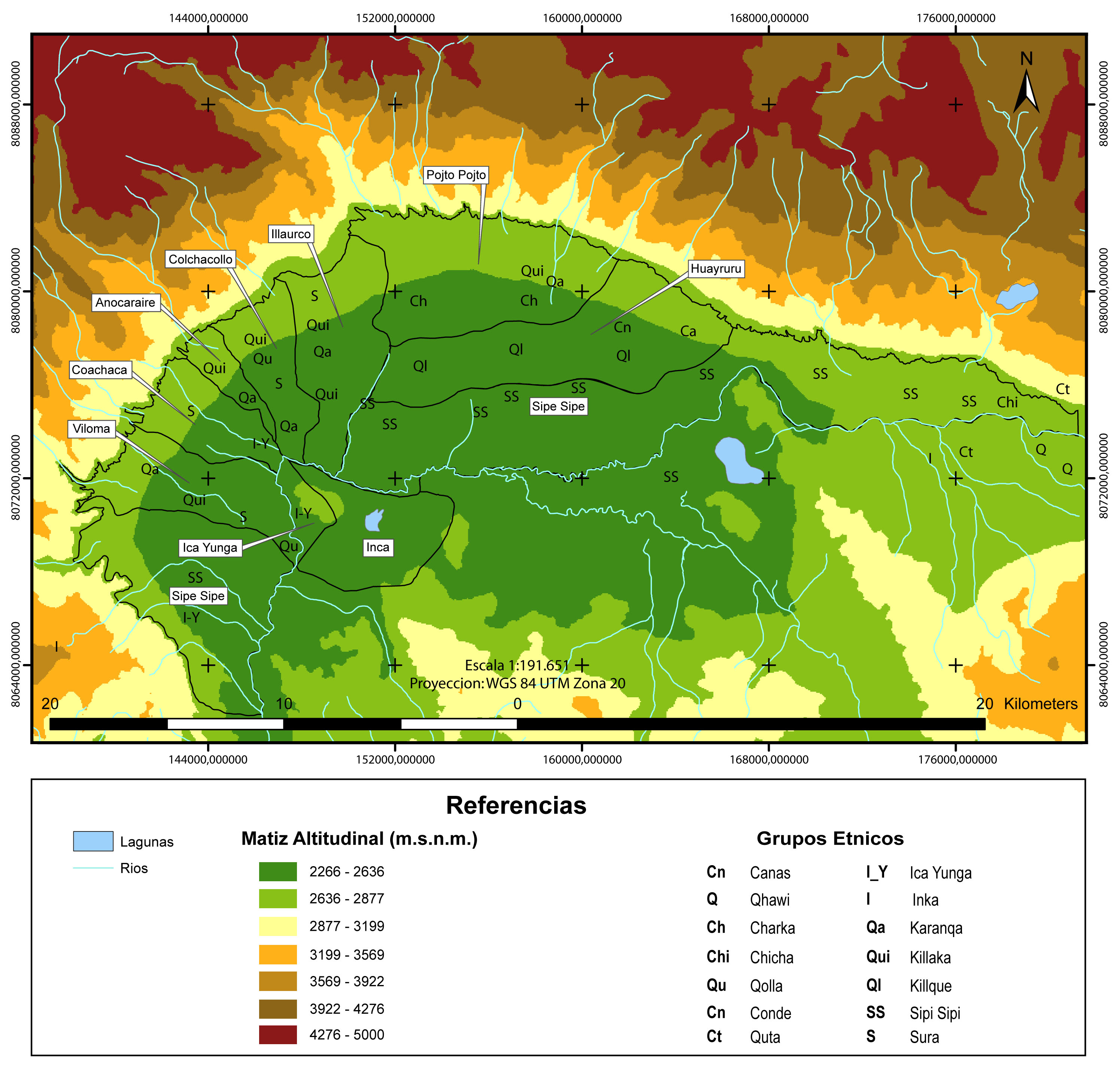

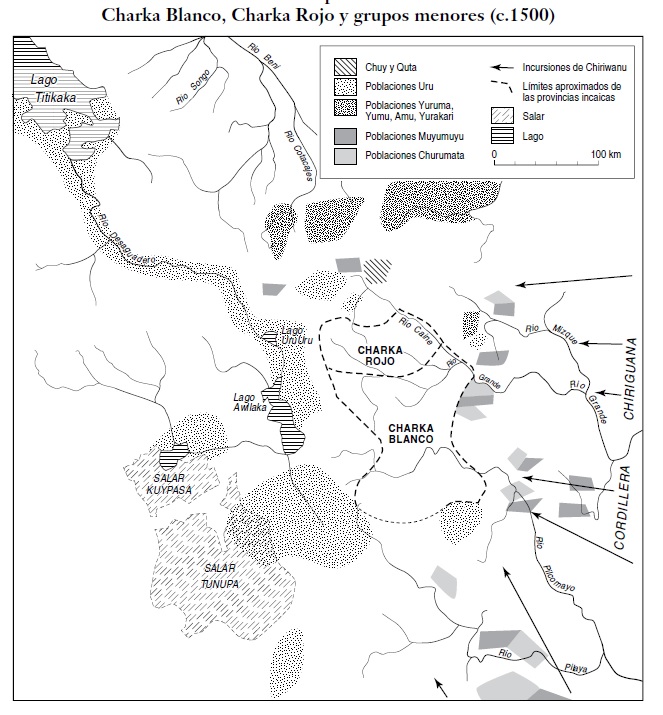

In the late 1400s, Sapa Inca Tupaq Yupanki (the Inca head of state) conquered the valleys of Cochabamba. The main native groups encountered in the Central and Upper valleys were the Sipesipes (or Sipi-Sipis), the Cotas (or Qutas), and the Chuyes (or Chuis). In an effort to consolidate Inca state control over these newly acquired territories, Tupaq Yupanki transferred part of the autochthonous population further southeast, where they were to guard the new eastern borders (see THE EASTERN BORDERS OF THE QULLASUYU - SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF THE INCA STATE - 16th CENTURY ) against the indomitable lowland chiefdoms of the Chiriguano (a name the Incas, and later the Spanish, used to refer to the Tupí-Guaraní people). While the Sipi-Sipis were mostly allowed to remain, large segments of the Quta and Chui populations were relocated to Inca fortresses in Pocona and Mizque along the eastern frontier.

Larger agrarian transformations occurred in the early 1500s, when Tupaq Yupanki’s son, Wayna Qhapaq, seized these valleys to “set up a state-owned ‘archipelago’ for the purpose of large-scale maize production, essentially for the use of the army.”3 The labor force for this vast enterprise was recruited from other areas of the Qullasuyu, mainly from the high-plateau Aymara polities (see AYMARA POLITIES of THE QULLASUYU in the 16th CENTURY ). According to testimonies recorded in colonial documents, 14,000 “Indians” were brought from “different nations,” and this figure, if accurate, indicates, “an undertaking of an unprecedented scope.”4 This contrasts sharply with other instances of state-owned archipelagos, which typically involved the resettlement of only 1,000 to 2,000 heads of household.5 Although data on the regional origins of these individuals is scarce and inconclusive, it seems certain that the 14,000 included both mitmaqkuna (people permanently resettled in the valley) and mitayos (people who rotated annually as part of the Inca labor tax system known as mit’a).

