Abstract

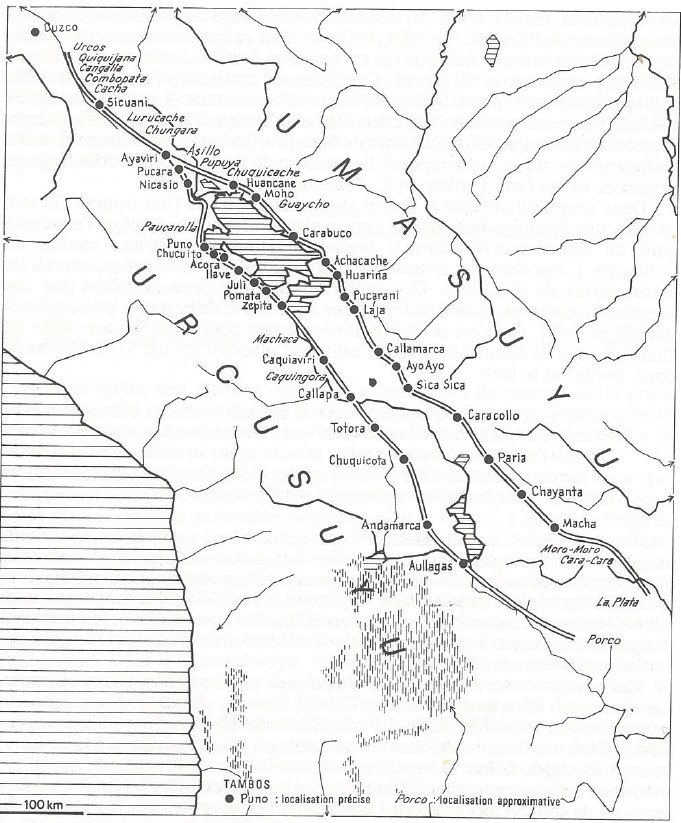

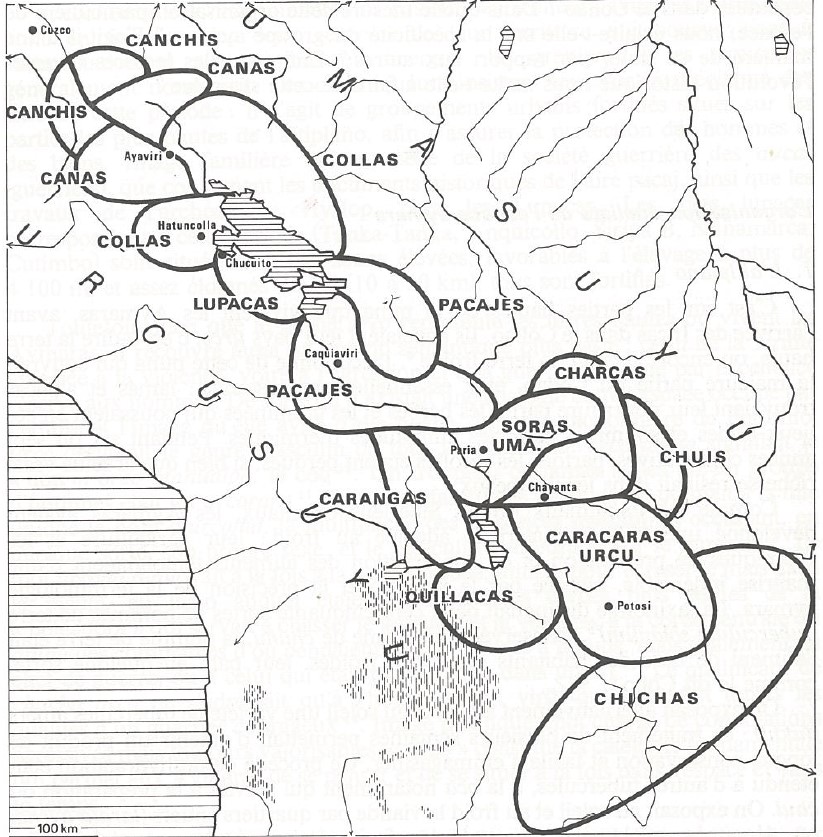

Layered over a Google Earth map and drawing from historical and archaeological data, this map offers a rough approximation of the territory of the Tawantinsuyu, i.e., the Inca State, at the time of the Spanish conquest.1 Located within the Central Andean region, this territory extended from present-day southern Colombia all the way southwards to present-day northern Argentina, encompassing the highlands of Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia, the northern region of Chile and the northwestern region of Argentina. The Inca State was divided into four large districts, or suyus (in Qhishwa, the language of the Incas still spoken in most parts of this territory, tawa means four and suyu could be translated as district or region): Cuntisuyu, Antisuyu, Chinchasuyu, and Qullasuyu (see THE QULLASUYU IN THE 1530s – SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF THE INCA STATE ). There is no consensus on the boundaries of the eastern border, which was porous and unstable, nor on the exact shape of the Antisuyu. Likewise, there is no clear agreement on the internal borders between the four suyus, although it is increasingly acknowledged that they all originated in Cusco, the main center or capital of the Inca State. This vast territory was unified by a complex system of Inca roads (see INCA ROADS AND TAMBOS in the 16th CENTURY ) connecting numerous administrative centers.

The Incas ruled over this vast multi-ethnic territory through a combination of indirect and direct rule. Often represented as a pyramid, the political-administrative organization of the state had the Sapa Inca (the Inca head of state) at the top, immediately below the prefects of the four large districts, and below them the governors who were also members of the Inca nobility. At the lower echelons of the administrative hierarchy were non-Inca local authorities, such as lords of the conquered polities and chiefs of relocated multi-ethnic groups. The Incas sought the loyalty of these local authorities through gifts, marriage, indoctrination, and privileged access to land and labor. Articulating the Inca and non-Inca levels of administration was a vast bureaucracy of inspectors, census takers, tribute collectors and other state officials who preserved the internal order and ensured that tribute obligations were met satisfactorily.

There were two kinds of labor taxes imposed by the Inca State. One, known as mit’a, consisted of a specific number of days of labor in public works, in personal service to state officials, or in the army. The other type consisted of agricultural or pastoral work in the fields or with the herds belonging to the state, the Sapa Inca, or other members of his lineage (panaqa).

