Abstract

This research analyzes the dynamics of the initial contact and the process of translation and hybridization that took place among the Sertão (interior region) groups of the Bahia de Todos los Santos Captaincy and the various settlers, missionaries, and authorities who arrived there in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. This document also aims at addressing the political culture of the Indigenous people who lived in the Jesuit and Franciscan missions, where they practiced resistance and negotiation. The approach is that of the New Indigenous History, oriented towards raising an historical awareness in which the Indigenous people are subjects and not mere victims. The Bahian interior underwent an extensive colonization process, which involved not only conquest, but also various forms of re-occupation. These were diverse and included the granting of “sesmarías” as a land distribution method; the search for cattle as a means of expansion into the interior; the search for gold and precious metals for wealth acquisition; the human capture and slave trade of both “negros de la tierra” as well as people from Guinea; and the insistence on new systems of food production, intended both to ensure self-sufficiency and to secure Indigenous people’s settlement and attachment to the land. The missions were seen as diverse ways of “dominating” the gentiles, occupying territories and securing property. In the new villages, people of different Indigenous ethnicities mixed among each other, even with settlers and missionaries. They learned new cultural and political practices, which they used to negotiate and protect their own interests; to resist, as well as to recreate their traditions and identities.

This work presents an analysis of the contact relations and the translation or hybridization processes taking place among the Indigenous groups of the interior (Sertão) of the Bahia de Todos los Santos Captaincy and the settlers during the second half of the 17th century and the beginning of the 18th century.1

In addition to gaining insight into the complex operation of translation and the organization of symbols, and as a result of the impact and socialization of these diverse cultural agents, this research also aims at addressing the political actions and problematic relationships between the Indigenous peoples settled in the Jesuit and Franciscan missions, and the various colonial agents.

The characters in this study are the Indigenous people of the Sertão das Jacobinas in the second half of the 17th century and early 18th century; subjects who were neither victims nor heroes, but rather individuals placed in a grey zone of uncertainty between those two roles.

By making alliances with Africans, Creoles, Mulattos, Mamluks, Cafuzos; slaves, formerly enslaved people or freed slaves, other Indigenous groups, and even with “white people,” the Indigenous people asserted their autonomy, their rights, and their interests.

In American and Brazilian historiography, the New Indigenous History is the movement in charge of raising political and historical awareness through which Indigenous people may be seen as subjects and not merely as victims. It also seeks to indicate new directions for the investigation of the social and cultural history of “traditional peoples” or subordinate ethnic groups.