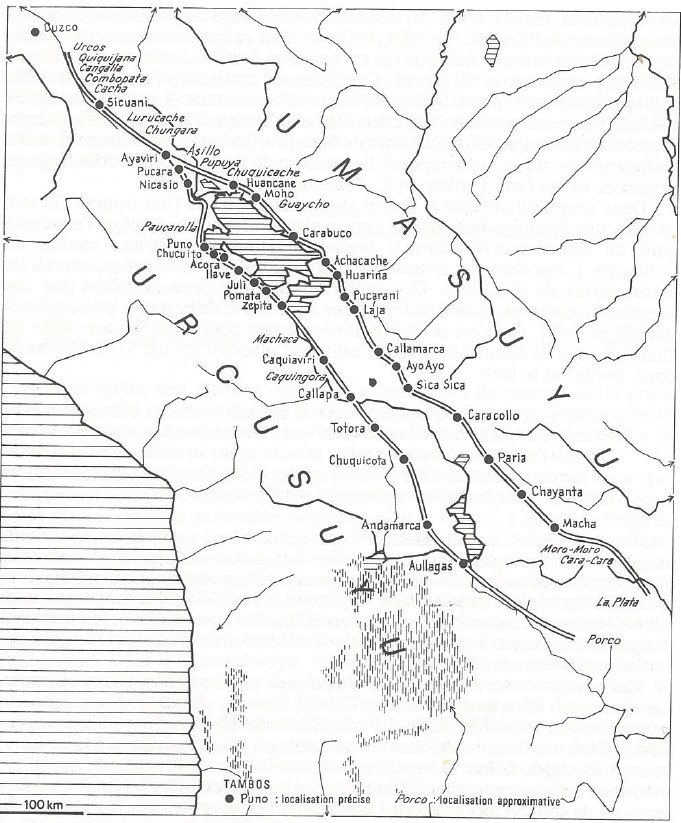

With the exception of a few small areas owned personally by Wayna Qhapaq, the lands seized in Cochabamba became part of the state domain. All fields were farmed by the mitmaqkuna and rotating mitayos, who were managed by their respective ethnic authorities, but they ultimately remained under the authority of two Inca governors. Workers were allotted certain fields for their own sustenance and were also permitted to farm the upper and lower margins of the Inca State fields. Some land was also given to ethnic authorities who were expected to practice “generosity” by redistributing the yields among those who cultivated it. Resettled mitmaqkuna and rotating mitayos also benefited from the Sapa Inca’s “generosity” and received maize from the Sapa Inca’s granaries. Apart from these redistributions, the maize produced in Cochabamba was collected at the storage center of Paria (situated on the high plateau along the Inca Road (see INCA ROADS AND TAMBOS in the 16th CENTURY )) and then transported to Cusco. The llama herders of the Suras (or Soras) (see THE AYMARA LORDSHIP OF THE SURAS IN THE 16TH CENTURY ) of Sipe-Sipe managed the transportation between the Cochabamba valleys and Paria and tended the herds belonging to the Inca State in Sipe-Sipe, located in the Lower Valley (see ).

