Abstract

Layered over a Google Earth map and drawing from historical and archaeological data, this map shows a rough approximation of the territory of the Qullasuyu, i.e., the southern district of the Tawantinsuyu (see THE TAWANTINSUYU IN THE 1530s – TERRITORY OF THE INCA STATE ) or Inca State, at the time of the Spanish conquest.1 This large district encompassed what is now southern Peru, the highlands of Bolivia, and the northern territories of Chile and Argentina. The eastern borders (see THE EASTERN BORDERS OF THE QULLASUYU - SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF THE INCA STATE - 16th CENTURY ) with the Amazonian Basin and the Chaco Region were porous and unstable. The Qullasuyu included the large high plateau where Lake Titicaca is located, the inter-Andean valleys to the east, and the valleys and coastal lands to the west. The high plateau begins in southern Peru, where the Andean Mountain Range splits into two ranges (the Cordillera Oriental to the east and the Cordillera Occidental to the west), and ends in northern Argentina, where these two mountain ranges converge again.

Tracing the origins of the development of complex societies in this region back to 1200 BC, archaeologists argue that ancient, pre-Inca “Titicaca Basin states controlled or influenced peoples throughout the south-central Andes, a region that extends over 400,000 square kilometers. One of the most outstanding achievements of these Titicaca Basin polities was their ability to exploit lower ecological zones up to several hundred kilometers away. (…) By the beginning of the first millennium AD, two complex polities, known as Pukara and Tiwanaku, had developed [on] the north and south sides of the basin respectively. By AD 900, Tiwanaku had developed into a true empire that rivaled other pre-Hispanic New World states in power, organizational complexity, and territorial extent.” 2

