Abstract

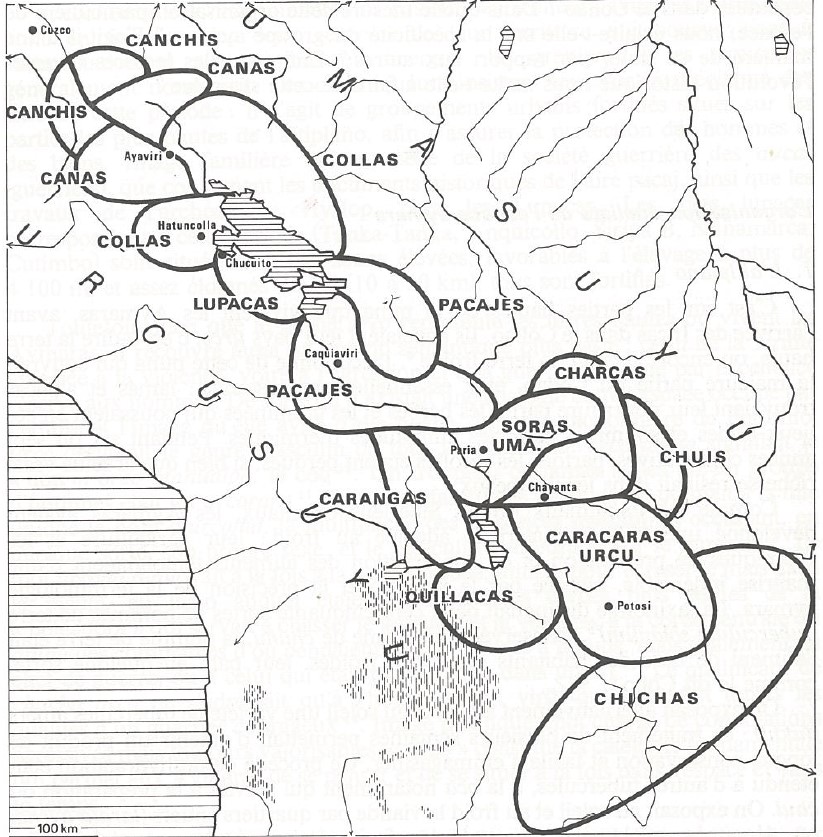

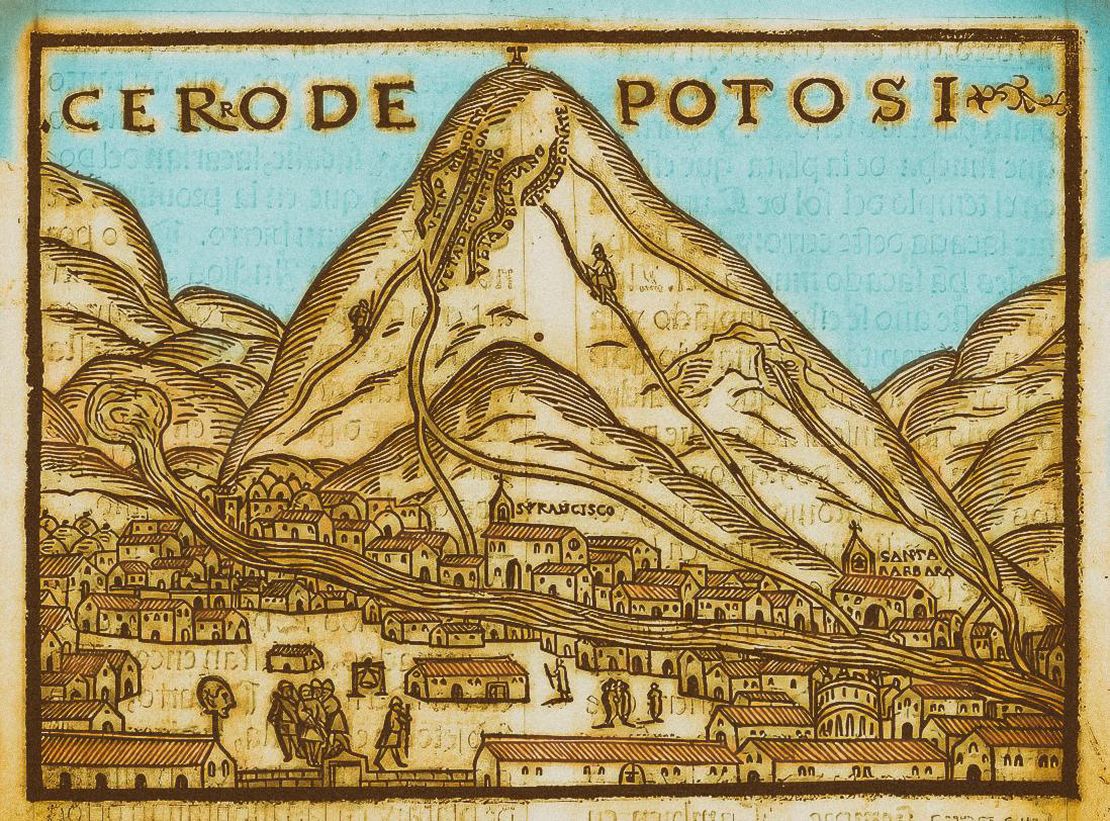

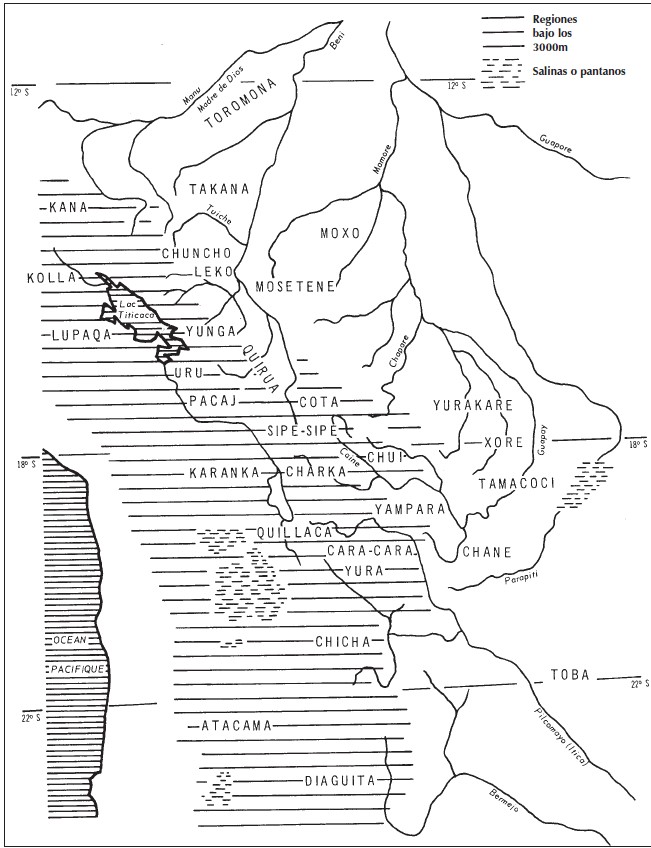

This map, which was drawn based on a list of tributaries1 found in a 1585 colonial document, shows the Aymara polities that were established by Spanish colonial authorities as tributary units in the late 16th century.2 These tributaries, called mitayos, were part of a draft labor system known as mita (see COLONIAL LEGISLATIONS AS A FRAMEWORK FOR DISPOSSESSIONS IN THE CENTRAL ANDES: THE COLONIAL MITA ), under which populations from these polities were required to provide laborers to work in the mines of Potosí. At that time, the area covered by these colonial tributary units roughly corresponded to the territories of pre-colonial Aymara polities in the Qullasuyu (see THE QULLASUYU IN THE 1530s – SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF THE INCA STATE ), i.e., the southern district of the Tawantinsuyu (see THE TAWANTINSUYU IN THE 1530s – TERRITORY OF THE INCA STATE ).3 This map also depicts the division of the high plateau into two halves: the Urcusuyu (upper area) and the Umasuyu (lower area), reflecting the dualistic Andean worldview in which space is composed of two opposing yet complementary parts (upper and lower) united by a central point, or taypi—in this case, Lake Titicaca. The term urcu has masculine, dominant, and phallic connotations, while uma is associated with femininity, valleys, and water. In accordance with this mode of thought, the territories of Aymara polities were organized into two sections: the upper moiety and the lower moiety.