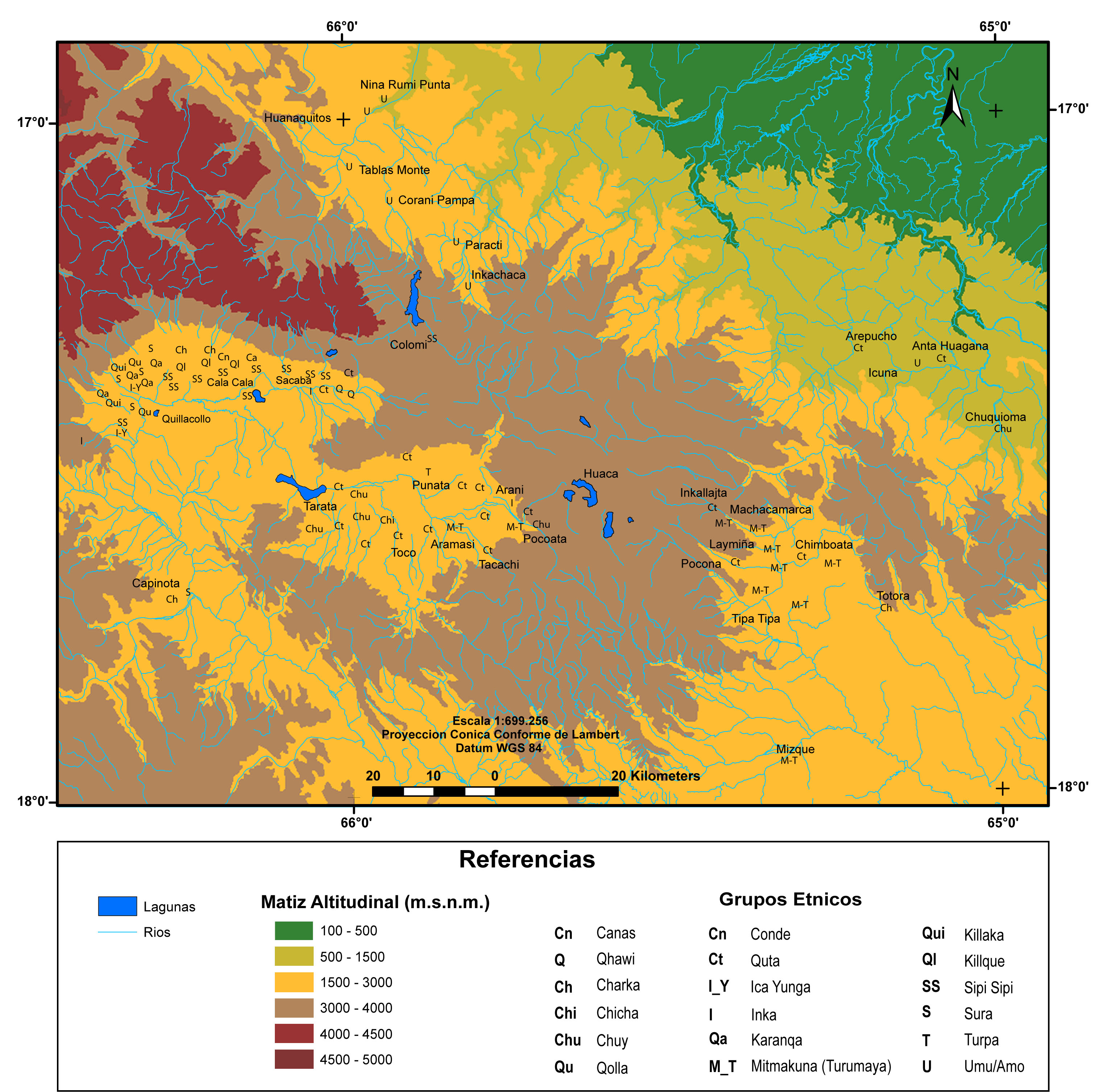

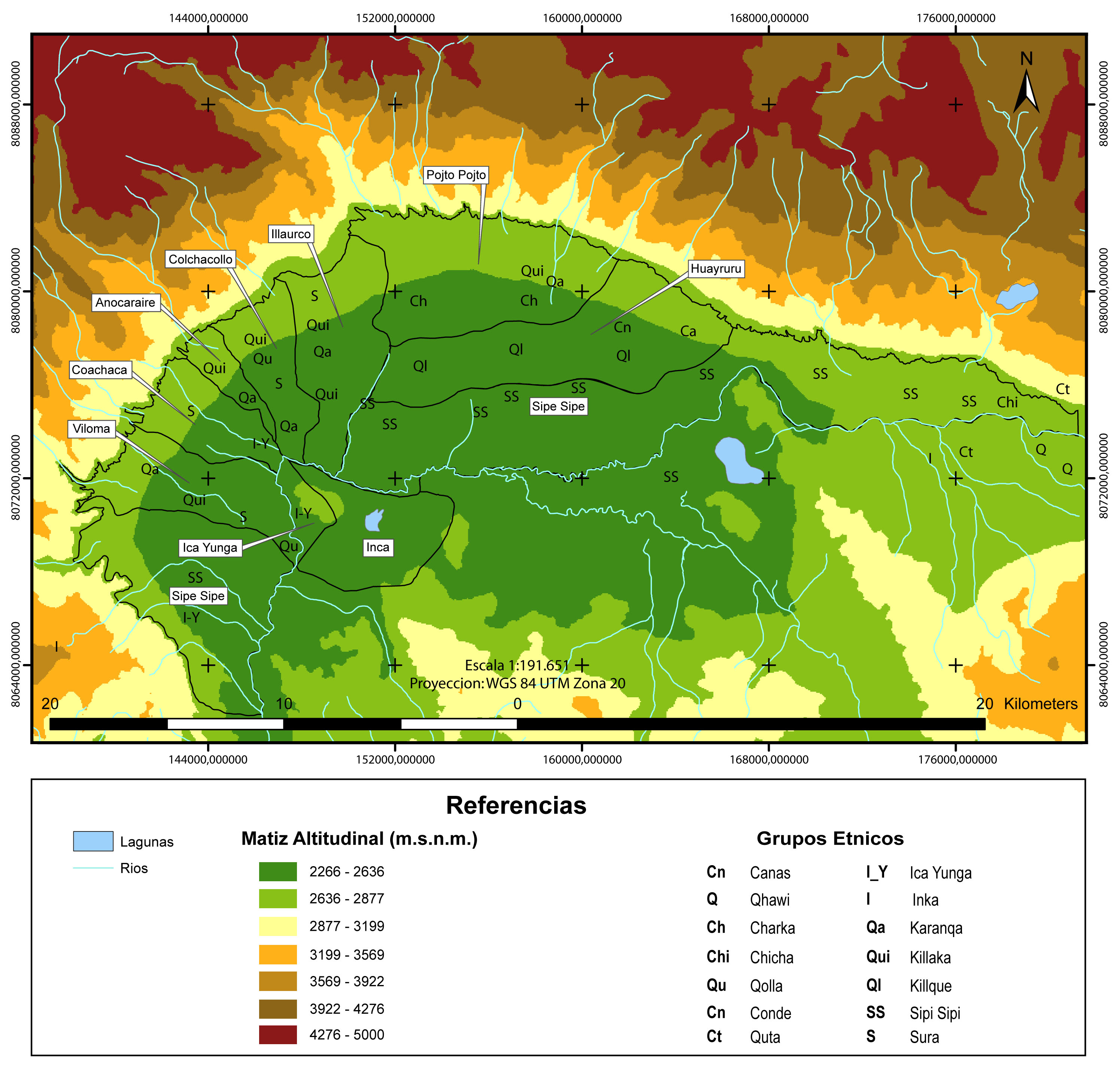

Building on the model of “vertical control of ecological tiers” (see AYMARA POLITIES of THE QULLASUYU in the 16th CENTURY ), the Incas implemented significant resettlement policies to defend their expanding frontiers and increase agricultural production for the state.2 By strategically relocating populations across different ecological zones, the Inca State aimed to optimize resource management and strengthen its control over the territory. Breaking up hostile ethnic groups and rewarding loyal ones with access to new valley lands, the Incas relocated large segments of population to different and sometimes very distant areas, thereby changing the ethnic composition of the conquered territories. Resettled populations, called mitmaqkuna (or mitimaes in Spanish colonial records) formed multi-ethnic colonies (see MULTI-ETHNIC TERRITORY under INCA DIRECT RULE: THE CENTRAL AND UPPER VALLEYS OF COCHABAMBA in the 1530s and MULTI-ETHNIC TERRITORY under INCA DIRECT RULE: THE LOWER VALLEY OF COCHABAMBA in the 1530s ) and retained, in principle, their ethnic ties with their native communities. In practice, however, they were under direct supervision of state officials and administrators. The specific situations varied greatly in the different areas of the state.