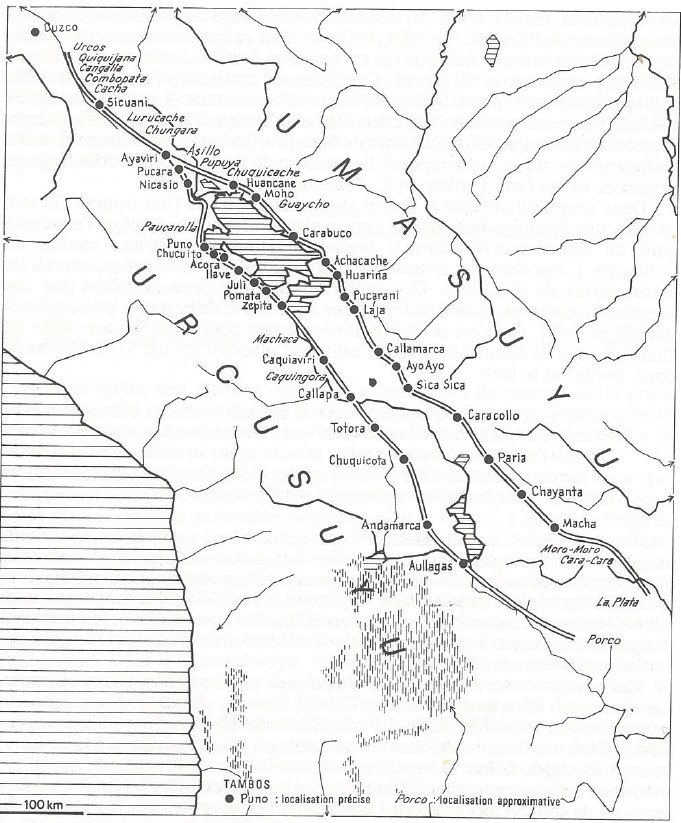

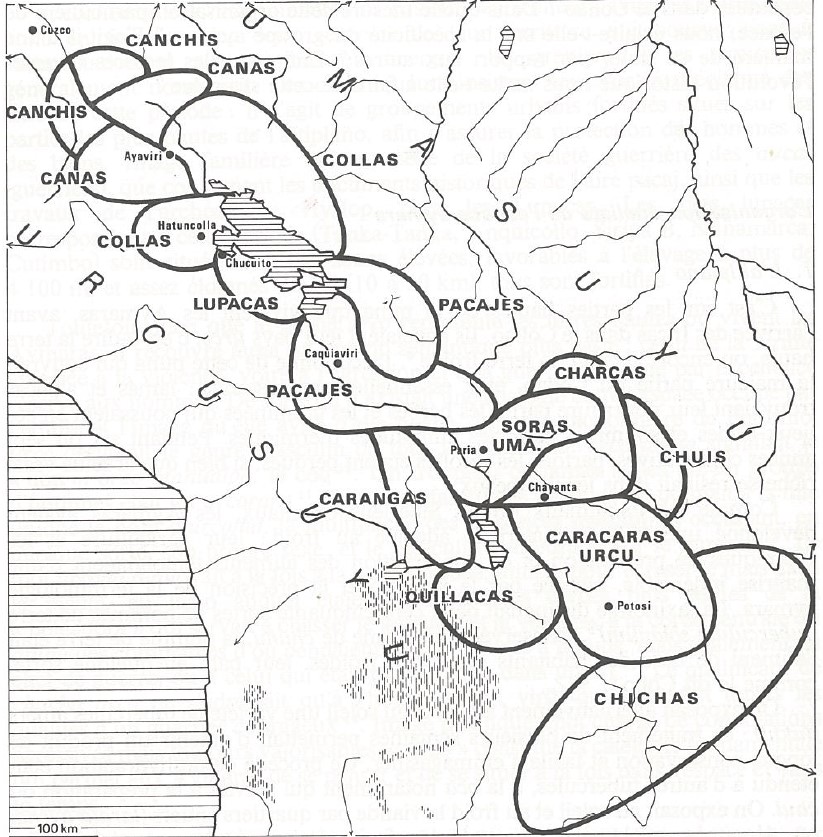

There is no consensus about what exactly happened in this vast territory after the collapse of Tiwanaku around the year 1000 AD, but it seems that by the time of the Inca expansion, starting in the 1430s, it had become a multi-ethnic and multilingual territory with a predominant presence of Urukilla-, Pukina-, and Aymara-speaking polities (see AYMARA POLITIES of THE QULLASUYU in the 16th CENTURY ) on the high plateau, and a variety of other ethnic groups in the eastern valleys. Under Inca rule, Qhishwa speakers also arrived in this region, and Qhishwa—the language of the Incas—became the lingua franca in administrative centers and areas assigned for state use. (Nowadays, the Pukina language has disappeared, but Urukilla, Aymara, and Qhishwa are still spoken in this area of the Andes.) Furthermore, the Incas integrated the territory of the Qullasuyu with a system of Inca roads (see INCA ROADS AND TAMBOS in the 16th CENTURY ). These Inca roads, known as Qhapaq Ñan, formed a sophisticated network of pathways spanning thousands of miles across the Andean region and connecting administrative and storage centers. These meticulously engineered roads facilitated communication, trade, and the movement of people and goods throughout the vast expanse of the Inca State, connecting diverse landscapes, settlements, and cultural centers.

During the Inca expansion southward, Aymara polities were major rivals to the Incas and were subdued only after prolonged military and political struggles. Once the Inca State consolidated its presence in the region, most Aymara polities became key and well-rewarded allies. In the end, through alliance policies, land rewards, and indirect rule, which guaranteed a considerable degree of autonomy, Inca rulers consolidated the hegemony of Aymara polities and the power of their authorities over the territories they shared with Urukilla and Pukina speakers.