While the core settlements of these Aymara polities were located in the cold lands of the high plateau, the territories they controlled included a series of “islands” at different altitudes descending into the western and eastern valleys, thus forming “vertical archipelagos.”4 As described by Larson, “the ‘archipelago’ pattern of territoriality (…) required kinsmen to trek many days through diverse landscape and ‘foreign’ territory to their outlying colonies.”5 This economy of vertical control and reciprocal exchanges across different ecological tiers was rooted in a socio-political structure governed by kinship bonds. This framework of kinship provided the language that legitimated a complex amalgam of both communal and stratified social structures, which in turn ensured the cohesion and unity of kin groups scattered across the polities’ discontinuous territories.

Aymara polities were formed by “confederated lineages” or, more precisely, sets of nested kin groupings called ayllus. In both Qhishwa (the language of the Incas) and Aymara, the word ayllu can be translated as “grouping” or “lineage” and refers to kinship-based social structures of varying sizes and complexities. At its smallest scale, a “minimal” ayllu consisted of an extended network of households, forming the basic unit of pre-colonial Andean societies. A variable number of minimal ayllus would combine to form a “minor” ayllu, multiple minor ayllus together formed a “major” ayllu or moiety, and two major ayllus constituted a “maximal” ayllu.6

The nested structure of the ayllus was also reflected in their spatial organization. Thus, the territory of the maximal ayllus was divided into an upper and lower half, corresponding to the upper and lower moieties, and this same principle applied to the organization of space in major, minor, and minimal ayllus. Furthermore, each moiety held land across different ecological tiers, as did the minor and minimal ayllus. Although the terms “kingdom” and “lordship” are frequently used to describe these pre-Columbian Aymara polities, the term “diarchy” might be more accurate, as there is no clear evidence of a single higher authority governing both moieties in pre-colonial times.7

Ayllu membership conferred common rights to land, which probably implied a collective form of land tenure. However, there is also evidence that chiefs, nobles, and elders held land independently of the ayllus and were able to mobilize labor and extract surplus from the ayllu members they governed, suggesting an “incipient class structure.”8 This complex socio-political and economic system also involved sending ayllu members to farm in the lower-altitude “islands” located in temperate and sub-tropical valleys. “Called mitmaqkuna, these highland colonists were the vital link binding the interregional and multi-ecological economy that was so crucial in maintaining highland population.”9 The principle of shared descent that underpinned ayllu membership provided cohesion to this vertical economy across the discontinuous territories of “vertical archipelagos.”10

Within the complex, nested structure of the ayllus, authority was vested in an elaborate hierarchy of chieftains, lords of moieties, and regional chiefs who represented the unity, common interests, and identity of the group. These leaders were expected to uphold certain standards of justice and equity but also had the power to mobilize ayllu members for various purposes, including personal services, collective works, and warfare. The social stratification of Aymara society meant that reciprocal exchanges between ayllu members were often asymmetrical in nature; however, their socio-political organization was nevertheless governed by the ideals and idioms of reciprocity. Thus, “while Andean societies may have been marred by social differentiation and accumulative processes, the normative order mandated a degree of social control that placed structural limits on the exploitation of the poorer peasants. The dominant ideology thus blunted the cutting edge of class formation based on property relations.”11

Despite controversial debates concerning the origins of the Aymara people, archaeological and linguistic research suggests that different waves of Aymara speakers from central-south Peru migrated further south from 200 AD onwards and consolidated their core settlements on the high plateau between the 1000s and 1400s AD.12 Little is known about the kinds of relations they established with other ethnic groups that inhabited the high plateau. What we do know is that during the process of Inca expansion southwards, Aymara polities were major rivals to the Incas and were only subdued after prolonged struggles. Once integrated into the Inca State (in the late 1400s) as respected allies and warriors, they made substantial contributions to the expansion of the Inca State’s eastern and southern borders (see THE EASTERN BORDERS OF THE QULLASUYU - SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF THE INCA STATE - 16th CENTURY ). In return, Aymara polities were granted tracts of valley farmland for maize cultivation, exemptions from certain tribute obligations, and, most importantly, the ability to retain a significant degree of autonomy under indirect Inca rule. In these ways the Inca State consolidated and solidified the hegemony of Aymara polities and their authority over the territories they shared with the Urus, Pukinas, and other ethnic groups.

By the time Spanish conquerors arrived in the Qullasuyu in the 1530s, many Urukilla and Pukina speakers lived as minority groups in territories controlled by powerful Aymara authorities. According to a general census from the 1570s, Aymara speakers constituted 70% of the Indigenous population of the high plateau.13 It was with these powerful authorities that the colonial state “negotiated” the organization of colonial tributary units, imposing on them the responsibility of recruiting the required number of draft laborers for Potosí’s silver mines. This information, along with a list of tributary units registered in 16th-century colonial documents, allowed 20th-century ethnohistorians to roughly estimate the location of the Aymara polities shown on the map.

