Abstract

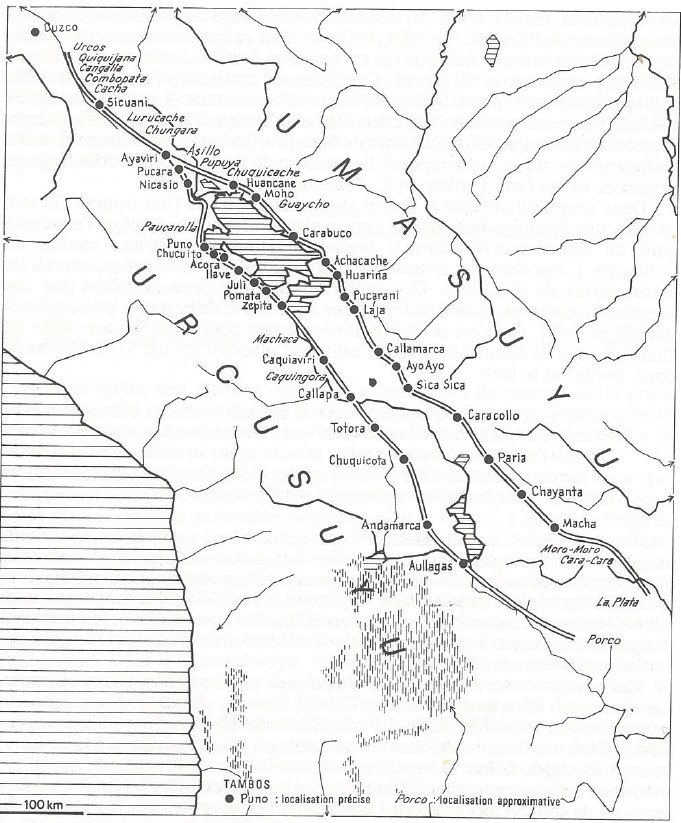

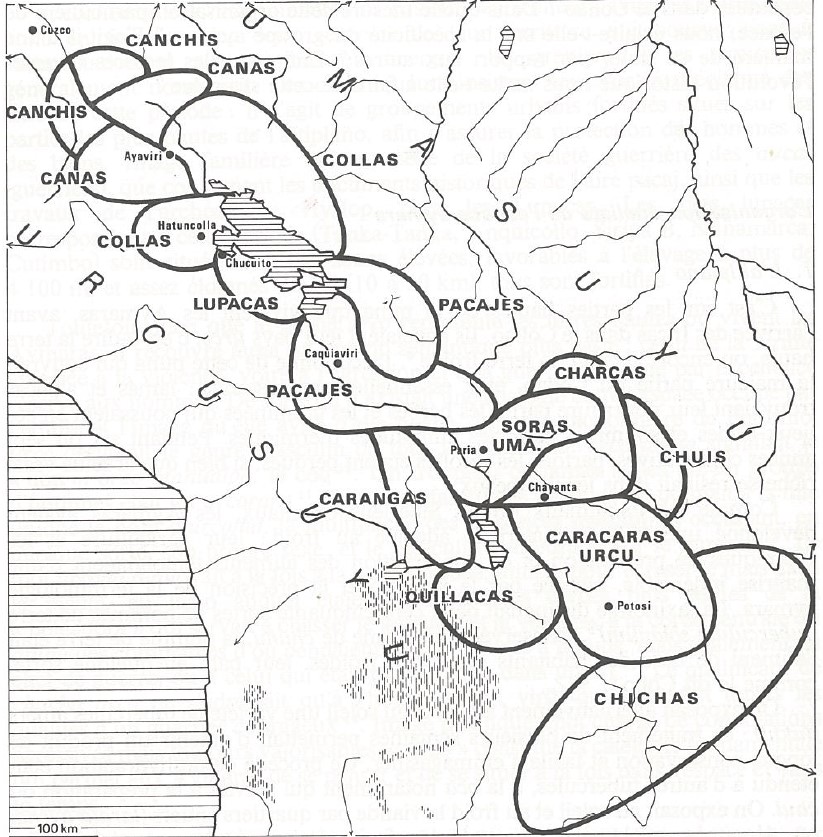

This map, drawn over the map of the Qullasuyu (see THE QULLASUYU IN THE 1530s – SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF THE INCA STATE ) and that of the Aymara polities (see AYMARA POLITIES of THE QULLASUYU in the 16th CENTURY ) located therein, depicts the high plateau region surrounding Lake Titicaca and the main Inca Road, known as Qhapaq Ñan in Qhishwa, the language of the Incas. This extensive network of roads and trails connected Cusco to the southern district of the Inca State, i.e., the Tawantinsuyu (see THE TAWANTINSUYU IN THE 1530s – TERRITORY OF THE INCA STATE ).1 The primary purpose of the Qhapaq Ñan was to facilitate communication between administrative and storage centers called tambo, and to enable the transportation and movement of armies, goods, and people. It played a crucial role in the administration and control of the vast territories under Inca rule.