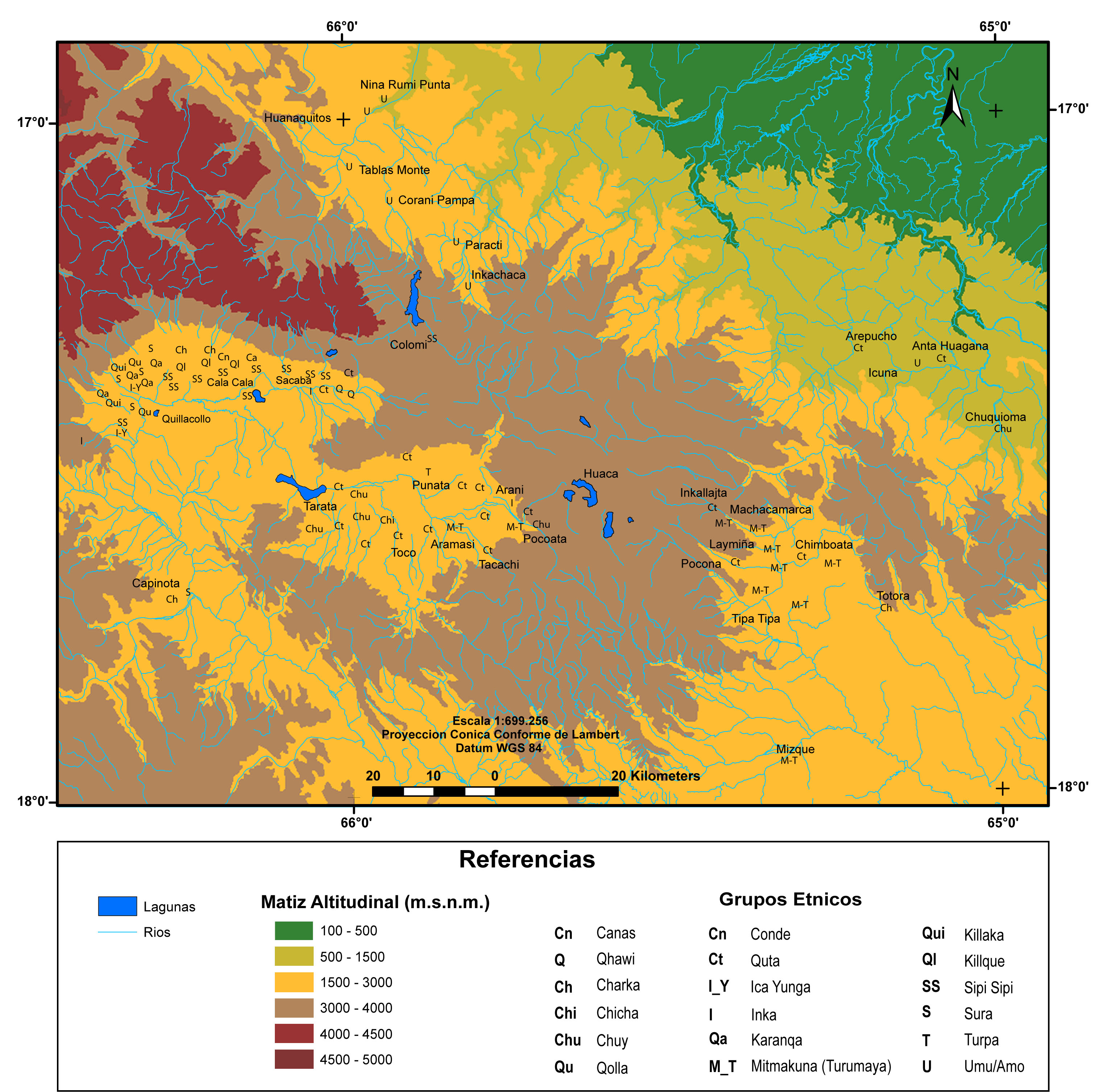

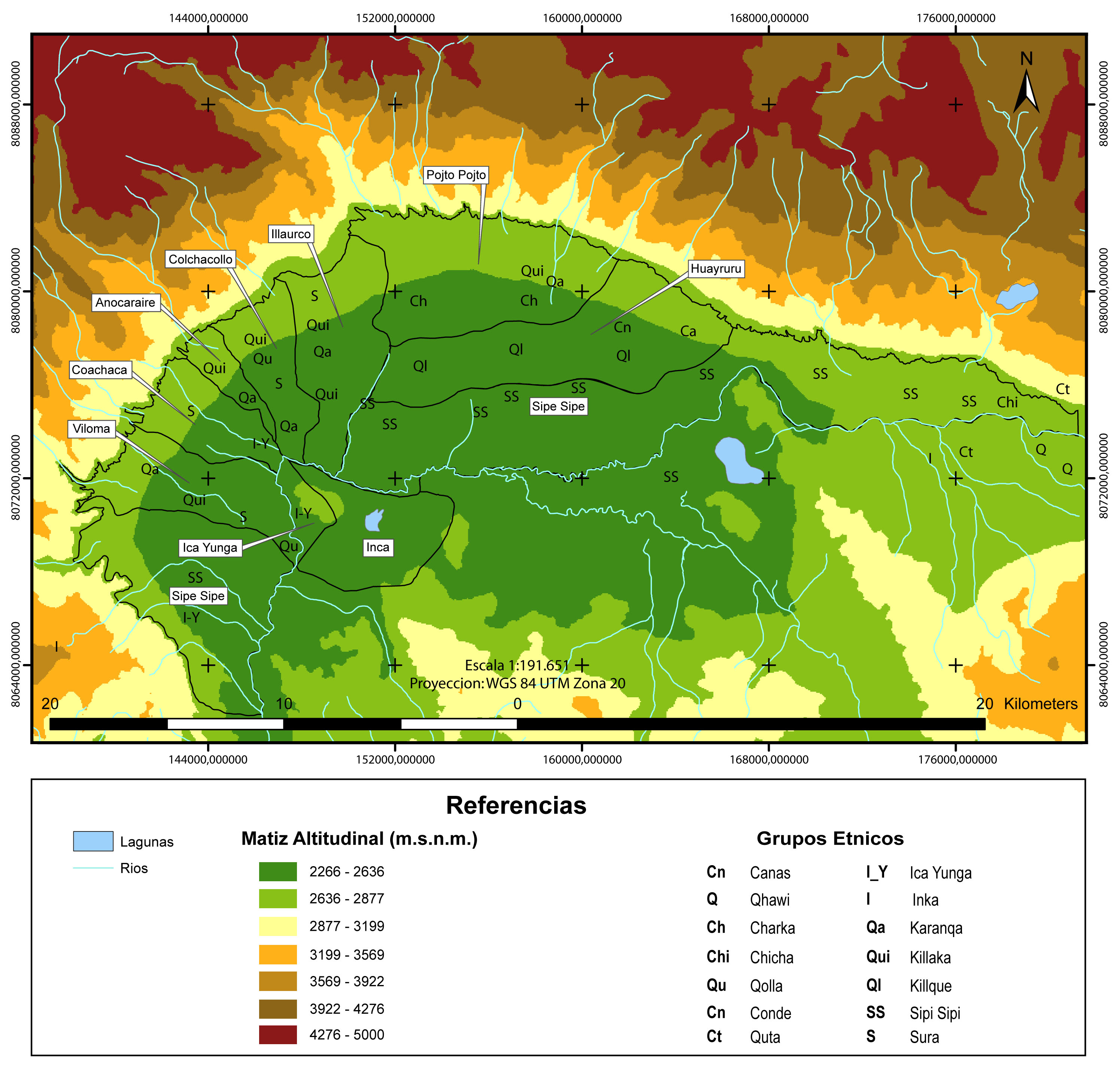

The expansion of the Inca State beyond the territories controlled by Aymara polities and further into the eastern inter-Andean valleys was of a very different kind. For example, the Incas claimed the Lower, Central, and Upper Valleys of what is today Cochabamba (in Bolivia) as Inca state domains and transferred the autochthonous population, Qutas and Chuis, further east, thus transforming the inter-Andean valleys into a multi-ethnic territory (see MULTI-ETHNIC TERRITORY under INCA DIRECT RULE: THE CENTRAL AND UPPER VALLEYS OF COCHABAMBA in the 1530s and MULTI-ETHNIC TERRITORY under INCA DIRECT RULE: THE LOWER VALLEY OF COCHABAMBA in the 1530s ). Indeed, by strategically relocating large segments of populations from different regions (and thus protecting new and unstable state eastern borders), the Incas turned these valleys into a highly diverse territory governed by Inca officials through direct rule.3 Direct rule was also applied in other areas designated for state use, such as mining centers and religious centers.