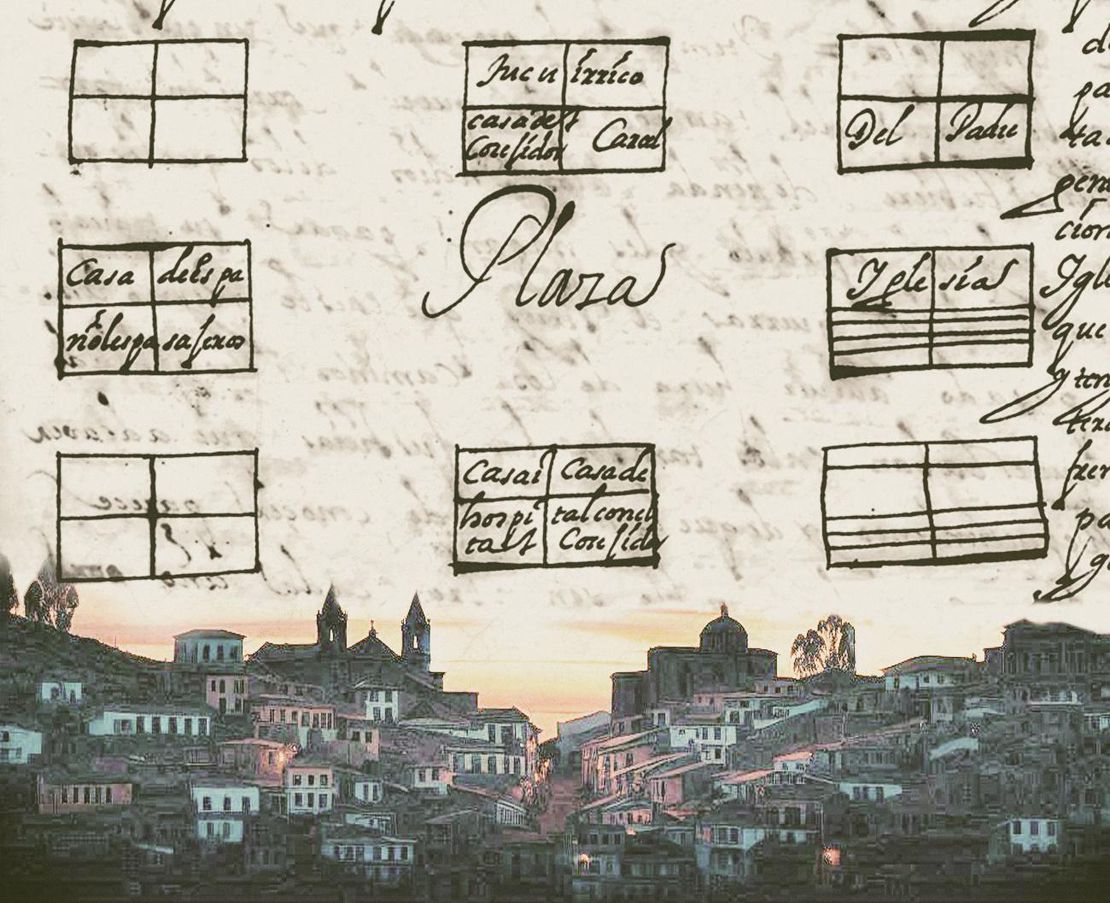

The organizational structure of these large Aymara diarchies and the shape and composition of their discontinuous territories were dramatically altered under Spanish colonial rule. Through massive forced resettlement policies, the populations of scattered hamlets were congregated into centralized, nucleated towns called reducciones or “Pueblos Reales de Indios”, under the watchful gaze of colonial administrators. This reducción congregation process led to a radical transformation of Aymara society, which involved a complete reconfiguration of traditional spatial organization, the disruption of macro-vertical control of ecological niches, the dismantling and fragmentation of the large Aymara diarchies into a multiplicity of smaller “Indian communities.” Although these “Indian communities” on the high plateau were given access to land and were able to reconstruct elements of the ayllu structure and vertical control on a much smaller scale, they were ultimately integrated into colonial society as a source of labor and surplus extraction.

REFERENCES:

Abercrombie, Thomas. Pathways of Memory and Power: Ethnography and History among an Andean People. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1998.