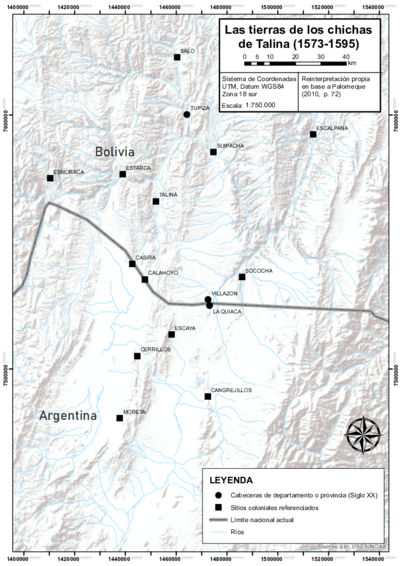

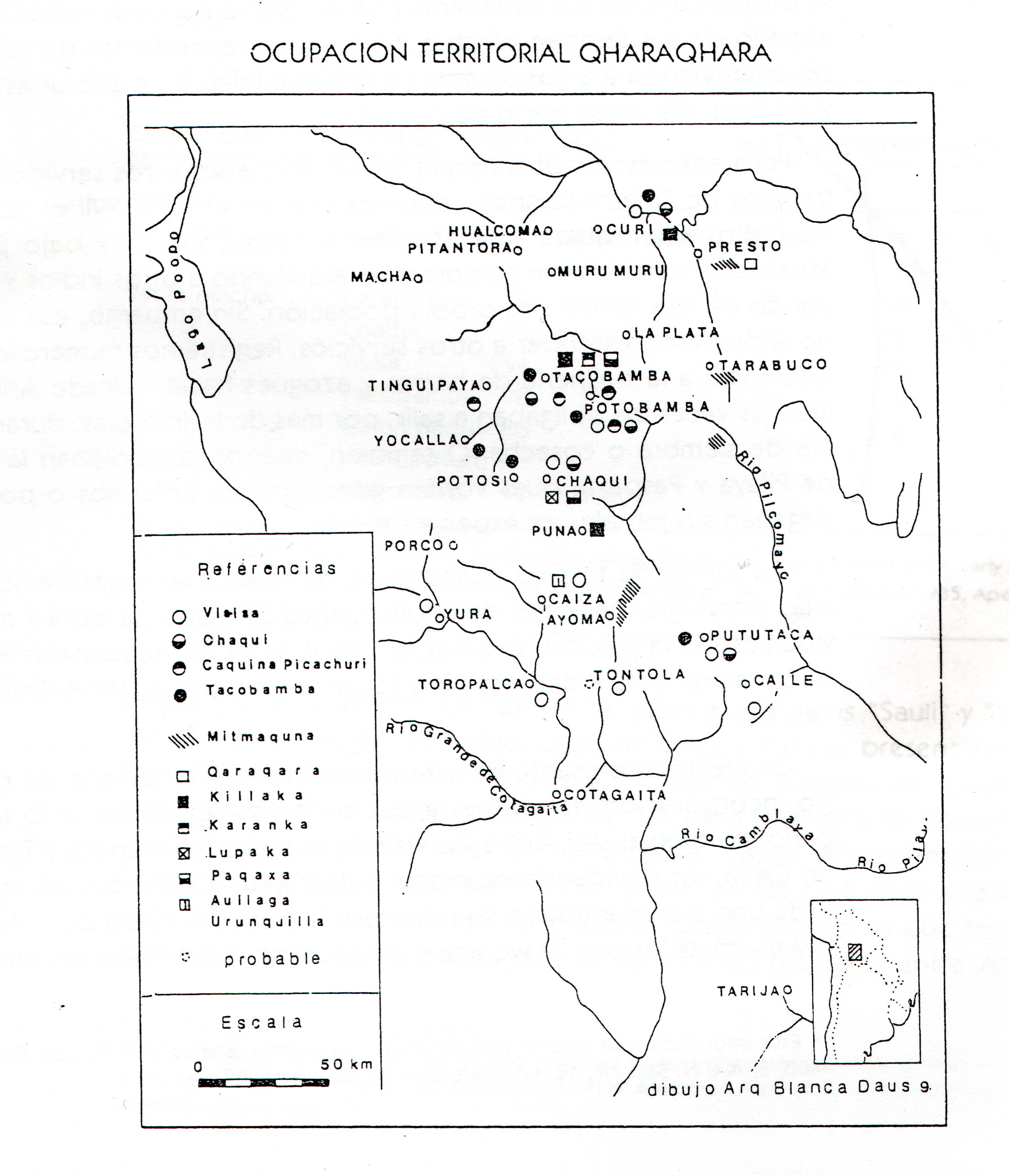

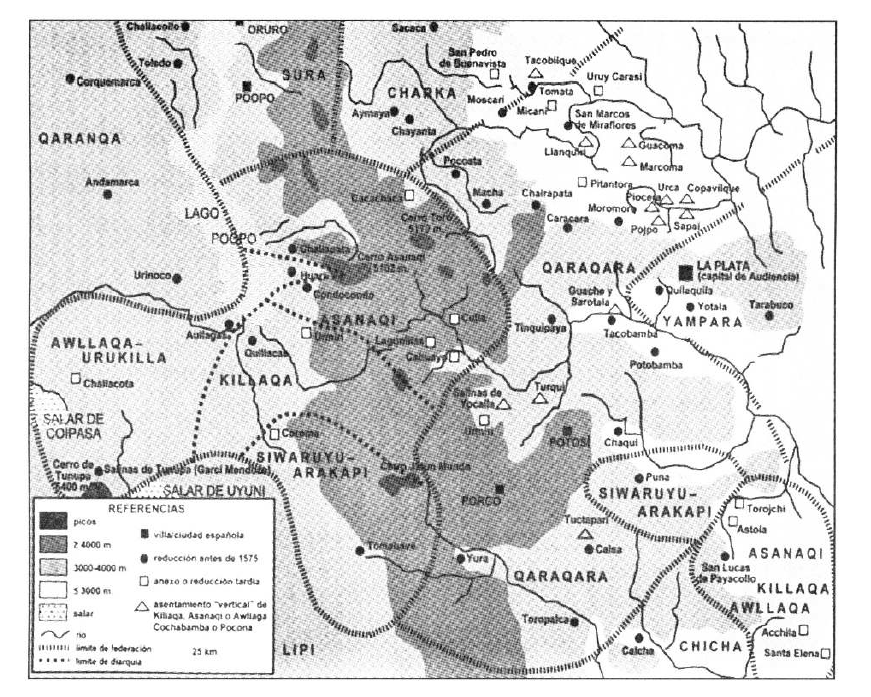

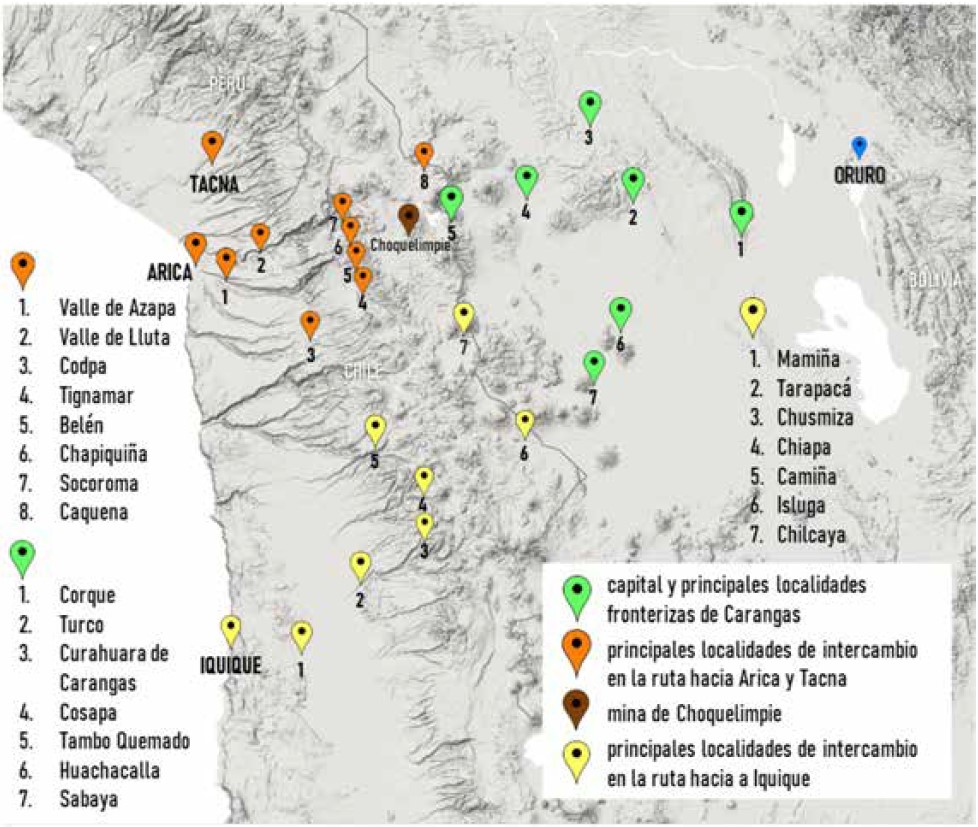

The Aymara polities rewarded with maize-cultivating colonies in the valleys of Cochabamba included the: Charkas (see AYMARA LORDSHIPS OF THE CHARKA AND NEIGHBORING NON-AYMARA POLITIES IN THE LATE 15th AND EARLY 16th CENTURIES ), Qaraqaras (see TERRITORY OF THE AYMARA LORDSHIP OF THE QARAQARA IN THE 16TH CENTURY ), Suras (see THE AYMARA LORDSHIP OF THE SURAS IN THE 16TH CENTURY ), Killakas (see TERRITORY OF THE AYMARA LORDSHIP OF THE KILLAKAS IN THE EARLY 16TH CENTURY ), Karanqas (see THE KARANQAS AYMARA POLITY - SNAPSHOT OF TRANS-BORDER CONNECTIONS AROUND 1900 (GOOGLE EARTH ADAPTATION) ), Chichas (see THE LANDS OF THE AYMARA LORDSHIP OF THE CHICHAS DE TALINA UNDER COLONIAL RULE IN THE LATE 16TH CENTURY ), Qullas, and Kanas (the Spanish spelling of these names in colonial documents and beyond is: Charcas, Caracaras, Soras, Quillacas, Carangas, Chichas, Collas, and Canas). The Urus—a non-Aymara ethnic group native to the high plateau—also had colonies in these valleys.