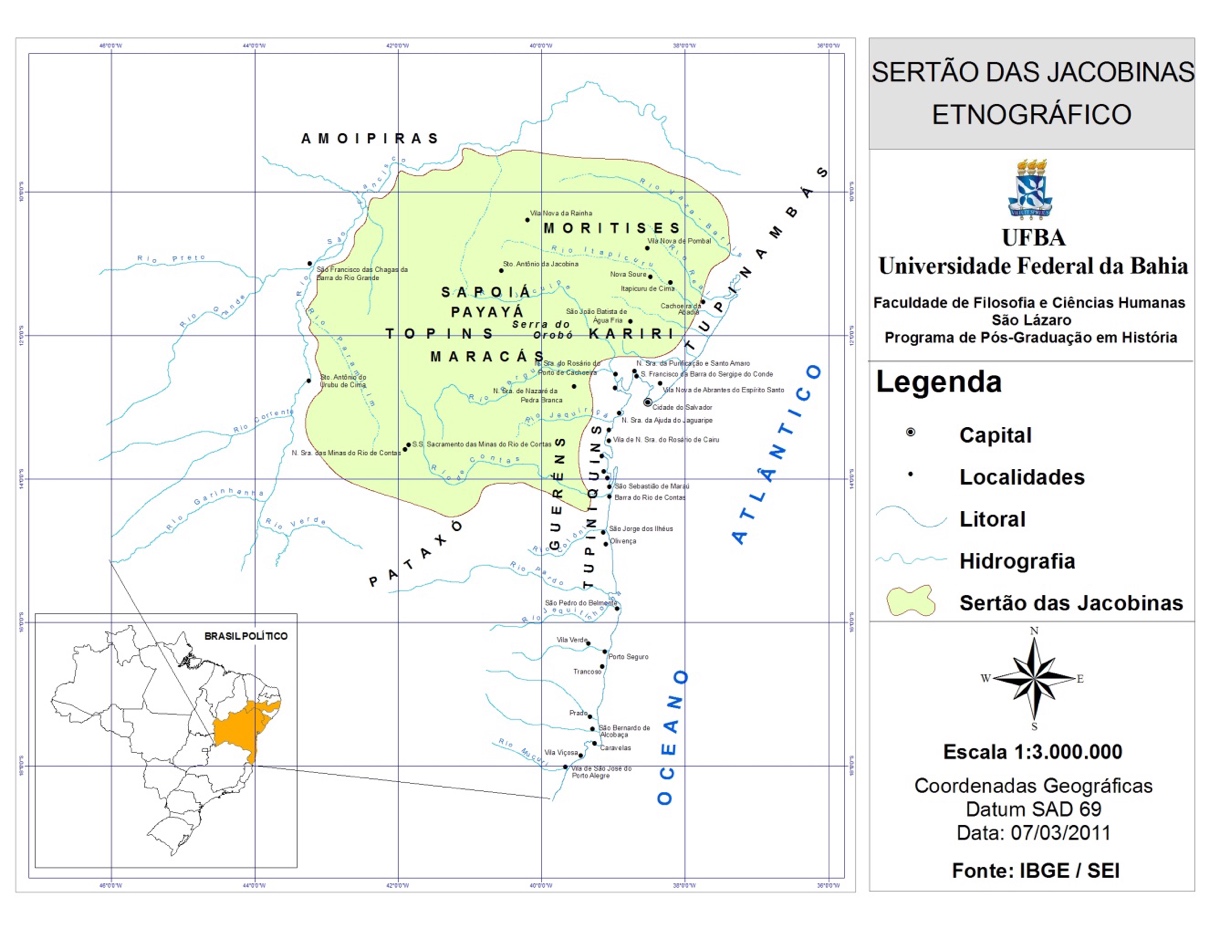

The history of the Indigenous peoples who lived and still live in the interior of Bahia, specifically in the Sertão das Jacobinas region, which currently corresponds to the Chapada** Diamantina and its Piedmont, is a subject matter and a region little studied in historiography and at basic and higher education institutions.

The trajectories of the Indians in the Sertão das Jacobinas —Chapada Diamantina and its Piedmont— are configured as a broken or uneven history, full of gaps, and —in documentary terms—, quite fragmented. The accounts of experiences by various peoples, families and individuals who scattered across or settled in the interior of this vast region are extremely diverse.

In the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, this region was inhabited by Indigenous groups such as the Payayá, the Sapoiá, the Moritises, the Maracás, the Caimbés and the Topins. The Bahia del Sertão region underwent a lengthy process of colonizing conquest and re-occupation.

Ethnographic map of Sertão das Jacobinas. In Santos, Solon Natalicio Araujo dos. “Conquista y Resistencia de los Payayá en el Interior de las Jacobinas: Tapuia, Tupi, colonos y misioneros (1651-1706).” Master´s thesis. Salvador: Graduate Program in History: FFCH-UFBA, 2011. p. 38.

The Indigenous groups integrated into the Portuguese colony became village Indians and went on to play distinct roles in the developing colonial society.

The historiography on the Bahian interior region produced by memorialists, assigns the responsibility over the territorial expansion to powerful regional and local families. However, this version omits the engagement of Indigenous and Black populations.

In the Captaincy of Bahia, as well as in the other regions belonging to the colony, occupation and settlement were based on a series of activities. Namely, the concession of “sesmarías” was applied as a means of land distribution; cattle ranching fostered expansion towards the interior; the search for gold and precious metals was used to obtain wealth along with “negros de la tierra” and Guinea people for forced labor. In turn, food production mechanisms aimed at securing self-sufficiency and breeding a sense of belonging and attachment to the territory. Through the operation of the missions, they saw a way of “dominating” the gentiles, by occupying and securing possessions.

Along the conquest and occupation processes of the Sertão of Bahia, in the second half of the 17th century and early 18th century, wars and alliances with various Indigenous peoples were waged and created, and cattle ranches were established with African, Creole and mestizo servants and slaves along the large and medium-sized rivers and their tributaries. The early settlers of the Sertão region were not the landowners —sesmarías—, but their slaves and serfs. Faced with a difficult life in the interior, the settlers had to adopt leather utensils, Aboriginal customs, and Indigenous food.

The cultural, geographic, and economic spaces of the Bahian Sertão region stand out as structures resulting from the complex interactions of conflicts and negotiations between various Indigenous groups, enslaved and freed Africans, Creoles and mestizos, different religious orders, different and powerful landowners, Bahian and São Paulo “sertanistas” and colonial authorities. This study shows that Luso-Brazilian colonization advanced according to the possibilities offered by the alliances with the Indigenous people, their capacity to react, and the interests of the various colonial agents.

The “Barbarians War” in the Recôncavo and Sertão das Jacobinas regions, rather than an Indigenous extermination for the expansion of the colonial project towards the interior, was a complex web of cultural and power relations between the colonial agents and the Indigenous peoples called “Tapuias.” The historical role of the Payayá group in these conflicts —far from being that of silent and passive victims—, was that of subjects who, under certain circumstances, fought, deceived, and allied themselves with the Portuguese-Brazilian colonists, following their own interests and possibilities of survival.

After the Barbarian War in the Sertão das Jacobinas region, the dispersal possibilities of the various Indigenous groups were “escaping to the bush” and joining the missionary villages —Jesuits, Franciscans, Capuchins, Carmelites—, either under the crown´s management or privately managed.