Bouysse-Cassagne, Thérèse. “L’espace aymara: urco et uma.” Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales 33, no. 5–6 (December 1978): 1057–80. https://doi.org/10.3406/ahess.1978.294000.

Bouysse-Cassagne, Thérèse. La identidad aymara: Aproximación histórica (siglo XV, Siglo XVI). Lima: Instituto Francés de Estudios Andinos, 2015.

Bouysse-Cassagne, Thérèse. “Pertenencia étnica, status económico y lenguas en Charcas a fines del siglo XVI.” In Tasa de la visita general de Francisco de Toledo, edited by Noble David Cook, 312–328. Lima: Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, 1975.

Bouysse-Cassagne, Thérèse. “Apuntes para la historia de los puquina hablantes.” Boletín de Arqueología PUCP no. 14 (2010): 283–307.

Cerrón-Palomino, Rodolfo. El origen centro andino del aimara.” Boletín de Arqueología PUCP no. 4 (2000): 131–142.

Cook, Noble David, ed. Tasa de la visita general de Francisco de Toledo. Lima: Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, 1975.

Klein, Herbert. Fiscalidad real y gastos de gobierno: El Virreinato del Perú, 1680–1809. Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, 1994.

Larson, Brooke. Colonialism and Agrarian Transformation in Bolivia: Cochabamba, 1550–1900. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988.

Murra, John V. Formaciones económicas y políticas del mundo andino. Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, 1975.

Platt, Tristan. “Mirrors and Maize: The Concept of Yanantin among the Macha of Bolivia.” In Anthropological History of Andean Polities, edited by John V. Murra, Nathan Wachtel, and Jacques Revel, 228–259. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986.

Saignes, Thierry. “De la filiation à la résidence.” Annales ESC 33, no. 5–6 (1978): 1160–1181.

Torero, Alfredo. “Lenguas y pueblos altiplánicos en torno al siglo XVI.” Revista Andina 10, no. 2 (1987): 329–372.

“Tributaries” (tributarios in Spanish) were Indigenous individuals or communities subjected to colonial tribute obligations as part of the colonial tax system, providing goods, labor, or payments to the Spanish Crown. “Tributary units” were administrative divisions created to manage and organize these tribute collections. ↩︎

Thérèse Bouysse-Cassagne, “L’espace aymara: urco et uma,” Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales 33, no. 5–6 (December 1978): 1057–80. ↩︎

Bouysse-Cassagne, “L’espace aymara: urco et uma,”1057–80. ↩︎

John Murra, Formaciones económicas y políticas del mundo andino (Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, 1975). ↩︎

Brooke Larson, Colonialism and Agrarian Transformation in Bolivia: Cochabamba, 1550–1900 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988), 20. ↩︎

Tristan Platt, “Mirrors and Maize: The Concept of Yanantin among the Macha of Bolivia,” in Anthropological History of Andean Polities, ed. John V. Murra, Nathan Wachtel, and Jacques Revel (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986), 228–259. ↩︎

Thomas Abercrombie, Pathways of Memory and Power: Ethnography and History among an Andean People (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1998). ↩︎

Herbert Klein, Fiscalidad real y gastos de gobierno: El Virreinato del Perú, 1680–1809 (Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, 1994). ↩︎

Klein, Fiscalidad real y gastos de gobierno: El Virreinato del Perú, 1680–1809. ↩︎

Thierry Saignes, “De la filiation à la résidence,” Annales ESC 33, no. 5–6 (1978): 1160–1181. ↩︎

Larson, Colonialism and Agrarian Transformation in Bolivia: Cochabamba, 1550–1900, 25. ↩︎

Alfredo Torero, “Lenguas y pueblos altiplánicos en torno al siglo XVI,” Revista Andina 10 no. 2 (1987): 329–372; Rodolfo Cerrón-Palomino, “El origen centro andino del aimara,” Boletín de Arqueología PUCP No. 4 (2000): 131–142; Thérèse Bouysse-Cassagne, “Apuntes para la historia de los puquina hablantes,” Boletín de Arqueología PUCP No. 14 (2010): 283–307. ↩︎

Bouysse-Cassagne, “Pertenencia étnica, status económico y lenguas en Charcas a fines del siglo XVI,” in Tasa de la visita general de Francisco de Toledo, ed. Noble David Cook, (Lima: Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, 1975), 312–328; Noble David Cook, Tasa de la visita general de Francisco de Toledo (Lima: Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, 1975). ↩︎