In sum, when the Spaniards embarked on their conquest of the Tawantinsuyu in the 1530s, they encountered a rich tapestry of diverse peoples integrated into a complex state society spread across a vast territory. The human landscape the Spaniards found was a result of the organizational structure and population management strategies implemented by the Inca State. During the initial stages of Spanish colonization, the Spanish colonial state would take advantage of some Inca state institutions, co-opting, re-signifying, and redirecting them to very different ends.

REFERENCES:

D’Altroy, Terence. The Incas. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2002.

Larson, Brooke. Colonialism and Agrarian Transformation in Bolivia: Cochabamba 1550–1900. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988.

Murra, John. Formaciones económicas y políticas del mundo andino. Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, 1975.

Nielsen, Axel. “El Tawantinsuyu: Cosmología, economía y organización política.” In Camino ancestral Qhapaq Ñan. Una vía de integración de los Andes en Argentina, edited by Victoria Sosa, 24–52. Buenos Aires: Ministerio de Cultura de la Nación, Secretaría de Patrimonio Cultural, 2020.

Pärssinen, Martti. Tawantinsuyu: The Inca State and Its Political Organization. Helsinki: Suomen Historiallinen Seura, 1992.

Patterson, Thomas. The Inca Empire: Formation and Disintegration of a Pre-capitalist State. New York: Berg Publishers, 1997.

Spalding, Karen. Huarochirí: An Andean Society under Inca and Spanish Rule. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1984.

Stern, Steve. Peru’s Indian Peoples and the Challenge of Spanish Conquest: Huamanga to 1640. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1982.

Terence D’Altroy, The Incas (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2002), 88; Axel Nielsen, “El Tawantinsuyu: Cosmología, economía y organización política,” in Camino ancestral Qhapaq Ñan: Una vía de integración de los Andes en Argentina, ed. Victoria Sosa (Buenos Aires: Ministerio de Cultura de la Nación, Secretaría de Patrimonio Cultural, 2020), 40; Martti Pärsinnen, Tawantinsuyu: The Inca State and Its Political Organization. (Helsinki: Suomen Historiallinen Seura, 1992). ↩︎

John Murra, Formaciones económicas y políticas del mundo andino (Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, 1975). ↩︎