Starting in Cusco, the road splits into two branches before reaching Lake Titicaca. One branch follows the western side of the lake, traversing the upper part (Urcusuyu) of the high plateau. The other branch runs along the eastern side of the lake, passing through the lower part (Umasuyu) of the high plateau. Dots on the map indicate the primary administrative and storage/granary centers of the Inca State. The word “tambo” in Qhishwa refers to a storage and redistribution center, a term still used today to denote wholesale markets. These administrative centers, established by the Incas, also served as the main centers or core settlements of the Aymara polities, sometimes requiring the relocation of pre-Inca settlements to new locations along the road.

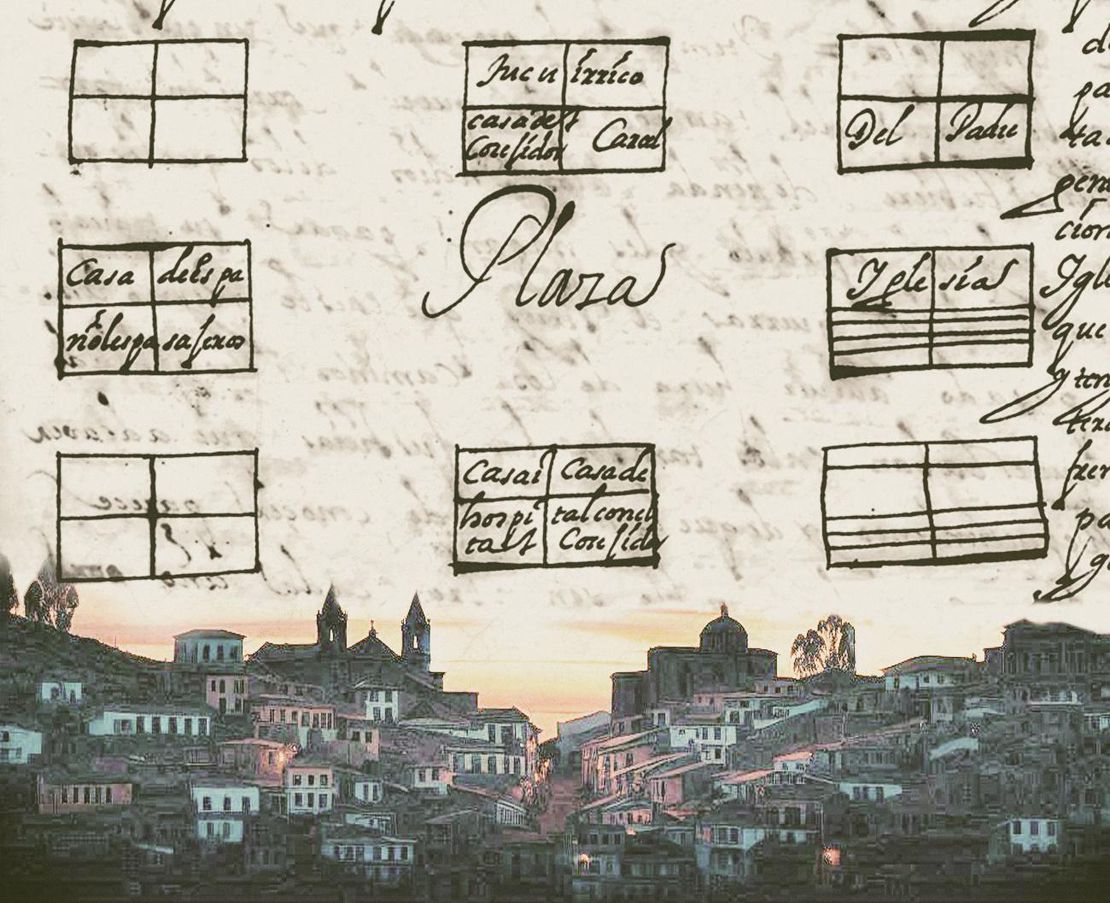

Under Spanish colonial rule, most of these administrative centers were transformed into “Indian Royal Towns” (Pueblos Reales de Indios) or reducciones. The well-maintained and strategically placed roads of the Qhapaq Ñan provided the Spanish with crucial logistical support during their military campaigns, enabling their armies to conquer the territory of the Qullasuyu. The roads, designed to connect major administrative and population centers, allowed the Spanish conquerors to strike at key locations and maintain control over vast areas.

REFERENCE:

Bouysse-Cassagne, Thérèse. “L’espace aymara: urco et uma.” Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales 33, no. 5–6 (December 1978): 1057–80. https://doi.org/10.3406/ahess.1978.294000.

Thérèse Bouysse-Cassagne, “L’espace aymara: urco et uma.” Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales 33, no. 5–6 (December 1978): 1057–80. ↩︎