Church of the Bom Jesus da Glória Mission in Jacobina, Bahia, Brazil, 2006. Photograph by Alex Felix, courtesy of Valter Oliveira.

The process of colonial construction in the Sertão of Bahia was extensive and conditioned by the occupation, the private and communal use of the land, the establishment of ranches and the expansion of cattle-raising, the extraction of saltpeter and gold, the work of missionaries, and the foundation of districts, parishes, cities, and counties.

The exploitation of labor in the gold and saltpeter mines and cattle ranching, together with the resulting demographic decline in the villages, triggered various confrontations between Indigenous people, missionaries, settlers, and authorities.

Within the settlements, the various Indigenous ethnic groups mixed among each other, but also with settlers and missionaries, and learned new cultural and political practices that allowed them to negotiate while protecting their own interests.

As a space for social interaction and Indigenous resistance, the villages provided the Indigenous people with the opportunity to adapt to the Colony, recreating their traditions and identities. The presence of elements borrowed from Christianity in Indigenous sacred narratives and rituals reveals shared translations between Indigenous groups and missionaries. The settled Indians learned to negotiate within the terms of colonial society and became agents of fundamental recognition and rights vindication, thus recreating their identities.

The documentation herein analyzed reveals the translation and mediation process through which the Indigenous peoples and missionaries projected their respective images and symbolic universes. It additionally highlighted how the Indigenous groups, in their condition of villagers, came to constitute a generic social category imposed by the colonizers, although appropriated by them and created through the process of their interaction and historical experience with the different social agents in the Colony.

Finally, with a wealth of information, sources, references, and recent productions of knowledge that depict the Indigenous peoples as agents and protagonists of the historical process of re-occupation and settlement of the Sertão of Bahia, we intend to point out the possibilities of research and teaching of the histories of indigenous peoples in Basic and Higher Education in this vast region in the interior of Bahia.

Bibliography:

Bahia, Governo do Estado da. SEI - Superintendência de Estudos Econômicos e Sociais da Bahia. 2001. Evolução territorial e administrativa do Estado da Bahia: um breve histórico. Salvador: SEI.

Cunha, Manuela (org). 1992. História do Índio no Brasil. 2 ed. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras.

Dantas, Beatriz G., Sampaio, José A. L., Carvalho, Maria Rosário G. de. 1992.

“Os povos indígenas no Nordeste brasileiro: um esboço histórico”. In: Cunha, Manuela C. História dos índios no Brasil. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras.

Monteiro, John. 2001. “Tupis, Tapuias e Historiadores. Estudos de História Indígena e do Indigenismo.” Tese de Livre Docência. Campinas: Unicamp.

Ott, Carlos. 1993. As culturas pré-históricas da Bahia: a cultura material. Salvador: Bigraf.

Ott, Carlos. 1944. “Os elementos culturais da pescaria baiana.” In: Boletim do Museu Nacional. Nº 4. Rio de Janeiro, October 30.

Ott, Carlos. 1958. Pré-História da Bahia*.* Bahia: Publicações da Universidade da Bahia.

Paraiso, Maria Hilda Baqueiro. 1985. Os Kiriri Sapuyá de Pedra Branca. Salvador: UFBA.

Perrone-Moisés, Beatriz. 1992. “Índios livres e índios escravos: Os princípios da legislação indigenista do período colonial (séculos XVI a XVIII)”, in: Cunha, Manuela Carneiro da (org.). História dos Índios no Brasil. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras.

Pompa, Cristina. 2003. Religião como tradução: missionários, Tupi e Tapuia no Brasil colonial. Bauru: EDUSC/ANPOCS.

Puntoni, Pedro. 2002. A Guerra dos Bárbaros: povos indígenas e a colonização do sertão. Nordeste do Brasil, 1650-1720. São Paulo: Hucitec-EDUSP; FAPESP.

Reis, João José & Silva, Eduardo. 1989. Negociação e Conflito: a resistência negra no Brasil Escravista. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras.

Santos, Solon N. A. dos. 2011. “Conquista e Resistência dos Payayá no Sertão das Jacobinas: tapuia, tupi, colonos e missionários (1651-1706).” Disertación de Maestría. Salvador: Programa de Posgrado en Historia. FFCH-UFBA.

* Translator’s note: The Sertão is a Brazilian semi-arid geographical region in the northeast of the country with its own environmental and socio-cultural characteristics.

** Translator’s note: The Chapada is an elevated rock formation with a flat portion at the top.

With special thanks to my advisor, Dr. Maria Hilda Baqueiro Paraíso, to Dr. Ann Farnsworth-Alvear, to the Penn-Mellon Just Futures Initiative “Dispossessions in the Americas” for supporting my participation in the Ethnohistory Workshop at the University of Pennsylvania (UPenn), Philadelphia, United States, and to FAPESB for supporting the research under the project Escravidão, sociedade e economia na vila de Jacobina (séculos XVIII e XIX) , coordinated by Dr. Jackson Ferreira. ↩︎