It is upon this human landscape that the European conquerors imposed the colonial rule of the Spanish crown aimed at extracting Indigenous surplus and labor force. The different models of Inca rule—direct in the valleys and indirect in the highlands—gave rise to different colonial patterns in these two areas. Over time, Spanish colonization dismantled the political and spatial organization of Aymara polities, fragmenting them into smaller, separate Indigenous communities and truncated ethnic archipelagos. Although this process disrupted and disarticulated the political economy of vertical ecological control, Andean peasants managed to recreate elements of the ayllu structure and partial models of ecological control, though their success in doing so varied significantly between the valleys and the highlands. This disparity deepened as the valleys of Cochabamba became strongholds for Spanish landowners who acquired large estates (haciendas), while the Indigenous ayllus on the high plateau—though fragmented and reconstituted—managed to maintain greater access to land, preserve communal forms of land ownership, and retain more internal autonomy than their counterparts in the valleys. Today, Indigenous communities in the valleys of Cochabamba, as well as in the southern half of the high plateau, are predominantly Qhishwa speakers and tend to identify as members of the Qhishwa (or Quechua) Nation, while Indigenous communities in the northern half of the high plateau and neighboring valleys are Aymara speakers and identify as members of the Aymara Nation.

REFERENCES:

Bouysse-Cassagne, Thérèse. La identidad Aymara: Aproximación histórica (Siglo XV, Siglo XVI). Lima: Instituto Francés de Estudios Andinos, 2015.

D’Altroy, Terence. The Incas. Hoboken, New Jersey: Blackwell, 2003.

Larson, Brooke. Colonialism and Agrarian Transformation in Bolivia: Cochabamba 19550–1900. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988.

Murra, John V. Formaciones económicas y políticas del mundo andino. Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, 1975.

Nielsen, Axel. “El Tawantinsuyu: Cosmología, economía y organización política.” In Camino ancestral Qhapaq Ñan: Una vía de integración de los Andes en Argentina, edited by Victoria Sosa, 24–52. Buenos Aires: Ministerio de Cultura de la Nación, Secretaría de Patrimonio Cultural.

Pärssinen, Martti. Tawantinsuyu: The Inca State and its Political Organization. Helsinki: Suomen Historiallinen Seura, 1992.

Stanish, Charles. Ancient Andean Political Economy. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2011.

Wachtel, Nathan. “The Mitimas of the Cochabamba Valley: The Colonization Policy of Huayna Capac.” In The Inca and Aztec States, 1400–1800: Anthropology and History, edited by George A. Collier, Renato I. Rosaldo, and John D. Wirth, 199–235. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press, 1982.

Terence D’Altroy, The Incas (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2002), 88; Axel Nielsen, “El Tawantinsuyu: Cosmología, economía y organización política,” in Camino ancestral Qhapaq Ñan: Una vía de integración de los Andes en Argentina, ed. Victoria Sosa (Buenos Aires: Ministerio de Cultura de la Nación, Secretaría de Patrimonio Cultural, 2020), 40; Martti Pärsinnen, Tawantinsuyu: The Inca State and Its Political Organization. (Helsinki: Suomen Historiallinen Seura, 1992). ↩︎

Charles Stanish, Ancient Andean Political Economy. (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2011). ↩︎

Nathan Wachtel, “The Mitimas of the Cochabamba Valley: The Colonization Policy of Huayna Capac,” in The Inca and Aztec States, 1400–1800: Anthropology and History, eds. George A. Collier, Renato I. Rosaldo, and John D. Wirth (Cambridge, MA: Academic Press, 1982), 199–235. ↩︎