After the Spanish conquest, some Aymara mitmaqkunas and mitayos stationed in the valley territories returned to their homelands on the high plateau, potentially facing challenges such as property loss or diminished influence compared to their pre-conquest status. Some who remained in the valley managed to retain ties to their respective Aymara polities, while others did not. Over time, the majority of the Indigenous population of the valleys became Indigenous peasants subjected to the regime imposed by the owners of haciendas (large, privately owned estates).

In the current context of the Plurinational State of Bolivia, most of the Indigenous residents of the valleys of Cochabamba are Qhishwa speakers who generally identify as members of the Qhishwa (or Quechua) Nation.

REFERENCES:

Larson, Brooke. Colonialism and Agrarian Transformation in Bolivia: Cochabamba 1550–1900. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988.

Sánchez, Walter. “‘Indios buenos para la guerra’: Agencia (agency) local y presencia Inka en los valles de Cochabamba.” In Ocupación Inka y dinámicas regionales en los Andes (siglos XV–XVII), edited by Claudia Rivera Casanovas, 99–122. La Paz: IFEA and Plural editores, 2014.

Wachtel, Nathan. “The Mitimas of the Cochabamba Valley: The Colonization Policy of Huayna Capac.” In The Inca and Aztec States, 1400-1800: Anthropology and History, edited by George A. Collier, Renato I. Rosaldo, and John D. Wirth, 199–235. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press, 1982.

Walter Sánchez, “‘Indios buenos para la guerra’: Agencia (agency) local y presencia Inka en los valles de Cochabamba,” in Ocupación Inka y dinámicas regionales en los Andes (siglos XV–XVII), ed. Claudia Rivera Casanovas (La Paz: IFEA and Plural editores, 2014), 99–122. ↩︎

Brooke Larson, Colonialism and Agrarian Transformation in Bolivia: Cochabamba, 1550–1900. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988), 20. ↩︎

Nathan Wachtel, “The Mitimas of the Cochabamba Valley: The Colonization Policy of Huayna Capac,” in The Inca and Aztec States, 1400–1800: Anthropology and History, ed. George A. Collier, Renato I. Rosaldo, and John D. Wirth (Cambridge, MA: Academic Press, 1982), 199–235. ↩︎

Wachtel, “The Mitimas of the Cochabamba Valley: The Colonization Policy of Huayna Capac,” 218. ↩︎

Wachtel, “The Mitimas of the Cochabamba Valley: The Colonization Policy of Huayna Capac.” ↩︎